2015 Volume 235 Issue 2 Pages 97-102

2015 Volume 235 Issue 2 Pages 97-102

Japan ranks low in the global gender gap index. Academic promotion is difficult for women doctors, and the leaky pipeline of women doctors is evident in academic medicine. The Japan Surgical Society (JSS) has 2,874 (7.2% of total membership) female members as of April 2014. The total number of councilors in JSS has increased, but there is still only one female member on the Council. The fact that there are so few women in decision-making positions makes it challenging to fight for equality. The Japanese Association of Medical Science (JAMS) is an association with exclusive institutional membership comprising the major medical societies in Japan, and currently has a membership of 122 specialist medical societies. It is essential to have at least one female committee member in each committee of the JAMS, which would provide opportunities to establish career paths for women doctors, to make rules that suit the lifestyle of women doctors, and to improve work-life balance.

Japan ranks the 104th out of 142 counties in the global gender gap index (World Economic Forum 2014). It is still not easy for women to hold jobs with responsibility in Japan.

The Prime Minister, Mr. Shinzo Abe, wrote that the universal medical care system of Japan is excellent (Abe 2013). However, there is no mention that the working environment of surgeons who support the system is far from desirable (Hanazaki et al. 2013). Mr. Abe enthusiastically comments on the success of women in business, while it seems that women physicians in academic medicine and medical societies are rarely mentioned.

In 1885, Dr. Ogino Ginko was the first woman to receive a medical license and to practice Western medicine in Japan. Since then, women doctors in Japan have increased gradually and now occupy 19.7% of all doctors (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare 2013). Women still work in a male-oriented working environment, although it is imperative to build a working environment with flexible and diversified working styles for women doctors. To achieve such environment, it is necessary to review the policies of medical societies by committee members and directors with broad outlook and updated ideas.

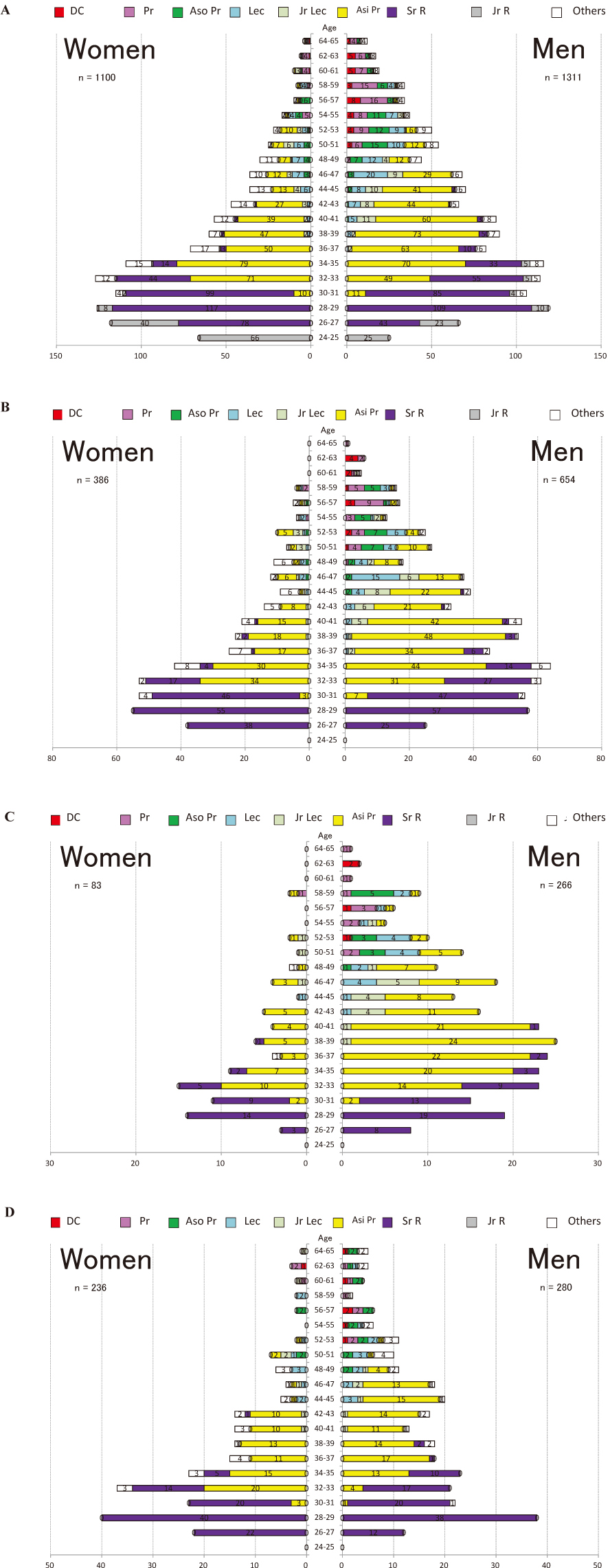

Women physicians’ leaky pipeline is markedly evident in academic medicine (Okoshi et al. 2014), and it is difficult for women to be promoted to higher positions (Fig. 1A) (Tomizawa et al. 2014a). In Tokyo Women’s Medical University (TWMU), a decrease in women doctors is obvious among faculty members in departments utilizing operating rooms, such as surgery, anesthesiology, otorhinology, otolaryngology, dermatology, ophthalmology, urology, obstetrics and gynecology (Fig. 1B) and in surgical specialties affiliated with the Japan Surgical Society (JSS) (all surgical specialties except brain surgery, orthopedic surgery and plastic surgery) (Fig. 1C). A main reason is that women doctors often leave job when they become pregnant. Colleagues often do not welcome women doctors who are pregnant since the workload increases when they are on maternity or childcare leave and there is no replacement due to the fixed number of staff members that can be employed in each department. There is another issue. If there is no 24-hour childcare facility or sick child facility available at the workplace and no cooperation from the husband, child rearing is stressful for women doctors. Childcare facilities and facilities for sick children as well as understanding and consideration about childcare in the workplace should be offered to reduce stress (Troppmann et al. 2009; Tomizawa et al. 2014b).

In Japan, the declining birthrate and growing elderly population are prominent issues. The ideal years for childbearing coincide with the time when women surgeons are in training. As a result, they delay childbirth until later years and often require treatment for infertility. A change in the regulations for specialty accreditation would facilitate maternity and child rearing leave for women surgeons and allow them to resume their career afterwards, in accordance with the current global trend.

The number of women physicians in internal medicine departments at TWMU decreases sharply around 42-43 years of age (Fig. 1D). There are other important issues in Japan other than infertility, such as “hurdle of first grade of elementary school”, and “entrance examination to prestigious high school or university”. When women physicians want to have a family, they have to leave work because of family responsibility, since their priority is the family’s happiness.

The Japanese Association of Medical Science (JAMS) is an association with exclusive institutional membership comprising the major medical societies in Japan, and currently has a membership of 122 specialist medical societies. In the JAMS, the ratio of women in positions of decision-making is either still low or zero. In committees in which woman’s viewpoints and opinions are necessary to change and improve woman’s carrier path, women councilors must be included since the absence of women on the committee will be a disadvantage for career formation of women.

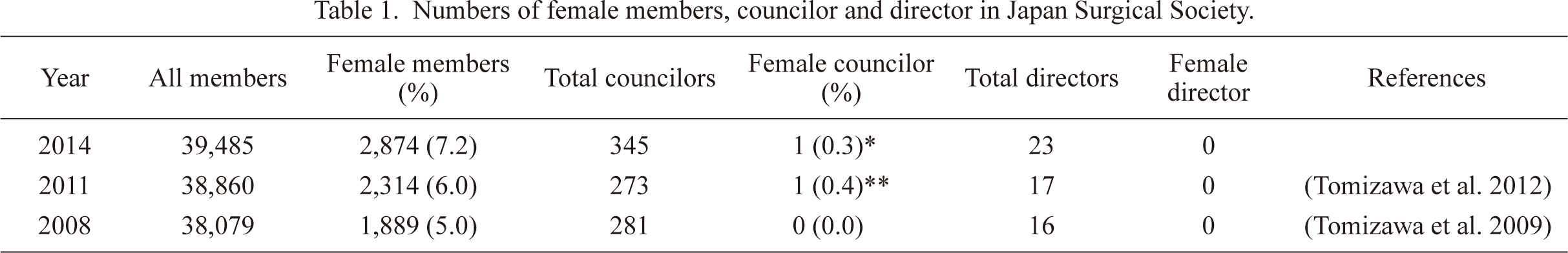

According to the 2012 report of JAMS, JSS had the largest female membership of 2,314 in surgical societies include all societies with “surgery” in their names, followed in the second place by the Japanese Orthopedic Association with 1,113 female members, and in the third place by Japan Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery with 1,095 female members. JSS has 2,874 (7.2% of total membership) female members as of April 2014 (Table 1). There was one nominated female councilor in 2011. Then the election system in JSS changed seeking for “fairness”, since they said nominated councilors were not fairly selected. In 2012, one female member ran for election and lost, and there was no female councilor during 2012-2013. And, one female councilor was selected without voting action in 2014. On the other hand, there was an increase of 72 male councilors during the last two years, with a total of 345. However, there is still only one female councilor in JSS, and the percentage of a female councilor among all councilors has decreased to 0.3%.

According to the 2012 report (Tomizawa et al. 2012), the number of female councilors was 17 in Japanese Society of Pediatric Surgeons, 4 in Japan Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 3 in Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery, and 2 in Japan Neurosurgical Society. Between 2011 and 2014, the number of female councilors increased from 2 to 3 in Japanese Society for Cardiovascular Surgery, and from 0 to 5 in Japanese Association for Chest Surgery. The Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Surgery changed the election system from a universal performance score system to score system with consideration for female members, and will have more than 5 female councilors in January 2015. To increase diversity by increasing the number of female councilors, the conventional rules mainly determined by male members in the past should be reviewed and updated.

The fact that there are so few women in decision-making positions in JAMS makes it challenging for women to fight for equality. There was an increase of 6 directors, with a total of 23 in JSS. It is also noteworthy that there has not been a female director for the last 114 years. In the past ten years, the procedure of director election (Japan Surgical Society 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2010, 2012) and director by-election (Japan Surgical Society 2009, 2011) in JSS involved indication of approval by applause without voting.

From two previous reports (Tomizawa et al. 2009, 2012), the proportion of female members in JSS is estimated to reach 10% in six years. This makes it necessary to take measures to improve surgeons’ work-life balance so that women are not further prohibited from positions of authority and career advancement.

It is difficult for non-councilor female physicians to assume committee leadership positions in JAMS (Tomizawa 2013). In May 2014, after many years, finally several female committee members have been included in JSS. It is very rare for a woman to be appointed as editor of an English journal in all the surgery member societies of JAMS (Tomizawa 2014). In 2014, the second woman, Dr. Kaori Okugawa was appointed as an editor of “Surgery Today”, the official journal of JSS, showing a sign of improvement.

The ideal situation is that women surgeons achieve leading positions on a par with their men counterpart, and are allowed to be professionally active while having a balanced family life, thus preventing leakage from the pipeline. It will take more than one female councilor to act on behalf of all women surgeons.

At least one female member should be included in each committee in JAMS (Mizoguchi 2004; Hiyama et al. 2014), but many JAMS member societies are behind in gender equality for choosing councilors and committee members. Professor Tadashi Iwanaka, Chief Director of Japanese Society of Pediatric Surgeons (2009-2010), included at least one female member in each committee during his tenure, the first of such endeavor in surgical societies. Then the next executive director (2011-2012) created a Work Life Balance Committee and appointed the first woman surgeon as chairperson in one committee. After that, the succeeding executive director (2013-present) appointed another woman surgeon as chairperson, with a total of two now.

In the 2012 report, the Japan Medical Association (JMA) initiated “Movement of 10% Quota for Women” and stipulated that each committee should include at least one female member (Japan Medical Association 2014). JMA indicated target numbers for gender equality. On the other hand, few member societies of JAMS have targets. Without setting target numbers, it is impossible to achieve gender equality.

In JSS, the committee for councilor election in each electoral district controls the number of candidates. Therefore, both men and women members cannot freely run for election. The activity of councilor election is perfunctory and most of the members were not familiar with the system. Very few members with the right to vote have ever seen the voting slip. Councilors should be appointed based on performance, and evaluated for eligibility based on objective criteria.

There are still few female councilors in JAMS, and establishment of a gender quota system cannot be realized by vote because female members are still the minority. However, a gender quota system is essential to address the issue of gender disparity. Another issue exists at academic facilities. Due to political reasons usually involving the department head, voting slips of staff members are sometimes processed by the department, instead of by each individual voting member. This kind of practice should be discouraged.

With the participation of women doctors in all the committees, there will be opportunities to establish career development for female physicians and surgeons, to make rules that suit the unique lifestyle of women doctors in academic medicine, and to improve their work-life balance.

Age structures of male and female faculty members with medical license employed by Tokyo Women’s Medical University as of April 1, 2013.

A: Whole Tokyo Women’s Medical University (TWMU). The phenomena of “glass ceiling” and “leaky pipeline” are obvious. When women and men are compared with respect to the youngest age in each academic rank for assistant professor and above, a difference in speed of promotion between men and women is detected. Original figure was published in Tomizawa et al. (2014a) and is reproduced with permission. B: Faculty members in departments utilizing operating rooms, such as surgery, anesthesiology, otorhinology, otolaryngology, dermatology, ophthalmology, urology, obstetrics and gynecology. For female faculty members in the departments that use the operating room, leaky pipeline is obvious. C: Faculty members in surgical specialties affiliated with Japan Surgical Society (JSS) (all surgical specialties excluding brain surgery, orthopedic surgery or plastic surgery). There are few role models for young female surgeons in specialties affiliated with JSS. D: Faculty members in the departments of internal medicine in TWMU. In internal medicine departments, the numbers of men and women faculty members are about equal up to 42-43 years of age. Thereafter, the number of women decreases sharply.

Others: include part-time medical doctors but do not include assistant or nursing staff. DC indicates department chair; Pr, professor; Aso Pr, associate professor; Lec, lecturer; Jr Lec, junior lecturer; Asi Pr; assistant professor, Sr R; senior resident, Jr R; junior resident.

Numbers of female members, councilor and director in Japan Surgical Society.

*a woman councilor by election system.

**a woman councilor by councilor nomination system.

The author has no conflict of interest.