2021 Volume 9 Pages 143-156

2021 Volume 9 Pages 143-156

As the demand for local products increases, there has been a call to promote sago starch (Metroxylon sagu Rottb.) at the regional level in Indonesia. In this study, we examine the current status of the sago supply chain and its role in promoting rural development. Our study reveals the weak bargaining position sago farmers have due to inefficiencies in the sago supply chain and lack of market information. Furthermore, we also point out the direction in which future actions should be taken as guidelines in order to achieve a high level of efficiency along the sago supply chain. In particular, we highlight farm production management, logistical systems, agronomy, and knowledge and information as key dimensions of sago supply chain in the context of rural development.

Sago is a starch obtained from the trunk of sago palm (Metroxylon sagu Rottb.), a tropical crop of Southeast Asia, Papua New Guinea, and Solomon Islands that grows between latitudes 10 degrees north and south of the equator [1, 2]. It has been recognized as one of the oldest plants consumed by human beings [3]. Sago was first mentioned in the 13th century by Marco Polo [4] and was described by Alfred Russel Wallace in the 18th century as an important food commodity along with rice and millet [5]. It is also considered the only crop that can grow on marginal land and can endure intense insolation, typhoon-strength winds, and prolonged flooding [6,7]. Recently, sago starch has become an important raw material for utilization in various industries [8, 9] with the main producers being found in Sarawak of Malaysia and Indonesia.

The majority of sago starch in Indonesia is produced by smallholders, accounting for 75% of total production in 2017 [10]. For them, sago is not only seen as food but also a functional commodity because they can utilize the stem bark and leaves to construct walls, floor, and roof thatching for houses [11]. It is also a commodity with economic value that contributes to poverty alleviation and a source of saving because sago palm can be harvested anytime whenever farmers need money [12]. Currently, the Indonesian government is encouraging food industries to substitute 10% of imported wheat flour with sago starch to support sago-based industries under a cooperation agreement, Development of Local Starch Utilization as a Raw Material for the Food Industry. The replacement of imported wheat flour with sago starch is expected to increase in the future and produce up to Rp 2.4 trillion (US$ 170 million) of benefits annually [13] and increase sago farmer's income in Indonesia. However, it is observed that sago-based industries have stagnated due to low performance in the production process, lack of market penetration, and lack of interconnectedness both upstream and downstream [14].

We examined the degree to which the stagnation is due to the poor performance in the sago supply chain. However, there have been no empirical studies regarding the efficiency of the sago supply chain in Indonesia. This is because sago supply chain performance by smallholders is difficult to measure due to its complexity and dynamic characteristics. Thus, the present study is considered essential in order to provide a foundation for selecting the most suitable strategies to minimize problems in the supply chain. This review starts with an overview of the geographical flow of sago products and characteristics of the smallholder supply chains in both the western part of Indonesia (Riau) and the east (Southeast Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua). It then focuses on identifying inefficiencies in the sago supply chain before turning to the possibility of improvements from the perspective of smallholders. Finally, we summarize conclusions and recommendations for further studies.

A concept of the supply chain is defined as an integrated process in which various elements (i.e., suppliers, manufacturers, distributors, and retailers) work together in the creation and distribution of products for consumers [15, 16, 17]. Understanding supply chain efficiency is a major pathway for smallholders regarding the assurance of better income, improved food security and the promotion of rural development. In order to examine the nature of the sago supply chain and its integration with rural development, we apply a scoping review in this study. The review presents the reasons why the sago supply chain in Indonesia has not been efficiently developed so far.

Two main subjects (sago palm and supply chain) have been selected in this review, with subtopics that reflect each subject. For the “sago palm” subject, the keywords included in our search were “sago starch”, “sago starch supply chain”, “small-scale sago industries” and “sago processing”. Meanwhile, for the “supply chain” subject, the keywords used included “food supply chain”, “supply chain efficiency” and “sago starch supply chain”. The search was conducted using two online databases restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles, books, and book chapters. In addition, other relevant sources were identified through additional records such as reports, theses, and dissertations, published in both English and Indonesian. The geographical restriction was applied to articles related to the “small-scale sago industries” subtopic, which focused on small-scale sago industries in Indonesia. Meanwhile, the time restriction was applied to articles related to the “supply chain” subject, which focused on articles published from 1997–2019. Identified sources pertaining to our search were then screened via title to eliminate articles that were duplicates. Articles that were irrelevant to our search were then eliminated upon reading them. Finally, a total of 62 studies were then obtained for this paper. In addition to the review, we also provided an insight to construct a distinct, informed perspective of the sago supply chain and how its efficiency can be improved.

Three types of sago palm products that are commonly found in the market of Indonesia: wet sago starch, dried sago starch, and roasted sago (Figure 1). Wet sago is raw starch extracted from the sago palm with 35–45% water content [18]. A traditional extraction method by hand or with simple tools is used by smallholders to produce wet sago. A sago log is rasped by a rasping machine, then compressed by foot or hand as they add water; the water carrying the liquid starch is then passed through a sieve into a suitable container. The liquid is left overnight and wet starch that has settled at the bottom of container is ready to be collected [19]. The second type of sago product, dried sago starch, is produced by drying wet sago, mostly under the sun, reducing the water content to 12–15% [18]. Our preliminary estimation, calculated from records of the Directorate General of Estate Crops and reports from Cirebon Port, show that the distribution of sago starch in Indonesia is mainly focused on the domestic market. That accounts for 97.3% of total production, with wet sago distribution for the domestic market (58.3%) being larger than that of dried sago (41.7%). On the other hand, dried sago is preferred by the international market, accounting for 99.8% of total exports. The last product, roasted sago, is made by putting wet sago into a heated clay mold for 15–20 minutes, resulting in a water content of 12.4% or less. Roasted sago is hard and tasteless, so it is dipped into tea or coffee before being eaten. In Indonesia, roasted sago is called by different names in different places, such as sagu kotak, sagu lempeng or sagu ambon. In this paper, we use the term of “sagu kotak” as it is called on Java Island.

Figure 1: Sago palm and its products. (a) Sago palm in its natural habitat. (b) Wet sago packed in tumang (baskets of sago leaves) being ready to be sold in the local market. (c) Dried sago found in the local market of Java island. (d) Roasted sago (sagu kotak) sold on Java island.

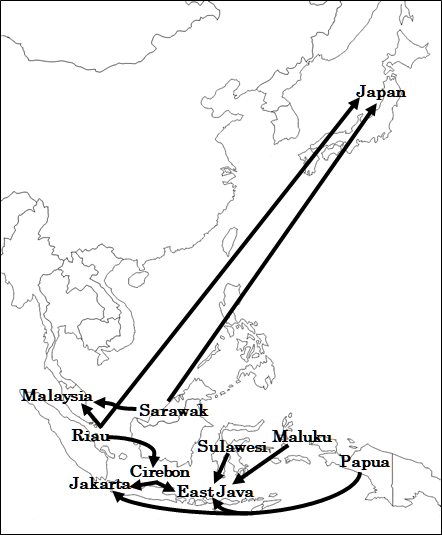

Sarawak and Indonesia are considered the world’s major commercial sago suppliers (Figure 2). In Sarawak, about 41,000–51,000 tons of refined sago were produced annually from 2008 to 2014 and mainly sold to West Malaysia and Japan [20]. Meanwhile, total sago exports from Indonesia to Malaysia in 2017 amounted to 7,095 tons with a total value of US$ 853,631 [10], mainly from Riau due to geographical advantages and high production. Based on Japanese Trade Statistics, about 4,032 tons of sago starch from Indonesia was imported to Japan in 2017, which is mainly from private sago estates in Riau [21]. In Japan, sago starch is used as dusting flour for noodles, dumpling skins, starch sugar and dextrin. Recently, sago starch has been promoted as a gluten-free and non-allergenic food [22].

Riau is also considered the largest sago starch supplier to the domestic market in Indonesia with Java Island as the main market. Dried sago from Riau is distributed to Cirebon, Java for further processing; making glass noodles or for redistribution to other regions such as Jakarta and East Java (Figure 2). Data from the Cirebon Port shows that between 74,895 and 86,167 tons of dried sago starch was moved from Riau to Cirebon annually from 2014 to 2018. Other important sago suppliers are Sulawesi and Maluku. A total of about 2,500–4,700 tons/year of sago starch were produced, mostly in South Sulawesi and Southeast Sulawesi, from 2015 to 2017 [10]. Meanwhile, the main product from Maluku that has been successfully marketed to Java is roasted sago. It is used as the main ingredient of sago pudding, a popular dessert in East Java. Unlike Riau, where large private estates and sago mills exist, Sulawesi and Maluku are considered small-scale sago producing areas.

Figure 2: Geographical flow of sago products from major supply areas to major demand areas and foreign markets

Papua has been considered as a self-sufficient sago production area, where the sago mostly grows wild and is managed by local rules established by custom. A total of between 28,200 and 66,500 tons were produced by Papua annually from 2015 to 2017 [10]. Sago is processed traditionally for self-consumption together with sago weevil and mushroom. In Papua, there are two large sago companies: ANJ Agri Papua and state-owned forestry enterprise (Perhutani). Dried sago production from ANJ Agri Papua is reported to have grown strongly from 1,894 tons to 2,781 tons in 2019 [23] with Jakarta and Surabaya as their main markets. Meanwhile, the progress of Perhutani to this time is still unknown.

Table 1 presents the sago supply chain characteristics of wet sago, dried sago, and sagu kotak in Indonesia. Based on the product durability, wet sago has a short shelf life with maximum storage of no more than 2 months [24]. The supply chain distribution of wet sago is mostly short with a direct transaction between processor/sago mills and consumers, as seen in Riau, South Sulawesi, and Papua. This is because the distance to market is mostly short, typically to the neighborhood and local market, which is suitable given wet sago’s rapid deterioration. It was also revealed that Riau exports wet sago to Malaysia, but the market distance is considered very short (4 hours by ship), so it does not affect the quality of the wet sago product. A different situation is observed in Southeast Sulawesi. The market distance is considered long because it needs 6–7 days to reach Java. Further processing such as rewashing and repackaging are performed to maintain the quality and slow the deterioration of wet sago in this case.

On the other hand, dried sago and sagu kotak have a long shelf life because it may last for years. In fact, a study showed that sagu kotak has exhibited high durability during transportation with no signs of spoilage [24]. The distribution channel of dried sago and sagu kotak can be classified into medium and long with a minimum risk of deterioration. Our interview with resellers in Java also revealed that dried sago has better long-term durability than tapioca and wheat flour, which makes it suitable for long distribution.

4.2 Leading actors in the sago supply chainAccording to our investigation, the market linkages of sago production in Indonesia can be classified into the following categories: (1) farmer to the domestic trader, (2) farmer to the consumer in the food industry, and (3) farmer to the exporter. Those supply chain systems are indirect, relying on intermediaries to perform most distribution functions. Therefore, intermediaries such as collector/middleman, exporter, cooperative, distributor agent, wholesaler, and retailer are the main actors in the sago supply chain rather than the farmer.

We also noted that sago farmers in Riau, the west part of Indonesia, operate differently from farmers in the east part of Indonesia such as Southeast Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua. The Riau farmers focus on cultivating and harvesting the sago palm, then sell sago trees to toke (the local name for the collector) or sago mills. Sago trunks/logs bought by the mill are then processed into wet sago or dried sago. Meanwhile, sago farmers in the east part of Indonesia are associated with extracting the starch from sago trunks and are therefore sometimes identified as a “processor” in some studies [14, 19]. We assume this difference between west and east is due to the existence of sago mills and the cultivation culture of farmers in Riau, which do not favor starch production.

Although a partnership between large private companies and sago farmers has not been established [25], sago cooperatives exist in Riau. Koperasi Harmonis is a sago cooperative founded in 1973, which aims to facilitate distribution and shipment of dried sago starch from small-scale mills in Riau to Java [26]. It is considered to have a positive impact due to its ability to garner profits from distribution, provide good services to its members, and the extensive support it receives from the government.

4.3 Payment flow and information flowIn the supply chain, the product generally flows downstream and payment flows upstream, while information flows in both directions [27]. The payment for sago starch is generally on a cash basis, especially when the purchase takes place in local markets. The consumers pay directly in cash upon receiving the sago product from a retailer or collector. Cash transaction is also used by farmers to sell sago trees or sago starch because they need cash for production. Meanwhile, the information flow in the upstream sector is related to the availability of sago trees, maturity, production capacity, and price. In the downstream sector, information is exchanged regarding order capacity, delivery schedule, price coordination, and invoices. The movement of information is important because it helps to support supply chain activities. It should be noted that the relationship in the wet sago distribution is based on mutual trust and ordering is usually done by phone without any explicit contract. This is because the relationship between farmers and middlemen is strong that it creates long-term transaction. Meanwhile, an explicit contract for dried sago is established in South Sulawesi where producers and retailers openly discuss and coordinate price offers together [19].

| Location | Product | Product durability | Supply chains | Distribution channel | Market distance | Leading actor |

| Riau | Wet sago | Short | I. Sago farmer → Collector (toke) → Sago mills → Exporter Sago mills in Malaysia | Medium | Near (4 hours) |

Collector, exporter |

| II. Sago farmer → Sago mills → Glass noodles and other food factories | Short | Near | Sago mills, glass noodles and other factories | |||

| Dried sago | Long | I. Sago farmer → Collector (toke) → Sago mills → Cooperative/ individual distributor → Distributor agent in Java → Wholesaler → Retailer → Consumer | Long | Far (4–5 days to Cirebon and 2 days to East Java) | Distributor agent, cooperative, wholesaler | |

| Southeast Sulawesi | Wet sago | Short | I. Sago farmer/ processor → Collector → Retailer → Consumer | Medium | Near (local market) |

Collector |

| II. Sago farmer/ processor → Collector → Distributor agent in East Java → Consumer | Long | Far (6–7 days) | Collector, distributor agent | |||

| South Sulawesi | Wet sago | Short | I. Sago farmer/ processor → Consumer | Short | Near (neighborhood) | Sago farmer |

| II. Sago farmer/ processor → Collector → Consumer | Medium | Near (local market) |

Collector | |||

| III. Sago farmer/ processor → Collector → Retailer → Consumer | Medium | Near (special market) | Collector, retailer | |||

| Dried sago | Long | I. Sago farmer/ processor → Dried sago producer → Retailer → Consumer | Medium | Near (souvenir shop and modern market) |

Dried sago producer, retailer | |

| II. Sago farmer/ processor → Dried sago producer → Distributor agent outside South Sulawesi → Consumer | Long | Far (4–7 days) | Dried sago producer, distributor agent | |||

| Maluku | Sagu kotak | Long | I. Sago farmer/ processor → Sagu kotak producer → Wholesaler → Retailer → Consumer | Medium | Near (local market) |

Wholesaler, retailer |

| II. Sago farmer/ processor → Sagu kotak producer → Collector → Distributor agent in East Java → Wholesaler Retailer Consumer | Long | Far (7days) | Collector, distributor agent, wholesaler, retailer | |||

| Papua | Wet sago | Short | I. Sago farmer/ processor → Consumer | Short | Near (neighborhood) | Sago farmer |

| II. Sago farmer/ processor → Collector → Consumer | Medium | Near (local market) |

Collector |

The collector, commonly referred to as the middleman, plays an important role in the sago supply chain. In the rural area, the collector goes to the village and buys sago trees when they are still immature. This advance payment is commonly referred to as the ijon system in Indonesia. Most farmers in Riau sell sago trees to the collector even though the price is lower than if they sell it directly to sago mills. The same situation is also observed in Papua where the collector acts as the sole buyer in the local market. According to a study, a farmer losses profit up to 50% if they sell a sago tree to a collector instead of directly to sago mills [26]. In addition, the collector of wet sago in South Sulawesi can obtain a profit margin of 41.8% without any extra value addition [19].

There are several reasons why farmers depend heavily on middlemen: a) the middlemen offer quick cash to the farmer and b) long-term connections between farmers and middlemen, including middlemen buying the product of poor quality in bulk and providing no-interest loans without a contract. A study in Southeast Sulawesi indicated that the collector provided an advance payment for sago operation and a non-interest loan without an actual contract; as a result, the farmer feels obligated to sell sago to them [28]. We noted that the presence of the ijon system has advantages and disadvantages. For sago farmers who do not have enough capital, advance payment can help them obtain cash to run their sago operation. For the collector, this arrangement is useful to secure the supply of sago. However, it is also noted that this system usually leads to a weak bargaining position for sago farmers as it makes the farmer a price taker instead of price maker.

5.2 Loss and wastage in post-harvest practicesAccording to a study, the loss during harvesting operations may reach 20% due to sago starch left in the stump and top of felled trunks, and further loss occurs if the trunk is allowed to deteriorate before the rasping process is completed [24]. Furthermore, sago starch produced by farmers, especially in the eastern part of Indonesia, is extracted from the pith of sago palm using traditional methods that are inefficient and labor-intensive, resulting in significantly lower yields and higher production cost. The traditional extraction produces a productivity loss of between 25%–41% [8], although others have reported that extraction loss is about 50% [29].

In addition, liquid and solid waste generated during the extraction process is considered the largest cause of starch loss. Several studies have observed that sago waste still contains 30–65.7% starch [28, 29]. Liquid and solid waste are then disposed of around the production unit, contaminating the environment and water sources. It is estimated that at least 20 liters of wastewater is released into the environment for every 1 kg of starch produced [32]. A study in Riau stated that sago waste has not been utilized and has been discharged into the sea without any prior treatment [25]. A similar situation is also reported in the eastern part of Indonesia [19].

Since wet sago has short durability, the rapid post-harvest perishability of sago starch results in financial loss due to quality-related price reduction. In addition, wet sago is mostly packed in tumang (baskets of sago leaves), which hastens deterioration. Inadequate post-harvest facilities also discourage farmers from holding products over time, prompting them to sell sago products as quickly as possible [28]. Our observation in the local market also revealed that middlemen and retailers prevent physical deterioration of wet sago by wetting the starch with water and removing discolored parts or microbial contaminated spots. For dried sago, the drying process is done traditionally by exposing wet sago to the sun. Therefore, the rainy season (November to March) represents a major problem for the small-scale sago industry. Utilization of traditional sun drying method is also considered cheap but the final product still contains a high moisture content. This can cause a high loss in the weight of dried sago during shipment, for example the total weight of dried sago arriving in East Java was only 90% of the original weight. Further study showed that a dried sago producer in South Sulawesi suffered a financial loss of over 59% due to the changing color of dried starch, which accounted for 86.4% of the total quantity of production [33].

5.3 Logistical performanceIt must be noted that the supply chain for sago products mostly operates in the context of small-scale production in rural areas with limited access to logistical systems. The long-chain and broad distribution of sago starch leads to higher prices without any extra value-adding. In fact, the sago supply chain is heavily influenced by the availability and quality of infrastructure such as roads, ports and transport networks. Research in Papua showed that almost half of the production cost is used for transportation due to poor physical infrastructure, which affects the income of farmers [34]. In Maluku, farmers are hesitant to operate in remote areas with poor infrastructure because of the high operational costs that entails [35]. Furthermore, our interview with transportation agents in Java also indicated that long-distance distribution via sea transportation is the most challenging due to bad weather and unreliable infrastructure. Those might impede the delivery and create storage problems, which affects the quality of sago starch. Increased prices are unavoidable because the middlemen and distributors need to pay handling and transportation costs, bear the risk for physical deterioration of the product, and make a profit while helping to give consumers easy access to sago products. Consequently, final consumers need to pay extra, while small scale farmers receive a small profit.

5.4 MarketingMarketing contributes to the improvement of livelihood because it can significantly increase small-scale farmers’ incomes. In addition, better market demand would be addressed properly with better relationship between actors in the supply chain [34, 35]. On the other hand, the new market systems often expect larger supply volumes, favoring collectors distributing sago products in bulk and providing sustained quantity. As middlemen regularly purchase sago in large volumes, they can influence the market price of sago starch.

Quality is another important factor that affects the consumer’s decision to buy sago products. A study showed that farmers in South Sulawesi believe that wet sago is more profitable than dried sago although, in reality, dried sago has average added value seventeen times more than wet sago [19]. Furthermore, the quality of dried sago starch in South Sulawesi is still far below an acceptable standard for edible sago starch. The starch is yellowish-white with a distinctive odor and the producer does not know the acceptable standards for edible sago starch. In addition, there is no control mechanism to ensure the safety and quality of sagu kotak due to reliance on the traditional production method. In fact, a wholesaler in Surabaya remarked that the color and size of sagu kotak are not uniform, which sometimes makes it difficult to sell.

Poor access to markets is also a major problem in rural area. Farmers mostly do not have a strong connection to the market and lack access to finance. Hence, dependency on middlemen is high because through those middlemen, farmers do not need to think about networking and budget expenses to advertise their product. In addition, farmers face significant challenges to participate in new marketing opportunities given their small land areas, scattered production units and small-scale production especially in the eastern part of Indonesia. In Papua, for example, the community can only access natural products in their customary or hamlet area [38] resulting in limited production quantity.

5.5 Limited knowledge and access to informationSago farmers generally face various difficulties in developing their businesses, which push them further towards the limits of survival due to their inadequate knowledge and limited access to information. However, farmers in reality only rely on buyers’ information, which cannot help them make a profitable decision [28]. Furthermore, the low level of education of farmers affects the ability of the community to manage the financial aspect of sago production [38].

A study in South Sulawesi showed knowledge and information positively correlates with the participation of a farmer to cultivate sago [39]. However, in practice, sago production has traditionally been managed with little or no attention to crop farming systems. In fact, farmers in the eastern part of Indonesia consider sago palm to be a forest plant that is grown naturally, resulting in limited agronomical knowledge which negatively affects the sustainability of sago production. If the rate of harvesting is higher than the rate of growth, sago palm might vanish in the future since it takes 8–10 years for sago palm to reach maturity [40].

On the other hand, the transplantation of suckers is commonly done by farmers in Riau for sago palm propagation. Although sago palm can grow without fertilizer, huge losses can occur due to limited knowledge, resulting in the low quality of available suckers, damage to suckers by insects, and poor management during transportation [40]. They also stated that the survival rate of sago seedling declines as the storage period lengthens, with the survival rate for suckers reportedly around 60% after 3 weeks. In such cases, the buyer needs to pay 67% over the cost on account of the 40% seedling loss (i.e. for 100 sago trees, 167 seedlings must be provided).

Furthermore, another main challenge in commercializing sago in Indonesia is the applicability of the technology for small-scale production [41]. Sometimes, the application of technology for post-harvest is constrained by the high cost of technology acquisition and high operational costs. A case in Papua showed improvement of technology through upgraded rasping machines and chainsaws resulted in overproduction which led local farmers to stop selling sago palm trees, as they wanted to secure sago palm trees for their subsistence needs.

Inefficiency is evident in the current sago supply chain in Indonesia, with high production costs, losses in production, and low supply chain performance leading to higher prices for consumers and less income for the farmers. An efficiency curve is adopted from Krajewski et al. [42] to indicate a trade-off between costs and supply chain performance for the current sago supply chain design if it is operated as efficiently as possible (Figure 3). To increase the efficiency of the sago supply chain and move operations as close to the efficiency curve as possible, reducing the cost of production is necessary to set a competitive price for the product [41, 42, 43] and increase profit or return [15].

Figure 3: Sago supply chain efficiency curve (Adapted from Krajewski et al. [42])

Rapid improvement can be obtained by improving the design of the supply chain following better operation strategies to increase performance and by creating a new sago supply chain efficiency line. The goal of new dimensions of sago supply chain efficiency to reduce cost, increase profit, and balance supply and demand can be accomplished through farm production management, logistical systems, and knowledge and information (Figure 4). Finally, we would add an agronomy aspect due to the limited agronomical expertise required to maximize crop quality and maintain a balance between supply and demand [46]. However, we should note that every location will respond differently to each dimension due to local characteristics. In Riau, for example, farmers only focus on cultivation, hence the agronomy dimension will be emphasized to support farmers in adapting cultivation practices that can increase the quality and yield of the sago palm. Meanwhile, the logistic system is an important dimension in the eastern part of Indonesia, especially in Papua, where sago palms are found in scattered hamlets.

Figure 4: Dimensions of sago supply chain efficiency

Farm production management should be sought through continuous improvements in quality and post-harvest treatment, loss and wastage reduction, and elimination of the ijon system and credit tying. For post-harvest treatment, it is also suggested that the sago log should not be stored for more than 2–3 days at the very most, and should be stored preferably in water, because longer storage in dry conditions leads to deterioration in the quality of the starch [47] with a better extraction method afterward [48]. To minimize the loss of starch due to starch remaining trapped within the fiber, recovery of starch from the sago pith waste using a micro powder mill could be applied. A micro powder mill can increase sago starch production by 17% and it is applicable for sago farmers due to a short milling time [49]. Following ANJ Agri Papua, a private sago estate in Papua, their innovations in the extraction, log-rafting, debarking processes, and transitioning to biomass-fueled electricity generation drove cost reductions of almost 50% [50], which can be a good lead to increase efficiency in the production. Furthermore, increasing the profit of farmers can be achieved through loss and wastage reduction and at the same time without neglecting the environment. At present, many studies have attempted to utilize sago waste to produce useful materials. It can be used as a source for organic fertilizer, for feeding livestock, as a cheap substrate for production of the laccase enzyme, and for producing biodegradable foam [49, 50]. It is also reported the application of sago residue as an adsorbent for dangerous heavy metals [53]. The utilization of sago waste is expected not only to reduce the waste disposal into the environment but also to produce other beneficial materials as an added value to achieve sago supply chain efficiency.

Packaging plays an important function in the supply chain to make products safe, efficient, and cost-effective for shipping and distribution [52, 53, 54]. Therefore, it is important to consider prolonging the wet sago durability with better packaging to preserve its quality. Replacing tumang with plastic packaging and using water-packed or vacuum packing can preserve freshness by suppressing microbial growth in the product [57]. Meanwhile for dried sago, hygiene and safety standards should be applied to prevent low quality starch that produces financial losses for farmers. Increasing dried sago quality through standardization with better packaging and diversification of products with better promotional activities will surely attract consumers. In addition, marketing strategies should be developed to increase customers by identifying new market segments and geographical sales areas.

The ijon system and credit tying can be reduced by financial services such as village loans, promoting low-rates with no collateral credit. It is also suggested that a simple procedure of credit for farmers can be an alternative when the farmer needs money urgently. Involving a small-scale domestic trader/collector as a marketing actor is another reliable strategy. Although collectors are viewed negatively, they can be a driving force in agribusiness and the connector between traditional farmers and consumers. Therefore, instead of eliminating them, improving the efficiency of small-scale domestic trader is recommended with more transparent pricing and grading procedures [58], including the involvement of intermediary actor who understand the business climate, capital and financing in the cooperative. Since extended distribution channels result in higher marketing costs, direct marketing intervention and accessible open access market can also be used strategically to increase farmer’s profitability.

Another important dimension to support supply chain efficiency is logistic. Improvement of logistical performance has a positive impact on reducing production costs [59]. Currently, poor transport access is a major barrier for sago farmers in selling their products especially in the eastern part of Indonesia. Therefore, investing in road construction and facilities should be done by the government. It is also necessary to enhance intermediate activities such as storage, handling, and packaging to create logistical synergies between supply chain actors. Another strategy for the increase of farmers’ profit is the establishment of farmer group associations or cooperatives, which is an efficient mechanism to reduce transportation costs and enhance market access. The local government can learn from Riau and promote collective organizations for farmers in the eastern part of Indonesia to facilitate the bulk purchase and develop agribusiness partnerships, which increases sago farmers’ bargaining power. In addition, farmer organizations can form strategic relationships with other supply chain actors and increase adaptability in response to market demand [55, 56].

An increase in demand for sago starch affects the availability of sago palm, thus the dimension of agronomy in the supply chain should be examined to balance supply and demand for the sustainability of the sago industry. Since massive exploitation without replanting will lead to a loss of sago palm resources in the future, sago farmers should adopt a more cultivation-centered approach. Moreover, availability of high yield seedlings along with finding proper methods for seedling transportation are strategies that could lead to a significant increase in productivity and improve supply chain efficiency. Finally, quality seedlings that show satisfactory performance should be made available in sufficient quantities and at affordable prices to raise the productivity of smallholders.

To achieve supply chain efficiency, accessibility of knowledge and information for the farmer is really important. Farmers with better information will understand the regular market price of their product, which is advantageous for their business. It should also be noted that the adoption of improved technologies for small scale farmers must be practical and recognize local culture to avoid project failures. In addition, agricultural extension services provided by the government play a vital role in facilitating and providing appropriate training and information for farmers. It is noted that support from governments positively and significantly affects the business capacity of farmers [62]. Finally, special attention should be given to formulate policies for the development of the sago industry in rural areas, intensified upstream and downstream research activities, and better coordination involving authorities at the national, provincial, local levels, and research institutions.

All of the previous studies have concluded that sago industries in Indonesia hold an important position in driving rural development and remain viable considering their geographic location, raw material availability, and existing market demand. However, to date, there has been no significant achievement in the commercialization of sago palm by smallholders. This is due to the inefficiency of the supply chain from the upstream to the downstream, leading to a weak bargaining position for farmers. Our study indicates there is room to equip sago farmers with the knowledge and capacity needed to increase sago supply chain efficiency and provide products that meet the requirements of growth markets. In addition, further research should be done in each location to explore more specific solutions that align with the supply chain efficiency dimensions considering their local characteristics. Finally, better policies on sago palm development must be initiated in order to invest in more secure and sustainable rural livelihoods.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKEN Grant JP18KT0041. We thank anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback in improving this paper.