2024 年 36 巻 1 号 p. 77-82

2024 年 36 巻 1 号 p. 77-82

The stem of vascular plants serves as foundational support for aboveground growth. Tissue response to mechanical forces is crucial for directing plant morphogenesis and, thus, stem growth and shape. This process plays a pivotal role in expanding the size of aboveground organs while also dictating the spatial arrangement of leaves and flowers. However, external forces can sometimes result in tissue or organ breakage. Hence, the stem must integrate forces beyond a certain threshold to control its development. In this minireview, I will focus on recent findings on Arabidopsis thaliana lines displaying deep cracks in their inflorescence stems and their research backbones are summarized. These recent studies reveal a more complex picture than previously considered regarding the relative contributions of vascular and epidermal tissues to stem mechanics and growth.

Cylindrical tissues in vascular plants, such as stems and hypocotyls, have been the primary focus of biophysical research since the early days of molecular biology (Masuda and Yamamoto 1972, Shibaoka, 1972, Peters and Tomos 1996, Niklas, 1992). The tissue tension theory was proposed by Hofmeister in the 19th century, and it was confirmed that internal tissues would expand in volume and protrude when a crack was introduced on the epidermis of a plant segment submerged in water (Hofmeister 1859, Sachs 1865, Kraus 1867). With ongoing advancements in live imaging techniques, we can now quantify the behavior of cell growth and the dynamics of cellular processes. This allowed us to better understand the influence of mechanical signals on morphogenesis and served as an indicator of the direction of tension built on the cell wall. By capturing the pattern of forces through examination of the morphology and deformation associated with growth, our understanding of plant development based on mechanical transduction has improved considerably (Hamant et al. 2008, Trinh et al. 2021).

Mechanical cues in plants can be primarily categorized into two types: "shape-derived" and "growth-derived" stresses (Hamant and Haswell 2017). Shape-derived stress is generated by a high turgor pressure (positive pressure), which is constantly maintained within plant cells and serves as a significant tensile stress component within the cell wall. The turgor pressure is inherently isotropic and exerts a force perpendicular to the cell wall surface.

On the other hand, growth-derived stress is generated by cell expansion itself. When plant cells grow in a specific direction, an imbalance in tensile stress occurs on different faces of the cell wall, leading to anisotropic cell growth (Moulia 2013). Since plant cells adhere to each other through cell walls. Consequently, the growth of one cell can alter the behavior of surrounding cells and induce deformation (Figure 1). These geometrical changes are fed back to the original cell, resulting in modifications to the growth direction and extent. These changes propagate from cell to tissue, a local to a global scale, ultimately leading to alterations in the mechanical arrangement at the tissue level (Hamant and Saunders 2020, Nakayama et al. 2022). The relationship between the mechanical properties of the cell wall and turgor pressure-based cell growth model also applies at the organ level, with a typical example being cylindrical tissues such as stems. When considering a stem organ as a single cell, the epidermal tissue corresponds to the cell wall, while the internal tissue of the stem corresponds to the protoplasm within the cell membrane.

The inflorescence stems of vascular plants exhibit radial symmetry when viewed from a transverse section. In the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana, a representative of angiosperms, the stem comprises various types of tissues. The outer parenchyma contains epidermal, cortical, and endodermal cells, while the inner parenchyma primarily comprises pith cells and occupies a larger volume than the outer parenchyma. Xylem tissue is located between the parenchymal tissues. The epidermal tissue of the stem is often viewed as a "pressurized vessel" exposed to the turgor pressure resulting from the growth of the internal tissues (Kutschera 1989, Baskin and Jensen 2013). It is estimated that the maximal tensile stress occurs along the circumferential direction of the epidermis. The mechanical theory supports the idea that a turgor-pressurized condition is essential for the standability of stems (Kanahama and Sato 2023).

Figure 1. Mechanical cues guide differential growth.

Mechanical signals derived from cell growth and growth-induced stress. Differential (anisotropic/uneven/asymmetrical) growth deforms the surrounding cells, is transmitted across the tissue, and changes the geometry of surrounding cells. The orange arrows indicate the growth direction of the central cell. Purple arrows indicate the growth of the surrounding cells originating from the central cells. Only the growth direction of surrounding cells caused by growth of the central cell (orange arrow, center to right) is indicated. The biased restriction of growth drives anisotropic growth via microtubule guidance of cell wall reinforcement, which aligns with parallel to maximal tension direction in growing cells. Blue arrows indicate the turgor pressure of the central cell. Black arrows indicate the feedback loop for biased growth.

Although plant biomechanics has primarily focused on analyzing the physical properties of fully developed organs, the question of how mechanical integrity is maintained within these organs remains another fundamental issue. Plant growth is inherently associated with substantial mechanical stress. However, considering that there are limits to the strength of the cell walls, these forces must be kept within these limits. Stem integrity includes both mechanical (material) and structural (topological) properties. Practically, cell wall abnormalities that lead to reduced strength or imbalanced growth have resulted in tissue- and/or organ-level damage in Arabidopsis mutants. This mechanical failure is not confined to cylindrical tissues but is also observed on the 2D surfaces of leaves (Verger et al. 2018, Malivert et al. 2021). Furthermore, aside from the stem of Arabidopsis, mechanical failures of the skin of flesh spherical fruits have been widely recognized (Considine and Brown 1981, Asaoka and Ferjani 2023).

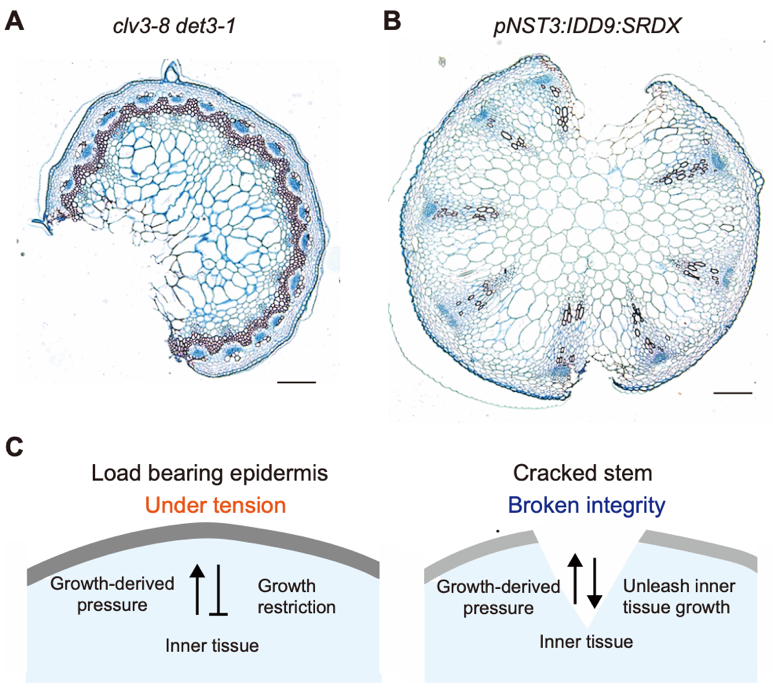

Recently, the signaling underlying growth coordination in stems has been highlighted, notably building on different mechanical properties (Serrano-Mislata and Sablowski 2018). The recent research focused on exploring the scientific side of the intriguing phenomenon of stem cracking in Arabidopsis (Figure 2A, 2B, Asaoka et al. 2021, 2023), and identified at least three mechanical components crucial for sustaining stem integrity: the load-bearing epidermis, which resists inner cell growth; regulation of cell proliferation within inner tissues; and growth heterogeneity associated with vascular bundle distribution in deep tissues.

Figure 2. Epidermal control of stem growth.

(A, B) Histological images of stem cracks obtained by Asaoka et al. (2021) for (A) and Asaoka et al. (2023) for (B) but not used in these articles. Bar = 100 µm. The sections were stained with Astra Blue and Safranin. (C) Mechanical feedback was made visible by breaking stem integrity. In the WT stem, the epidermis (gray) was under tension, restricting the growth of the inner tissue. When excess inner tissue growth breaks the epidermal integrity, inner tissue growth is unleashed.

The stem-cracking phenotype (i.e., deep longitudinal cracks within inflorescence stems) was initially observed in the severely dwarfed mutant of Arabidopsis: the clv3-8 det3-1 double mutant with molecular lesions in both CLAVATA3 (CLV3) and DE-ETIOLATED3 (DET3) genes, exhibiting deep longitudinal cracks within their inflorescence stems (Maeda et al. 2014). clv3-8 det3-1 was obtained by screening seeds of the det3-1 mutant that had been irradiated with a heavy-ion beam (Maeda et al. 2014, Ferjani et al. 2015). The goal of this screening was to identify mutants with novel morphological characteristics in their stems, even though the original det3-1 mutant displayed severe dwarfism (Schumacher et al. 1999). Time-course analyses demonstrated that stem cracks were most frequent in clv3-8 det3-1 stems when they reached approximately 2 cm in length (Asaoka et al. 2021).

The CLV3 peptide signal is perceived by receptor kinase proteins, CLV1 and CLV2, which suppress WUSCHEL, which ultimately controls shoot apical meristem size. The clv3 mutant exhibit over-proliferating meristems (Clark et al. 1997, Laufs et al. 1998, Ogawa et al. 2008). Stem cracking was observed in combinations of det3-1 and other clv mutants. Whereas the cracking frequency was almost 100% in clv3-8 det3-1 stems, it was 37% and 35%, respectively, in clv1-4 det3-1 and clv2-1 det3-1 stems (Maeda et al. 2014), suggesting that defects in CLAVATA (CLV) signaling have a key factor in stem cracking in the det3-1 background. By quantifying inner stem tissue morphology, we identified a correlation between the extent of cell proliferation and the frequency of stem cracking in the above lines (Asaoka et al. 2021).

The cracking phenotype enables us to revisit stem development, notably through substantial differences in the elastic strain between the epidermis and inner tissues (Baskin and Jensen 2013). Upon examining the cross sections of cracked stems, we observed that the pith cells were deformed and elongated towards the cracking site (Figure 2A). We confirmed the increase in the volume of the inner tissue after stem cracking by comparing the actual cross-sectional areas versus theoretical cross-sectional areas calculated based on the peripheral stem length (Asaoka et al. 2021). It has long been a well-known theory that the epidermis controls growth by restricting inner growth (Kutschera and Niklas 2007). However, this “epidermal theory” remains debatable as it does not apply to all plant tissues (Galletti et al. 2016). Nevertheless, our results support, at least at this stage, a scenario where the epidermis constrains growth in the stem and that stem cracks promote inner tissue growth by weakening epidermal growth constraints (Figure 2C).

We further hypothesized that stem integrity depends on the epidermal resistance to mechanical stress. By applying indentations using atomic force microscopy, we confirmed a reduction in cell wall stiffness in the det3-1 stem epidermis (Asaoka et al. 2021). In the epidermis-specific complementation line of DET3 (pPDF1:DET3 clv3-8 det3-1), the occurrence rate of stem cracks was reduced by 20% (Asaoka et al. 2021). These findings indicate that the inadequacy of load-bearing resistance in epidermal tissue is related to crack formation in clv3-8 det3-1. Furthermore, they emphasized that the mechanical balance achieved through the regulation of cell number (CLV3) and maintenance of the structural integrity through epidermal cell wall stiffness (DET3) underlies the mechanical integrity of the stem.

We previously reported another Arabidopsis line that exhibited stem cracking (Figure 2B, Asaoka et al. 2023). This line was identified through large-scale genetic screening, in which genes encoding transcription factors were fused with either an activator or a repressor domain (SRDX; Hiratsu et al. 2003) and systematically transformed into nac secondary cell wall thickening promoting factor1 (nst1) nst3 double mutants under the control of the NST3 promoter. Note that the nst1 nst3 mutant exhibits a pendent stem phenotype (Mitsuda et al. 2007). The original screening was conducted to identify transgenic lines that rescue this stem pendent phenotype, and as a result, novel AP2/ERF transcription factors were identified for their role in primary cell wall synthesis (Sakamoto et al. 2018). This seed library was used to screen for plants exhibiting a stem-cracking phenotype, and the pNST3:IDD9:SRDX line (IDD9, INDETERMINATE DOMAIN9) was identified. While the stem in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX remained pendent, the stem growth of pNST3:IDD9:SRDX was nearly comparable to the WT. Following stem development, the first crack primarily occurred at 9–11 days after bolting, corresponding to the period when the height of the inflorescence stems reached 13–19 cm long (Asaoka et al. 2023).

Cross-sections of pNST3:IDD9:SRDX stems exhibited a radial expansion of approximately 2-fold compared with that of the WT and lacked lignin staining in the fiber tissue (Asaoka et al. 2023). Quantification of cellular parameters revealed distinct characteristics in both the epidermis and fiber tissue (Asaoka et al. 2023). Despite radial expansion in the pNST3:IDD9:SRDX stems, the number of epidermal cells in the stem periphery and their cross-sectional areas were comparable to those in the WT. In the fiber tissue, which comprised multiple cell layers, the cells in all the layers displayed enhanced radial expansion. Although growth primarily occurs longitudinally in stem organs, radial cell expansion in the pNST3:IDD9:SRDX stem results in increased epidermal stress. Because NST3 is expressed in fibers, excessive cell expansion in the pNST3:IDD9:SRDX fiber may be the primary phenotype caused by SRDX-fused IDD9 and may also be the driving force behind heterogeneity of the mechanical properties of the tissue and the subsequent formation of cracks.

The vascular bundle in the stem consists of the xylem and phloem, with vessel and fiber cells in the xylem forming a secondary cell wall that contributes to water/nutrient transportation and provides postural support, similar to a pillar. Histological analysis revealed that the role of vascular bundles in stem integrity was not specific. To our knowledge, none of the histological sections exhibited disrupted vascular bundles in the stem cracking lines. This observation suggests that although the stiffness of vascular bundles contributes to stem integrity, it also creates weak points in their vicinity, leading to mechanical heterogeneity within the stem organ (Asaoka et al. 2023). Because the number of vascular bundles increased in the clv3-8 mutant, which was associated with an increase in the meristematic region in the shoot apex, we generated pNST3:IDD9:SRDX transformants in the clv3-8 background to analyze whether changes in tissue and/or cellular parameters affected stem cracking. This analysis revealed that the number of cracks increased in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX clv3-8 stems, but that each crack was smaller and shallower than the cracks in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX (Asaoka et al. 2023). In summary, the local strength, number, and arrangement of stem vascular bundles can fundamentally influence stem mechanical integrity.

Since stem organs are composed of various cell types, the characteristics of the cell walls among them are diverse. From a mechanical perspective, it is essential to consider not only the composition of polysaccharides, such as the size of the cellulose fibrils and the distribution of matrix polymers such as hemicellulose and pectin crosslinking, but also the thickness of the cell walls. Remarkably, the cell walls of epidermal cells are thicker than those of the inner tissues. Within epidermal cells, the cell walls on the outer periphery are thicker than those on the inner side (Kutschera 1992). Our observations of stem epidermal cell wall thickness in Arabidopsis using transmission electron microscopy revealed that the cell wall of the outer periclinal wall was approximately 4–5 times thicker than the inner periclinal wall (Asaoka et al. 2023). When comparing the epidermal cell wall between WT and pNST3:IDD9:SRDX, it was particularly noteworthy that cells in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX appeared flatter, and the inner periclinal walls were thinner (Figure 3, Asaoka et al. 2023). Interestingly, the anticlinal walls were thicker in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX than in WT, possibly because of the accumulation of tension on this side of the cell wall, resulting in subsequent reinforcement of the cell walls; however, this explanation remains speculative. At least, these observations indicated a distinct response of epidermal cells in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX to tensile stress.

The flattening of epidermal cells during stem growth was quantified in Asaoka et al. (2021). In clv3-8 det3-1, despite the increase in stem inner volume and the number of pith cells, the number of epidermal cells in the stem remained constant throughout the examined growth period (ca. 2 weeks). The shape of the epidermal cells was quantified using the cell aspect ratio (R), which was calculated by dividing the breadth (the maximal length of an epidermal cell along the edge of the stem) by its thickness (the maximal length of an epidermal cell in the radial direction of the stem). Flatter epidermal cells have greater R values, and a drastic increase in R value was confirmed for clv3-8 det3-1 (Asaoka et al. 2021). These results suggest that epidermal cell flattening likely occurs in response to an increased tensile stress during stem growth.

Figure 3. Quantification of epidermal cell flattening.

(A, B) Representative cross-sectional images of the stem epidermis. Images were obtained and quantified as described by Asaoka et al. (2023). Bar = 100 µm. (C) Distribution of the cross-sectional size and cell aspect ratio of epidermal cells were calculated using the method described by Asaoka et al. (2021). The cell aspect ratio of the WT (1 cm stem) was analyzed by Asaoka et al. (2021) and was newly displayed on a log2 scale in this study. Cross-sectional images from Asaoka et al. (2023) were used for quantification and analysis of mature WT stems and pNST3:IDD9:SRDX.

In previous research, only the very early stages of the WT were examined, and pNST3:IDD9:SRDX was not quantified using this index. Therefore, the focus here is on comparing the WT and pNST3:IDD9:SRDX or younger and older stems in the WT, based on cross-sectional images of stem epidermis of 1 cm stem of the WT (Asaoka et al. 2021), the basal part of the mature stem of the WT (stem height was around 30 cm, Asaoka et al. 2023), and the basal part of the mature stem of pNST3:IDD9:SRDX (Asaoka et al. 2023). The average cell areas were comparable, which was 179.9 ± 45.5 µm2 in the WT (1 cm stem), 166.4 ± 58.0 µm2 in the WT (mature stem) or 170.6 ± 62.3 µm2 in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX (mean ± s.d.); however, the cell aspect ratios were quite different (Figure 3). The epidermal cell aspect ratio was significantly higher in pNST3:IDD9:SRDX and higher in the mature WT stems compared to the younger ones. In younger stems, larger epidermal cells exhibited a flatter shape, but at maturity almost all cells were flatter than in younger stems, and there was no correlation between cell size and shape (Figure 3). These observations align with the concept that the epidermis must bear the volume increase of the inner tissue using pre-existing material, which leads to stretching of the inner periclinal walls.

Recent findings have highlighted the significance of stem integrity in understanding plant shoot development. However, there remain some missing pieces in this puzzle. Although leaves and stems are fundamental components of shoots, the functional genes associated with stem development remain poorly characterized. Furthermore, fundamental insights into the entire developmental process in stems, such as how epidermal cells grow, how many inner parenchymal cells divide and expand in stems, how these cells differentiate, and whether there is coordination, are still ill-known. Another issue is the potential difference in gene expression in response to mechanical cues in stem organs, as observed in the shoot apex (Landrein et al. 2015). Genes in the stem epidermis may respond differently from those in other tissues because the stem epidermis is highly pressurized. The link between morphology and regulation of gene expression can be elucidated by recognizing the flattening of stem epidermal cells as a sign of mechanical cues. The vascular bundles respond to weight through a process known as vertical proprioception (Alonso-Serra et al. 2020), which is the ability of an organism to sense its shape and growth (Hamant and Moulia 2016). Plant’s own weight is not the only cue for proprioception; Plants constantly experience fluctuating internal and external mechanical cues along with fluctuations over time are assumed to contribute to plant shaping (Moulia et al. 2021). Given that stems are bending back and forth continuously, how fluctuations are coded and how they influence morphogenesis remain curious questions. The stem is not merely a simple cylindrical structure. Biomechanics is believed to be a promising approach for elucidating the complex nature of morphogenesis.

The author gratefully acknowledges Dr. Ali Ferjani (Tokyo Gakugei University) and the contributors to the stem crack research. The author is also grateful to the members of the selection committee for the Encouragement Prize 2023 of the Japanese Society of Plant Morphology for their careful consideration. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan and a Grant-in-Aid for Research Activity Start-up (21K20662 to M.A.). The author thanks Dr. Olivier Hamant (INRAE-Lyon) and Prof. Kazuhiko Nishitani (Kanagawa University) for critically reviewing the manuscript.