2024 Volume 12 Pages 93-110

2024 Volume 12 Pages 93-110

Originally introduced as a regulation to persuade different gene expressions during an organism’s developmental process to display new characteristics through environmental stimuli, epigenetics has become an exciting field of study. Epigenetics, particularly its contribution to plant plasticity in response to the changing environmental pressure, is gaining more attention nowadays. Benefiting from the low cost of the latest next generation sequencing technologies, recent techniques such as whole genome bisulfite sequencing provide epigenome data at a single-base resolution. However, the application of such technology is skewed to model organisms with known genome reference data. Here, we aim to revisit the methylation sensitive amplification polymorphism (MSAP), an indirect technique to analyze the change in DNA methylation level that is cost-effective and applicable for species with no reference genome available or having a large and complex genome. We found that MSAP is a pragmatic approach for application in a wide range of plant species and fields of study. Key steps in MSAP, such as the sequence of primers, primer pair combinations, and data interpretation, are summarized, providing a one-stop beginner’s guidance for evaluating DNA methylation changes.

In genetics, gene activity or function can change due to alteration of the DNA sequence, either by point mutations, deletions, insertions, or translocation. In 1957, Conrad Waddington, a British developmental biologist, proposed a concept that a population (or organism developmental process) can be persuaded to display new characteristics through environmental stimuli. Conrad Waddington’s works hypothesized mechanisms that may control the readout of genes to produce different phenotypes from the same genotype [1, 2]. It is now called epigenetic, meaning beyond or above (epi-) genetic. Epigenetics are chemical marks added to the genomes of eukaryotes either on DNA or histone proteins. The marks are crucial information regarding the accessibility of DNA sequences in particular locations in the genomes. Epigenetic marks on histone protein create a compact or loose chromatin structure. The compact or tightly closed chromatin, known as heterochromatin, limits access to transcription machineries, hence silencing the gene expression. Meanwhile, loose or open chromatin or euchromatin is associated with gene transcription activation.

Another mark is DNA methylation. Methylated nucleotides block transcription factors from binding to a promoter region even though the promoter is located in the accessible euchromatin area, preventing transcription initiation. In the beginning, epigenetics is closely associated with establishing cell fates during the development of multicellular organisms, and like genetics, it can be inherited [3]. Today, epigenetic regulation is considered a highly dynamic process with a critical function in determining vastly different processes in response to external factors, from implicating the development of disorder or disease in animals to phenotypic plasticity in plants [4, 5]. Orchestrated by the interplay between DNA methylation, histone modification, and the presence of non-coding RNA, epigenetics integrates external and intrinsic stimuli to regulate gene expression [6, 7].

Epigenetic information is regulated spatio-temporally, thus mapping the epigenome may help us to understand its biological significance. Benefiting from the low cost of the latest next generation sequencing technologies, epigenome mapping analyses have gained more interest in recent years [8]. For example, chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is a reliable tool for studying epigenetic regulation by DNA-binding proteins such as histone and transcription factors. The whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) exploits the conversion of cytosines into uracil when treated with bisulfite, while methylated cytosines remain unaffected. Epigenome sequencing generates a large amount of data, which provides comprehensive insights into the epigenetic landscape along the genomes. However, mapping reads and integrating these resources into transcriptome data (transcript level or gene activity) presents challenges [9].

Others use a similar technique to random amplified polymorphic DNA or amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) to study a global methylation pattern. Methylation sensitive amplification polymorphism (MSAP) method adopts AFLP principles using methylation sensitive endonuclease enzyme prior to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification. MSAP is still largely used in ecological epigenetics, looking at cytosine methylation state randomly distributed along the genome of unknown sequences [10]. In addition, MSAP is a relatively cost-effective tool and potentially suitable for many research laboratories with standard equipment [11]. Protocol on the MSAP technique was first developed to determine DNA methylation in fungi [12] and later modified for its use in plant species [13]. Briefly, the technique consists of 4 main steps, i.e. (1) genomic DNA extraction, (2) DNA digestion using restriction enzymes, (3) amplification of fragmented DNA by PCR, and (4) fragments analysis. The second and third steps are crucial in the MSAP technique; therefore, most MSAP procedures provide a detailed step-by-step on genomic DNA digestion and PCR. The addition of adapter on digested DNA fragments guarantees successful fragment amplification in MSAP method. However, choosing the most suitable selective primer combination to produce representative fragments for data interpretation is still the most laborious part of this analysis. This review starts with an overview of DNA methylation and is followed by the basic principles of MSAP methods. The methodology section will provide all-in-one guidance for readers who are new to the techniques and interested in utilizing it. Lastly, we highlight MSAP as a pragmatic tool in quantitative epigenetics to study the relationship between epigenetic variation and phenotypic traits.

DNA methylation refers to transferring a methyl group (CH3) onto the fifth carbon position of the cytosine pyrimidine ring, forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC). The addition of methyl group does not interfere with the classic Watson-Crick nucleotide base pairing that existed naturally in DNA [14, 15]. Since then, the role of modified cytosine in cell fate determination through regulation of gene expression has become a main topic in epigenetic regulation [16]. Genomes are organized into a compact chromatin structure by nucleosome. DNA packing by nucleosomes also limits access to DNA-binding proteins that regulate gene expression. In chromatin, regulatory regions, such as promoters, are usually accessible to the transcriptional machinery [17]. A cluster of CG-rich sites predominantly occurs at the promoter region of genes, thus giving its name CpG islands [18]. Several observations also suggest a correlation between nucleosome occupancy, CpG sites, and DNA methylation patterning [19, 20, 21]. It is worth mentioning that while the promoter region of endogenous genes is rarely methylated [22], the mobile transposable element (TE) which can cause genetic variability, is usually inactivated by DNA methylation [23, 24].

Once the methylation takes place, it will be the target of Methyl-CpG-binding proteins (MBP). In turn, the MBP could recruit Histone Deacetylases (HDACs) complexes to deacetylate histone, or MBP-containing Histone Methyl Transferases (HMTs) bind to methylated DNA and subsequently methylate histone tails. The concerted events of MBP, HDACs, and HMTs complexes cause chromatin condensation and, eventually gene silencing [25]. Further, although TE silencing is found in animals and plants to protect the organism from harmful consequences, it is proposed that TE inactivation through DNA methylation plays a more important and complicated role in the plant than the animal [26].

In mammals, DNA methylation almost exclusively occurs at the CG site [18]. The process is catalyzed by a family of DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs). The DNMT1 maintains methylation during DNA replication by binding to newly synthesized DNA and mimicking the DNA methylation pattern from the parental strand. The DNMT3 is called de novo DNMT due to its activity in introducing new methyl groups into naked DNA [27]. In plants, DNA Methyltransferase 1 (MET1) are DNMT1 orthologs. In addition to methylation at the CG site, DNA methylation in plants also occurs at CHG and CHH sequence motifs where H is A, T, or C [28]. Plant-specific Chromomethylase 3 (CMT3) and CMT2 maintain methylation at CHG and CHH sites, respectively. Meanwhile, de novo methylation occurs at all motifs and is controlled by Domains Rearranged Methyltransferases (DRMs) via RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM) pathway.

MSAP is a modified form of the AFLP technique to study polymorphism of methylated cytosine along the genome [29]. In the original AFLP method, genomic DNA is digested with a rare cutter EcoRI and a frequent cutter MseI. The frequent cutter enzyme is then substituted with methylation sensitive isoschizomers restriction enzyme (i.e., HpaII or MspI) in MSAP and keep the EcoRI. Methylation at cytosine can occur either in a single strand (hemi methylated) or both strands (fully methylated) of DNA and at the external or internal cytosine site [30]. HpaII and MspI recognize and digest the unmethylated 5’-CCGG-3’ sequence but show different digestion abilities when methylation occurs at one or multiple cytosines (Table 1). The HpaII will digest at site where the external cytosine is hemi methylated (5’-hmCCGG-3’) but will not if the external cytosine or both cytosines is fully methylated (5’-mCCGG-3’ or 5’-mCmCGG-3’); whereas MspI will digest if the internal cytosine is fully or hemi methylated (5’-CmCGG-3’) but will not if the external cytosine is fully or hemi methylated (5’-mCCGG-3’ or 5’-hmCCGG-3’). Both HpaII and MspI will not digest when the external or both cytosines are fully methylated (5’-mCCGG-3’ or 5’-mCmCGG-3’ or 5’-hmChmCGG-3’), and therefore these two methylation states cannot be distinguished by the MSAP technique [31].

Generally, DNA methylation analysis using the MSAP approach consists of 6 main steps (Fig.1). The analysis begins with genomic DNA extraction from tissue of interest (Fig.1, step 1). Next, two simultaneous restriction digestion is performed in the MSAP method, i.e. digestion of extracted genomic DNA with EcoRI and HpaII (methylation sensitive) and EcoRI and MspI (methylation insensitive) restriction enzyme pairs (Fig.1, step 2). The digestion will result in DNA fragments with different digestion ends (5’-AAT-3’ and 5’-CG-3’ overhang) and fragment lengths (EcoRI-MspI digestion is relatively longer compared to EcoRI-HpaII) [32]. Following enzymatic digestion, specific adapters designed to match with each cleavage end are ligated (Fig.1, step 3) and subsequently amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (Fig.1, step 4). Two consecutive PCR are usually performed in MSAP analysis, pre- and selective amplification. The pre-selective step amplifies the initial digested fragment using primer pairs that anneal each adapter sequence. The product of pre-selective amplification is then used as a template for selective amplification. At this step, the initial amplified fragments are further filtered/selected by PCR using primer pairs with additional selective nucleotide. The selective nucleotides are added at the 3’-end of the pre-selective primer pairs. Lastly, the selectively amplified fragments are visualized by electrophoresis or genetic analyzer instrument (Fig.1, step 5). Methylation events can then be identified by interpreting the visual pattern of amplified fragments (Fig.1, step 6). When two or more samples are compared, for example control and treated plants, pattern of the resulting amplified fragments will allow identification of differentially methylated regions (DMRs) among tested DNA.

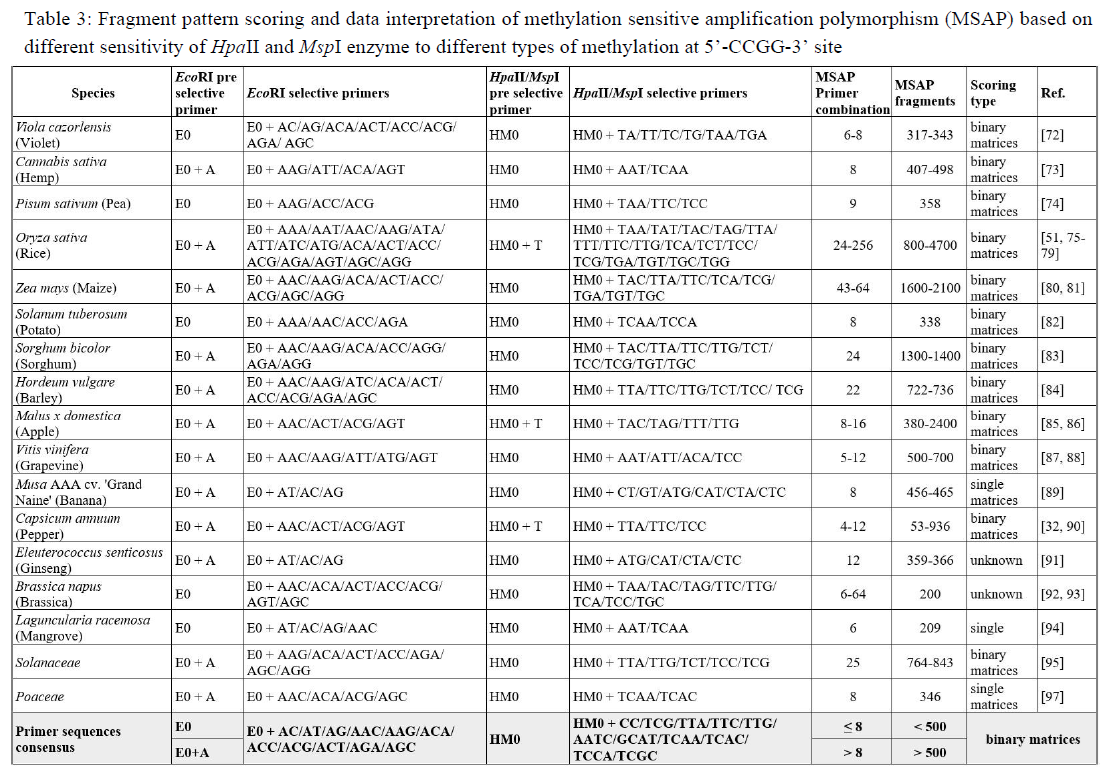

In the original protocol of the AFLP method, Vos et al. [29] provide the structure for adapters and primers, consisting of core and enzyme-specific sequences. In MSAP, the enzyme-specific sequence in the MseI adapter and primer (5’-TTA-3’) is modified to HpaII and MspI cleavage ends (5’-CG-3’) while the core sequence remains the same (Table 2). Primer sequences for AFLP and MSAP are designed to complement the adapter sequence (the strand containing the enzymatic sequence) with additional selective nucleotides that are added at the 3’ ends of the primer. The number of selective nucleotides in each primer can vary from one to four residues, determining the number of amplified fragments produced at the end of the amplification steps. The amplified fragments resulting from the pre-selective step are usually not well separated on gel and will appear as a smear. The addition of several selective nucleotides at the 3’- end of the primer will reduce the number of amplified fragments, producing well-separated fragments on gels, and allowing comparison of banding patterns between restriction enzymes or across the tested sample. For example, pre-selective amplification using EcoRI+A/HpaII-MspI+0 or EcoRI+A/HpaII-MspI+T primer pairs will only decrease the fragments to 1/4 and 1/16, respectively. Subsequent amplification of the pre-selective product, for example, with EcoRI+AT/HpaII-MspI+TA primer pair, will result in 256 times less fragment than the pre-selective. In most MSAP practices, the combination of primer pairs is customized to suit the genome size and the number of fragments to be analyzed. In general, EcoRI+2/HpaII-MspI+3 is commonly used for small genome sizes; meanwhile, EcoRI+3/HpaII-MspI+3 or EcoRI+3/HpaII-MspI+4 is preferred for larger genome sizes [33]. Adding selective nucleotides is done randomly, so for example, selective amplification steps that add two selective bases on the 3' end of each primer can result in a maximum of 256 (16 × 16) possible primer combinations. However, performing PCR analysis for all probable primer pairs could prove to be a time-consuming and expensive process. Table 3 showcases the differences in the quantity of primer employed to study the occurrence of DNA methylation in various plant species. We noted that most studies listed in Table 3 conduct initial experiments to determine the most suitable primer pairs. Some combinations of primer pairs were commonly used in these studies and we summarized them into a list of ‘primer sequence consensus’. In the case that testing all potential primer combinations is incompatible with a researcher's experimental design, the primer sequence consensus may be worth considering. Further, with advances in computational and artificial intelligence deep learning for biological applications, developing in silico tools to design the most suitable primer pair combination will improve MSAP output. This is well established in similar DNA fingerprinting technique such as cDNA-AFLP [34, 35]. The available in silico AFLP allows to reduce the amount of primer pair combination without sacrificing the data coverage [36, 37]. Building upon the success of in silico AFLP, bioinformatic modeling for MSAP data collection and analysis can lead to the production of more precise and insightful methylation data, especially in organisms with sequenced genomes.

The final step of MSAP is visualization of amplified fragments and data interpretation. Traditionally, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis provides a reasonable resolution of fragment separation. Nowadays, a microcapillary-based electrophoretic cell such as those used in a Bioanalyzer™ system can provide both convenience of usage and maximum resolution of the banding patterns [38]. Once visualized, the resulting amplified fragments from EcoRI-MspI and EcoRI-HpaII digested DNA are compared and then converted into scores. Two main scoring approaches are binary and single scoring (Table 4) [39]. Binary scoring where the presence or absence of DNA band from each electrophoresis lane corresponds to EcoRI-MspI and EcoRI-HpaII digestion into ‘1’ or ‘0’, respectively. The single scoring transforms amplified fragment patterns EcoRI-MspI and EcoRI-HpaII into one value. A score of ‘1’ represents the presence of methylated cytosine, i.e. presence of DNA band in EcoRI-MspI and EcoRI-HpaII digestion reaction (+/- or -/+ band pattern), otherwise the score is ‘0’ (+/+ band pattern).

Theoretically, there are eight possible cytosine methylation occurrences in double stranded 5’-CCGG-3’ site that can be classified into four methylation types using the binary scoring system. Type I is non-methylated cytosine which is indicated by the presence of fragments in both EcoRI-MspI and EcoRI-HpaII digestions. Type II is the hemi methylation at external cytosine when amplified fragments are only detected in EcoRI-HpaII digestions. Type III is methylation at internal cytosine (either hemi or fully) when fragments are present only in EcoRI-MspI digestions. Type IV represents full methylation at the external or both cytosine (5’-mCCGG or 5’-mCmCGG or 5’-hmChmCGG) and since this type of methylation will not result in any amplified fragment, determination can only be made when DNA methylation polymorphism is detected when comparing at least two samples (Table 5), i.e. presence of DNA band in one sample (1-1 or 1-0 or 0-1) and complete absence in the other sample (0-0) or vice versa. Lastly, the percentage of the polymorphic loci can be determined by dividing the total number of DNA bands representing methylation events (1-0, 0-1, 0-0 band patterns) by the total number of DNA bands detected on the gel electrophoresis.

Perez-Figueroa [31] published a ‘msap’ R package for analyzing differentiation in MSAP assay. The program was designed to be user-friendly and suitable for researchers with minimal command line experience. It is built to calculate the number of methylated loci, determine loci susceptible to methylation (methylation polymorphisms), the class or type of methylation observed, and visualize the report as plots. It is a resourceful tool that will help researchers assess MSAP results quickly. As of this publication, the package has been removed from CRAN (http://cran.r-project.org/) repository. However, the package is still available in CRAN archive (https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/msap) for manual retrieval and instalment into R studio. Access to source code, documentation, and instructions for downloading the latest version can also be found on ‘msap’ GitHub page (https://github.com/anpefi/msap).

Other than MSAP, detection of 5mC can be made by bisulfite conversion and affinity capture of methylated DNA followed by sequencing [40]. These methods allow both genome-wide and locus/gene-specific identification of methylation events. Before the next-generation sequencing era, the number of research utilizing whole genome bisulfite sequencing and MSAP techniques to analyze DNA methylation was comparable (Fig.2). The reduced cost of the high throughput sequencing technologies and rapid improvements in bisulfite conversion method facilitated the significant increase of genome-wide DNA methylation analysis with a single-base resolution. While sequencing-based DNA methylation detection is a powerful technique, it does have some drawbacks. The complexity of the procedure can affect the completeness conversion of unmethylated cytosine in the bisulfite conversion method [41]. In the affinity capture-based method, the quality of anti-5mC antibodies can cause cross-reactivity or affinity bias toward the hypermethylated region [42]. The generation of low sequence diversity in short-read sequencing can limit the accuracy and resolution of the analysis [43]. Further, connecting DNA methylation data at single-base resolution (the methylome) with gene expression (transcriptome) poses quite a unique challenge. Mapping sequencing reads accurately within highly repetitive and complex regions of the genome makes high-quality reference genome data and bioinformatics analysis skills to be indispensable [44].

To date, the MSAP approach is still a useful alternative high-throughput analysis of differentially methylated CpG sites in plants with large, complex, and highly repetitive genomes [45, 46]. It is a practical technique used in study with a large sample size such as in population study [11]. First, MSAP method is simple, utilizes standard molecular reagents and equipment (cost effective), and sample processing to results can be less than a week (time efficient). Second, despite its simplicity the method still enables parallel and direct analysis of DNA methylation sites across the genome (high throughput). Third, application is not limited by availability of genome reference, which is suitable for application in applied science, e.g., quantitative epigenetic study looking for relationship between phenotypic variation with environmental dynamics.

Several studies that applied the MSAP method successfully demonstrated an association between the alteration of plant DNA methylation level and the phenotypic trait. A population study comparing the wild and cultivated populations of watercress (Rorippa nasturtium var. aquaticum L.) reported that genetic and epigenetic characterization can discriminate the wild and cultivated species [47]. The watercress study further notes that while genetic diversity was absent, epigenetic mediates phenotypic variation or plasticity to cope with environmental pressures [47]. Studies of plant epigenetic dynamics during exposure to abiotic stressors generally observed an association between changes in DNA methylation level and its implication on plant growth and development. Studies in rice, rapeseed, and foxtail millet exposed to salinity stress conditions all reported a decrease in methylation levels (hypomethylation) observed in tolerant compared to sensitive cultivars [48, 49, 50]. Further, a study in rice reported that in the tolerant genotype, most methylation changes were reversed upon removal from the stress condition and the remaining differentially methylated loci are transgenerational inherited [51, 52]. Similar trends were also reported in drought stress [53, 54] which may indicate that the DNA methylation regulation during osmotic stress may be universal.

Upon biotic stress, DNA methylation pattern in plant is also suggested to play key roles in determining resistance [55]. For instance, differential DNA methylation in wheat showed that upon infection by Puccinia triticina, susceptible cultivar had a large number of hypomethylated genes and relatively fewer hypermethylated genes [56]. Whole genome DNA methylation analysis by MSAP has been reported in tomatoes infected by tomato yellow leaf Sardinia virus [57], rice infected by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae [58], chickpea infected by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris [59], and banana infected by F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense tropical race 4 [60]. The results of those studies indicated that response to pathogens is characterized by DNA hypomethylation in chickpea and rice [58, 59]; by DNA methylation polymorphism among stress response genes in tomato, chickpea, and banana [57, 50, 60]; and by transcriptome reprogramming in rice and banana [58, 60].

The transgenerational inheritance of epigenetic markers is a promising avenue in crop improvement of important agronomic traits. Generating desirable characteristics by inducing DNA methylation within a single generation of crops that persist in its progeny is a promising potential to complement the existing plant breeding process [61]. Polyploidization and hybridization are breeding techniques that aims to create new species with improved traits compared to their parents (also known as heterosis). Nonetheless, disadvantages such as less vigor or abnormal organisms due to increased genome complexity and abnormal genome segregation during meiosis and mitosis are also reported in polyploid or hybrid organisms [62, 63]. A study in apple demonstrates that autotetraploid clones have a higher DNA methylation level compared to its diploid parental, which is associated with development abnormalities such as premature dormancy, observed in the autotetraploid clones [64]. A study investigating methylation changes in allopolyploid Brassica showed higher methylation in the sterile allodiploid (AB genome) than fertile allotetraploid (AABB genome) but heterosis was exhibited by the allotetraploid clones [65]. Lastly, in vitro tissue culture is commonly used in plant breeding programs and is also known for inducing epigenetic variabilities in the regenerants [66]. All these studies demonstrate that by understanding the effect of DNA methylation on plant phenotype, breeders can identify and select desirable traits for crop improvement. However, accuracy can only be achieved by studying a large population of plants and in the case of transgenerational inheritance following up the stability of traits over generation is inevitable.

It is important to note that no method fits all in DNA methylation study, limitation includes research goals, available resources, and budget constraints. Utilization of whole genome bisulfite sequencing [67, 68] or the most current DNA methylation detection using Oxford Nanopore Technology [69] allows single-base resolution data. High-resolution DNA methylation data can be more suitable if a comprehensive understanding of DNA methylation patterns in plant traits is sought. For example, a recent investigation delved into the degradation of pesticides in rice, revealing a notable reduction in the DNA methylation at CpG island upstream key gene in the jasmonate-signaling pathway, specifically CORONATINE INSENSITIVE 1a [70]. For profiling epigenetics in a cost-efficient manner, especially in a large set of samples or organisms with no reference genome, the MSAP method will be suitable for conducting early-generation testing or fast phenotyping. This can help in maximizing the benefits of the MSAP method before complementing it with the sequencing approach, which can be more expensive and time-consuming [71]. By adopting this approach, researchers can achieve a better balance between cost and accuracy while obtaining reliable results.

Epigenetics in plants is one of the key regulators of cell plasticity. Being sessile organisms, plants also rely on their epigenetics to fine-tune phenotypic responses towards biotic and abiotic stresses, which is important in the face of climate change. ChIP-seq assay provides insight into the dynamic of chromosome remodeling. However, this method is unable to capture DNA methylation data, ignoring inaccessible DNA regions in the euchromatin areas. Coupling ChIP-seq and WGBS analysis is considered the gold standard in epigenetics studies. The combination of high-resolution data of DNA regions in nucleosomes and DNA methylome will give a complete view of epigenetic state in an organism. However, a more cost-effective method compared to the sequencing approach will be more beneficial for studying epigenetics dynamics that change depending on the environmental conditions or developmental stages. Thus, we propose MSAP as a considerable method for high-throughput assessment of DNA methylation changes in plants. The technique enables parallel and direct analysis of DNA methylation across the genome. For the same species, MSAP could be performed many times with identical protocol once the primers and adapters sequences are established.

Furthermore, considering the complexity of methylation events in plants, such as large genomes with many repetitive sequences and methylation at non-CG sites (CHG and CHH), choosing a relatively simple and cost-effective method is still preferred. MSAP is limited to specifically identifying methylation in CCGG sites. However, considering CCGG sites are primarily located in a promoter region and thus regulate the expression of associated genes, information on methylation levels or changes at CCGG sites is valuable. The number of epigenetic studies still utilizing MSAP shows the versatility of the technique, especially its application in model and non-model plant species or experiments with large sample sets. Collectively, customized protocols in many species will encourage more research or usage as quality control steps in breeding efforts to adopt the MSAP technique. The generated data are then expected to be the basis for building a database associating phenotypes with global DNA methylation status. For instance, the database will provide DNA methylation patterns found in plants with superior traits. Conforming their heritability would be important for developing breeding strategies based on these. However, if the focus is on improving phenotype within one generation, such as inducing hypo-/hypermethylation, then it is more important to describe the inducer(s).

Nevertheless, there are some outstanding questions of how to explore DNA methylation to improve plant phenotypes especially under the condition of biotic and abiotic stresses. How long is the DNA methylation pattern retained in a population with desired phenotypes? Is the pattern as temporary as the presence of the inducer/stress? If the pattern is heritable, then how many generations until an inducer is again required to bring out the DNA methylation pattern? If these questions have been answered, then the utilization of MSAP will be more routine and diverse.

This article is part of the DH postdoctoral fellowship research financially supported by ITB research grant through P3MI program 2022 at Plant Science and Biotechnology research group of School of Life Sciences and Technology, Institut Teknologi Bandung.