2024 Volume 12 Pages 24-44

2024 Volume 12 Pages 24-44

The institutional history of agricultural co-operatives in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China has similarities in terms of pre-establishment, establishment, and development stages, but relatively different in the side of recognition and introspection, as well as the choice stage. Among the four countries, the initiators of agricultural co-operatives establishment are not only the community/grassroots movement, respectable individuals, and non-governmental organizations, but also the government. Once the government oversees agricultural co-operative development, it uses its political power to position the organization as a state agency. By that, facilities are given to accelerate the policy makers’ goals and positively impact the agricultural co-operatives’ organizational growth. However, the farmer-members in Japan recognized that the co-operatives do not accommodate their needs. Later, with the aid from the new-regime government, the agricultural co-operative in the country was gradually reinvented. In South Korea, the farmer-members disagree with the decision from the government to use agricultural co-operatives as parastatal. Therefore, they later pooled their resources, urged changes, and successfully ran the agricultural co-operatives per se. On the other hand, in Indonesia, when the government loosened its ties, agricultural co-operatives with sufficient human resources reinvented or spawned the organization. In contrast, the ones with poor management quality chose the status quo or exit. In China, the loophole in the government policy encouraged more private companies or prominent capital entrepreneurs to run the co-operatives instead of farmers. Consequently, agricultural co-operatives with no actual member farmers focused on commercial activities unrelated to the members’ needs or placed the farmers merely as the users, not the decision-makers, could be found within the country. The review of institutional history emphasizes the importance of further study about the longevity of government-led and non-governmental-led agricultural co-operatives.

Agricultural co-operatives play a strategic role in the agriculture value chain (input of supply, production, collection, processing, or retailing). The entity could help the producers access cheaper inputs (lower transaction cost) because the farmers are encouraged to pool their purchasing power and buy in bulk [1]. In terms of production, the enterprise might influence farmers’ agriculture practices and production choices. It also could help farmers reach economies of scale because of lowering average or per-unit costs for a larger scale of operation [2, 3]. Moreover, from the post-harvest aspect, the co-operative could collect, transform, package, and later sell the commodity. The farmer members, therefore, might have better access to the market or a stable market channel [4,5].

The member-owned organization also has a strategic role in agricultural and related commodities’ global value chain (GVC). According to Tran et al. [6], GVC is a process involving multi-activities and multi-party to bring a product from its conception until its end use, within one nation or overseas. In Ireland, the Department of Agriculture, Food and Marine [7] stated that agricultural co-operatives contributed to processing over 98% of nationwide milk production and exporting the product. Meanwhile, USDA [8] emphasized that the enterprise owns and operates plants that process milk and sell 70% of the milk marketed in the US. Moreover, Zen-Noh [9] highlighted that Japan Agricultural Co-operative (JA) conducts business from supplying input for farming to marketing the product nationwide and overseas.

According to ICA [10], the top ten agriculture and food industry co-operatives consist of organizations from the USA (3), Europe (4) and Asia (3). In terms of the number of countries or regions, USDA [11] reports there were 1,779 agricultural co-operatives in the USA in 2019. Meanwhile, Ajates [12] pointed out more than 40,000 agricultural co-operatives in Europe. Lastly, Dongre [13] explained that agricultural co-operatives were the first type of co-operative to emerge in most Asian countries. Furthermore, there are around 2,398,972 units of agricultural co-operatives throughout Asia (Appendix 1).

In Asia, Japan (Zen-Noh) and South Korea (Nonghyup) are the two countries that consistently on the top 10 largest co-operatives in agriculture and food industries sector for the last ten years [14]. On other words, Asia played a strategic role in the dynamics of agricultural co-operatives worldwide. However, there is a lack of information regarding the literature review about institutional history that compare countries in Asia. In fact, examination of institutional history will explain about the pre-establishment, establishment, growth-glory-heterogeneity, recognition and introspection, and choice that the agricultural co-operatives have taken in order to face the dynamics of organization and business. In general, scholars studied comprehensively one country or conducting case studies, such as Sri Lanka and Japan [15], Japan and Thailand [16], China and Vietnam [17], Cambodia and South Korea [18], and Japan and Korea [19].

Kurimoto [20] explained that co-operatives’ dynamics are influenced by public policy, institution, and culture. Therefore, literatures regarding those three aspects will be examined to describe the institutional history of agricultural co-operatives. However, among countries in Asia, only four nations will be investigated, namely Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China. Years ago, Japan controlled the area within South Korea, Indonesia, and China, including the agricultural co-operative mobilization. Moreover, in each country, agricultural co-operatives work in a hierarchical system, but only the federation in Japan emerged as a powerful farm lobby group, meanwhile in South Korea controlled by the government and later ruled by the farmers. On the other side, the federation in Indonesia was initiated by the co-operatives members and in China encouraged by the government, but de facto it is not always the case that primary co-operatives have to join the federation.

This study has two contributions to the current literature. First, it expands the understanding of agricultural co-operative development because the situation in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China may differ in terms of social, political, and economic conditions. Also, institutional history could be contrasted with the situation in Western countries. Second, by examining the literatures regarding the institutional history which consists of the initiators and their initiatives, the formation of rules of game for the organization, development progress and its challenges, and the current situation, this study will portray how the different situations in the four countries influence the development process of agricultural co-operatives in every nation.

Studies about agricultural co-operative history explained that before the organization’s establishment, there were already traditional agricultural cooperation, traditional cooperative movements, or cooperative associations, including in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China (Table 1). It is being called “traditional” because those activities are less institutionalized, present more of a code of conduct based on moral principles and some of them emerged as traditional practices of mutual help on an ad hoc basis [21, 22]. A study has found that a person is not only a natural or economic person but also a social person. Therefore, kinship (the relations between an individual and the spouse, parents, sisters and brothers, and cousins), social relations, and potential relations might determine social participation [23].

Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China started their economic development as agrarian countries. In the past, most people lived in rural areas/villages and had work related to the agricultural sector. Furthermore, people in villages have different needs. Therefore, they form various associations or movements, from storing rice for emergencies to exchanging work to saving and credit for repairing wells, roads, bridges, or other typical facilities (Table 1). In relation to agricultural activities, work exchange became common because one family could not handle labor-intensive seasons such as planting and harvesting. Jung and Rösner [21] and Onda [24] explained that in South Korea, peasants help each other or reciprocal exchange of labor (pumashi) in both quantity and quality. Similarly, Wong [25] explained that in China, when relatives or friends agreed to come to help each other for mutual benefit (pien-kung), the risk of conflicts arising from demanding rigid reciprocal treatment was considerably reduced because of the equal amount of work or labor. Moreover, Onda [24] found that labor exchange still exists in farming activities. Therefore, it could be further investigated how the mechanism works in the middle of modernism, mechanization of agriculture, and the introduction of wage labor.

| Country | Traditional Cooperative Movement | Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Shasoh | Storing rice for emergency | [26] |

| Mujinkoh and Tanomoshikoh | Creating a fund and the money was loaned to a person who needed funds to recover from disaster or to create a new line of business | ||

| Hotoku-sha | Establish the coexistence of economic prosperity and moral uplift | ||

| Senzokabu Kumiai | Administrating the hereditary rights of farmland | ||

| South Korea | Hyangyak | Working toward solidarity and mutual help in reciprocal social relationships | [21] |

| Bobusang | Traveling merchants that sell goods | ||

| Pumasi | Exchange of work | ||

| Dure | Collective farming | ||

| Gye | Collecting and administering funds for financial assistance in case repairing common facilities | ||

| Indonesia | Gotong-royong | Incidental social cooperation | [27] |

| China | Pien-kung | human labour exchange | [25] |

| Jen-kung pien-kung | labour-animal exchange |

People in rural villages also need more capital. Hence, they pool their resources to create a fund and give credit to those in need. Ishida [26] found that Raiffeisen from Germany inspired Hotoku-sha in Japan. This association at the village level was based on the concept of mutual self-help and with the mission to enhance welfare at individual and community levels. On the other hand, Hatta [27] explained that the situation in rural areas in Indonesia requires a co-operative credit system. Still, due to the Indonesian mentality and social structure, it could be attained only with great patience and in slow stages. Therefore, to tackle the problems immediately, the modern co-operative movement in the country is imposed from above (local government), in contrast with the traditional association or even the traditional patterns of the co-operative organization itself.

In China, various co-operative movements were carried out in rural China and the primary initiators consisted of NGOs, scholars, and social reformers [28]. The initiators were influenced by Western co-operative practices, especially in Germany. Germany became a role model because, at that time, the social structure in Germany was relatively similar to that of Asian countries [26]. Furthermore, the Raiffeisen model or Schultze Delitzsch model in Germany successfully enhanced the peasants’ economy. Moreover, there are three ways for Asian countries to adopt the co-operative model from the Western countries, namely sending the representatives, the initiators who previously had the chance to study in the country and try to implement the same movement in their own country, and scholars from Western country paid a visit to Asian countries [26, 27, 28, 29].

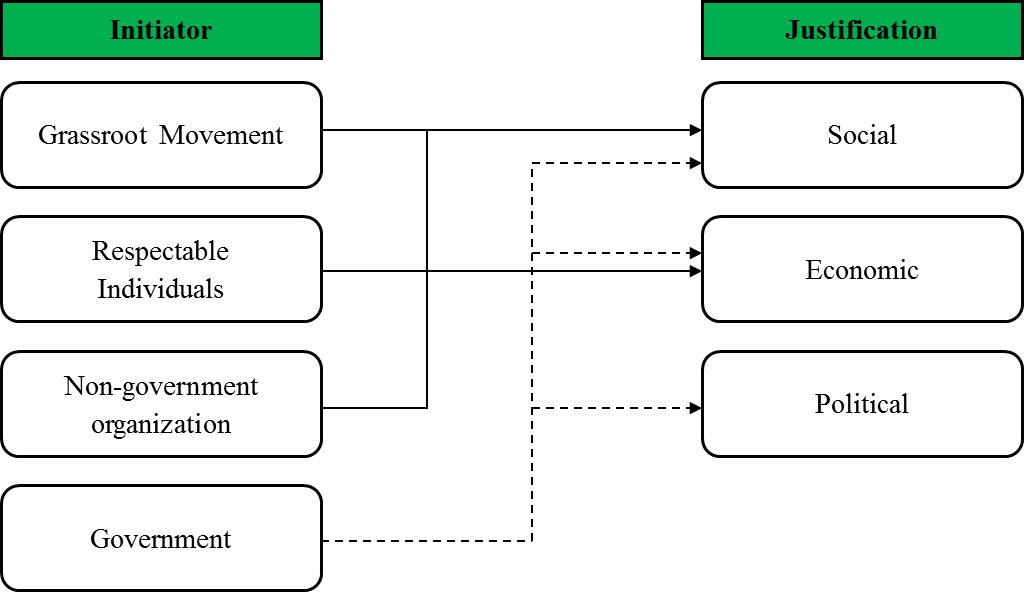

The justification for establishing co-operatives varies among different initiators. The grassroots movement, NGOs, or respectable individuals commonly aimed for social welfare and economic enhancement to form the organization. Meanwhile, the government is concerned with social, economic, and political aspects (Figure 1). Political justification in this study could be explained as the effort by the government to ensure the existence of its ideology, accelerating its own development goals, or as the measure of the success of program realization [28, 30]. Moreover, another form of political justification happened in South Korea and Indonesia before the Independence Day of each country. The colonial government used agricultural co-operatives as the agency to exploit the resources and connect them to the colonial economy [21].

The initiatives to establish agricultural co-operatives differ between the countries selected in this study and the Western countries. First, it is not merely the economic aspect but also the social value that already exists in the community that makes the formation of agricultural cooperative work [26]. Second, the government in selected countries intervened in the agricultural co-operatives and used its political power to drive the organization. On the other hand, CHS Inc. in the US and Friesland Campina in the Netherlands are two of the top producer co-operatives in the world, initiated by a group of people to protect and enhance the economic well-being of rural communities [31, 32, 33]. Both co-operatives started their journey with economic justification and acted as joined forces with the producers to combat market failure [34, 35].

Cook [36] explained that after the co-operative organization form is chosen to accommodate the stakeholders’ goals, the following process sets up the organizational design. Additionally, most co-operatives studied by Cook are bottom-up approach organizations. Therefore, the study explains that the most challenging element of organizational design is agreeing on well-defined performance metric(s) and achieving member consensus. However, a different case might occur when the government oversees the rules of games by implementing a top-down approach.

Indonesia, South Korea, and China declared their Independence Day in 1945, 1948, and 1949, respectively. Before Independence Day, there was not only intervention by local government but also by the colonizers (Figure 2). Consequently, instead of accelerating the organization, Hatta [27] found that the Dutch colonial government introduced co-operative legislation in Indonesia to prevent its further development. Similarly, Hatta [27], Jung and Rösner [21], and Wan [28] explained that during Japan’s occupation, the co-operative movement was getting worse. Japanese colonial government changed the co-operative bylaws and used the co-operative to exploit and integrate the resources into its economy. Contrastingly, Ishida [26] highlighted that the Japanese government enacted the co-operative law in 1900 to provide four kinds of co-operative: credit, purchasing, marketing, and production.

In Japan, Ishida [26] explained that the Co-operative Society Law was modeled after the Raiffeisen in Germany. It also duplicated the bylaws, such as the freedom of entrance and exit, equal rights to vote and make decisions (one man, one vote), limits on dividends, and restrictions on the transfer of equity. Meanwhile, after the Republic of Indonesia’s Independence Day, the government adopted Co-operative principles by the International Co-operative Alliance, such as voluntary and open membership, democratic member control, and member economic participation for co-operative statutes nationwide. Moreover, Rieffel [37] explained that starting in 1963, the government involved agricultural co-operatives to increase food production and credit distribution. Later, Santoso [38] exposed that a presidential instruction was enacted as the foundation for strengthening the organization (amalgamating agricultural co-operatives in villages into village unit co-operatives that cover one sub-district).

According to the Ministry of Government Legislation of South Korea [39], the first law concerning Agricultural Co-operatives in the country consisted of 145 articles, starting from general provisions, purpose and area, business, establishment, union members, institutions, accounts, supervision, division, merger and dissolution, liquidation, registration, city, country and district agricultural co-operatives, horticultural co-operatives, livestock co-operatives, special agricultural co-operatives, national agricultural co-operatives association, until penalties. To establish an agricultural co-operative, the law requires a minimum of 20 people to organize the organization.

Chan and Ip [40] emphasized that the Common Program in China in 1949 gave several mandates to the government in terms of co-operative development, four of which are: the state should protect the properties of co-operatives (Article 3), the government should assist in the development of a co-operative economy and provide preferential treatment (Article 29), State trading bodies had responsibility to assist the people’s co-operative business (Article 37) and working people were to be encouraged and assisted in developing co-operative businesses (Article 38). Article 38 also emphasized the establishment of supply and marketing co-operatives, consumer co-operatives, credit co-operatives, primary production co-operatives, and transport co-operatives in towns and villages.

Muthuma [41] studied co-operative development policies and their impact on the co-operative development. The study concluded that although co-operatives are autonomous self-help organizations, their performance could be affected by government policies defining their engagement with the market. In relation to that finding, the Co-operative Society Law, enacted by the Japanese government in 1900, was the first law concerning co-operatives, including agricultural co-operatives, among selected countries in this study. During 1900–1945, Ishida [26] found that the law was revised ten times to adjust the co-operative with the current dynamics. Münkner [29] studied the worldwide regulation of co-operative societies. A study by Münkner could be followed for further investigation of how the Raiffeisen and Szhulze-Delitzsch model and ICA principles adopted in Asian countries as the statutes and bylaws impacted the co-operative development.

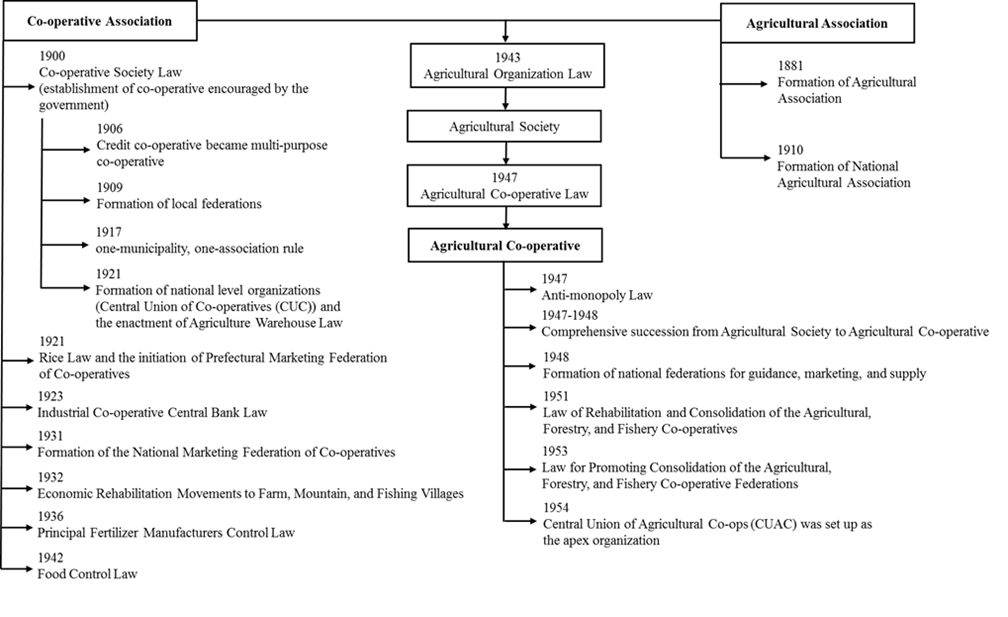

Agricultural co-operatives development is relatively different between the ones initiated by the non-governmental party (grassroots movement, respectable individuals, or NGO) and the government itself. In Japan, Shinagawa, as the secretary for home affairs, and his subordinate, Tosuke Hirata, spread information about the importance of co-operatives since 1891. Ishida [26] informed that after seven years (1898), the movement established around 351 co-operative associations. On the other hand, after the Japanese government enacted the Co-operative Society Law in 1900, in less than five years, there were more than 3,000 co-operatives (Figure 3).

Kurimoto [20] stated that government regulation would influence the co-operative’s behavior. During the establishment phase, the government only allowed co-operatives to run a single business unit. However, after 1905, the policymakers revised the Co-operative Society Law and allowed the credit co-operatives to become multi-purpose co-operatives. Consequently, the number of multi-purpose co-operatives increased rapidly, outnumbering the single-purpose (purchasing, marketing, and production) co-operatives from 1910.

Ishida [26] concluded that multi-purpose co-operatives are dominated by co-operatives that conduct purchasing, marketing, production, and credit business units. Kurimoto [20] pointed out that various business units aimed to cover major economic activities in rural areas. Moreover, aside from comprehensive services, the government legalized favorable regulations to ensure its goals could be realized, including amalgamating the co-operative associations with agricultural associations into agricultural organizations for the sake of war (Figure 4).

In order to revitalize the co-operative, a new law was legalized in 1947 (Agricultural Co-operative Law [42]). In supporting that, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry took the measures called “comprehensive succession”; agricultural co-operatives took over the agricultural organizations’ properties, offices, boards, and employees. The agricultural co-operatives also inherited the primary character of previous organizations as the state agency [20].

Mandal [43] concluded that the agricultural co-operatives development in Japan is mainly due to strong government support, manifest in the acceptance of the co-operatives as a device for implementing the National Agricultural Policy. The economic benefits accruing from the co-operative services and the overall efficiency resulting from the high degree of integration, network and national involvement in the co-operative system of Japan (as shown in Figure 4).

Choi et al. [44] found that the form of government impacted the development of agricultural co-operatives. In South Korea, authoritarian control over society, including the agricultural co-operatives’ activities, such as selecting executives and appointing management in the co-operative. Moreover, to tackle the co-operatives’ financial issue, the government enacted the new Agricultural Co-operative Act in 1961 and amalgamated the agricultural bank with agricultural co-operatives (Figure 5).

The number of agricultural co-operatives grew rapidly. Less than ten years after the new Agricultural Co-operative Act was enacted, Choi [45] found that there were already 16,000 units of co-operative. However, those co-operatives are relatively small, with 139 farmer-members on average. Therefore, from 1969 to 1973, there was a merging action among numerous small co-operatives into fewer, larger co-operatives. This action resulted in fewer co-operatives but with more buying power and a higher possibility of gaining more capital funds since the average number of farmer members of co-operatives increased to 1,400 people.

Burmeister [46] exposed the agricultural co-operatives in South Korea as parastatal, due to the heavy intervention from the government in the organization activities. In other words, the NACF was established as the implementation arm of other central government agencies, especially the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries (MAFF). Concerning that, the organization gained an opportunity to conduct a wide range of businesses, namely fertilizer and other agricultural inputs, savings, and loans, selling consumer goods and insurance (Figure 6).

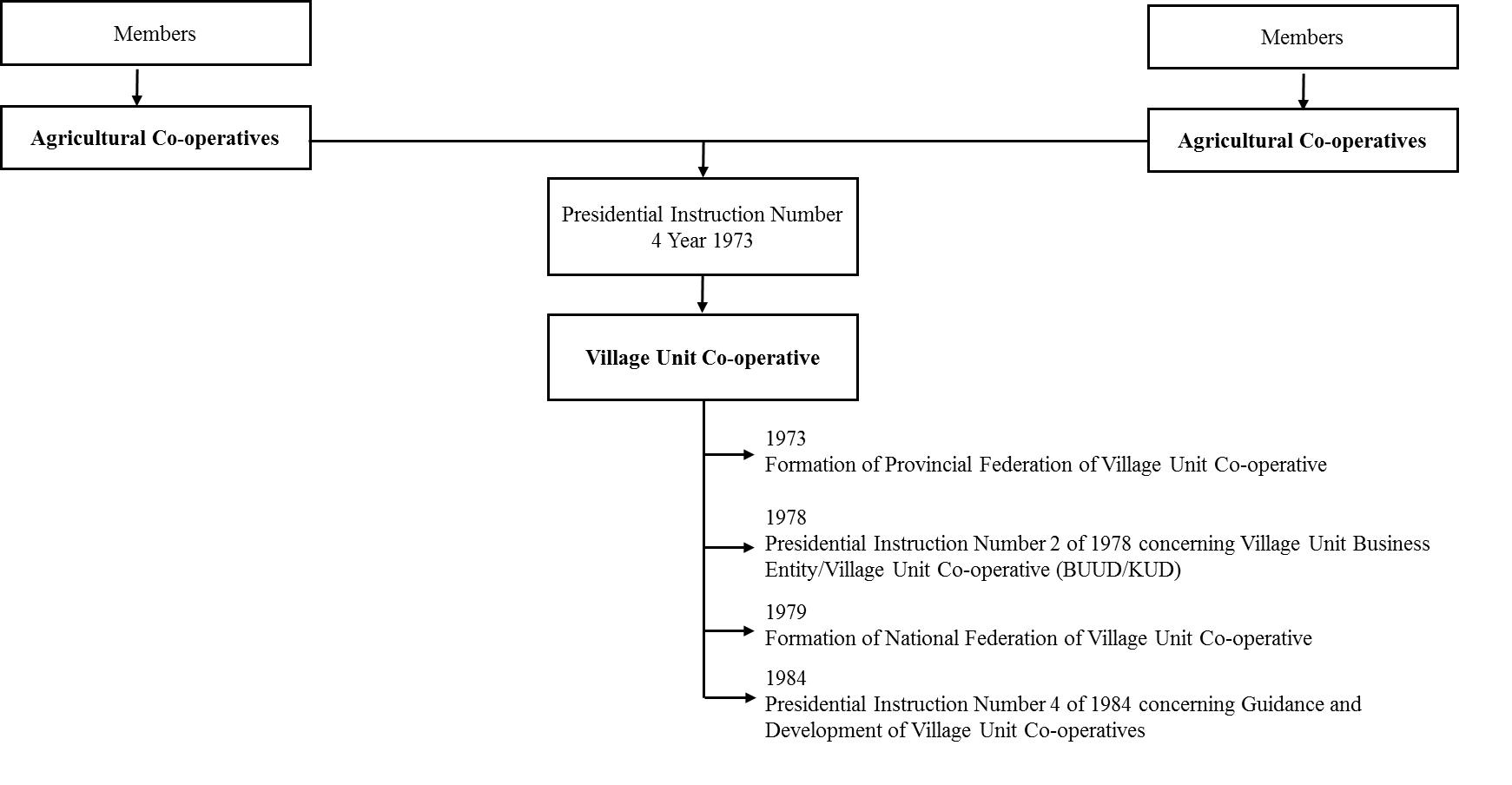

Similarly, In Indonesia, Suradisastra [47] emphasized that the government promoted the village unit co-operative as the main co-operative for producers and people in rural areas since 1973. Rifin and Nauly [48] explained that the village unit co-operative was given responsibilities for providing farm credit, agriculture input, and incentive distribution, marketing of farm commodities, and other economic drivers associated with the co-operative. Additionally, the rapid development of the co-operatives led the government to expand the scope of agricultural co-operatives by issuing Presidential Decree No. 2/1978. This decree promoted the village unit co-operative as a rural economic institution. Moreover, in 1984, the government issued Presidential Decree No. 4/1984 to appoint the co-operatives as the only member-owned organization in rural areas. Consequently, village unit co-operatives experienced positive growth by the government’s support (Figure 7 and Figure 8).

INKUD [49] highlighted the development of the federation system in village unit co-operative in Indonesia, which differs from the system in Japan and South Korea. First, the governments in Japan and South Korea used the national federation co-operatives to manage the agricultural policy, national to the local level (a top-down approach). Therefore, the regulations concern the relationship between co-operatives within the federation system. On the other hand, the government in Indonesia concentrated on the village unit co-operative at the sub-district level to realize its program. In contrast, provincial and national federation-level co-operatives emerged from a bottom-up approach.

Among countries studied in this review, the development of agricultural co-operatives in China is relatively more dynamic. Chan and Ip [40] concluded that ideology becomes the primary reason agricultural institutions in the country change. Firstly, there were elementary co-operatives and advanced co-operatives (Figure 9). Wan [28] described in the elementary co-operative, the means of production were privately owned and maintained but were rented to the co-operative for use. This kind of organization consisted of more than 20 households. Furthermore, advanced co-operatives comprised around 150 households. It is being called advanced because the production was centrally planned and managed, with mandatory participation. Later, Chan and Ip [40] highlighted that because of the promotion by the government, the number of agricultural producers’ co-operatives surged from 0.65 million to over 1.9 million between mid-1955 and the end of 1955. Moreover, by the end of 1957, almost all rural households connected with co-operatives. Secondly, under the ideology of collectivism, the government converted agricultural co-operatives into People’s communes.

Wan [28] found that the People’s Commune, as the government’s project, failed due to ineffectiveness and inefficiency. Collectivization negatively impacted agricultural productivity and food production. Therefore, the People’s commune diminished, and agricultural co-operatives emerged since 1982.

The dynamics of agricultural co-operatives development in China are caused by the ideology and the existence of regulation. Hu et al. [23] explained that in general, after 1982, there were two primary forms of co-operative organization, namely Farmer Specialized Associations (FSA) and Farmer Specialized Co-operatives (FSC). Additionally, to reduce the confusion, Liang and Hendrikse [50] explained that farmer co-operatives and specialized co-operatives are interchangeable. Moreover, Hu et al. [23] stated that because there was no law regulating either FSC or FSA, an overlap occurred, in which some FSA are even co-operative enterprises and act just like specialized co-operatives.

Chan and Ip [40] described that systematic promotion of farmers co-operatives began in 2004. The government conducted experimentation and chose Taizhou in Zhejiang province as the location. The project ran successfully, and later, regional regulation in Zhejiang inspired the national government to enact the first law concerning farmers’ specialized co-operatives in the country.

Zhong et al. [51] found that co-operatives increased massively after the FSC Law was enacted, from 26 thousand in 2007 to nearly 1,289 thousand in 2014. Liang and Han [52] explained that the requirements for the registration of co-operatives stipulated in co-operative law are low, which is favorable for multiple parties, such as local government and officials, to establish the organization. On the other side, Sultan et al. [53] highlighted that the FPC Law gives certainty for the co-operatives to do business and sign the business contract. This factor also has a role in the development of FSC after the law’s enactment.

According to the agricultural co-operative development in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China, government intervention by enacting laws or regulations impacted the co-operative’s behavior. Moreover, to ensure the government’s goals are realized concerning agricultural co-operative development, the policy makers provide the co-operative with subsidies, tax exemptions, monopoly status, guidance, and technical support. In Japan, Freiner [54] highlighted the JA Zenchu as the apex organization of agricultural co-operatives in the country, granted a tax exemption. This status gave JA Zenchu freedom to organize its vast array of activities and using its role as an implementing body for MAFF policies, the organization wielded considerable power. In South Korea, Jin [55] stated the NACF is operated as a monopolistic company with national preferences in the rural society. In other words, it provided credits through deposits and savings to farmers daily, organized sales of agricultural machinery, fertilizers, pesticides, and industrial products, and acted as a government’s proxy agency for purchasing grain from farmers. Similarly, in Indonesia, Widjojo [56] portrayed the government as the promotor of village unit co-operative, operating a single co-operative to cover the needs of people in rural areas and acting in a monopolistic system to provide seeds and fertilizer. Lastly, Bijman and Hu [57] exposed Article 8 of the FPC Law which states co-operatives do not have to pay VAT when selling input to their member. Additionally, customers buying from co-operatives pay 16% less tax.

The government intervention in co-operatives statutes, bylaws, and activities dominates the development phase of agricultural co-operatives. However, the intervention resulted in different ways among Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China. In Japan, Godo [58] and Godo [59] found that the cooperation between the policymakers and the co-operative has resulted in solid political power in the national federation of agricultural co-operatives. The apex organization could lobby political parties and the government to protect the farmers’ interests. In return, the agricultural co-operatives will support political parties during the election.

Maclachlan and Shimizu [60] found that at the national level, the apex organization could lobby the policymakers. Still, the interest might differ between the national federation and the farmer members as the owners of primary co-operatives. The federation system urged the farmers to sell their produce to the federation co-operatives, but it turned out the farmers offered uniform prices to cultivators regardless of variation in product quality. Moreover, in the interview session, Freiner [54] was told by a farmer that “co-operatives do nothing; they have not protected the producers”.

Agricultural co-operatives in Japan (JA) recognized two membership types: regular and associate members. Kurimoto [20] portrayed the number of regular members (farmers and agricultural juridical persons) is decreasing, reflecting the declining farming population. On the other hand, the number of associate members tends to increase yearly. Later, Muchetu [61] explained that because the associate members contribute more revenue, the co-operative has been accused of pursuing a trajectory that shifts the organization’s core focus from the farmers to non-farmers. Additionally, Ishida [26] exposed that full-time and part-time farmers have different interests in co-operative governance. Full-time farmers encourage the co-operative to strengthen its agribusiness unit. In contrast, part-time farmers enjoyed the co-operatives serving multipurpose business units since their main job was non-agriculture related.

Honma and Mulgan [62] studied the political economy of agricultural reform in Japan under Abe’s administration. The study concluded that the different interests between JA and the farmers, the failing number of farm voters, JA’s declining political power, and the urge to turn the farm sector into a profitable industry and “engine” of growth, encouraged Prime Minister Abe to process agricultural reformation, including the transformation of JA. In 2015, the revised Agricultural Co-operative Law was legislated, and it impacted the rules of games of the co-operative and its relationship to the member-owners. According to the revised law, a) local co-operatives are enabled to establish independent businesses and b) the federated system becomes optional so that primary co-operatives could use it or not, depending on its convenience to the system.

Studies have shown that regime changes impacted the agricultural co-operatives’ governance. In South Korea, Burmeister [46] explained that the newly elected president in 1987 marked a turning point in state-society relations in the country. Choi et al. [44] pointed out that in the authoritarian era (1960 to 1987), the farmers’ movement that urged the democratization of NACF remained unheard. However, beginning in 1987, the overall society changed and the movement successfully pushed for the NACF’s democratization. The members of the co-operatives are now able to elect and dismiss the president. Moreover, the government’s control and vigilance of co-operatives was relieved, and members’ autonomy strengthened.

Unlike Japan and South Korea, literature regarding agricultural co-operative reform in Indonesia exposed that regime changes and economic transformation were the primary determinants in village unit co-operative reform. Rifin [48] explained that the development of the village unit co-operatives destroyed the other forms of co-operatives, such as rubber and copra. Moreover, monopolistic practices by the village unit co-operatives also destroyed the clove agribusiness in the country. However, there was no farmers’ movement to urge the democratization of co-operatives. The people in rural areas can only accept the government’s regulations or create other forms of organization, such as farmers’ associations.

Suradisastra [47] and Rifin [48] described that the newly elected president enacted presidential instruction number 18 in the year 1998 on Co-operative Development to encourage the formation of co-operatives, and thus abolished the status of single co-operatives in rural areas given to village unit co-operatives. According to this law, the government encouraged the organization to act as a co-operative per se.

In China, Hu et al. [63] found that the government intervention in agricultural co-operative development, one of which is providing subsidies, attracts many applications to register as a co-operative. Lei [30] confirmed that the increasing number of agricultural co-operatives, regardless of the quality, is one of the indicators of regional development by local government. According to those situations, Hu et al. [63] studied Farmers’ Co-operatives in China: A Typology of Fraud and Failure, and categorized four types of not authentic agricultural co-operatives, namely “shell co-operatives” (the term “co-operative” from the start was simply a name falsely inscribed on a plaque hung on the office door), de facto private agribusinesses (although registered as co-operatives, they are actually private agribusinesses that have market-based transactions with participating farmers), decooperativized co-operatives (initially relatively authentic. Due primarily to market pressures, these co-operatives progressively converted into commercial enterprises), and failed co-operatives (co-operatives that eventually failed for various reasons, including poor leadership, lack of management experience or skills, or hostile external market environments).

Hu et al. [63] conducted research that spans seven years (2009-2016) and covers all of China’s macroregions. Out of 50 case studies of registered co-operatives, the authors found only two that can be considered authentic and successful. In relation to this situation, Zhong et al. [51] portrayed the government wanted to force empty-shell co-operatives and “fake” co-operatives to withdraw from agriculture operations and emphasizing co-operatives standardized development by launching a campaign cleaning up “fake” co-operatives.

Recognition and introspection helped the co-operative, including its owner, to make a decision that would impact organizational activities. Maclachlan and Shimizu [64] found that some co-operatives in Japan plunge into institutional reform while others do not. The variables that impacted the decision consist of local demographic conditions, the ratio of regular members to associate members, local conditions (resource endowments and product-specific market conditions), the presence of proactive agents of change, and farmer organization behind new strategic goals.

Furthermore, Maclachlan and Shimizu [64] concluded that there are many variables that encouraged farmer-members to stay and connected with co-operatives and primary co-operatives with the federation system: a) the co-operative gives farmers what they want: a competitive, stable income stream and a cushion against market-related risks, b) collaboration among parties has been rooted in strong organizational linkages between farmers and the enterprise that respond effectively to competitive price signals and c) market opportunities and the threat of farmer defections led the national federation to adapt to dynamic situations and do better for local farmers.

Cook [36] explained that co-operatives that could adapt in various situations, might pursue the opportunity to regenerate through multiple life cycles (operate continuously). In South Korea, Burmeister [65] concluded that after its initial reform, one of the issues in the future for agricultural co-operatives is the separation of banking and economic services. Burmeister [46] portrayed that since the end of the 1980s, financial service activities become a more critical part of the agricultural co-operative business portfolio. Concerning this situation, Choi [44] found that organizational adaption encouraged the formation of Nonghyup Agribusiness Group Inc. (sales, distribution, and processing of agrifoods, and supplying agri-inputs and machines) and Nonghyup Financial Group Inc. (financial businesses, for example, banking, insurance, investment, and asset management) as the enterprises under the control of farmer members through the NACF.

In Indonesia, since the end of the heavy government intervention era, the agricultural co-operatives have ended up in one of four options proposed by Cook [36]: exit, status quo, reinvention, and spawn. The exit position means that the co-operative no longer exists. Riswan et al. [66] explained that this type of co-operative is generally established only to access the government program. Moreover, the status quo could be divided into two situations: First, it is not conducting its activities anymore but does not exit the business because the organization is still obligated to another party, mainly the financial institution. Second, the agricultural co-operative still runs its activities with lower participation from the members, which impacts the business volume and tends to shrink or stagnate. Third, reinvention occurs when the board of directors has a set of managerial skills to adapt to the institutional changes or the stakeholders of the co-operatives are consistent with their nature to support the farmers by providing agricultural unit businesses. Fourth, spawn is chosen when the government allows the member of the village unit co-operative to form a new co-operative, mainly with the same business line as the “parent”.

In China, Zhao and Yuan [67] exposed that a new type of co-operative has emerged. The new one is relatively different from the existing co-operatives. The co-operatives emerged due to the visit of two groups of Chinese policymakers, academic and co-operative managers to Canada (Canadian Co-operative Association (CCA)). In Canada, farmers successfully established and ran credit co-operatives that operated and controlled by themselves.

Studies concerning institutional history in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China have shown that government intervention is crucial for agricultural co-operatives development, especially during the organizational design stage. This situation differs from agricultural co-operatives in Western countries, which generally formed as the combat power to tackle market failure. Moreover, the Japanese government was the first ruler to enact a law to manage co-operatives, thus bringing early certainty for the stakeholders to follow up within the country. On the other hand, the dynamics of ideology and the unavailability of regulation were factors of the uncertainty for agricultural co-operatives in China.

The government in Japan and South Korea encouraged the federation system, from the national level to the primary co-operative in rural areas, in order to ensure the realization of its goals. Through the system, the government only needs to concentrate on cooperation with the apex organization instead of disseminating its policy to thousands if not thousands of people and co-operatives. Consequently, the cooperation between the Japanese government and the apex organization resulted in the changes of co-operatives to groups with strategic lobbying power. Meanwhile, in South Korea, the authoritarian government ensures that the society obeys the government’s mandate.

In Indonesia, the federation system exists, but it emerged from the initiation of primary co-operatives that wanted the federation at the provincial and national levels to coordinate agricultural co-operative development. However, studies have found that the government is more concerned about organizing primary co-operatives and legalizing the regulation in supporting it. On the other hand, China has various types of agricultural co-operatives, and only Supply and Marketing Co-operatives work in the federation system and are led by the State Council [68].

A review of the institutional history of agricultural co-operatives in four Asian countries also found that the co-operatives can run the multipurpose business unit to cover the various needs of farmers or even the society. Initially, the possibility emerged from the government regulation that gave co-operatives anti-monopoly exemptions, tax exemptions, subsidies, and the chance to distribute various programs by the government. However, when the reformation of agricultural co-operatives occurred, the organization is still running a multipurpose business unit, mainly financial and agribusiness, with the consideration of maintaining the needs of farmers that are not only related to the providing input or marketing the produce but also financing the farm business or agro-industry [44].

Agricultural co-operative reform has occurred because of various reasons, which differ between one country and another. In Japan, conflict of interest emerged among co-operatives stakeholders (farmers and the co-operative, regular members and associate members, and full-time members and part-time members). However, the regime changes and the co-operative declining political power made it possible to reinvent the co-operatives [62]. In South Korea, the regime changes encourage farmers to urge the democratization of agricultural co-operatives [44]. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, a combination of political dynamics and economic transformation stopped the status of village unit co-operatives as single co-operatives in rural areas and created the opportunity for the society to establish a co-operative of their own [47, 48]. Lastly, in China, the issues of fake co-operatives have been discussed and it is empirically proven, the government therefore decided to guide co-operatives standardization [51].

A review of the institutional history of agricultural co-operatives in Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and China emphasized that the four countries have similar situations in terms of government intervention in agricultural co-operative establishment and development. The government encouraged the establishment of agricultural co-operatives to accelerate its sectoral and national programs. Thus, the co-operatives became state agencies. Later, each country’s social, political, and economic situation brings a different trajectory of agricultural co-operatives development.

In Japan, the government used to urge the farmers to join the primary co-operatives, and asked the primary co-operatives to operate within the federation system. Currently, the conflict of interest among stakeholders, economic transformation, the declining political power of Japan’s agricultural co-operatives, and regime changes have made it possible for farmers/primary co-operatives to decide whether to join the co-operative/federation system. In South Korea, the end of the authoritarian era and the continuous farmers’ movement successfully changed the co-operatives from parastatal to co-operative per se. In Indonesia, economic transformation and political dynamics became the primary drivers of agricultural co-operatives reform. Lastly, in China, the government’s desire to promote agricultural co-operative establishment has resulted in some fake co-operatives, and the government turns to guide co-operative standardization.

This manuscript is part of the doctoral research funded by The Indonesian Education Scholarship (Beasiswa Pendidikan Indonesia)

| No | Country | Number of Agricultural Co-operatives | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Afghanistan | 2,429 | [69] |

| 2 | Armenia | 82 | [70] |

| 3 | Azerbaijan | 156 | [71] |

| 4 | Bahrain | not available | not available |

| 5 | Bangladesh | 170,000 | [72] |

| 6 | Bhutan | 71 | [73] |

| 7 | Brunei | 23 | [74] |

| 8 | Cambodia | 1,200 | [75] |

| 9 | China | 2,200,000 | [76] |

| 10 | East Timor | not available | not available |

| 11 | Egypt | 5,435 | [77] |

| 12 | Georgia | 1,500 | [78] |

| 13 | India | 99,547 | [79] |

| 14 | Indonesia | 35,761 | [80] |

| 15 | Iran | 1,800 | [81] |

| 16 | Iraq | not available | not available |

| 17 | Israel | not available | not available |

| 18 | Japan | 584 | [82] |

| 19 | Jordan | not available | not available |

| 20 | Kazakhstan | 2,919 | [83] |

| 21 | North Korea | not available | not available |

| 22 | South Korea | 1,122 | [44] |

| 23 | Kuwait | not available | not available |

| 24 | Kyrgyzstan | 328 | [84] |

| 25 | Laos | not available | not available |

| 26 | Lebanon | 1,238 | [85] |

| 27 | Malaysia | not available | not available |

| 28 | Maldives | not available | not available |

| 29 | Mongolia | not available | not available |

| 30 | Myanmar | not available | not available |

| 31 | Nepal | 10,421 | [86] |

| 32 | Oman | not available | not available |

| 33 | Pakistan | not available | not available |

| 34 | Philippines | not available | not available |

| 35 | Qatar | not available | not available |

| 36 | Saudi Arabia | 63 | [87] |

| 37 | Singapore | not available | not available |

| 38 | Sri Lanka | not available | not available |

| 39 | Syria | not available | not available |

| 40 | Tajikistan | not available | not available |

| 41 | Thailand | 3,211 | [88] |

| 42 | Turkey | 8,173 | [89] |

| 43 | Turkmenistan | not available | not available |

| 44 | United Arab Emirates | not available | not available |

| 45 | Uzbekistan | 872 | [90] |

| 46 | Vietnam / Viet Nam | 21,000 | [91] |

| 47 | Yemen | 427 | [92] |

| 48 | Palestine | 610 | [93] |