2019 Volume 248 Issue 1 Pages 37-43

2019 Volume 248 Issue 1 Pages 37-43

The antibodies targeting programmed death 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) have provided survival benefits in patients with advanced malignant melanoma. The anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab are considered superior to the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab as first-line therapy, suggesting that ipilimumab should be administered to patients with anti-PD-1 antibody-refractory melanoma in the second-line setting. However, there is limited evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab after disease progression on anti-PD-1 antibody therapy. Moreover, in patients with mucosal melanoma, a rare and aggressive subtype, evidence is extremely poor. This study aimed to clarify the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab among Japanese patients with nivolumab-refractory advanced mucosal melanoma. We retrospectively analyzed the seven patients with advanced mucosal melanoma who were treated with ipilimumab after disease progression on nivolumab at our hospital between September 2015 and December 2017. No patient achieved complete response or partial response to ipilimumab therapy. However, six patients achieved stable disease, and of these patients, three achieved a decline in the tumor size. All the three patients with a decline in tumor size developed grade 3 toxicity: two patients developed colitis and one patient experienced alanine aminotransferase elevation. The median progression-free survival (PFS) for prior nivolumab therapy was 148 days. The median PFS for ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab was 193 days. The median overall survival was 661 days. In conclusion, although even partial response was undetectable with ipilimumab therapy, ipilimumab could produce additional PFS among nivolumab-refractory advanced mucosal melanoma patients.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have improved survival outcomes in patients with advanced melanoma and have greatly impacted the treatment of melanoma and many other types of cancers. In the treatment of advanced malignant melanoma, two kinds of immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting either programmed death 1 (PD-1) or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) are now available (Hodi et al. 2010; Robert et al. 2015). Recent studies have reported that the anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab and pembrolizumab are superior to the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab as first-line therapy (Larkin et al. 2015; Postow et al. 2015). These findings indicate that ipilimumab should be administered in the second-line setting, mainly for nivolumab-refractory melanoma. However, there is limited evidence for the efficacy and toxicity of ipilimumab after disease progression with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy (Bowyer et al. 2016; Fujisawa et al. 2018). A previous study reported that the efficacy of the planned switch therapy of nivolumab followed by ipilimumab is superior to that of the reverse switch therapy of ipilimumab followed by nivolumab. In this previous study, elevated toxicity was also reported in nivolumab followed by ipilimumab therapy (Weber et al. 2016).

Mucosal melanoma is rare and accounts for approximately 1% of all melanomas (Chang et al. 1998). Generally, patients with mucosal melanoma have different genetic and molecular abnormalities and worse prognoses when compared with patients with cutaneous melanoma (Wilkins and Nathan 2009). Furthermore, the efficacy of nivolumab has been reported to be lower in patients with mucosal melanoma than in those with cutaneous melanoma, with progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.0 and 6.2 months, respectively (D’Angelo et al. 2017).

Several small-scale retrospective studies have reported the efficacy of nivolumab alone, ipilimumab alone, or a combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab in patients with non-cutaneous melanoma (Postow et al. 2013; Del Vecchio et al. 2014; D’Angelo et al. 2017). However, there is very limited evidence for ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy (Bowyer et al. 2016; Imafuku et al. 2017). The present study aimed to clarify the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in Japanese patients with nivolumab-refractory advanced mucosal melanoma. We present a case series of seven Japanese patients with mucosal melanoma who received ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapy.

We retrospectively identified patients with advanced mucosal melanoma who had sequentially received ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapy in the Department of Medical Oncology, Tohoku University Hospital, Sendai, Japan. Patients who switched to ipilimumab therapy as part of the treatment plan were not included in this study. The following patient data were collected: age; sex; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS); primary and metastatic sites; mutation status of the BRAF gene; prior therapies; number of nivolumab cycles; response and adverse events (AEs) with nivolumab therapy; and time interval between the last dose of nivolumab and the initial dose of ipilimumab. Nivolumab was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks because of regulatory approval during this analysis in Japan. Ipilimumab was administered at a standard dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks up to a maximum of four doses. To compare clinical outcome of patients who received immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy with that of patients who received conventional chemotherapy, patients with mucosal melanoma who received chemotherapy before approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors were additionally analyzed. The response was evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1. AEs were assessed and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v4.0. Statistical analyses for clinical outcomes were performed using JMP Pro13 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Tohoku University School of Medicine.

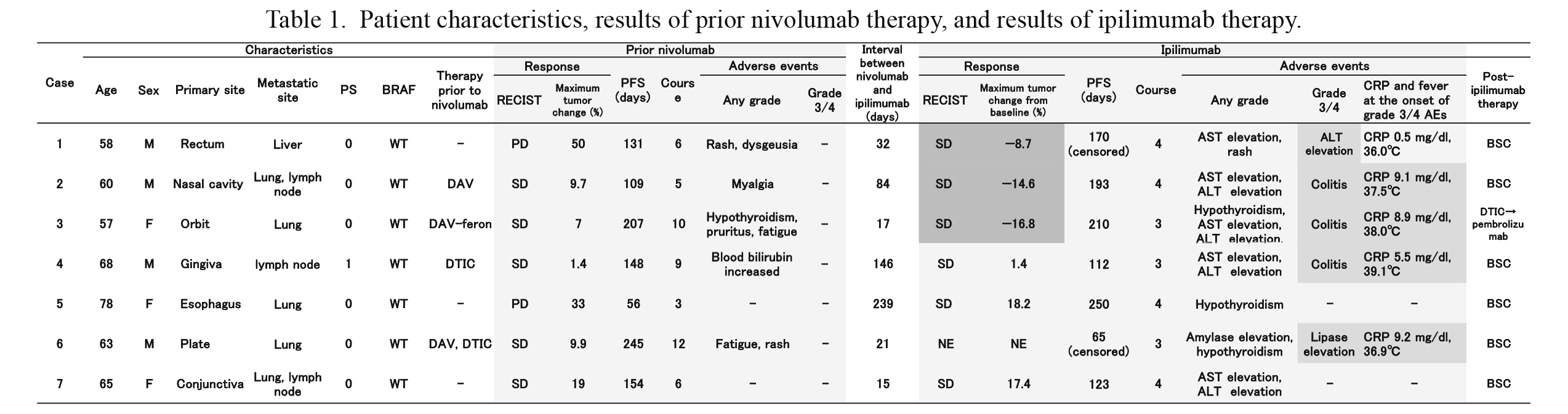

A total of seven Japanese patients (four male and three female patients) were enrolled in this study between September 2015 and December 2017. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median age of the study patients was 63 years. All seven patients had a good ECOG PS of 0 or 1. Each patient had a different mucosal primary site (rectum, orbit, nasal cavity, gingiva, esophagus, palate, or conjunctiva). The metastatic sites were the lungs in five cases, lymph nodes in two cases, and liver in one case. BRAF V600 mutation was not detected in any of the patients. All patients received nivolumab directly before ipilimumab and four patients received dacarbazine (DTIC)-based chemotherapy before nivolumab. As the post ipilimumab therapy, one patient received chemotherapy with DTIC and then pembrolizumab. The remaining cases received best supportive care.

Efficacy and safety of prior nivolumab therapyAll patients received nivolumab at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks owing to the analysis period. In Japan, the standard dose of nivolumab for melanoma patients has been changed to 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks and further changed to 240 mg every 2 weeks since August 2018. The median duration of nivolumab therapy was six courses. Five patients achieved stable disease as the best overall response, whereas the remaining two patients showed disease progression (Table 1). The median PFS was 148 days, and no severe AEs (grade 3/4) were observed (Table 1).

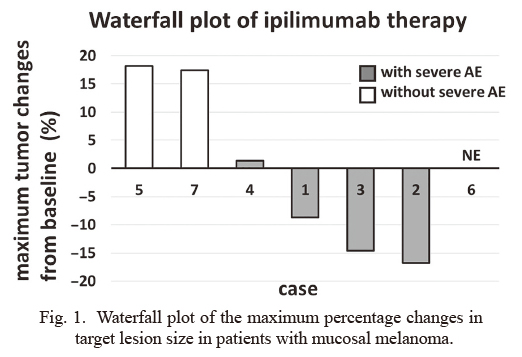

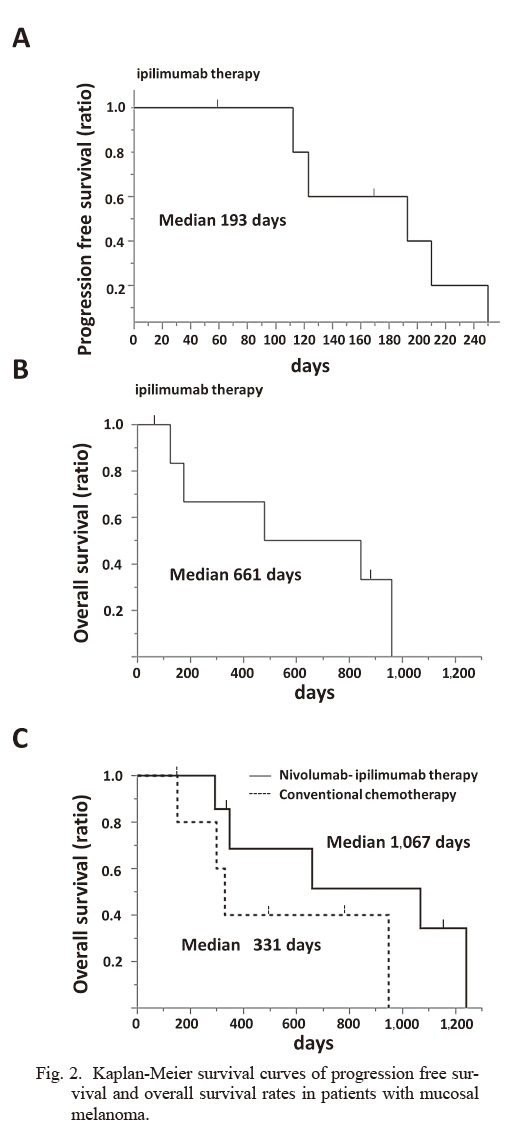

Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapyOnly four patients received all four doses of ipilimumab. The remaining three patients received only three doses owing to toxicity or poor general condition. The median interval between the last dose of nivolumab and the initial dose of ipilimumab was 32 days (range: 15-257 days). No patient achieved complete response or partial response (response rate: 0%). Six patients achieved stable disease, and of these patients, three achieved a decline in the tumor burden (Table 1, Fig. 1). The median PFS was 193 days (Fig. 2A), and the median overall survival was 661 days (Fig. 2B). The median overall survival from the initiation of prior nivolumab therapy was 1,067 days (Fig. 2C). To compare the clinical outcome of this cohort with that of patients who received conventional chemotherapy, patients with advanced mucosal melanoma who received chemotherapy before approval of the immune checkpoint inhibitors were retrospectively analyzed. Six patients who received DTIC-based chemotherapy between April 2008 and June 2013 were identified. The median PFS of these patients was 92 days, and the median overall survival was 331 days (Fig. 2C).

All seven patients developed immune-related AEs (Table 1), and five patients (71.4%) developed grade 3/4 AEs. Four patients (57.1%) developed aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations as the most common toxicities. Three patients (42.9%) developed grade 3 colitis and required hospitalization for more than one month. In these three patients, colitis was accompanied by high fever and high C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, consistent with a previous report (Imafuku et al. 2017). All three patients who achieved a decline in the tumor burden developed grade 3 immune-related AEs (two patients developed colitis and one experienced ALT elevation) (Fig. 1, Table 1). No evident association was found between prior nivolumab therapy outcomes (PFS and treatment course) and response and AEs with ipilimumab therapy. Although an interval of less than 30 days between the final dose of nivolumab and the initial dose of ipilimumab has been reported to increase the risk of severe AEs (Imafuku et al. 2017), the duration was not related to response and AEs with ipilimumab therapy in this study. An overview of the treatment periods is summarized in Fig. 3.

Patient characteristics, results of prior nivolumab therapy, and results of ipilimumab therapy.

The results of prior nivolumab therapy and ipilimumab therapy are shown. The response with a decline in the tumor burden and grade 3/4 adverse events are shown on dark gray background.

M, male; F, female; PS, performance status; WT, wild type; PFS, progression-free survival; SD, stable disease; NE, not evaluated; AE, adverse event; DAV, DTIC + ACNU + VCR; DAV-feron, DTIC + ACNU + VCR + IFN-B; BSC, best supportive care.

Waterfall plot of the maximum percentage changes in target lesion size in patients with mucosal melanoma.

The graph shows the maximum percentage changes in target lesion size from baseline in seven patients with mucosal melanoma who received ipilimumab after disease progression with nivolumab therapy. Responses are evaluated according to RECIST 1.1. Patients who developed severe AEs (grade 3/4) are depicted by gray columns. Patients who did not develop severe AEs are depicted by white columns.

AE, adverse event; NE, not evaluated.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of progression free survival and overall survival rates in patients with mucosal melanoma.

A) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of progression free survival rate in seven patients who received ipilimumab after disease progression with nivolumab therapy.

B) Kaplan-Meier survival curve of overall survival rate in seven patients who received ipilimumab after disease progression with nivolumab therapy.

C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival rates in seven patients who received nivolumab-ipilimumab therapy and six patients who received conventional DTIC based chemotherapy, respectively.

Swimmer plot of the treatment durations of nivolumab therapy and ipilimumab therapy.

AE, adverse event; PD, progressive disease.

We present two cases from Table 1 in which we observed tumor shrinkage with ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapy.

Case 2: The patient was a 60-year-old man diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the left nasal cavity with wild-type BRAF. He was treated with heavy particle radiotherapy and sequential chemotherapy (DAV: DTIC + ACNU + VCR). Two years later, follow-up computed tomography (CT) showed a mediastinal lymph node and lung metastasis, and then, he visited our department. Nivolumab was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks for 15 weeks. During nivolumab therapy, he developed grade 1 myalgia without elevation of creatine phosphokinase. After the fifth administration of nivolumab, follow-up CT suggested progression of lymph node metastasis. During a 12-week interval, the lymph node metastasis progressed further, and then, ipilimumab was administered at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks. After the third administration of ipilimumab, AST and ALT levels increased up to thrice the normal range. Both levels normalized by conservative treatment without steroids. Then, ipilimumab was administered for the fourth time. Follow-up CT showed decreased mediastinal lymph node metastasis (Fig. 4A). However, one week after the last administration of ipilimumab, he developed grade 3 diarrhea with CRP elevation. CT scan showed bowel fluid collection. He was diagnosed with immune-related colitis, and he received methylpredonisolone sodium succinate (1 mg/kg/day) intravenously with appropriate reduction. His diarrhea and CRP elevation promptly improved without recurrence. The PFS with ipilimumab was 193 days (Table 1).

Case 3: The patient was a 57-year-old woman who was diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the right orbit. She underwent right orbital exenteration followed by chemoradiotherapy (DAV-feron combined with 45 Gy radiotherapy). Three years later, follow-up CT showed a single lung tumor in the upper lobe of the left lung. Thoracoscopic partial resection of the left lung was performed for the tumor. The tumor was pathologically confirmed as metastatic malignant melanoma with wild-type BRAF. Only one month after the surgery, a new lung metastasis was noted in the left remnant lung. Nivolumab was administered at a dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks. During nivolumab therapy, the tumor size did not change. After the tenth administration of nivolumab, lung metastasis progression was observed on follow-up CT. Ipilimumab was administered at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks, with a 17-day interval since the last dose of nivolumab. Ten days after the second administration of ipilimumab, she visited our hospital because of high fever and fatigue. Laboratory findings showed a four-fold increase in AST and ALT levels (grade 2). She received oral prednisolone (0.5 mg/kg/day), and subsequently, the AST and ALT levels smoothly decreased and normalized. Ipilimumab was administered for the third time, with a one-week delay in the schedule. One week later, she developed watery diarrhea, abdominal pain, and high fever (temperature over 38.0°C). CRP level was elevated up to 8.9 mg/dl (Table 1). CT scan did not show definitive finding of colitis, but showed shrinkage of lung metastasis (Fig. 4B). After excluding infection, she empirically received methylpredonisolone sodium succinate (1 mg/kg/day) intravenously. Although her colitis symptoms transiently improved, they worsened again. Steroid pulse therapy with methylpredonisolone sodium succinate (500 mg/day/body) was performed for 3 days. Colonoscopy performed at that time showed multiple cecal ulcerations, and biopsy findings showed inflamed mucosa. Thus, she was diagnosed with immune-related severe colitis. Following the steroid pulse therapy, her colitis improved, and no recurrence of colitis was noted during steroid taper. The PFS with ipilimumab was 210 days (Table 1).

Changes in metastatic lesions of malignant melanoma before and after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy on computed tomography.

A) Case 2: A 60-year-old man diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the left nasal cavity with mediastinal lymph node metastasis.

B) Case 3: A 57-year-old woman diagnosed with malignant melanoma of the right orbit with lung metastasis.

Although recent studies have shown that the combination of an anti-PD-1 antibody and the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab is more effective than monotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma, the combination therapy is more toxic than monotherapy (Larkin et al. 2015; Postow et al. 2015). Immune-related AEs are sometimes lethal or require long-term hospitalization (Abdel-Rahman et al. 2017). Thus, monotherapy of an immune checkpoint inhibitor with a lower incidence of AEs remains a possible treatment strategy. Anti-PD-1 antibody monotherapy has been found to be superior to ipilimumab monotherapy as a first-line therapy, suggesting that ipilimumab should be administered to patients with anti-PD-1 antibody-refractory melanoma in the second-line setting (Larkin et al. 2015; Postow et al. 2015). However, the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab after disease progression with anti-PD-1 antibody therapy have not been established in patients with cutaneous melanoma and especially in patients with mucosal melanoma owing to its rarity. Mucosal melanoma exhibits genetic and molecular abnormalities that differ from those of cutaneous melanoma (Wilkins and Nathan 2009). The incidence of mucosal melanoma has been reported to be higher in the Asian population than in the Caucasian population (D’Angelo et al. 2017). Therefore, it is meaningful to evaluate the strategy of using two kinds of immune checkpoint inhibitors, which provides better efficacy and safety in Japanese patients with mucosal melanoma. Thus, in this study, we evaluated ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapy in Japanese patients with mucosal melanoma.

With regard to immune checkpoint inhibitor treatments for mucosal melanoma patients, a pooled analysis of retrospective studies reported that the median PFS durations in patients with mucosal melanoma who received nivolumab alone, ipilimumab alone, and the combination of nivolumab and ipilimumab were 3.0, 2.7, and 5.9 months, respectively, with objective response rates of 23.3%, 8.3%, and 37.1%, respectively (D’Angelo et al. 2017). In our study, the median PFS for prior nivolumab therapy was 148 days (4.9 months), and the PFS for ipilimumab therapy after disease progression with nivolumab therapy was 193 days (6.4 months). Despite its use as a second-line therapy, the PFS with ipilimumab therapy was superior to that with prior nivolumab therapy. Although the response rate of ipilimumab according to the RECIST was 0%, tumor volume shrinkage was observed in three cases. These results indicate that ipilimumab might produce additional PFS after disease progression with nivolumab therapy but might not be associated with a response. In our study, all three patients who showed a decline in the tumor burden developed grade 3 immune-related AEs (Table 1). This result is consistent with previous findings that the development of immune-related AEs is associated with clinical benefits in patients with melanoma (Freeman-Keller et al. 2016; Fujii et al. 2018). With regard to toxicity, in our study, the frequency of grade 3/4 AEs in patients treated with ipilimumab was 71.4%, which is higher than the frequency for combination therapy involving nivolumab and ipilimumab (40.0%) reported in a previous study (D’Angelo et al. 2017). These findings indicate that ipilimumab might improve PFS, even after disease progression with nivolumab therapy in patients with mucosal melanoma. However, the incidence of grade 3/4 AEs can be up to or can exceed that of combination therapy.

Fujisawa et al. (2018) reported the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab after nivolumab therapy in 60 Japanese melanoma patients; however, their study included both cutaneous and non-cutaneous melanoma patients. The authors reported that the objective response rate of ipilimumab was 3.6% and the incidence of grade 3/4 AEs was 70%, and they concluded that the benefit was unsatisfactory (Fujisawa et al. 2018). Although in this previous study, the response rate and median overall survival time (223 days, 7.4 months) were reported, PFS was not mentioned. We emphasize that second-line ipilimumab therapy might bring PFS almost equal to that with prior nivolumab therapy, and might lead to prolonged overall survival. The median overall survival from the initiation of ipilimumab therapy and from prior nivolumab therapy was 661 days (22.0 months) and 1,067 days (35.6 months), respectively (Fig. 2B and C). Additionally, the results of comparison of overall survival rates showed improvement of treatment efficacy by immune check point inhibitors (Fig. 2C).

The present study has some limitations. First, only seven patients were enrolled. As the study had a small number of patients and included retrospective data, we could not confirm the efficacy and safety of ipilimumab after disease progression with nivolumab therapy in Japanese mucosal melanoma patients. However, our results are consistent with the findings of a previous larger study with regard to the extremely low response rate and increased frequency of immune-related AEs (Fujisawa et al. 2018). Second, low-dose nivolumab (2 mg/kg every 3 weeks) was used in this study. After the study period, the approved dose of nivolumab in Japan was changed to 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks and further changed to 240 mg flat dose every 2 weeks. Some studies have reported relations between the dose of nivolumab and its efficacy and safety. In these studies, the efficacy and safety profiles were similar across nivolumab doses (Agrawal et al. 2016, Zhao et al. 2017). In our study, neither response nor grade 3/4 AEs were observed with prior nivolumab therapy. On the other hand, a previous report showed that nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks achieved a response rate of 23.3% and showed a grade 3/4 AE rate of 8.1% in mucosal melanoma patients (D’Angelo et al. 2017). Although we cannot conclude whether the difference depends on the dose of nivolumab, these results are not in accordance with dose response analysis data (Agrawal et al. 2016; Zhao et al. 2017). However, we have focused on the result that ipilimumab caused severe immune-related AEs at a high frequency even after low-dose nivolumab therapy.

In conclusion, our study indicated that ipilimumab might show therapeutic benefits even in patients with nivolumab-refractory advanced mucosal melanoma. However, severe grades of immune-related AEs are likely to occur at an increased frequency. Ipilimumab therapy after nivolumab therapy warrants close surveillance of immune-related AEs. Prospective clinical studies are needed to evaluate whether second-line use of ipilimumab after disease progression with nivolumab therapy or combination therapy involving these two drugs is more beneficial.

Chikashi Ishioka has received contributions from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Eisai Co., Ltd. Chikashi Ishioka is a representative of Tohoku Clinical Oncology Research and Education Society, a specified non-profit corporation. Masanobu Takahashi has received research funding from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Shin Takahashi has received research funding from Merck Serono Company and received lecture fee from Asahi Kasei Pharma Corporation.

The other authors report no conflict of interest in the present study.