2022 Volume 63 Issue 6 Pages 923-930

2022 Volume 63 Issue 6 Pages 923-930

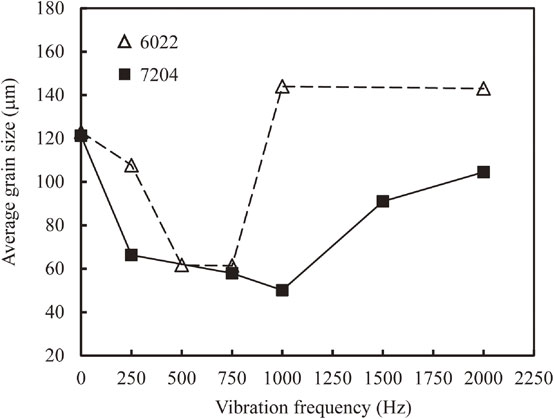

In the present study, we solidified JIS A7204 and A6022 (7204 and 6022 in short hereafter) aluminum alloys using an electromagnetic vibration (EMV) technique as a function of vibration frequency. The solidified structures were qualitatively observed, and then average grain size was quantitatively measured using the Image-Pro Plus® software by a centroid method. Similarly to our previous observations of other alloy systems, the average grain size versus vibration frequency in both alloys exhibits a “V-shaped” relation; it reaches minimum of approximately 50 µm at the frequency of f = 1000 Hz in 7204 alloys and around 61 µm from the frequency of f = 500 Hz to f = 750 Hz in 6022 alloys. The microstructure formation was discussed when considering the substantial difference in electrical resistivity between the primary aluminum solid solution and the remaining liquid, which resulted in an uncoupled movement between the primary mobile solid and remaining sluggish liquid. Possible influences of different solute elements on solidification structures were briefly presented.

Aluminum alloys are an important class of light-weight alloys and have been widely applied in industries. By adding different solute elements, aluminum alloys can be fabricated with increased mechanical and/or chemical properties. The 7204 aluminum alloy is doped by the primary solute of zinc and magnesium and then some little amounts of copper and chromium metals. When silicon and magnesium are added as main strengthening elements into aluminum melts, good workability and corrosion resistance can be achieved. The 6022 alloy belongs to this group of commercial alloys. Because of the superior mechanical and corrosion resistance properties, these two alloys, i.e., 7204 and 6022, have been widely utilized in automotive, marine, and aviation applications.

As presented above, the addition of solute elements can improve properties of aluminum alloys because of various strengthening mechanisms. In the meanwhile, these elements are subjected to redistribution in the solid/liquid interface during solidification and thus forming a solute-redistribution boundary zone. Under a usual casting state with a positive temperature gradient, a constitutional undercooling can be readily produced within the zone, and thus the crystal growth interface destabilizes to form coarse dendrites in a continuous cast billet, which can deteriorate properties of aluminum alloys.

The Hall-Petch equation gives the relation of grain size as a function of tensile strength; the finer the grains are, the higher the properties will be yielded for alloys in usual foundry engineering. For aluminum alloys, deformability is also a great concern. It has been clarified that an alloy with a grain-refined structure can be processed with large deformation prior to the appearance of cracks. Therefore, to cast an aluminum alloy billet with a refined structure without substantial change of amount and/or species of solute elements is an important subject for aluminum industry.

Principally, there are two types of techniques, by which the refinement of aluminum alloys can be achieved. One is to impose a certain external energy that can promote the segmentation of dendrites into fine debris. The external energy source can be mechanical,1–3) electromagnetic,4–6) or ultrasonic,7–10) i.e., mechanical stirring or vibration, electromagnetic stirring or ultrasonic vibration. In these methods, a stirrer, vibrator, or horn is used to transfer external energy to the crystallizing alloys and thereby yield refined structures. Contamination from the stirrer or the horn is unavoidable because aluminum melts are aggressive and can react with most refractory materials, by which some undesired phases may be produced. Moreover, the intensity of the externally imposed energy may be attenuated during propagation within the melt and thus yields an inhomogeneous structure within the volume of the alloy. It is noted that in electromagnetic stirring, although the electromagnetic force drives the melt to move without a tangible stirrer, there was a report11) that there is some inhomogeneity in solidified structures, and macro segregation in composition distribution has been verified.

The other is to incubate aluminum alloys with some reagent alloys to generate more heterogenous nucleation sites and thus produce a refined solidification structure. It is well known that reagent alloys, e.g., Al–Ti–B alloys,12–14) always contain rare metals of titanium and boron that are biasedly deposited in certain areas. Therefore, it is of some risk when aluminum alloys production is heavily relied upon these rare metals as a stable supply chain is always a concern. The addition of incubation reagent alloys may complicate the recycling process of used aluminum products and thus increase the recycling cost. For more information on refinement of the alloy system using the incubation method, one can refer to two excellent reviews by Eston and StJohn14) and Murty et al.15)

The electromagnetic vibration (EMV) technique is based on Fleming’s left-hand rule, i.e., the working principle of a motor. For a conductor in a static magnetic field, when the electric current flows through the conductor perpendicularly to the direction of the magnetic field, the conductor is driven to move according to Fleming’s left-hand rule. When the electric current is alternating current (AC), the conductor is driven to move periodically centering its initial equilibrium position, i.e., EMV can be generated.

In comparison with mechanical stirring or ultrasonic vibration, by which a stirrer or a horn is used, in the EMV technique, the alloy is driven to move by the electromagnetic force, and thus no contamination can be involved, which is similar to the electromagnetic stirring. Moreover, there is no decrease for AC during flowing through the conductor, therefore, no attenuation can be inferred to occur within the sample and thus it is expected to achieve a uniform solidification structure throughout the entire volume of the sample. This differs from the electromagnetic stirring to yield inhomogeneous structures and compositional macrosegregation.

The earliest work using the EMV technique to refine solidification structures may be attributed to Vives,16–18) who ascribed the refinement mechanism of Al alloys to electromagnetic pressure. From then on, researchers have improved and modified the technique to apply to various metals19,20) and alloys.21–23) Cui and co-workers24) employed the technique to solidify metallic billets at low vibration frequencies. Zhong et al.25) combined the technique with semi-continuous casting to solidify Al–Sn alloys with a refined structure. Du and Iwai26) employed the weak EMV to refine Mg2Si crystals. Very recently, a special issue on physical phenomena under the imposition of EMV was published, in which Iwai27) summarized his group’s investigation from different aspects. In the early work of Miwa and co-workers,19–23) they claimed that a so-called micro-explosion mechanism was responsible for the structure refinement during the imposition of EMV. In recent years, this has been updated28) when considering the electrical resistivity of primary solid and liquid in the mushy zone during EMV processing.

In the present study, we used the EMV technique to solidify 7204 (the main chemical composition is Al–3.96 mass% Zn–0.84 mass% Mg) and 6022 (the main chemical composition is Al–1.14 mass% Si–0.56 mass% Mg) alloys under various frequencies. The microstructures were observed, and the average grain size was characterized, revealing that EMV was universally effective in refining the solidification structures within a specific frequency range. The refinement mechanism was discussed when considering the electrical properties of the primary solid and remaining liquid. A minute difference in refined structures in 7204 and 6022 alloys was discussed when considering the role solutes in these two alloys. Future work on the topic was briefly outlined, which was useful in furthering the understanding of structure refinement in foundry engineering of aluminum alloys.

In the present study, a superconducting magnet was used to produce a static magnetic field with the magnetic flux up to 10 T within the magnet chamber. The aluminum alloy specimen was machined into a rod with the nominal diameter of 6 mm and 80 mm in length. The rod was then encapsulated into an alumina tube with the same nominal diameter. A blind hole was made in the alumina tube, in which a K-type thermocouple was imbedded to monitor the temperature of the specimen during processing. The setting kit was fixed to a specimen holder and then two Cu electrodes were connected to the two extremes of the specimen for AC flow. Figure 1(a) showed the front-view schematic of the present setting kit.

(a) A front view schematic to show the experimental setting kit. (b) The temperature distribution along the longitudinal direction of the tube captured by 5 thermocouples at 700°C and 750°C, respectively. (c) A representative temperature profile acquired by the K-type thermocouple in (a), showing the timing for the EMV imposition. (d) A sectioning plane to indicate the region for structure observation after the specimen was solidified.

Here it worth noting that in most of our previous experiments,28,29) the specimen was as short as 50 mm, which was sandwiched by two carbon blocks and then connected to the Cu electrodes. This kind of soft contact, for one aspect, may result in experimental failure, and for the other aspect, may produce some contamination because of the chemical reaction between carbon and metallic melts. In our recent optimization of solidification structures and magnetic properties of a semisolid slurry,30) we found that the carbon electrode can react with Nd–Cu eutectic and thus produce undesired phases that may deteriorate magnetic properties. In aluminum alloy foundry engineering, although the carbon crucible has been widely used, it was reported31) that graphite may reaction with aluminum melt to form a minute amount of Al4C3 that may influence solidification behavior of the alloy. Hence, in the present experiment, a specimen with sufficient length of 80 mm was used, as depicted in Fig. 1(a).

A movable arc-shaped carbon heater with a length of 40 mm was used to heat the specimen by covering the alumina tube. When the specimen was heated, only the central region of the specimen could be melted at the present target temperature because of the uniform temperature distribution in the central region of approximately 20 mm in length, beyond which there is a relatively large temperature gradient, as indicated in Fig. 1(b) that was acquired using five thermocouples in different locations at two temperatures. As the specimen is much longer than the carbon heater, it leaves two extremes of the specimen unmelted and thus avoids the contamination from foreign impurities from the sandwiching electrodes. In this case, only the central region was observed and characterized.

From the working principle of EMV, one can become aware that at least, three variables are involved for the production of the Lorentz force, F, i.e., the magnetic field intensity, B0, the AC value, J, and the corresponding AC frequency, f. One can find that F = B0 × J, showing that B0 is linear to F when J is kept as a constant and vice versa. This indicates that the higher the value of B0 or J is, the larger the force of F will be produced when J or B0 is a constant. The present authors verified that there was almost a linear influence of B0 and J on the structure formation in AZ91D32) and AZ3133) magnesium alloys, which showed good consistency with theoretical prediction, i.e., the larger the force F was imposed, the finer the grains could be obtained except for a higher J beyond 120 A that produced a great amount of Joule heat and thus coarsened the solidification structure. Hence, in the present study, we kept B0 = 10 T and J = 60 A and then probed the influence of the frequency AC, i.e., vibration frequency, f, on solidification structures of 7204 and 6022 alloys. It is noted that the voltage imposed upon the specimen ranged approximately 4.5 to 6.5 V during EMV processing with a minute variation because of the soft contact between the specimen and the carbon electrodes.

The detailed experimental procedure was as follows: after the specimen kit was horizontally mounted into the magnet bore, the arc-shaped carbon heater was covered onto the alumina tube. The specimen was heated, melted, overheated, and then kept at 750°C for 120 seconds to homogenize the central region. Here, it is supplemented that from Fig. 1, one can see that when the heating power was switched on, the carbon heater became hot first and then the alumina tube was heated and finally the specimen in the ceramic tube was heated by thermal conduction. As the ceramic tube is poor in thermal conductivity, it takes time to reach thermal equilibrium, i.e., there is a temperature lag between the thermocouple digit and the actual temperature of the specimen. This is why the specimen was held for 120 s to homogenize the central region. The heating power was turned off and at the same time, the carbon heater was pulled up to cool the sample naturally. When the specimen temperature reached 700°C, the power of AC was switched on, and thus EMV was imposed upon the specimen. When it was cooled to 580°C, the power of AC was turned off and EMV was terminated. To guarantee all samples comparable, the heating and cooling process for all specimens were the same except that the vibration frequency was different. A representative temperature profile was illustrated in Fig. 1(c), showing the EMV imposition timing in the present study.

Here, it is supplemented that a differential thermal analysis (DTA) apparatus was used to determine the solidus and liquidus of the 7204 and 6022 alloy. Figure 2 depicts a presentative DTA profile of the 6022 alloy, showing the onset and endset crystallization temperatures of the alloy when cooled at a rate of 5 K min−1. As the aluminum alloy was set in an alumina crucible that is an excellent reagent to activate heterogenous nucleation, there is a negligible melt undercooling, and thus the onset and endset temperatures of crystallization can be regarded as the liquids and solidus, respectively. For the 7204 alloy, the liquidus and solidus are 648°C and 590°C, respectively and for the 6022 alloy, they are 650°C and 587°C, respectively.

A differential thermal analysis (DTA) profile showing the onset and endset temperatures of the 6022 alloy when it was cooled at a rate of 5 K min−1 from 700°C.

According to our previous experience, effective refinement of the primary phase occurs when EMV is imposed around liquidus, i.e., from a temperature above liquidus and then into the semisolid mushy zone. The imposition of EMV above liquidus only, i.e., prior to the formation of a primary solid phase, or far below the liquidus with a great amount of fraction solid cannot produce refinement, as we have demonstrated in AZ91D magnesium alloys.34) This is why the imposition in the present study commenced from 700°C and then through the semisolid region. This operation could guarantee that the present EMV was imposed effectively in refining solidification structures.

After the specimen was crystallized, it was cut along the diametric direction and then mounted, ground, and polished following the traditional metallographic preparation approach. Because of a uniform temperature distribution in the central region, as mentioned above, only microstructures in this region were characterized, as depicted in Fig. 1(d). To reveal the solidification structure with individual grains, a Barker’s reagent was used to etch the specimen and then structures were qualitatively observed under an optical microscope (OM) using polarized light to show contrast.

To quantitatively characterize the grain size of specimens solidified at various vibration frequencies, the average grain size of OM structures was measured by an Image-Pro Plus® software. The detailed method was as follows: the outline of a grain was first delineated and then the simple closed curve was analyzed to find the centroid of the grain. The grain size could be obtained by calculating the mean length of lines passing through the centroid at an interval of every two degrees, as schematically depicted in Fig. 3. In comparison with the traditional line intercept technique, the present method is more objective and can avoid arbitrary selection that may give rise to the desired data.

(a) A structure captured in a polarized light microscope to show the contrast of grains. The outline of a separate grain is closed by a red curve. (b) The closed curve is cut out and the average length of diameters is measured at 2-degree intervals when passing through the centroid of the grain.

To reveal the impact of EMV on the structure change, the 7204 alloy was first solidified without the imposition of EMV at the same cooling condition as those with EMV. Figure 4(a) shows the OM structure of the alloy solidified under this condition. For simplicity, it is denoted as f = 0 Hz, hereafter. It is evident that coarse grains and developed dendrites can be verified, which are typical in a usual casting in foundry engineering. Here, it is noted that in comparison with binary Al–Si alloys, the 7204 alloy includes more kinds of solute elements except for the primary zinc and magnesium, i.e., the solute is multiple. It has been demonstrated that different alloying elements in aluminum alloys have different segregating powers and thus influence the growth restriction factor that is important in grain refinement. Here, the concept of segregating power needs to be explained, which is essential in elucidating the segregation behavior of elements upon solidification according to Easton and StJohn.14) Segregating power reflects the growth-restricting effect of solute elements on the growth of the solid-liquid interface of new grains when they grow into a melt. This can be defined as m · c0(k − 1), where m is the gradient of the liquidus, c0 is the concentration of the solute in the alloy and k is the distribution coefficient between the equilibrium concentrations of the solid and liquid at the growing interface. When several solutes are added into a melt, it is simply assumed that there is no interaction between these solute phases. Consequently, a linear superposition relation applies as ∑mi · c0i(ki – 1).14) For the present 7204 and 6022 alloy, in addition to the major solute elements mentioned above, there are some other minor solute elements, e.g., 0.43 mass% Mn and 0.15 mass% Cr in the 7204 alloy and 0.1 mass% Fe and 0.06 mass% Mn in the 6022 alloy. These solute elements may improve segregating power, which may be applied to account for the relatively smaller grains in the as-cast 7204 and 6022 alloy compared with coarse ones in Al–Si alloys, where they are usually in a millimeter scale.35)

Polarized light microstructures of 7204 alloys solidified at the frequency of (a) 0 Hz, (b) 250 Hz, (c) 750 Hz, (d) 1000 Hz, (e) 1500 Hz, and (f) 2000 Hz, respectively when the EMV was imposed at B0 = 10 T and J = 60 A.

When EMV is imposed from f = 250 Hz to f = 1000 Hz, the solidification structures become refined with equiaxed grains in comparison with that at f = 0 Hz, as depicted through Figs. 4(b) to 4(d). A careful observation reveals that the structure in Fig. 4(d) is the finest among these structures. In contrast, when the frequency increase to f = 1500 Hz and f = 2000 Hz, the structures become coarse, similarly to that observed at f = 0 Hz.

For the 6022 alloy, Fig. 5 shows the structure evolution as a function of vibration frequency. The overall structure development exhibits a similar tendency to that of 7204 alloys. A minute difference is that the frequency range in which a refined structure can be produced becomes narrow, i.e., refined equiaxed grains can be produced only from f = 500 Hz to f = 750 Hz, beyond which coarse dendrites can be observed. This difference may be attributed to the different segregating powers of the solute elements contained in 7204 and 6022 alloys, i.e., Zn may tend to be more powerful in segregation and thus yield a refined structure. The other indirect evidence is that less secondary dendrites arms can be discerned in 7204 alloys solidified at f = 0 Hz and f = 2000 Hz in Figs. 4(a) and 4(f). In contrast, well-developed secondary dendrite arms can be seen in 6022 alloys solidified at the same frequencies, as revealed in Figs. 5(a) and 5(f). This may attribute to a stronger impact in growth-restriction effect of zinc than that of silicon.

Polarized light microstructures of 6022 alloys solidified at the frequency of (a) 0 Hz, (b) 250 Hz, (c) 500 Hz, (d) 750 Hz, (e) 1000 Hz, and (f) 2000 Hz, respectively when the EMV was imposed at B0 = 10 T and J = 60 A.

Figure 6 depicts the quantitative average grain size of both alloys as a function of vibration frequency. At f = 0 Hz, two alloys have almost the same average grain size, being of approximately 120 µm. When EMV is imposed, the average grain size decreases first and eventually increases when the frequency exceeds a critical value. This is consistent with the qualitative observation, i.e., both profiles exhibit a “V-shaped” pattern, similarly to those of aluminum alloys21,36) and magnesium alloys.28,37) More specifically, the average grain size of the 7204 alloy can be as fine as approximately 50 µm at f = 1000 Hz, while for the 6022 alloy, the smallest average grain size is ca. 61 µm in the range of f = 500 Hz to f = 750 Hz. Here, it is worth supplementing that a representative structure in each specimen was captured, outlined, and then measured, by which reliable data can be acquired.

Measured average grain size of 7204 and 6022 alloys as a function of vibration frequency.

As far as the influence of an externally imposed energy source on structure formation during solidification is concerned, an intuition is that the higher energy is imposed, the finer the structure can be achieved because the higher energy can promote the dendritic fragmentation from weak necking areas and thus multiply dendrite debris. This has been verified in mechanical1,2) and ultrasonic8–10) vibrations by different research groups. The present authors also confirmed that when vibration frequency and AC are kept as constants in EMV processing, the larger the magnetic flux intensity is imposed, the finer the solidification structures can be observed in AZ3133) and AZ91D32) magnesium alloys because of the increased Lorentz force, which drives the semisolid slurry to move at a faster velocity with higher kinetic energy.

However, in the present study, both the magnetic flux intensity B0 and the value of AC are kept constant, which produces the same Lorentz force upon the specimen in each experimental run and is independent of vibration frequency. Therefore, the refinement should be originated owing to some new mechanism that is strongly dependent on vibration frequency. Here, it is worth noting that in the early work on EMV, the occurrence of structure refinement was attributed to cavitation, e.g., Vives16–18) believed that cavitation was responsible for refinement when the electromagnetic pressure exceeded a critical value and Miwa and co-workers19–23) termed the phenomenon “micro-explosion” in their early literature. It has been verified that cavitation indeed occurs in metallic liquids10,38) when ultrasonic vibration is imposed, which can yield grain refinement in solidified ingots. However, the refinement in EMV processing always occurs in a frequency range from several hundreds to one thousand Hz, as verified in this study, which is far less than the ultrasonic frequency greater than 20000 Hz. On the contrary, developed primary aluminum dendrites without refinement were confirmed in the Al–7% Si alloy39) when the EMV frequency was 10000 Hz that is near to the ultrasonic band.

After realizing this discrepancy, we28) proposed a novel mechanism by considering the substantial difference in electrical resistivity between the primary magnesium solid and the surrounding liquid in the AZ31 alloy when it was solidified at various vibration frequencies. The principal concept is that, after the primary Mg solid crystallizes and coexists with remaining liquid in the mushy zone, they are respective resistors in a parallel circuit when AC flows through the semisolid region. Therefore, the mushy zone is simplified to be two resistors in the parallel circuit.

The most important is that these two resistors, i.e., the primary solid and the remaining liquid, have different electrical resistivities. A representative case is that the electrical resistivity of the pure Mg solid at the melting point of 650°C is 153.5 nΩ·m, and it is 274.0 nΩ·m for the counterpart liquid at the same temperature.40) Similarly, it is 114.7 nΩ·m for the pure Al solid at the melting point of 660°C, and it is 227.2 nΩ·m for the liquid Al at the same temperature.41) This indicates that at the same high temperature, the electrical resistivity of the solid, ρ(s) is approximately half of that of the liquid, ρ(l), i.e., ρ(s) ≅ (1/2)ρ(l). Although the solute elements may have a certain influence on resistivities when they are doped into the pure substance, the overall quotient cannot be varied as they are less than several percentages. For instance, AZ31 is primarily magnesium-based and Al–7 mass% Si is aluminum-based. The amount of aluminum in the present 7204 is more than 90% and that in 6022 is more than 95%. Hence, the conclusion on the electrical resistivity for the primary aluminum solid solution and remaining liquid should be applicable to these two alloys as well.

Assume that a unit volume of solid Al and that of liquid Al are two resistors in the parallel circuit, the amount of AC passing through the solid is approximately twice of that through the liquid as ρ(s) ≅ (1/2)ρ(l). The Lorentz force produced upon the solid, F(s), will be twice of that upon the liquid, F(l), i.e., F(s) ≅ 2F(l). For the aluminum solid and liquid at the melting point, there is a negligible difference in density,41) i.e., it is 2.5 g cm−3 for solid and 2.4 g cm−3 for liquid. This will drive the aluminum solid to move with a doubled acceleration to that the surrounding liquid. From the deduction presented above, one can readily find that when EMV is imposed, the primary aluminum solid phase is mobile with a higher acceleration to cover a longer distance in comparison with the sluggish liquid, which will generate an uncoupled movement between the solid and the liquid.

The present authors28) have quantitatively correlated this uncoupled movement behavior, i.e., the distance covered by the solid within a half vibration cycle in AZ31 alloys after making several assumptions. This should be applicable to the present 7204 and 6022 aluminum alloys as the primary aluminum solid solution phase shares the same characteristics as those of the primary magnesium solid solution. To avoid massive repetition, we skip the detailed deduction and apply the conclusion as follows:

| \begin{equation} s_{(\text{i})} = \text{k}\cdot F_{(\text{i})}/(4f)^{2} \end{equation} | (1) |

Calculated movement distance of the primary aluminum solid, the remaining liquid, and the leading distance covered by the mobile solid, assuming that the electrical resistivities of the solid and liquid can be approximated to be equal to their pure counterparts.

In the present study, the aluminum solid and the surrounding aluminum liquid cannot move synchronically. At the frequency range in which refinement can be achieved, more specifically, from 500 Hz to 1000 Hz, Δs decreases approximately from 800 µm to 200 µm. This leading distance is sufficient for the mobile aluminum solid to break through the solute redistribution boundary layer that is usually in hundreds of micrometers in usual solidification.42) In this case, no stable solute layer can be established ahead of the growing interface, and thus little compositional undercooling can be inferred to occur, which makes the growing interface destabilize to form dendrites. When the vibration frequency increases, the leading distance decreases, e.g., at f = 2000 Hz, Δs decreases to less than 50 µm. In this case, the mobile solid may have some disturbance to the solute distribution layer, while the movement is, at all, within the scope of the boundary layer. This may be why the solidification structure is coarse when the vibration frequency is further increased.

After clarifying the structure formation at the medium and high frequencies, we should consider the reason that a relative coarse structure is formed at low frequencies. From Fig. 7, it is evident that the leading distance becomes long, e.g., the leading solid spans approximately 40 mm at f = 50 Hz. Here, we consider an extreme condition that a solid particle is driven to move across the diameter direction from one side to the other, i.e., L = 6 mm, hence, the theoretical time duration for movement is t = 6/(40 × 2f) = 0.0015 s within a half cycle. The half cycle is 0.01 s at f = 50 Hz. This indicates that to cover the distance, only 15% of the half cycle interval is sufficient. In the actual solidification condition, the primary solid phase may disperse uniformly and the time for solid phase displacement is much shorter than that estimated theoretically. Because the sample is encapsulated in the container, the solid particle is blocked around the tube wall and kept being dormant for nearly 85% duration time within a half cycle. In other words, at low vibration frequencies, the total moving time for a solid particle is rather short while the dormant time is quite long. In this case, at a given vibration time, e.g., 20 s, the vibration counts are limited, indicating that the overall vibration efficiency is poor. This will result in incomplete fragmentation and thus yield a coarse structure in comparison with that formed at a medium frequency range.

It is worth supplementing that in Fig. 7, two curves of s(l) and Δs seem to overlap. In calculation, we used the accurate value of 114.7 nΩ·m and 227.2 nΩ·m for solid and liquid phases,41) respectively, which results in a minute difference. For example, at f = 500 Hz, Δs = 782.05 µm and s(l) = 791.76 µm; at f = 1500 Hz, Δs = 86.89 µm and s(l) = 87.97 µm; at f = 2500 Hz, Δs = 31.28 µm and s(l) = 31.67 µm. This enables two curves to locate quite near and makes it hard to distinguish when considering the scale of Y-axis of distance.

Here, it should be noted that 7204 and 6022 aluminum alloys contain various solute elements which have different segregating powers and thus yield different growth restriction factors that are a measure of the growth-restricting effect of solute elements on the formation of a new grain.14) However, we have to admit that up to date, there have been very few quantitative studies on the interaction between moving fields and interface morphologies, and there is no quantitative model for describing a growing dendrite front that includes aspects of dendrite fragmentation, solute transport, dissolution, and crystal growth in the presence of fluid flow, owing to the complexity of the free boundary issue.43) This makes the present analysis semi-quantitative. Further work to develop a quantitative model will enable the discussion to be more quantitative.

Finally, it is supplemented that except for the production of refined structures, the imposition of EMV at the medium frequency range, i.e., from several hundreds to around one thousand hertz, also activates turbulent fluid flow that can promote grain multiplication. Meanwhile, the fluid flow stream can rotate or transfer crystals suspending freely in the remaining liquid, which makes the crystallographic orientations random when observed from a given sectioning plane. This is why a sharp contrast can be found in polarized OM images, as depicted in Figs. 4 and 5.

In the present study, we solidified 7204 and 6022 aluminum alloys when EMV was imposed at different vibration frequencies. The solidified structures of two commercial alloys were observed and the average grain size was measured. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

The authors are grateful to Dr. Y. Mizutani for measuring the temperature gradient profile presented in Fig. 1. Thanks are also due to the Japan Foundry Engineering Society and JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 20K05186) for financial support.