2013 年 230 巻 4 号 p. 255-263

2013 年 230 巻 4 号 p. 255-263

In Japan, the number of workers with depressive symptoms has increased recently, and long working hours are considered one of the main contributing factors. Currently, the number of workers engaging in discretionary work is small but is expected to increase, as a diverse method of employment is believed to contribute to workers’ well-being. However, the factors related to discretionary workers’ depressive symptoms are unclear. This study aimed to identify the factors associated with depressive symptoms in discretionary workers. The subjects were 240 male discretionary workers in a Japanese insurance company. A cross-sectional study was performed using a questionnaire that includes demographic characteristics, living and working conditions, work-related and non-work-related stressful events, and the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Depressive symptoms were assessed as more than 16 points on the CES-D. Multiple logistic regression models were employed to estimate odd ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of depressive symptoms in relation to possible factors. Thirty-six subjects (15.5%) showed depressive symptoms. The depressive symptoms were significantly related to age (p = 0.04), presence of child(ren) (p = 0.02), and length of employment (p = 0.01), but unrelated to working hours. Subjects who reported “financial matters” (OR = 4.50, 95% CI = 1.89-10.72) and “own event” such as divorce or illness (OR = 2.93, 95% CI = 1.13-7.61) were more likely to show depressive symptoms. In conclusion, mental health measures for discretionary workers should focus on addressing financial difficulties and consultations and assistance in personal health and family issues.

In recent years, a growing number of workers are experiencing job stress and depressive symptoms in the workplace (Tsutsumi 2009; Levinson et al. 2010; Cheng et al. 2012; Park et al. 2012). As if in response, there have been dramatic increases in workers’ accident compensation claims for mental disorders, with the number of workers’ accident compensation claims increasing from 952 cases in 2007 to 1272 cases in 2011 and the number of cases of certified worker’s compensation cases increasing from 268 in 2007 to 325 in 2012 (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012a). The diversity of work styles adopted by workers means that there is also variation in types of job stress. Recent studies indicate that there is a growing awareness of the importance of improving working conditions, including working hours as a psychosocial factor, and revising work environments as measures to prevent job stress (Egan et al. 2007).

In Japan, regulations controlling the total number of working hours are being promoted as one measure to prevent depression caused by job stress. The focus on control of working hours as a job stress prevention measure is a result of studies on the relationship between occurrence of job stress and illness showing a link between incidence of illness and work styles, which leads to regulations controlling long working hours and discretion over control of working hours (Fujino et al. 2006). Moreover, working long hours generally reduces the duration and quality of sleep and is linked to depressive symptoms (Yamasaki and Shimada 2009; Takahashi et al. 2011, 2012). The national labor administration in Japan thus proposed a number of recommended work styles that should be implemented by workplaces to control working hours as a component of health management (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2002). The findings reported indicate that regulations dealing with long working hours lead to improvement in depressive symptoms (Shima 2007).

Certain job categories and work styles do not allow for control of working hours. For example, sales personnel and journalists conduct their duties outside of the workplace, and calculating the number of hours worked is quite difficult. These categories of workers employ a more flexible work format. Japan has a Deemed Working Hours System for calculating the labor time of such workers. This is a discretionary labor system that is mostly limited to specialist job categories. The Deemed Working Hours System meets the occupational needs of individuals who work flexibly and independently. There has also been a need for managers to use this system, and the percentage of workplaces that have adopted the Deemed Working Hours System is slowly increasing (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012b). In the Deemed Working Hours System, overtime work can be calculated as a fixed proportion, regardless of the actual number of overtime hours, which enables stable calculation of wages and other aspects of income. In 2007, there were extensive debates on whether to adopt a “white collar” exemption bill premised on the Deemed Working Hours System as a discretionary labor system for white collar workers in Japan, but this bill was eventually shelved. One reason the “white collar” exemption bill was dropped is that it would extend applicability of the Deemed Working Hours System and could actually result in longer working hours, which would negatively affect health. Nevertheless, in fiscal 2012, the government relaxed requirements and procedures for adoption and application of the Discretionary Working System for Management-related Work that is limited to white collar workers involved in planning work (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012c), leading to substantial expansion of the discretionary labor system. Recent surveys show that 25.0% of companies are considering adopting the Discretionary Working System for Management-related Work (The Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training 2012).

However, very few studies have been conducted to examine the conditions of discretionary work and depressive symptoms of workers actually participating in the Deemed Working Hours System (Tarumi et al. 2002; Fujino and Matsuda 2007). In particular, there have been no studies investigating stressors for discretionary workers. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that working long hours is not always linked to depressive symptoms (Fujino et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2009) In the present study, sales personnel in a financial institution who participate in the Deemed Working Hours System and have a highly discretionary work style were surveyed, in an attempt to clarify (1) the prevalence of depressive symptoms among discretionary workers; (2) the relationship between depressive symptoms and working conditions, including aspects such as working hours; and (3) work-related and non-work-related stressful events related to depressive symptoms in discretionary workers.

In a cross-sectional study, questionnaire surveys were administered to employees at one of two offices of an insurance company with marketing bases throughout Japan. Cooperation was received from all sales workers at these two offices, and they were all selected to participate in the study. One office (Office “A”) was located in a city in the Kinki region with a population of about 1,500,000 people, and the other office (Office “B”) was located in a city in the Tohoku region with a population of about 330,000. The participants were restricted to male sales staff using the discretionary labor system from among employees at the insurance company, because the number of female sales staff using such a system was small. All participants were life insurance sales consultants. Basically, the employees had the responsibility to decide their methods of doing business at their sole discretion. Their working conditions involved mainly door-to-door sales, and they also used sales calls as supplements. Sales staff at the company, including sales managers, were deemed to perform highly discretionary work according to the following working conditions: (1) each employee makes his own decisions on subject and range of sales work; (2) each employee prepares work schedules and participates in the Deemed Working Hours System; and (3) employees receive basic remuneration plus rewards for individual business results.

ProcedureQuestionnaires were registered, but an anonymous envelope was included. Completed questionnaires were sealed in the envelope by each participant, so that the respondent could not be identified, and they were collected at each office by a health officer or public health nurse, who were the only ones to open the envelopes. The study was conducted from February to April, 2010.

MeasurementThe questionnaires included questions on baseline characteristics, working conditions, work-related and non-work-related stressful events, and depressive symptoms. The baseline characteristics were age and living situation (presence or absence of children and of other family living together). Working conditions covered the length of employment, position, and, to determine the presence or absence of long working hours, average working hours per day on work days, number of holidays in the last month, and average sleeping time per day. Work-related and non-work-related stressful events were assessed using 66 of the 75 items from the Occupational Mental Stress Evaluation Sheet and Non-Occupational Mental Stress Evaluation Sheet (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2009), excluding 9 items that were not relevant to the specific workplace examined in this study. Subjects were asked about the occurrence of each event over the last 6 months. These evaluation sheets are used as indices for certified worker’s compensation to determine whether the onset of mental illness in a worker was due to intense work-related stress. They list events that workers generally perceive as stressful, and they are shown with the intensity of the event (weak, moderate, strong). In the present study, each stressful event was not analyzed independently, but the focus was instead on the presence or absence of a type of stressful event that acts as a subscale. Work-related stressful events consisted of 6 types of events that were “experience of an accident or disaster,” “failure at work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc.,” “changes in the quantity and quality of work,” “change of status or roles etc.,” “interpersonal problems,” and “interpersonal changes.” Non-work-related stressful events consisted of 6 types of events that were “own event,” “event of family or relatives,” “financial matters,” “experience of incident or accident or disasters,” “changes in the living environment,” and “relationships with others” (refer to the Appendix for a list of events).

Statistical analysis and assessmentThe 20 items of the Japanese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radoloff 1977; Shima et al. 1985) were used to assess depressive symptoms. The CES-D is a screening test that asks subjects about their mood and feelings over the last week. Subjects select one of four responses (rarely or none of the time, some or a little of the time, occasionally or a moderate amount of the time, most or all of the time), and the total score is calculated to determine whether the subject has depressive symptoms. This test has been proven to be highly valid for assessing depression and is often used in workplaces (Wada et al. 2006; Ikeda et al. 2009; Kai et al. 2009; Takada et al. 2009; Yamasaki and Shimada 2009). The cutoff for the CES-D score was set to 16 points to enable comparisons with previous studies (Shima et al. 1985; Wada et al. 2006; Kai et al. 2009; Takada et al. 2009; Yamasaki and Shimada 2009).

As the objective variables, subjects scoring less than 16 points on the CES-D were placed in the low CES-D group (low level of depressive symptoms), and subjects scoring 16 points or more were placed in the high CES-D group (high level of depressive symptoms). Chi-square tests and t-tests were first performed to compare the percentages and means of each baseline characteristic, working conditions, work-related stressful events, and non-work-related stressful events between the low CES-D group and the high CES-D group. Then, the odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values were calculated using models adjusted for baseline characteristics and working conditions that differed between the low and high groups for each type of stressful event. Multiple logistic regression analysis models were then created using the stepwise method by adding baseline characteristics and working conditions that differed significantly to types of stressful events that differed between the low and high groups, and the OR with 95% CI and p-values were calculated.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS ver.16 statistical software, with the level of significance at 5% (two-tailed).

The study procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the Institute for Science of Labour (Public Interest Corporation Authorization).

A total of 234 responses (response rate: 97.5%) was received from 240 employees (office “A” 198 employees and office “B” 42 employees), and analysis was performed on 232 subjects (office “A” 190 subjects and office “B” 42 subjects), excluding 2 with missing values (valid response rate 96.7%).

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics and working conditions by CES-D score group. Thirty-six subjects (15.5%) were in the high CES-D group. Among the baseline characteristics, significant differences were seen in age and presence or absence of child(ren). For working conditions, a significant difference was seen in length of employment.

Table 2 shows the proportion of work-related and non-work-related stressful events divided by high and low CES-D scores. Work-related stressful events of “failure at work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc.” and “changes in the quantity and quality of work” were significantly more often experienced by subjects with strong depressive symptoms. Non-work-related stressful events of “own event,” “financial matters,” and “experience of incident or accident or disasters” were significantly more often experienced by subjects with strong depressive symptoms.

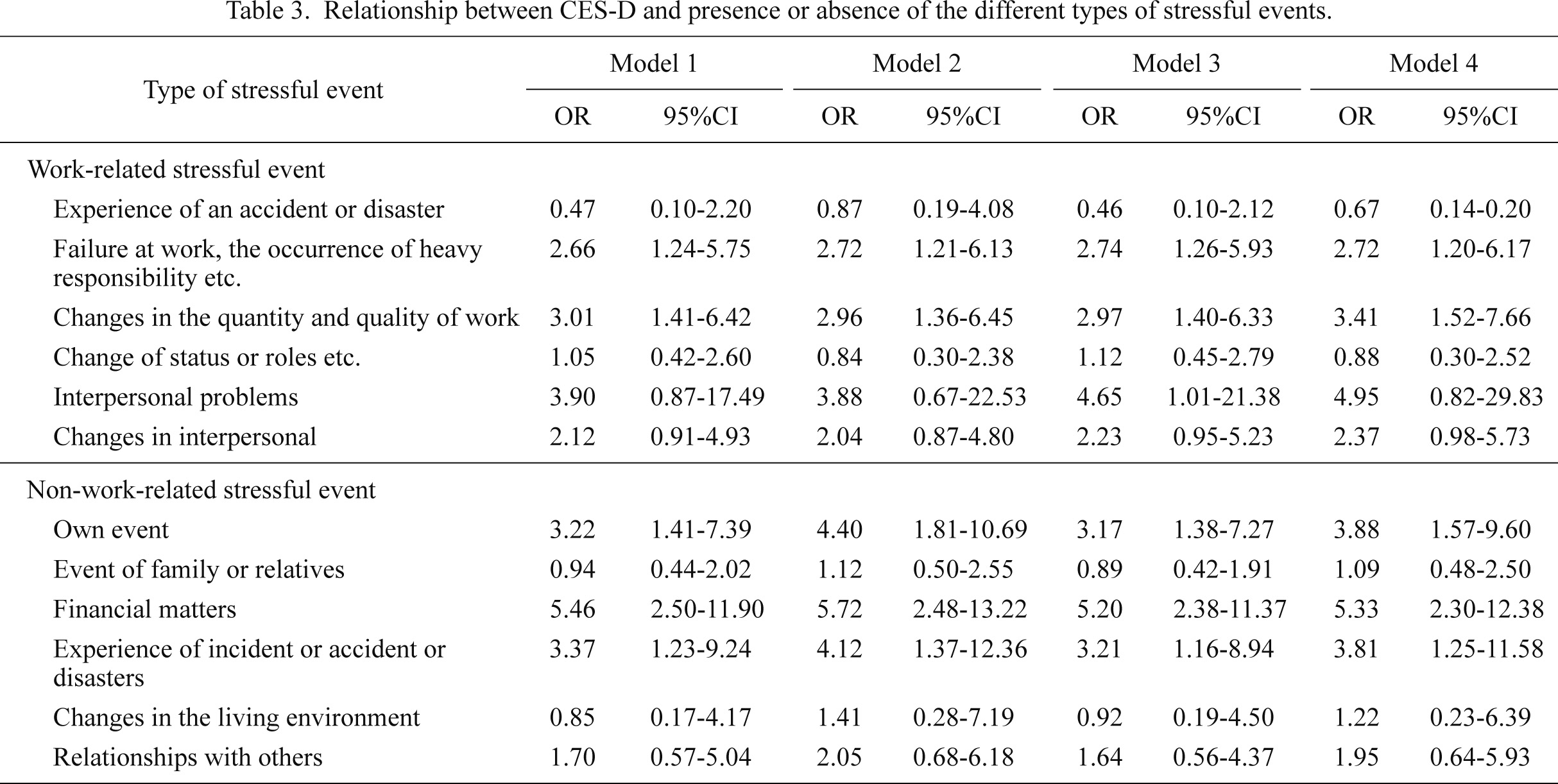

Table 3 shows the results of four models testing the relationship between each type of stressful event and CES-D, adjusted for age, presence or absence of child(ren), and length of employment, which were the factors among the baseline characteristics and working conditions that differed significantly between the groups. In every model, stressful events of “failure at work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc.,” “changes in the quantity and quality of work,” “own event,” and “financial matters” were experienced by a significantly higher proportion of subjects with strong depressive symptoms.

Table 4 shows the OR of factors related to a high CES-D score on multiple logistic regression analysis. The stepwise method was performed using the baseline characteristics and working conditions found to be significantly different in Table 1 (age, presence or absence of child(ren), length of employment) and the types of stressful events found to be significantly different in Table 2 (“failure at work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc.,” “changes in the quantity and quality of work,” “own event,” “financial matters,” and “experience of incident or accident or disasters”). Non-work-related stressful events of “financial matters” (OR = 4.50, CI: 1.89-10.72) and “own event” (OR = 2.93, CI: 1.13-7.61) were experienced by a significantly higher proportion of subjects with strong depressive symptoms. There was no significant association between strong depressive symptoms and the work-related stressful events of “failure at work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc.” or “changes in the quantity and quality of work.” The most common stressful event in the category of “financial matters” was “income decrease” (n = 75), and in the category of “own event” it was “own illness or injury” (n = 20).

Moreover, the ORs of each item under the type dealing with “financial matters” and “own event” related to a high CES-D score were as follows. For “financial matters,” “Substantial loss of assets or sudden major expense” (OR = 6.33, CI: 1.92-20.93), “Income decrease” (OR = 3.68, CI: 1.77-7.66), “Overdue debt payment or trouble paying debt” (OR = 7.64, CI: 2.19-26.60), and “Received a mortgage or consumer loan” (OR = 9.22, CI: 2.74-30.99) were all significantly associated with a high CES-D score. For “own event,” “Divorce or separation” (OR = 11.47, CI: 1.01-130.02) was significantly associated with a high CES-D score, while “Own serious illness or injury or miscarriage” (OR = 0.84, CI: 0.80-0.89), “Own illness or injury” (OR = 0.58, CI: 0.13-2.62), “Marital problems, quarreling” (OR = 13.93, CI: 4.74-40.97), and “Mandatory retirement” (OR = 0.84, CI: 0.79-0.89) were not associated. These data are not shown in the table.

Demographic characteristics and working conditions by CES-D score of 16 or higher or less than 16.

s.d., standard deviation.

aIndependent Student’s t-test. bChi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

Ratio of work-related and non-work-related stressful events by high and low CES-D score.

Chi-square test. aLow group: CES-D < 16 point, bHigh group: CES-D ≥ 16 point

Relationship between CES-D and presence or absence of the different types of stressful events.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Model 1 : Adjusted for age, Model 2 : Adjusted for child, Model 3 : Adjusted for length of employment,

Model 4 : Adjusted for child and length of employment.

Odds ratio of factors related to CES-D score on multiple logistic regression analysis.

Variables: presence or absence of child(ren), length of employment, stressful event, failure of work, the occurrence of heavy responsibility etc., changes in the quantity and quality of work, own event, financial matters, experience of incident or accident or disasters.

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The variables were excluded using a stepwise procedure.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study to clarify depressive symptoms, living situations, and working conditions in discretionary workers, as well as the relationship between depressive symptoms and work-related and non-work-related stressful events. The primary objective of this study was to investigate the prevalence of depressive symptoms in discretionary workers, and the results showed the prevalence to be 15.5%. This percentage is quite low compared to general workers, as shown by previous studies. For example, the prevalence of depressive symptoms has been reported to be 35.8% among workers in the manufacturing industry (Yamasaki and Shimada 2009) and 22.7% (Wada et al. 2006) or 27.5% (Takada et al. 2009) among male workers according to studies that widely investigated depressive symptoms in employed workers. Considering that most subjects in the present study were likely to have accepted the condition of working in a highly discretionary manner when joining the company, the prevalence of discretionary workers showing depressive symptoms would not necessarily be high.

The second objective of this study was to examine the relationship between high depressive symptoms in discretionary workers and their working conditions, which are highly constraining, with long working hours and few holidays. No such association was seen. Other studies have also confirmed a lack of a significant association between long working hours and depressive symptoms in non-discretionary workers, for whom work time can be controlled (Fujino et al. 2006; Sato et al. 2009). The lack of an association with depressive symptoms in those performing highly discretionary work may be due to their strong acceptance of working long working hours as being their own decision. This point may be important when considering measures to prevent job strain in discretionary workers. Regarding control of working hours, regulations controlling the total number of working hours may be less of a priority for those performing highly autonomous work.

There was no significant association between depressive symptoms and length of sleeping time, which is one factor related to working conditions. It has been reported that work that allows highly independent control of working hours is associated with better sleep and health (Takahashi et al. 2012). This agrees with the result of the present study that depression in discretionary workers was not related to working hours. Studies on workers considered to be non-discretionary workers (Kai et al. 2009) or examining a broad range of occupations (Takada et al. 2009) indicated that there is a link between sleep and depressive symptoms, especially in male workers. This does not match the finding of the present study. A relevant point may be that discretionary workers may be able to choose to sleep when they feel the need.

The third objective of this study was to examine the relationship between depressive symptoms and work-related and non-work-related stressful events. No association was observed between work-related stressful events and depressive symptoms. The presence of depressive symptoms in discretionary workers was strongly associated with “financial matters” as a non-work-related stressful event, followed by personal injury or accident or “own event,” such as family matters. A distinguishing feature of this result is that depressive symptoms were strongly associated with non-work-related stressful events rather than work-related stressful events. The accuracy of this model was quite high, at 84.7%. In the present study, questionnaire responses were registered to enable complementary investigation of the relationship between remuneration and depressive symptoms. However, no association was seen between CES-D and remuneration for the relevant fiscal year (calculated based on sales performance rank). Specifically, there was no link between annual remuneration amount and depressive symptoms. However, all items involving stressful events related to “financial matters,” including “income decrease” or “debt,” were associated with strong depressive symptoms. In view of this finding, “financial matters” for discretionary workers may refer to problems regarding loans and other household income and expenditure or income instability. Discretionary workers, who were the subjects of this study, are employed workers who are eligible for social insurance, but who also perform highly discretionary work, similar to self-employed workers. Previous studies indicated that lack of security is a stress factor for self-employed workers (Oren 2011). While discretionary workers do have security, household income may be more difficult to manage for them than for non-discretionary workers. This is congruent with previous studies that have confirmed a link between debt and depression (Bridges and Disney 2010), and a statistic reported by the National Police Agency (2012) identifying “financial problems” as the number two most common reason for suicide. In discretionary workers, attention must be focused on “financial matters.” It is thus necessary to improve the system for providing consultations and other types of assistance concerning temporary changes in remuneration and household income in addition to work style.

Studies have found that self-employed workers are more prone to physical ailments and have more work-family conflicts than employees (Oren 2011), which may concur with the present finding that “own event” is a stressful event linked to depressive symptoms. In highly discretionary work, this may be similar to mental and physical health problems in self-employed work, which is a similar work style. While lack of discretionary power has been cited as a stressor in employed workers, the subjects in the present study have more discretionary power than regular employees. In contrast to self-employed workers who lack security, they also have social security. From these two points, discretionary work can be considered a work style that offers both flexibility and security to workers.

The presence of depressive symptoms was not associated with whether the subject lived together with a family member, but it was associated with the presence or absence of children, which is a unique finding. While previous studies have found a link between the presence or absence of a co-resident and depressive symptoms (Weissman 1987; Yamasaki and Shimada 2009), the present study suggests it may be worthwhile to focus on the actual type of co-resident for the case of discretionary workers.

Asakura (2001) suggests that mental stress will be relieved in workers if the discretionary labor system is implemented with the following six points: (1) setting appropriate work volume, quality, and deadlines; (2) setting clear work targets; (3) making work highly discretionary, for example by allowing employees to choose their progress management and execution methods; (4) increasing transparency of performance-based evaluation and evaluation criteria and establishing fair evaluation practices; (5) developing self-management skills in workers; and (6) as a condition, providing a workplace/company culture that values individual autonomy and a foundation where workers are accustomed to being personally evaluated and are given the opportunity to make up for mistakes. In addition to these conditions, the results of the present study suggest that stress in discretionary workers can be relieved by focusing on private life, specifically improving support and consultations for “own events” such as household financial matters, family conflict, and personal illness.

This study had some strengths. One is that the data extracted are likely to have little bias, as they came from employees of an insurance company in a large city and a mid-sized city, and the response rate was quite high. In addition, the stepwise method with a multiple logistic regression model used to identify the final significant factors was considered to have high validity.

The present study also had a number of specific limitations. One is that it was a cross-sectional study and, thus, does not show causality. However, it investigated stressful events over the last 6 months and recent depressive symptoms, and, in principle, depressive symptoms do not trigger stressful events. Thus, causality can be predicted despite it being a cross-sectional study. The second limitation concerns use of the CES-D to measure depressive symptoms. The CES-D measures acute depressive symptoms and may not reflect medium- to long-term depressive symptoms (Yamasaki 2008). However, it is a widely used scale and thus enables comparison with other studies and elucidates the relative prevalence of depressive symptoms in discretionary workers. As a third limitation, the study did not involve non-discretionary workers as a control group for comparison purposes. As a fourth limitation, the measurement of working hours may be inaccurate, since quantification of working hours is difficult for this particular style of work, and the responses on working hours were self-reported. Finally, it may be difficult to generalize the results to all discretionary workers, as the study only looked at one company where employees generally accepted the condition of discretionary work when joining the company and where they only conducted the specific work of insurance sales.

The diversity of employment formats has been growing in Japan in recent years, and increased flexibility of working styles in the future is unavoidable (Asao 2010). Discretionary labor and mental health must be studied more widely, with particular priority placed on studies examining the Deemed Working Hours System that is already in place. Currently, about 12% of companies employ the Deemed Working Hours System in Japan, and this percentage is slowly increasing (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2012c). The present study suggests that the health management strategy used in the Deemed Working Hours System that only controls time in the workplace is insufficient.

In conclusion, focusing on financial problems and consultations and assistance in personal health and family issues may be higher priority issues for mental health measures aimed at discretionary workers than control of working hours.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Work-related stressful event

Non-work-related stressful event