2014 Volume 232 Issue 3 Pages 155-162

2014 Volume 232 Issue 3 Pages 155-162

The loss of a baby is a traumatic event, irrespective of the duration of pregnancy. In the present study, we attempted to recognize the opinions of women after miscarriage that needed assistance and support from the medical staff during hospitalization. The study was conducted during the period from January to June 2012 and included 303 women who miscarried and used medical care in the Lublin Region (Poland). The method of a diagnostic survey was applied using a questionnaire technique. The majority of the respondents reported that information obtained from physicians after the diagnosis of miscarriage were rather understandable (44.22%) and sufficient (41.91%). According to more than a half of respondents, after miscarriage, midwives demonstrated adequate skills (57.43%) and provided necessary informative support (52.81%). The study showed that during hospital stay the women who had experienced miscarriage evaluated in relatively high terms the physicians and midwives providing them with care. The evaluations of the attitudes of doctors and midwives increased with the women’s growing needs during hospitalization. The results of the study allow the presumption that the medical staff providing care of women after miscarriage possess a relatively high level of knowledge and skills in the area of diagnostics and treatment of pregnancy terminated with miscarriage. However, it should be remembered that the constant training of doctors and midwives in the provision of emotional and psychological support is necessary.

Spontaneous abortion is a premature loss of pregnancy, in which an alive/dead embryo or foetus born before the 22nd week of gestation. Approximately 10-15% of pregnancies are terminated with miscarriage, and 80% of the cases of pregnancy loss take place in the first trimester. Statistical data show that every 6th pregnancy is miscarried within the first 14 weeks of gestation. The most frequent cause of miscarriage is the pathology of the ovum; sometimes, factors on the mother’s side play an important role, while in the remaining cases the causes remain unknown (Nikcevic et al. 2007; Andersson et al. 2012; Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero 2012).

Miscarriage is a difficult experience, not only for a woman, but also for her partner. Both equally strongly experience the death of their baby, each of them in the own way. A woman usually blames the existing situation and considers that her behaviour has contributed to the miscarriage, her conviction being additionally confirmed by the fact that approximately 50% of miscarriages are of unknown etiology (Lok and Neugebauer 2007; Nikcevic et al. 2007; Adolfsson 2010; Lang and Nuevo-Chiquero 2012).

Emotions that usually accompany the first moments after miscarriage are usually shock, helplessness and lack of acceptance of the loss of a baby, and then anger occurs, followed by negation, feelings of guilt and anxiety. In about 90% of women after miscarriage, there occurs reactive depression, usually lasting for about 2 months, of which 40% of women are diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Łuczak-Wawrzyniak et al. 2010).

After miscarriage, every woman experiences a ‘baby loss syndrome’, which may manifest itself in many ways, and in each case the woman needs support and assistance from professionals: midwife, physician, or sometimes even a psychologist (Łuczak-Wawrzyniak et al. 2010; Murphy and Philpin 2010; Andersson et al. 2012). In the present study, we attempted to recognize the opinions of women after miscarriage who, having experienced such a difficult and traumatic event, needed assistance and support from the medical staff (midwives, doctors) providing them with care during hospitalization.

The basic study was preceded by pilot studies carried out from January to June 2012 and covered 350 women, from several days to 2 month after the loss of pregnancy. They were the patients of gynaecological wards at the regional hospitals in Zamosc and Lublin, and provincial hospitals in Chelm, Tomaszow Lubelski, Hrubieszow, Poniatowa, as well as patients covered with care by outpatient departments for women and by family midwives in the Lublin region. The study was conducted in accordance with the assumptions of the Declaration of Helsinki, and consent was obtained from the Ethical Committee of the Polish Midwives’ Association (IV/EC/2011/PMA). Women participating in the study were informed concerning voluntary and anonymous participation in the study, and that the results obtained were for scientific purposes only. As many as 303 completely questionnaires were qualified for the final analysis.

The study was carried out by the method of a diagnostic survey with the use of a questionnaire form designed by the author, which covered items pertaining to the respondents’ characteristics (age, marital status, place of residence, maternal experience, material standard, housing conditions), based on analysis of the relevant literature, developed based on a 5-point Likert scale.

Database and statistical data were analyzed using computer software STATISTICA 9.0 (StatSoft, Poland). Differences between groups were analyzed using Man-Whitney U test, whereas for more than two groups, Kruscal-Wallis test was applied. Relationships between variables were investigated using Spearman’s rank correlation. The p values p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 1 presents socio-demographic data concerning the 303 women participating in the study, with the majority of respondents aged 26-30 (31.68%), married (76.24%), urban inhabitants (54.13%), with secondary-school education (37.95%), possessing one child (35.97%), and those who possessed two or more children (35.97%), who evaluated their material standard (46.86%) and housing conditions (46.20%) as good.

The majority of respondents declared that the information obtained from physicians after miscarriage were rather understandable (44.22%), and sufficient (41.91%), and similarly evaluated information obtained from a physician while performing examinations and procedures (38.94%). More than one fourth of the women after miscarriage (28.71%) admitted that they did not receive sufficient psychological support from physicians, and nearly one fifth of respondents mentioned that they definitely did not obtain such support (22.44%) (Table 2). Further statistical analysis concerned the evaluation of physicians in the situation of miscarriage, the respondents providing replies according to the scale from 1-5 scores, where: 5 scores - definitely Yes, and 1 score - definitely No. Maximum evaluation was 55 (a very high evaluation), while the mean evaluation of physicians providing care was 33.07 ± 13.49 (11-55 scores).

The majority of women in the study reported that after miscarriage midwives showed adequate skills (57.43%), provided them with necessary informative support (52.81%), and positively evaluated midwives’ knowledge (45.21%) and their conduct, which exerted an effect on their emotions during this period (45.21%). In turn, more than two-fifths of respondents (41.58%) were not able to express whether midwives’ conduct had a positive effect on their partner’s emotions, and nearly one-third (32.34%) had no opinion whether the partner/father of the baby obtained adequate psychological support from midwives, whereas 45.21% of respondents admitted that midwives who provided care rather did not avoid contacts with them, and according to 37.95% of respondents, the midwives rather did not keep their distance (Table 3).

During further statistical analysis, midwives’ behaviour was analyzed in the situation of pregnancy loss, where the maximum evaluation was 70 (a very high evaluation). The mean evaluation of midwives who provided care for women after miscarriage was 48.61 ± 9.43 (21-70 scores).

Table 4 presents the evaluation of midwives and physicians in opinions of women after miscarriage with consideration of their psychological status. Statistical analysis showed that respondents who could freely express their emotions during hospitalization evaluated physicians and midwives providing them with care in significantly higher terms (p < 0.0001) than respondents who had no such an opportunity, or did not remember that fact. Respondents, who evaluated their psychological status after miscarriage as severe, expressed better evaluations of assistance and support provided by physicians (p < 0.001) and midwives (p < 0.01), compared to those who evaluated their status as moderate or light (p < 0.001).

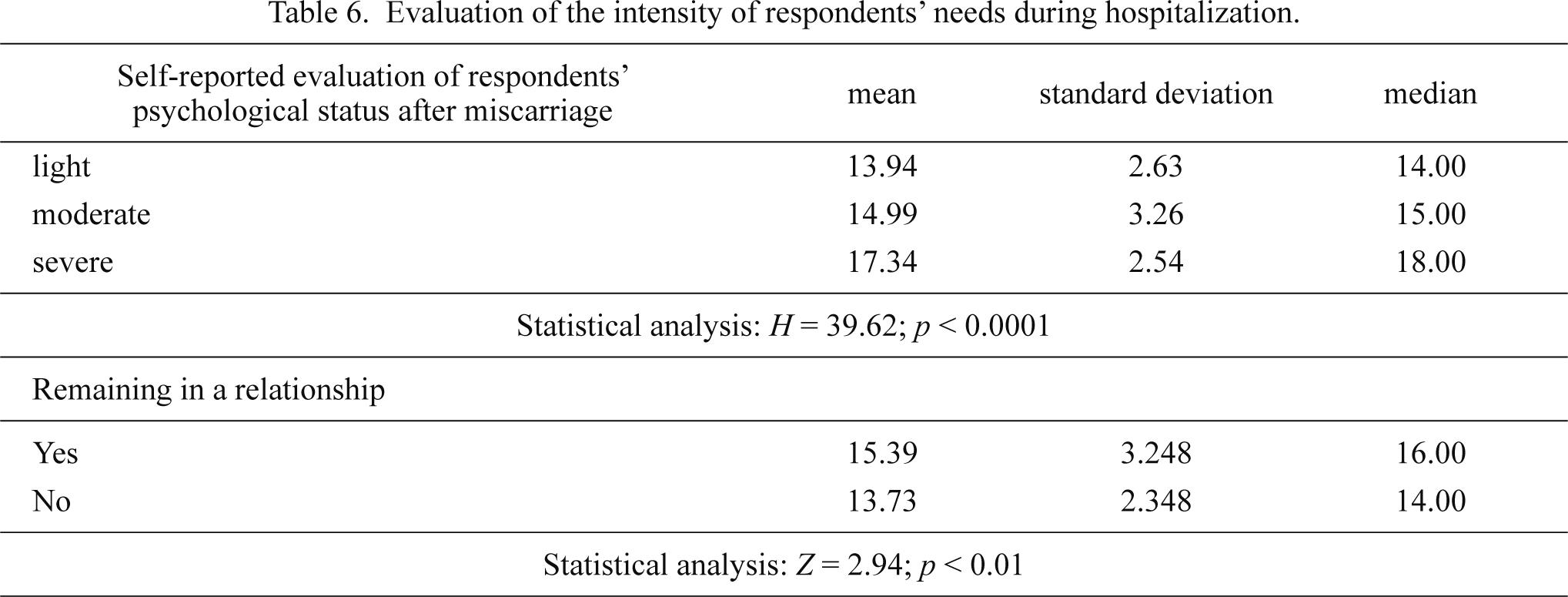

More than a half of the respondents needed peace and quiet during hospitalization (58.09%), understanding (50.50%), nearly one-third expected seclusion (31.68%) and conversation (31.68%) (Table 5). Based on the statistical analysis, the mean evaluation of the respondents’ needs during hospitalization was 15.22 ± 3.21 (5-20 scores).

Respondents who evaluated their psychological status after miscarriage as severe had more intensified needs during hospitalization than the respondents who evaluated their psychological status as light or moderate (p < 0.0001). Respondents who at the time of pregnancy loss were married had significantly more intensified needs, compared to those who were single (p < 0.01) (Table 6).

The results of study showed a significant correlation between the level of intensity of needs during hospitalization and evaluation of physicians (R = 0.23; p = 0.00005, Fig. 1) and midwives (R = 0.23; p = 0.02, Fig. 2). The higher the intensity of patients’ needs, the more positive the evaluations of physicians and midwives providing them with care.

Statistical analysis showed that the respondents who received complete and sufficient instructions from the medical staff concerning follow-up assistance after the loss of a baby evaluated both physicians and midwives in more positive terms, compared to those who had insufficient information or did not obtain any information at all (p < 0.0001) (Table 7).

Respondents’ socio-demographic data.

Evaluation of attitudes of physicians providing respondents with care.

Evaluation of attitudes of midwives providing care for women after miscarriage.

Evaluation of physicians and midwives in opinions of women after miscarriage, with consideration of their psychological status.

Evaluation of respondents’ needs during hospitalization.

Evaluation of the intensity of respondents’ needs during hospitalization.

Correlation between intensity of respondents’ needs and evaluations of physicians.

N = 303.

Correlation between intensity of respondents’ needs and evaluations of midwives.

N = 303.

Evaluation of physicians and midwives with consideration of receipt of information from staff concerning the instructions about follow-up assistance after loss of a baby.

In the majority of women, pregnancy evokes positive emotions; therefore, the loss of a baby, irrespective of the duration of gestation period, is a traumatic experience, and sometimes leads to serious psychological consequences (Adolfsson 2010).

Smith et al. (2006) in their studies emphasized that despite the fact that women after miscarriage rarely expressed negative opinions concerning care provided by medical staff, these opinions are of great importance. A small number of respondents perceived medical care as cool and incomplete, they also felt lonely. Although the loss of a baby usually evokes in a woman helplessness, sadness and grief (Nikcevic et al. 1998; Brier 2008). Kelley and Trinidad (2012) presented in their studies the experience of still birth from the perspective of parents and physicians. For women and parents, still birth is a severe and sad experience, and the assistance offered by the medical staff did not always bring the desired effect. Physicians, although they noticed patients’ grief, did not perceive its duration and depth. For physicians, still birth is an unexpected clinical tragedy which is very hard for patients, and also for themselves, because they cannot provide an answer concerning the cause. Studies by Wong et al. (2003) showed diversified opinions concerning medical staff by women who had experienced a miscarriage. On the one hand, doctors and midwives underestimated miscarriage, and perceived it as a situation that happens all the time, or did not show empathy; but on the other hand, showed deep understanding and great help. The results of the present study show that information obtained from physicians after the diagnosis of miscarriage were rather understandable (44.22%) and sufficient (41.91%); however, 28.71% of women after miscarriage considered that they rather did not receive sufficient psychological support from physicians. According to the respondents’ opinions, the mean evaluation of physicians was 33.07 ± 13.49 (11-55 scores).

Studies by Murphy (1998) concerning the perception of miscarriage from the male perspective, indicated that all respondents felt very lonely while coping with this experience. The majority of men reported that they obtained support mainly from their significant others (friends, family, partner), rather than from the medical staff.

The presented study shows that 41.58% of women in the study were not able to evaluate whether midwives’ conduct exerted a positive effect on their partner, and 32.34% of respondents could not say whether their partner/father of a baby obtained adequate psychological support from midwives.

In turn, the study by Krajewska-Kułak et al. (2010), concerning the acceptance of the state of health by patients in pregnancy pathology and maternity wards, revealed that respondents with threatened miscarriage (15.0 ± 1.8), after spontaneous abortion (17.3 ± 1.5), and with threatened premature birth (18.2 ± 1.7), did not accept their health situation. The present study confirmed a significant relationship between the level of intensity of needs during hospitalization and the evaluation of physicians (R = 0.23; p = 0.00005) and midwives (R = 0.23; p = 0.02); therefore, the evaluations of attitudes of medical staff increased together with the intensity of needs.

After the loss of a baby, women expect emotional support; however, they are not always able to specify their needs. Midwives usually recognize these needs and provide the women with support in especially difficult situations (Thorstensen 2000; Adolfsson et al. 2006). According to the assumptions of Swanson’s Caring Theory, a midwife is a sympathetic person who treats a woman with dignity, respect and delicacy, possesses the indispensable communication skills to help a woman after miscarriage in understanding the process of grieving, while at the same time recognizing and satisfying her needs. After the traumatic experience, miscarriage, a midwife tries to improve the patient’s general wellbeing, and her physical presence when needed (Adolfsson 2011). The majority of women in the study reported that after miscarriage the midwives showed adequate skills (57.43%) and provided adequate informative support (52.81%). In turn, 45.21% of respondents mentioned that midwives who provided them with care rather did not avoid contact, and in the opinions of 37.95% of respondents, a midwife did not keep her distance. Statistical analysis showed that the mean evaluation of midwives’ was relatively high, 48.61 ± 9.43 (21-70 scores).

Communication skills are an elementary component of nursing-obstetric care. A competent midwife, apart from the skills of performing medical procedures or nursing activities, covers the patients with overall care biased towards support, a ‘good word’ in order to bring relief in suffering (Włoszczak-Szubzda and Jarosz 2012, 2013). The review of literature and analysis of the results of own studies allow the presumption that medical staff, including physicians and nurses, provide professional care of a patient during miscarriage and in the subsequent phases of grieving after the loss of a baby (Iles 1989; Krause and Graves 1999; Hildingsson et al. 2002; Brier 2008).

In conclusion, the present study showed that women after miscarriage, during their hospital stay expressed relatively high evaluations of physicians and midwives providing them with care. The evaluations of physicians and midwives increased with the needs of women during hospitalization. Women who had an opportunity to freely express their opinions, during hospitalization perceived their psychological state after miscarriage as severe, obtained complete information, and evaluated medical staff in more positive terms. The authors of the present study would like to emphasize that in order to provide the best quality care possible, and satisfy the expectations of women after miscarriage, physicians and midwives should constantly improve their qualifications in the area of provision of emotional and psychological support for women, who had experienced such a difficult event.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.