2023 Volume 64 Issue 7 Pages 1387-1400

2023 Volume 64 Issue 7 Pages 1387-1400

Solid-state hydrogen storage in various metal hydrides is among the most promising and clean way of storing energy, however, some problems, such as sluggish kinetics and high dehydrogenation temperature should be dealt with. In the present paper the advances of severe plastic deformation on the hydrogenation performance of metal hydrides will be reviewed. Techniques, like high-pressure torsion, equal-channel angular pressing, cold rolling, fast forging and surface modification have been widely applied to induce lattice defects, nanocrystallization and the formation of abundant grain boundaries in bulk samples and they have the potential to up-scale material production. These plastically deformed materials exhibit not only better H-sorption properties than their undeformed counterparts, but they possess better cycling performance, especially when catalysts are mixed with the host alloy promoting potential future applications.

(a) Dehydrogenation kinetic measurements obtained at 573 K and 1 kPa for nanocrystalline Mg powders catalyzed by Nb2O5 and/or CNTs and for the corresponding HPT-disks. (b) High-resolution lattice image of the cycled HPT-processed Mg + Nb2O5 + CNT composite (inset: selected area electron diffraction pattern).

The continuously increasing energy demand necessitates searching for new solutions to produce and deliver energy in a sustainable way. Renewable energy is a promising alternative to fossil-based energy production and the installed production capacity is increasing each year.1) However, dependence on the weather conditions makes it difficult to integrate it in large number to the existing energy supply system. This is true in particular for solar and wind energy, due to their intermittent operation mode. Hence, large-scale energy storage technologies will be necessary in order to seamlessly connect them to the grid in the future.

One of the promising energy storage technologies is based on the use of hydrogen as an energy vector.2,3) Hydrogen has a large energy density per mass unit (120–140 MJ/kg) and its use in fuel cells does not produce harmful byproducts.2,4,5) Since hydrogen cannot be found in molecular form on Earth, the first step of the hydrogen-based economy has to be the production of hydrogen. Although there have been developed several methods for this task, the long term production of hydrogen should be based on renewable energy.4) In the next step hydrogen should be stored and delivered to the location of use. Finally, the chemical energy stored in the form of hydrogen is converted to electrical energy using fuel cells. Each of the above steps has its own technological challenges, in this review we focus on the storage of hydrogen.

A hydrogen storage system has to meet different requirements in order to be effectively applied in practice. It should possess high gravimetric and volumetric hydrogen density, proper charge and discharge rate at the appropriate temperature/pressure ranges and long operational cycle life.6) In the past decades, a lot of effort was invested in the development of material-based hydrogen storage systems, due to their potential to achieve increased volumetric capacity compared to the traditional storage technologies, i.e. gaseous and liquid-state storage.5,7,8) Material-based hydrogen storage is mostly realized either by physisorption, i.e. adsorption of hydrogen on the surface of a material or chemisorption, i.e. storage in the bulk of the material. The former group consists of carbon nanostructures, zeolites and other materials with large surface area,5,9,10) for chemisorption-based storage different metal hydrides, complex hydrides and chemical hydrides are used.9,11,12) Among the numerous materials, metal hydrides have significant potential for hydrogen storage as they offer relatively large storage capacity by volume and good reversibility.12,13)

In order to further enhance the properties of hydrogen storage materials, such as the kinetics of hydrogenation/dehydrogenation reaction, different nanostructuring techniques are employed.14,15) Nanostructured materials often present large surface area and grain size typically less than 100 nm which is accompanied by significantly increased grain boundary fraction compared to coarse-grained materials. These features can promote the interaction with hydrogen and enhance the hydrogen diffusion capability of the material, respectively. One of the most frequently used methods to prepare nanostructured hydrogen storage materials is high energy ball milling (HEBM).16,17) While this technique can provide one of the best results in terms of improving the hydrogen storage properties of different materials, unfortunately it also suffers from some problems when it comes to upscaling and practical use.18) The process usually takes relatively long time and is energy-intensive, in addition to the need of protective gas environment.19) Thus, it is desirable to have alternative methods that can be used more easily at industrial level.

Although a large number of processing techniques based on severe plastic deformation (SPD) developed recently and have been applied to produce different types of materials, including metals, alloys and compounds, composites, glasses with exceptional structural properties,20) only a few of them were used to process materials for improving their hydrogen storage performance.21) Generally, SPD induces plastic strain in a bulk piece of material via a top-down mechanism, which yields a fragmented nanocrystalline or sub-micron structure.22–24) At the same time a huge number of lattice defects, i.e. vacancies, dislocations, phase boundaries, twins are formed within the total volume of the material.20) These zero, one and two dimensional lattice defects together with cracks can serve as easy pathways for hydrogen diffusion to improve the overall H-sorption performance of different hydrogen storage systems.15) Unlike HEBM, the SPD processed samples are formed in bulk shape with relatively low surface area, which can result in significantly enhanced air resistance.25)

Among different SPD methods, high-pressure torsion (HPT),26) equal-channel angular pressing (ECAP)27) and cold rolling (CR)28) are the most frequent ones for H-storage, however, other techniques, such as fast forging (FF),29) surface modification by attrition treatment (SMAT)30) and accumulative roll-bonding (ARB)31) are also in the forefront of research and applications. In the present paper we review the latest research and development on improving the hydrogen storage properties of metal-hydride nanomaterials processed by different SPD routes. In Section 2 the advances of the HPT, ECAP, CR, FF and SMAT technologies will be discussed in details. Since each SPD procedure is a top-down technique, it is essential to compare and correlate the nanostructural features of the processed materials with their hydrogenation performance, these observations will also be highlighted in this section. Section 3 compares the advantages and disadvantages of the individual SPD methods from different aspects, while the synergetic effect of the combination of different SPD routes will also be demonstrated. The last section (Section 4) summarizes the future perspectives and potential applications.

Among the different techniques based on SPD, high-pressure torsion exhibits the highest shear strain in bulk sample volume.22) In an excellent review, Edalati and Horita demonstrated that the HPT technique originally was invented by Bridgman in 1935.32) During this processing technique a bulk or pre-compacted disk is placed between two stainless steel anvils and exposed to simultaneous uniaxial pressure of several GPa and concurrent torsional straining. The accumulated shear strain along the radius of the disk can be given by

| \begin{equation} \gamma = \frac{2\pi Nr}{L}, \end{equation} | (1) |

| \begin{equation} \varepsilon \approx \mathit{ln} \left(\frac{\theta r}{L}\right) = \ln \left(\frac{2\pi Nr}{L}\right). \end{equation} | (2) |

Schematic representation of the HPT device.35)

A recent thorough overview demonstrated that high-pressure torsion has successfully been applied to produce a large variety of different H-storage systems.36) When MgH2 powder is subjected to compaction and HPT deformation, a remarkable nanocrystallization takes place,37) which positively influences the H-storage behavior. In addition, the uniaxial stress applied during HPT induces a strong (002) texture and a complete transformation of tetragonal α-MgH2 into a high pressure metastable γ-MgH2 phase38) after N = 15 revolutions, resulting in a significant decrease of the dehydrogenation temperature. It was also demonstrated that the initial powder particle size of MgH2 has a strong effect on the absorption kinetics.39) When pure magnesium is subjected to HPT, a bimodal microstructure develops, containing nanocrystals and large micron sized recrystallized grains.40) The H-storage performance and the absorption rate improve significantly after N = 10 torsion numbers, mainly due to presence of high-angle grain boundaries. The average lattice defect density (mainly dislocations) can approach the value of the theoretical limit (ρ = 8·1015 m−2) in commercial Mg processed by HPT. These abundant defects can act as hydrogen absorption sites.41) The extreme hydrogenation/dehydrogenation stability of a ZK60 Mg-alloy processed by HPT was proved by the marginal decrease in the amount of absorbed/desorbed hydrogen up to 100 hydrogenation cycles.42)

The application of HEBM prior to HPT can promote mechanochemical routes resulting in the formation of intermetallic compounds with advantageous H-storage properties. For example, the Mg2Ni compound formed by a solid state reaction between Mg and Ni presents a synergetic combination of advantageous thermodynamics43) and improved hydrogen sorption by increasing the recombination/dissociation rate of hydrogen atoms/molecules at the grain boundaries.44) Plastic strain generated by HPT can increase the maximum hydrogen capacity of ball-milled Mg70Ni30 nanopowders by 50% due to increased number of one dimensional lattice defects, e.g. dislocations which act as new hydrogen absorption sites.45) Two dimensional defects, like stacking faults can also improve the kinetics of Mg2Ni processed by HPT,46) in addition, abundant cracks also act as pathways for hydrogen transport from the surface in ultrafine Mg + 2 wt.% Ni powder processed by HPT.47) The synergetic combination of HEBM and subsequent HPT deformation route effectively preserves the nanostructure of Mg–Ni during the entire hydrogenation-dehydrogenation process.48) Partially hydrogenated of Mg75Ni25 powder processed by HEBM + HPT revealed the formation of Mg2NiH0.3 hexagonal solid solution and monoclinic Mg2NiH4 hydride phase.49) Interestingly, a significant hydrogen uptake was observed in an otherwise non-absorbing MgNi2 compound due to the extreme shear deformation developed during torsional straining.50) When a powder mixture of Mg + 5 wt.% Ni + 2 wt.% Nb2O5 is subjected to HPT, hydrogen sorption can be obtained at temperature as low as 423 K.51)

A series of research undoubtedly confirmed that hydrogen-storing metastable phases can develop in Mg-based immiscible systems (such as Mg–V–Sn and Mg–V–Ni,52) Mg–V–Cr,53) Mg–Ti54) and Mg–Zr55)) by HPT. In brief, the ultra-severe plastic deformation can extend the solubility of the minor component, which can promote the development of new potential hydrogen storing materials.

Recent investigations have been dedicated to the addition of carbon nanotubes (CNT) to nanocrystalline Mg to improve the capacity and kinetic sorption performance.56–58) Based on this research, it is established that CNTs provide fast diffusion channels during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation for the hydrogen atoms through the passivated surface layer into the bulk material. Lately, it was demonstrated that the processing parameters of a combined HEBM + HPT synthesis route strongly affects the sorption performance of nanocrystalline Mg catalyzed by Nb2O5 and/or multiwall CNTs.59) As seen from the desorption kinetic measurements (Fig. 2(a)), the addition of Nb2O5 plays a crucial role to attain suitable hydrogen capacity, however, it is also evident that severe torsion deformation and the addition of CNT catalyst to ball-milled Mg powder can further improve the desorption kinetics as they act as diffusion channels for hydrogen.60) The observed improvement was attributed to a texture that developed during the HPT procedure and preserved during cycling. As one can realize, the CNT sections presented in the corresponding transmission electron micrograph are preserved during the plastic deformation of HEBM + HPT and subsequent sorption cycling, see Fig. 2(b).60) In a recent paper it was explored that the synergetic catalytic effect of the simultaneous application of metal-oxide particles and CNTs can be replaced by single metal-oxide nanotubes.61) When titanate nanotubes are mixed with Mg during a HEBM + HPT deformation route, a significant reduction of the average crystallite size takes place, coupled with the development of a strong texture. Furthermore, the hydrogenation performance is considerably influenced by the processing route, i.e. longer co-milling yields better dispersed and partially damaged titanate sections that promotes significantly enhanced kinetics.

(a) Dehydrogenation kinetic measurements obtained at 573 K and 1 kPa for nanocrystalline Mg powders catalyzed by Nb2O5 and/or CNTs and for the corresponding HPT-disks. (b) High-resolution lattice image of the cycled HPT-processed Mg + Nb2O5 + CNT composite (inset: selected area electron diffraction pattern).60)

As a non-magnesium based alloy, TiFe intermetallic compound is a potential hydrogen storage candidate, mostly in stationary applications. In order to avoid hydrogen activation at high temperature, mechanical activation routes based on severe plastic deformation methods were applied to TiFe, when substantial improvement in the room temperature hydrogen absorption was observed after HPT processing.62,63) This alloy is capable to absorb 1.7 wt.% of hydrogen at room temperature without any prior thermal activation procedure (see Fig. 3) and maintain its hydrogen absorption performance even after several hundred days of storage in air.64) Thus HPT not only activates TiFe but also prevents its deactivation upon exposure to air.

Pressure-composition isotherms obtained at room temperature (303 K) for TiFe intermetallic alloy processed by (a) annealing at 1273 K for 24 h under argon and (b) HPT processing for N = 10 turns in air.62)

The hydrogenation behavior of fully disordered systems, like metallic glasses can significantly be improved when the material is subjected to severe shear deformation by HPT.65) Originally these materials are synthesized by highly non-equilibrium techniques, including melt spinning and copper mould casting.66,67) When a melt-spun Mg65Ni20Cu5Ce10 nanoglass subjected to torsional straining, the H-sorption kinetics improves significantly.68) As seen in Fig. 4, the alloy performed at N = 1 rotation shows the highest capacity and fastest kinetics among all the deformed samples. These enhancements are attributed to the abundant pathways for hydrogen diffusion at the interfaces between the nanoglass regions that are developed during the HPT-process. When HPT is applied to a compacted Mg65Ni20Cu5Y10 glassy alloy, deformation induced Mg2Ni nanocrystals develop in the residual amorphous matrix that can reduce the dehydrogenation temperature of the system.69) At the same time, the formation enthalpy of the hydrogenation increases remarkably which is the most pronounced at the perimeter region of the HPT-disk.70) When CNTs are added to the melt-spun Mg65Ni20Cu5Y10 amorphous alloy before HPT straining, the electrochemical hydrogen absorption capacity increases substantially, confirming that nanotubes play a crucial role in the absorption of hydrogen of Mg-based glasses subjected to severe plastic deformation.71)

Hydrogenation kinetics of melt-spun and HPT-treated Mg65Ce10Ni20Cu5 glassy alloys, at an initial pressure of 3.0 MPa and at a temperature of 120°C.68)

Equal channel angular pressing is a severe plastic deformation method that imposes deformation on the specimen by pressing it through two intersecting channels. Figure 5(a) illustrates a schematic cross-section of the tool. The intersection of the two channels is described by two angles as shown on Fig. 5(a).72) As the sample is pressed by a plunger it is only able to move through the intersection by plastic deformation and the resulting (equivalent) strain can be expressed as:73)

| \begin{equation} \varepsilon_{N} = \frac{N}{\sqrt{3}}\left[2\,\mathit{cot}\left(\frac{\Phi}{2} + \frac{\Psi}{2}\right) + \Psi\,\mathit{cosec} \left(\frac{\Phi}{2} - \frac{\Psi}{2} \right) \right], \end{equation} | (3) |

(a) Schematic cross-section of the ECAP tool and (b) the different processing routes.72)

ECAP is often used to process bulk hydrogen storage materials in order to enhance their hydrogen storage properties due to its being a fast and relatively cheap processing technique. A recent study demonstrated the effect of ECAP processing on the hydrogen sorption properties of commercial AZ61 magnesium alloy.75) As the number of ECAP passes increased up to N = 8 the hydrogen absorption/desorption time decreased and also the hydrogen absorption capacity increased. These improvements are thought to be related to the microstructural changes during ECAP processing, as it was shown that the average grain size of the material is decreased with the number of passes (from 100 µm to 10.61 µm during N = 8 consecutive passes). The increased fraction of grain boundaries have dual roles, on one hand they can provide numerous nucleation sites for the hydride phase, on the other hand, they can also facilitate the diffusion of hydrogen that is generally faster along grain boundaries. Another paper compared different deformation routes and it was revealed that route Bc (see Fig. 5(b)) is the most efficient for the enhancement of absorption kinetics and capacity of AZ31 magnesium alloy.76) Route Bc was found to produce the lowest grain size (5 µm) and lowest dislocation density (5.4·1015 m−2). While the beneficial effect of the small grain size is not surprising, it was argued that the low dislocation density is also advantageous for hydrogen sorption as it was reported in some cases that edge dislocations can act as hydrogen traps.76–78)

Another interesting feature of the ECAP processing is that the severe plastic deformation procedure can induce the crystallization of second phase particles. In particular, Mg17Al12 formation was observed for AZ6175,79) and AZ31 alloys;76,80) the content of the intermetallic phase was increased with increasing number of passes.76,79) Addition of materials, such as Ni and SiC to these alloys results in the formation of AlNi, Al3Ni, Mg2Ni and Mg2Si phases during ECAP.79,80) It is believed that these second phase particles serve as catalysts for hydrogen absorption and desorption processes. Other additives, such as different carbonaceous materials81,82) or Ti-based materials83) were also tested in combination with the ECAP deformation procedure. It was established that additives, such as carbon black, can improve the grain refinement effect of the ECAP and in turn increase the capacity.81)

Long-term cycling stability was tested on an ECAP deformed ZK60 magnesium alloy.84) The kinetics and reversible capacity showed remarkable stability, the material practically maintained its sorption performance through 1000 absorption-desorption cycles (see Fig. 6). In comparison, high-energy ball milled samples do not show such behavior.

Hydrogen (a) absorption and (b) desorption kinetic curves measured at 350°C against cycle number for a ZK60 alloy after 4 passes of ECAP.84)

Comparison was also made between ECAP deformed and ball milled Mg catalyzed by multiwall carbon nanotubes. Equal channel angular pressing results in markedly different sorption kinetics than high-energy ball milling, i.e. initially the milled sample shows faster kinetics, while at later stages of the reaction its hydrogen release slows down and the ECAPed sample has the higher desorption rate.82) The authors pointed out that the ECAP processed sample has a significantly higher density of defects in the Mg matrix, which can accelerate the kinetics of desorption. Another study on ECAP processed AZ31 alloy demonstrated that ECAP results in increased hydrogen absorption capacity compared to the ball milled material, in addition it was also shown that the activation energy for desorption is slightly lower for the ECAP deformed sample.80)

2.3 Cold rollingCold rolling is a commonly used procedure to severely deform bulk materials at room or below room temperature. It uses two rollers rotating in opposite directions, the specimen is pushed through the gap between the rollers (see Fig. 7(a)). During this process the sample undergoes plastic deformation, and the equivalent strain can be given as:85)

| \begin{equation} \varepsilon = \frac{2}{\sqrt{3}}\mathit{ln} \left(\frac{t_{0}}{t_{f}}\right), \end{equation} | (4) |

Schematic picture of the (a) cold rolling procedure and (b) groove rolling device.63)

Hydrogen storage materials usually require an activation procedure, i.e. breaking the passivation layer, which most often forms on the surface in spite of careful preparation, by hydrogenation-dehydrogenation cycle(s). However, by using SPD methods, for example CR, the activation time can be reduced or practically eliminated as was demonstrated in case of Mg6Pd alloy.87) The cold rolled material presented very similar absorption curves for the first and second cycle, which was significantly enhanced compared to the activation performance of the ball milled reference sample. Nevertheless, after the activation process the milled specimen had a higher sorption rate than the rolled material. Comparison between the effect of HEBM and CR on the sorption of MgH2 was also made by S.D. Vincent and J. Huot.88) They demonstrated that 5 repetitions of cold rolling in air results in similar absorption-desorption kinetics than 30 minutes of ball milling in air. However, they also pointed out that milling time exceeding 30 minutes in air has a detrimental effect on the capacity and kinetics of MgH2. At the same time, it is possible to carry out further rolling passes without any degradation of hydrogen storage performance according to Ref. 89). In fact it was demonstrated that Mg rods rolled for 300 times are able to absorb hydrogen at a temperature as low as 150°C. CR was also shown to be an effective tool to activate Mg samples which subsequently presented fast H-sorption kinetics.90) Based on these examples, it is clear that cold rolling has the ability to produce samples with superior resistance against the contamination of air compared to ball milling.

The problem of passivation is not only occurs for Mg-based materials but also for other hydrogen storage materials as well, such as TiFe. Normally TiFe can be activated under high pressures (in the order of megapascals) and at a high temperature of 673 K. However, it was shown that mechanical activation using either CR, groove rolling (GR), HEBM or HPT is a promising alternative. For instance, CR completely eliminates the need of any further activation procedure, providing fast kinetics already during the first absorption at room temperature and at a pressure of 2 MPa.91) The hydrogen absorption rate even exceeded that of the material activated by high-energy ball milling. Another report also showed that TiFe + 4 wt.% Zr alloy deliberately exposed to air for several days can also be reactivated by cold rolling, i.e. the material readily absorbed hydrogen at room temperature without any incubation time.92) GR and HPT were also successfully applied to mechanically activate TiFe.63) The groove rolled sample left in air for 150 days was able to absorb hydrogen and leaving it one further day in air does not deteriorate it sorption capability at all, indicating its resistance against deactivation in air. It was suggested that the enhanced sorption performance is a result of the microstructural changes occurring during severe plastic deformation, namely the formation of dislocation cells, slip bands, cracks and numerous grain boundaries. These microstructural features can act as pathways for hydrogen through the oxide layer. It is important to note that mechanical activation does not clear away the passivation layer, it only makes it permeable to hydrogen, hence, the material becomes more resistant to further exposure of oxygen.

Beside activation, i.e. altering the surface layer of the material, CR can also refine the microstructure of the whole material. It was shown that cold rolling can effectively reduce the average crystallite size of MgH2 powder in a much shorter time than ball milling can.93) The reduction of the crystallite size and also the particle size has led to increased capacity and higher hydrogenation rate. Rolling can also be carried out at cryogenic temperatures as was demonstrated recently on an AZ91 magnesium alloy.94) The idea behind this is that at lower temperatures the dynamic recovery processes that normally occur during severe plastic deformation can be suppressed. Indeed, it was found that the low temperature (liquid nitrogen temperature) rolling results in a more refined microstructure and more cracks on the surface than that is achieved by rolling at room temperature. Consequently, a significantly better hydrogen absorption and desorption kinetics was observed after CR at lower temperatures (Fig. 8(a)). Beside the refinement of microstructure of the main phase, CR was also shown to promote the fragmentation and dispersion of second phase particles, such as the MgZn2Ce intermetallic phase in Mg-based ZK60 alloy + 2.5 wt.% mischmetal.95)

ARB offers the possibility to manufacture composite specimens via the repetition of folding and rolling of different bulk materials. For example, Mg–Ti, Mg-stainless steel multilayer composites96) and Mg–LaNi5-soot composites97) were successfully synthesized. It was shown that these composites have better hydrogen sorption kinetics than the rolled bulk Mg samples without any additives. Thus, it is clear that the ARB process can improve the hydrogen storage performance in multiple ways, i.e. structural refinement and the introduction of secondary phases that can act as nucleation sites for the MgH2 (see Fig. 8(b)).

Composite formation can also be achieved by CR of powder blends as was demonstrated for multiple material combinations.98–100) MgH2 and LaNi5 powders were cold rolled under argon atmosphere that resulted in the decrease of particle size.98) While formation of new phases did not occur during the rolling procedure, it occurred after the first dehydrogenation-hydrogenation cycle that confirmed the good mixing of the two materials. Different metal, metal-oxide and metal-fluoride additives were successfully mixed with MgH2 by the application of CR, among the tested materials FeF3 incorporation resulted in the largest decrease in the desorption temperature.101) Another paper has shown that addition of Fe to Mg by CR in air is an effective way to improve the absorption capability of the material.100) Formation of Mg2FeH6 hydride phase was observed after hydrogenation which indicates that the rolling procedure was able to produce enough new interface area between the two starting phases for the transformation to take place. It should be pointed out that such transition did not occur without rolling (as-mixed power blend). CR was also found to yield better sorption performance than hot extrusion in case of a composite of Mg, Fe and carbon nanotubes.99)

2.4 Forging 2.4.1 Fast forgingFast forging, a less conventional technique based on severe plastic deformation can operate at larger scales and shorter times compared to the other methods mentioned earlier in this article, therefore it can satisfy practical requirements, including mass production. In brief, this technique incorporates a free falling hammer of mass of 150 kg, released from 1.5 meters with a forging time of less than 0.02 s onto a piston which is in direct contact with a cylindrical sample placed on an anvil located within a chamber as shown in Fig. 9.29) Conventional forging rates (5 × 10−3 s) results in flat disks with a thickness of 2 mm. The typical sample height reduction ratio during a single drop-forging is about 75%, equal to a true strain of ∼1.4,102) which value is lower than the achieved strain by HPT processing.103) Since the mechanical energy of the hammer is practically dissipated in the whole volume of the sample, it can induce large plastic strain, and as a consequence significant crystallite size reduction and the creation of abundant lattice defects.29,104) Such nanocrystallization is expected to improve the hydrogenation performance similarly to other SPD methods.

An earlier research on the mechanical processing of MgH2 + 5 wt.% Fe by fast forging resulted in good dispersion of the catalyst particles, significant nanocrystallization, however, the lower specific surface promotes a high air-resistance compared to HEBM powders.105) Besides microstructural refinement, FF is capable to induce solid state reactions in Mg-based hydrogen storage materials. For example, fast forging a mixture of Mg and Ni powder compact promotes the formation of Mg2Ni intermetallic compound with improved kinetic performance.29) In order to maximize the Mg2Ni phase content in the sample, a 2D simulation model of the cell was constructed based on adiabatic compression.106) By increasing the applied temperature above a threshold value (400°C), the complete conversion of the Mg + Ni powder mixture takes place into a Mg + Mg2Ni bulk alloy.107) Hydrogen absorption below the threshold temperature is mainly governed by the formation of defects and cracks in the Mg particles, enhancing hydrogen diffusion into the bulk, on the other hand forging at elevated temperature yields the formation of Mg2Ni nanocrystals as a catalyst, see Fig. 10.108) The most favorable hydrogen sorption performance was achieved for the Mg–22 wt.% Ni alloy when annealing is followed by the fast forging deformation method that generates cracks combining with the formation of fine Mg2Ni nanocrystals (favorable for desorption) and textured Mg grains (favorable for absorption).109) These findings confirm that the FF technique is an efficient SPD route enabling mass production of hydrogen storage materials.

X-ray diffraction patterns of the Mg–22 wt.% Ni alloy after FF at temperatures (a) 210°C, revealing no phase transformation and (b) 480°C with the significant formation of Mg2Ni.108)

A very recently developed advanced SPD method called accumulative fold-forging (AFF)110) was applied to produce nanostructured Mg–Ni layers with enhanced hydrogen storage capacity.111) The basic concept of this technique is to involve repetitive stacking and forging of metallic layers, as illustrated schematically through Figs. 11(a) to 11(h).112) Since Mg does not have sufficient formability as a foil, instead it was used in powder form and Ni was applied as a foil to support the required steps of the AFF treatment. The multiple step of AFF forging up to 20 cycles generated as many as 1,048,576 layers within the composite structure. The optical images of the fold-forged products are seen in Figs. 11(i) to 11(k). The AFF treatment promotes a drastic improvement on the H-storage capacity of the Mg/Ni multilayered composite due to the formation of millions of nanometric interfaces. In addition, the H-release characteristics can be adjusted by the Mg:Ni stoichiometry.

Schematic images illustrate the subsequent stages for the accumulative fold-forging method. (a) Primary nickel foil, (b) introduction of magnesium powder onto the Ni, (c) first stacking of foil layers, (d) pressing to bond the stacked layers, (e) U-bending for continuing the fold-forging steps, (f) subsequent folding stage, (g) next forging and (h) final state of composite layer structure containing 1,048,576 layers. (i) The real primary nickel foil with magnesium powder, (j) folded structures of Mg–Ni and (k) final fold-forged products of multilayered structures.112)

A novel SPD method induced by surface plastic straining was developed by Lu and coworkers by modifying the uppermost layer of a bulk material by SMAT.113,114) Besides of surface nanocrystallization and gradient microstructure of the top layer of the bulk material,78,115) different chemical reactions can also be accelerated.116) In brief, the SMAT procedure involves repeated multidirectional impacts by flying balls to induce severe plastic deformation in the surface layer of a target sample that is vibrated by a vibration generator see Figs. 12(a) and 12(b).30) Each impact will induce a severe plastic deformation with a high strain rate resulting in the formation of dislocation blocks, high angle grain boundaries and surface nanocrystallization.

For hydrogen storage materials, lattice defects (mainly dislocations) and grain boundaries form in the defected surface layer can act as pathways for hydrogen transport through the oxide layer and activate the material, see Fig. 12(c).78) Nevertheless, the majority of material is coarse-grained below the top deformed region with low density of lattice defects, hydrogen can be stored reversibly in this coarse-grained area, particularly at the sub-surface.78) By comparing the hydriding performance of Ti–V–Cr alloy processed by HPT and SMAT, it is concluded that due to surface lattice defects on initial activation, both materials readily absorb hydrogen at room temperature. Nevertheless, the SMAT-treated alloy exhibits remarkable hydrogen reversibility, while the HPT-processed material has poor reversibility due to bulk defects hindering the hydrogen transport.117)

Scanning electron microscope images taken on the cross-section of commercial Mg treated by SMAT indicate that the surface of the treated sample is uneven, surface shearing and folding are dominant, see Fig. 13. It is also noticed that cracks develop perpendicular to the surface, which are favorable for accelerated hydrogen diffusion.118) After longer processing time, the abundant ball-to-target collisions can induce removal of hardened Mg particles (chips) from the top layer and later they can be re-deposited onto some parts of the fresh and active surface of the target disk. As a consequence, hydrogen absorption can occur without activation, as the maximum capacity is reached after the first full absorption-desorption cycle. The detectable maximum hydrogen uptake increases gradually with the SMAT treatment time, confirming that Mg or Mg-based alloys processed under air by a bulk SPD technique are capable to absorb hydrogen.118)

SEM images taken on different parts of the cross section of the Mg-disk treated by SMAT.118)

While it is clear that all the above detailed techniques can improve the hydrogen storage properties of metal hydrides, it is important to examine the strengths and weaknesses of these methods compared to each other.

A. Grill et al. compared the effect of different SPD techniques on the hydrogen sorption and cycle stability of Mg-based materials.42) Both ECAP and HPT yielded fast kinetics and excellent cycle stability (stability through 1000 and 100 cycles, respectively) for ZK60 alloy. On the other hand cold rolling of MgH2 resulted in slower hydrogenation/dehydrogenation and also the reduction of the capacity was observed with increasing cycle number. It was argued that these differences were caused by the use of different materials, in particular the lack of impurity atoms in MgH2 that could stabilize the defects introduced by plastic deformation as in the case of ZK60. Part of these defects is eliminated due to the elevated temperatures used during sorption reactions that ultimately results in the deterioration of sorption performance.

The importance of lattice defects is also highlighted for other oxygen-sensitive materials, like TiFe63) and Ti–V–Cr alloys.78) Activation of these materials is carried out mechanically by HPT or GR and HPT or SMAT, respectively. In both cases HPT activated the specimens more easily than the other techniques. This is due to its larger imposed shear strain and the larger fraction of grain boundaries and lattice defects/distortions. However, it was also shown that the HPT-deformed alloys are not able to desorb as much hydrogen as the groove rolled or SMAT-processed materials. It was argued that the poor reversibility is caused by the high density of defects, such as dislocations that apparently hinder the hydrogen transport and can act as traps for hydrogen.

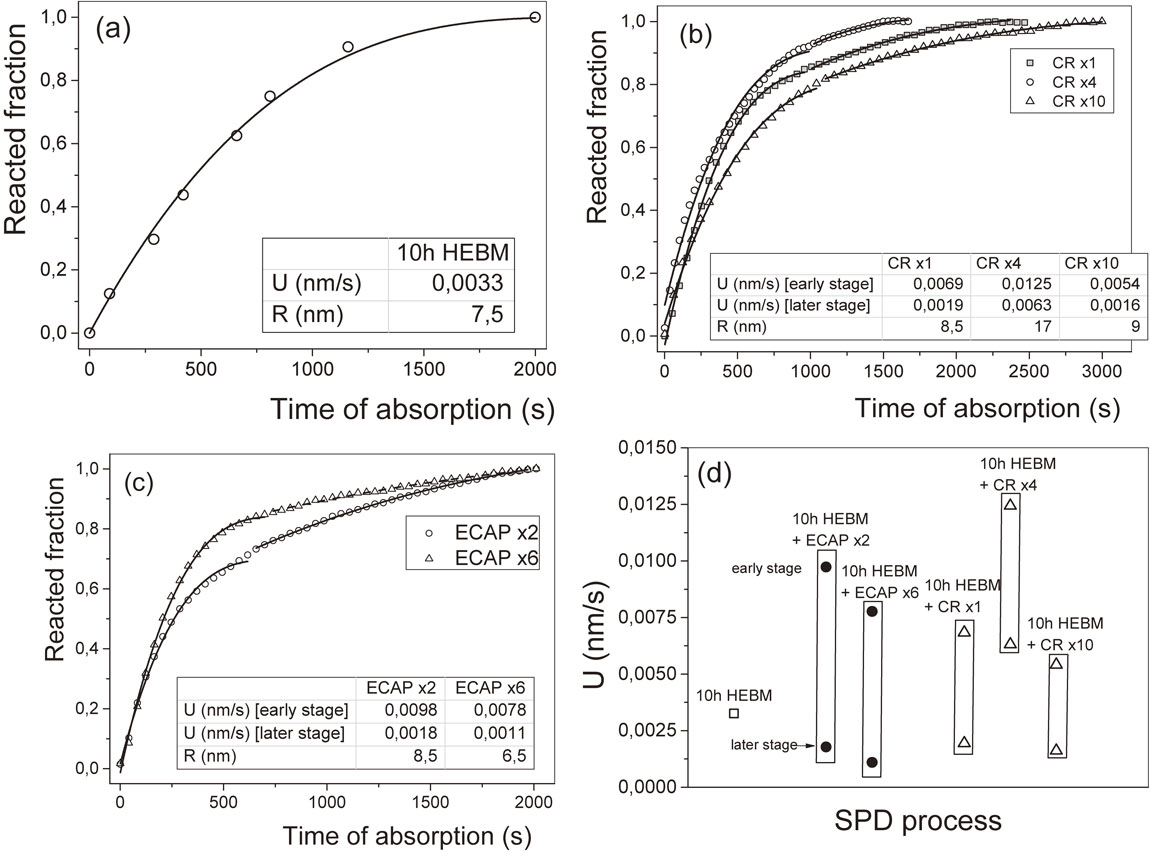

CR and ECAP were applied to deform ball milled Mg2Ni samples and the hydrogen absorption kinetic curves were compared.119) It was found that by using CR the absorption capacity of the material can be significantly increased over the one processed by ECAP, additionally the initial absorption rate is also higher in case of rolling. The kinetic curves were attempted to fit by the contracting volume model which describes the reaction as a hydride-metal interface moving with constant velocity:120)

| \begin{equation} \alpha_{CV} = 1 - \left(1 - \frac{U}{R}t \right)^{n}, \end{equation} | (5) |

Hydrogen absorption kinetic curves fitted by the contracting volume model for (a) ball milled, (b) milled + cold rolled, (c) milled + ECAP deformed Mg2Ni alloys and (d) the hydride-metal interface velocities.120)

A.M. Jorge Jr. and coworkers used cold rolling on an ECAP processed Mg sample and found a correlation between the amount of (002) texture and the hydrogen sorption performance.122) Numerous other investigations also indicated that cold rolling induces a strong (002) texture in magnesium,87–89,94,99,122,123) in contrast to ECAP for which only the longitudinal section of the material showed such texture.124) It was suggested that the existence (002) texture promotes the hydrogen absorption. On one hand, the (002) direction presents atomic positions with lower energy for the hydrogen atoms to enter the Mg matrix than other directions. On the other hand, there is an orientation relationship Mg(002)//MgH2(110) and this transformation is assisted by the large amount of (002) texture. However, it is not only the texture that determines the sorption properties but also the grain size as pointed out in Ref. 123). For example, at the early stages of desorption the kinetics was found to be influenced by the grain size to a larger extent than by texture. Thus combination of CR with its ability to create preferential texture and ECAP with its better grain refining ability is a promising route to produce better hydrogen storage materials. Indeed, separate studies on the severe deformation of ZK60 revealed that combining different SPD methods, namely, the use of ARB after ECAP (see Fig. 15)124) and the use of ECAP after CR125) can further improve the kinetics and capacity of the material compared to the use of only a single technique.

Hydrogen absorption (a), (c) and desorption (b), (d) kinetic curves of an ECAP and ECAP + ARB processed ZK60 alloy measured at 623 K, under 2 MPa and 100 kPa pressure, respectively.124)

In the present review we demonstrated that severe plastic deformation is an efficient tool to synthesize a large variety of hydrogen storage systems. In general, all the SPD methods improve the hydrogen storage of materials by refining their microstructure, generating grain boundaries, inducing lattice defects, hence improving the diffusion of hydrogen and the nucleation of the hydride phase. However, the different SPD processes can produce quite different microstructures (different kind and amount of defects, texture etc.) and as a result they can influence the hydrogen sorption differently. For example, HPT exhibits the largest equivalent strain among all the SPD techniques, thus it results in the finest microstructure with the most lattice defects. In most cases this is advantageous, however, for certain materials a different approach is recommended. The gradient microstructure generated by SMAT enables to investigate the structural dependence of hydrogenation and the fine-tuning of the surface structure. Generation of texture may also be important, for this task HPT and cold rolling were found to be the most effective. Formation of new phases, crystallization of second phase particles and composite formation were achieved for all the SPD processes, however certain methods, in particular ARB and AFF are especially useful. It is up to the specific hydrogen storage material that determines which method is the most suitable to use. In fact, combining different techniques is a promising way to achieve even better material properties as they induce different microstructural features. It is also important to note that selecting the proper materials or material combinations is just as crucial as choosing the right SPD methods. For example, the refined microstructure produced by the deformation procedure should be preserved through multiple absorption-desorption cycles. Suitable additives can improve the cyclability and sorption stability of the hydrogen storage material.

In addition, practical aspects, like upscaling, processing time and easy industrialization are also important points. Some techniques are difficult to scale-up and are still mainly used at a laboratory level (e.g. HPT). ECAP, CR and FF techniques have greater potential for commercial applications; however, in order to achieve a threshold for commercialization in the future, several issues should be addressed. For example, heat transfer and cycling stability of bulk deformed specimens should be further investigated. Hydrogen sorption temperatures should be decreased while maintaining reasonable kinetics. Combination of the different SPD techniques and additives has a great potential to achieve such improvement hence further studies is recommended in this area.