2024 Volume 262 Issue 4 Pages 229-238

2024 Volume 262 Issue 4 Pages 229-238

Specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed (SMART) principle improves the nursing utility by setting individual goals for participants and helping them to achieve these goals. Our study intended to investigate the impact of a SMART nursing project on reducing mental stress and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients. In this randomized, controlled study, 66 childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients and 126 corresponding parents were enrolled and divided into SMART or normal care (NC) groups at a 1:1 ratio. All parents received a 3-month corresponding intervention and a 6-month interview. Our study revealed that the self-rating anxiety scale score at the 3rd month (M3) (P < 0.05) and the 6th month (M6) (P < 0.01), and anxiety rate at M3 (P < 0.05) and M6 (P < 0.05) were lower in parents in SMART group vs. NC group. The self-rating depression scale score at M3 and M6, and depression rate at M3 and M6 were lower in parents in SMART group vs. NC group (all P < 0.05). Impact of events scale-revised score at the 1st month (M1) (P < 0.05), M3 (P < 0.05), and M6 (P < 0.01) were lower in parents in SMART group vs. NC group. By subgroup analyses, the SMART nursing project showed better impacts on decreasing anxiety, depression, and PTSD in parents with an undergraduate education or above than in those with a high school education or less. Conclusively, SMART nursing project reduces anxiety, depression, and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients, which is more effective in those with higher education.

Osteosarcoma is a malignant bone tumor with an annual incidence rate of about 2-5 per million population, which is manifested as local pain, local swelling, and dysfunction of joint movement (Biazzo and De Paolis 2016; Zhao et al. 2021; Urlic et al. 2023). Notably, the peak population of osteosarcoma is children and adolescents, which not only adversely affects patients themselves, but also causes huge burdens to their parents (Pohlig et al. 2017; Belayneh et al. 2021; Lee et al. 2021). Evidence shows that the parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients usually suffer from a series of psychological issues, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Yonemoto et al. 2012; Meng et al. 2022). Therefore, it is extremely crucial to focus on mental stress and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients.

Providing high-quality nursing methods for parents of childhood or adolescent cancer patients is a critical approach to alleviating their mental stress and PTSD (Kearney et al. 2015; Wiener et al. 2015; Eche et al. 2021). Notably, only one study puts forward a WeChat-platform-based education and care program for parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients; this program achieves real-time communication and information sharing with parents through WeChat groups (Wu et al. 2022). Specifically, the WeChat-platform-based education and care program establishes a series of interventions (including health guidance and education on discharge, information transfer and communication, information database, and online education and counseling) to effectively decrease anxiety and depression in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients (Wu et al. 2022). Whereas, this previous study exhibits a limited relief effect on PTSD (Wu et al. 2022). Therefore, more effective nursing methods need to be established for parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients.

The specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed (SMART) principle is proposed by management master Peter Drucker, which helps people set goals and achieve them (Bovend’Eerdt et al. 2009; Lu et al. 2022). In detail, goal setting and goal achievement make things more manageable, enable people to feel supported, and motivate them to be positive to take action, which realizes long-term improvement in mental functioning (Preede et al. 2021; Jacob et al. 2022; Lu et al. 2022). One study illustrates that an intervention involving goal setting decreases PTSD symptoms in veterans (Brief et al. 2013). Another study also reveals that the application of goal setting and goal achievement improves mental health and physical activity in patients after high tibial osteotomy (Hiraga et al. 2021). Thus, integrating SMART principles into the nursing method may be effective for relieving mental stress and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients. However, there is currently no relevant research.

Therefore, this study designed a nursing project involving SMART principles, aiming to compare the impact of the SMART nursing project intervention vs. the normal care (NC) intervention on mental stress and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients.

This randomized, controlled study enrolled 66 childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients and 126 corresponding parents from August 2018 to February 2022. Six of the patients were from single-parent families. The inclusion criteria were: i) patients were diagnosed with osteosarcoma by pathohistological and/or cytological methods; ii) patients’ age was under 20 years; iii) patients underwent tumor resection; iv) parents were willing to cooperate with this study and complete relevant scales. The exclusion criteria were: i) patients with other tumors; ii) parents with histories of drug and/or alcohol abuse; iii) parents who could not complete relevant scales, such as documented mental disorders or illiterate. The Ethics Committee of First Affiliated Hospital, Heilongjiang University of Chinese Medicine approved this study. All the subjects signed the informed consent.

RandomizationAfter the operation, the subjects were divided into SMART or NC groups at a 1:1 ratio by block random method based on the patient. The block size was set as 4. The sealed and opaque envelopes with the patient’s ID on the cover were used for random group assignments. The trained nurse opened the envelope to confirm and recorded the grouping information.

GroupsA total of 33 patients and 64 corresponding parents were assigned to the SMART group; meanwhile, 33 patients and 62 corresponding parents were assigned to the NC group. Parents in the SMART group received the ‘propaganda and education’ plus a ‘SMART nursing project,’ while parents in the NC group only received the ‘propaganda and education.’

Propaganda and educationAfter the operation, unified propaganda and education were conducted on parents by the trained nurses. The content included as follows: 1) disease-related: mainly focused on the definition and types of osteosarcomas; 2) diet-related: paid attention to dietary contraindications, such as avoiding spicy food and seafood; 3) rehabilitation-related: mainly included teaching how to recover joint function; and 4) post-operative precautions: mainly contained how to monitor vital signs, observe wound swelling, and prevent infections. After discharge, weekly telephone calls were conducted until the 3rd month (M3) to answer questions for parents.

SMART nursing projectThe SMART nursing project continued for 3 months. The intervention covered the following five main areas (Bexelius et al. 2018): 1) S (Specific): The researchers informed the parents that the intervention was designed to help them improve their mental condition and post-traumatic stress reaction. 2) M (Measurable): The psychological condition and post-traumatic stress reaction of the parents were assessed through the self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), self-rating depression scale (SDS), and impact of events scale-revised (IES-R) scale (Zung 1965, 1971; Creamer et al. 2003). 3) A (Attainable): Attainable mini-goals were set according to the actual situation of the parents. The mini-goals involved as follows: a) parents took a walk every day, b) parents listened to pleasant rhythm songs every day, c) parents talked to families or friends every day, and d) parents did mental relaxation exercises every day under the guidance of the psychologists, etc. 4) R (Relevant): Each parent set a mini-goal that suited him/her and that he/she most wanted to achieve, then the trained nurses gave daily telephone call to monitor the parent accomplishing it by punching card records. Except for those mini-goals, 30-minute psychological counseling to the parent was conducted by researchers in the form of a telephone call once a week, and the researchers gave psychological guidance or changed the mini-goals as appropriate (based on the parents’ actual situation or their wishes). 5) T (Time-based): The achievement of the mini-goals was completed in a time period-based condition. For example, parents insisted on taking a walk every day for 30 minutes; parents insisted on listening to pleasant rhythm songs every day for 15 minutes; parents insisted on talking to families or friends as least 20 minutes every day; and parents did mental relaxation exercises for 20 minutes every day under the guidance of the researchers.

Data collectionAge, sex, disease-related features, and surgery type were collected from the osteosarcoma patients. The relation to patients, demographics, and comorbidities were collected from their corresponding parents as well.

Outcome measurementParents were followed up for 6 months. Outpatient follow-up was conducted during the first 3 months after discharge, and thereafter by telephone. The SAS, SDS, and IES-R scales were assessed at enrollment (M0), the 1st month (M1), and the 6th month (M6) after discharge. The total score for both SAS and SDS was 100, parents with higher SAS and SDS scores were behaving with more anxiety and more depression, respectively. The SAS score of equal to or more than 50 was denoted anxiety, and the SDS score was used to denote depression by the same rules (Guo and Huang 2021). The total score for IES-R was 88, and parents with a higher score of IES-R were suffering from severer parental PTSD. The SAS score at M6 was considered the primary outcome, and the other scores assessed in the study were considered secondary outcomes.

Sample size calculationBased on the clinical experience, a hypothesis of the SAS score at M6 of parents was raised, in which the mean score of the SMART group and the NC group was 45.0 and 55.0, respectively; and the standard deviation (SD) was 10.0. The α was 0.05 and 1-β was 95%. As a result, 27 patients in each group (the minimized sample size) were calculated. Considering 20% of the dropout rate, 33 patients for each group (a total of 66) were finally determined.

Statistical analysesSPSS v.26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data processing. Comparison analyses between the two groups were performed by student t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, Chi-squared test, or Fisher’s exact test appropriately. All statistical analyses were using a two-sided test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 78 osteosarcoma patients and 150 corresponding parents were enrolled, among which 12 patients and their 24 parents were excluded. The remaining 66 eligible and 126 corresponding parents were randomized at a 1:1 ratio according to patients into the SMART group (33 patients and 62 corresponding parents) and NC group (33 patients and 64 corresponding parents). Then, parents in the SMART group received the propaganda and education plus a SMART nursing project for 3 months, and parents in the NC group received the propaganda and education for 3 months. All parents in the two groups were followed up for 6 months. SAS, SDS, and IES-R scores were evaluated in parents of both groups at M0, M1, M3, and M6. All parents in both groups were included in the analysis based on the intention-to-treat principle (Fig. 1).

Study flow chart.

SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed; NC, normal care; SAS, self-rating anxiety scale; SDS, self-rating depression scale; IES-R, impact of events scale-revised; M1, the 1st month after discharge; M3, the 3rd month after discharge; M6, the 6th month after discharge; ITT, intention-to-treat.

The patients in the SMART group had a mean age of 10.8 ± 3.4 years (mean ± SD), comprised of 13 (39.4%) females and 20 (60.6%) males. Meanwhile, the patients in the NC group had a mean age of 11.7 ± 3.5 years, comprised of 9 (27.3%) females and 24 (72.7%) males. In terms of parents, the SMART group contained 32 (51.6%) mothers and 30 (48.4%) fathers, whose mean age was 40.2 ± 4.8 years. The NC group contained 32 (50.0%) mothers and 32 (50.0%) fathers, whose mean age was 40.9 ± 5.2 years. All baseline characteristics of patients or parents were not different between groups (all P > 0.05). A more specific description of traits in both groups was shown in Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed; NC, normal care; SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization; CNY, Chinese yuan.

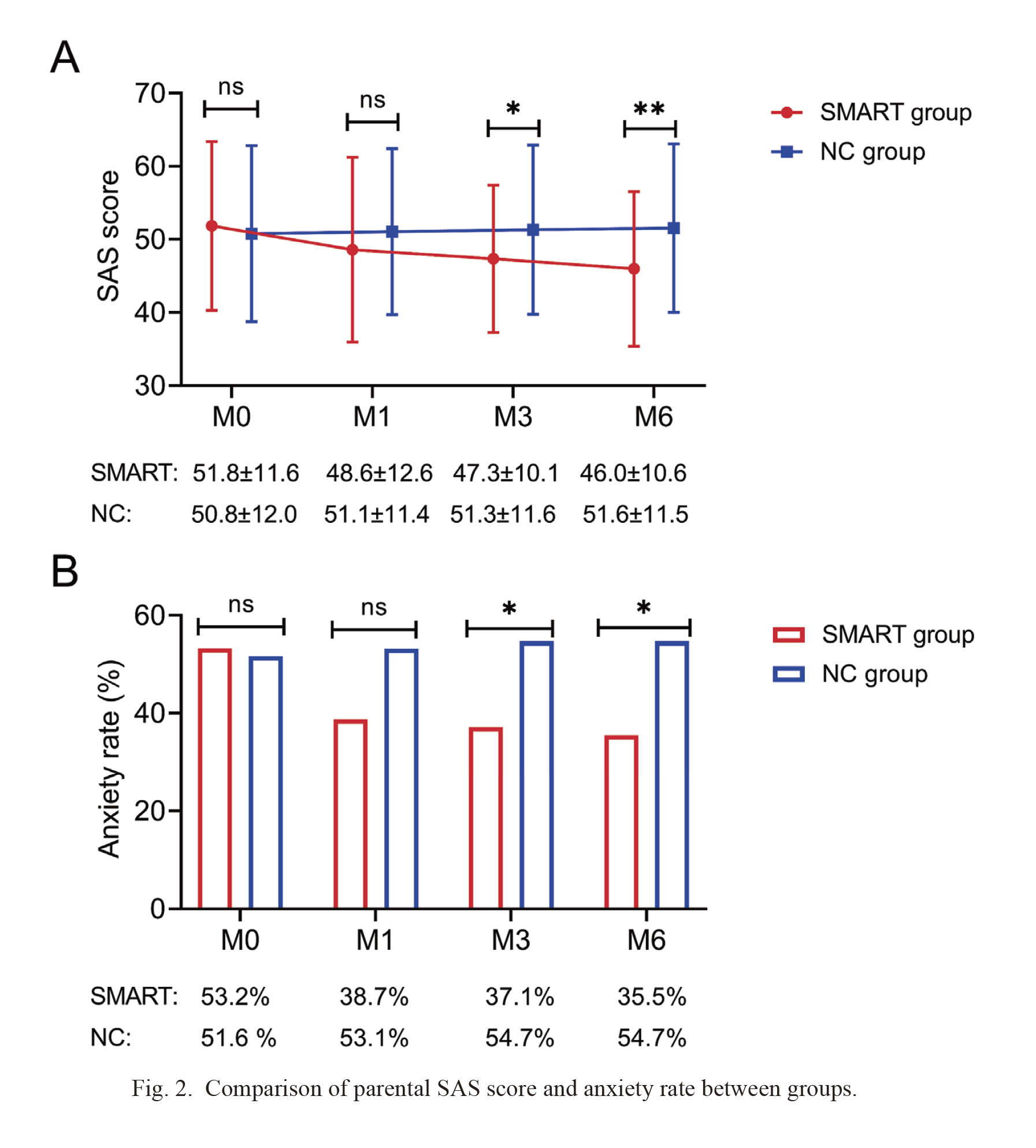

During the follow-up period, there were 7 parents of 4 osteosarcoma patients who dropped out in the SMART group, and 12 parents of 6 osteosarcoma patients who dropped out in the NC group. The SAS score at M3 (47.3 ± 10.1 vs. 51.3 ± 11.6) (P < 0.05) and M6 (46.0 ± 10.6 vs. 51.6 ± 11.5) (P < 0.01) were observed to be lower in parents in the SMART group compared to those in the NC group (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the anxiety rate at M3 (37.1% vs. 54.7%) (P < 0.05) and M6 (35.5% vs. 54.7%) (P < 0.05) were also lower in parents in the SMART group when compared with those in the NC group (Fig. 2B).

The SDS score at M3 (46.0 ± 10.0 vs. 50.2 ± 10.9) (P < 0.05) and M6 (45.7 ± 11.5 vs. 49.6 ± 9.3) (P < 0.05) were lower in parents in the SMART group vs. those in the NC group (Fig. 3A). The depression rate at M3 (32.3% vs. 53.1%) (P < 0.05) and M6 (30.6% vs. 50.0%) (P < 0.05) were lower in parents in the SMART group compared with those in the NC group (Fig. 3B).

Comparison of parental SAS score and anxiety rate between groups.

Parental SAS score (A) and anxiety rate (B) at M3 and M6 were lower in the SMART group compared to the NC group. M0, at enrollment; M1, the 1st month after discharge; M3, the 3rd month after discharge; M6, the 6th month after discharge; ns, no significance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Comparison of parental SDS score and depression rate between groups.

Parental SDS score (A) and depression rate (B) at M3 and M6 were lower in the SMART group compared to the NC group. M0, at enrollment; M1, the 1st month after discharge; M3, the 3rd month after discharge; M6, the 6th month after discharge; ns, no significance. *P < 0.05.

The IES-R score at M1 [median interquartile range (IQR): 14.5 (10.0-25.0) vs. 17.0 (15.0-27.0)] (P < 0.05), M3 [median (IQR): 12.5 (9.8-21.3) vs. 16.0 (12.0-25.0)] (P < 0.05), and M6 [median (IQR): 11.0 (6.0-18.0) vs. 15.0 (11.0-23.5)] (P < 0.01) were lower in parents in the SMART group when compared to those in the NC group (Fig. 4).

Comparison of parental IES-R score between groups.

Parental IES-R score at M1, M3, and M6 were lower in the SMART group compared to the NC group. M0, at enrollment; M1, the 1st month after discharge; M3, the 3rd month after discharge; M6, the 6th month after discharge; ns: no significance. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

In parents with an undergraduate education or above, the SAS score at M3 (47.5 ± 8.1 vs. 53.8 ± 11.2) (P = 0.015) and M6 (46.5 ± 8.5 vs. 54.2 ± 11.2) (P = 0.004), as well as anxiety rate at M6 (35.5% vs. 66.7%) (P = 0.015) were lower in the SMART group compared to NC group. The SDS score at M3 (46.1 ± 9.8 vs. 51.8 ± 10.5) (P = 0.033) and M6 (45.7 ± 10.5 vs. 51.2 ± 8.9) (P = 0.032), as well as depression rate at M3 (32.3% vs. 60.0%) (P = 0.030), were lower in the SMART group vs. NC group. Moreover, the IES-R score at M6 was also lower in the SMART group when compared with the NC group [median (IQR): 13.0 (7.0-18.0) vs. 15.5 (10.8-49.3)] (P = 0.023) (Table 2).

By contrast, in parents with a high school education or less, no discrepancy was found in the SAS score, anxiety rate, SDS score, or depression rate at any assessment timepoint between groups (all P > 0.05). Only the IES-R score at M6 was lower in the SMART group compared to the NC group [median (IQR): 8.0 (6.0-20.0) vs. 14.0 (10.8-15.3)] (P = 0.041) (Table 2).

Subgroup analyses of parents.

SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, timed; NC, normal care; SAS, self-rating anxiety scale; SD, standard deviation; M0, at enrollment; M1, the 1st month after discharge; M3, the 3rd month after discharge; M6, the 6th month after discharge; SDS, self-rating depression scale; IES-R, impact of events scale-revised; IQR, interquartile range.

Anxiety, depression, and PTSD are common psychological issues for parents of childhood or adolescent cancer patients, especially in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients (van Warmerdam et al. 2019; Gurtovenko et al. 2021; Meng et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022). For example, one recent study illustrates that baseline anxiety and depression rates were 56.1%-56.8% and 40.9%-41.5%, respectively, and the median value of the baseline IES-R score was 18.0 in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients (Wu et al. 2022). Another study shows that the baseline anxiety and depression rates were 45.2% and 38.5% in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients (Meng et al. 2022). In our study, the baseline anxiety and depression rates were 51.6%-53.2% and 48.4%-51.6%, and simultaneously, the median value of the baseline IES-R score was 18.0-20.0 in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients. The baseline anxiety and depression rates in our study were slightly different from previous studies, possibly due to the differences in the scale used for assessment (Meng et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022). Nevertheless, all studies have indicated that the psychological problems of parents of childhood or adolescent cancer patients cannot be ignored, and effective intervention methods are required to be established (Meng et al. 2022; Wu et al. 2022).

In our study, the SMART nursing project was proposed based on SMART principles; concretely, it made parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients clearly know the purpose of the intervention, set them some relaxing and attainable mini-goals according to actual situations, and then monitored them to achieve these goals within a fixed time frame. Our study suggested that the SMART nursing project effectively yielded a reduction of anxiety, depression, and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients. These findings might be attributed to several points: (1) The SMART nursing project directly told parents the objectives of nursing intervention, making them know what they should do and take action actively, thus obtaining satisfactory nursing outcomes (Lu et al. 2022). (2) The SMART nursing project formulated some attainable mini-goals for parents, such as walking, listening to music, talking, or doing mental relaxation exercises, which made parents relax physically and mentally, get a sense of well-being, and release negative emotions, thus reducing anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Kim et al. 2013; McCurley et al. 2019; Witusik and Pietras 2019; Nagata et al. 2021). (3) The SMART nursing project engaged parents to complete their goals, which might make them achieve self-worth and obtain positive self-appraisals, thus improving their mental health (Liu and Huang 2018; Engelbrecht and Jobson 2020).

In addition, our study also found that the SMART nursing project exhibited a better effect on reducing anxiety, depression, and PTSD in parents with an undergraduate education or above when compared to those with a high school education or less; that was to say, parents with higher education might benefit more from the SMART nursing project. The specific explanations were as follows: (1) Parents with higher education might adopt systematic knowledge more quickly and be more receptive to SMART principles; thus, they might get a better outcome through the SMART nursing project (Hahn and Truman 2015; Lovden et al. 2020). (2) Parents with higher education might have a higher ability for self-management, and they followed SMART principles to implement the goals set more actively (Lai et al. 2021). Thus, the SMART nursing project might be more effective for parents with higher education.

The strength and novelty of our study was as follows: (1) Our study was a randomized controlled study, and assessed the impacts of SMART nursing project in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients at multiple time points. (2) Our study was the first study involving SMART principles into the nursing method to explore its effect on mental stress and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients. Our study involved several limitations that should be concerned: (1) The sample size of our study was small, and a large sample size should be included in future studies for verification. (2) One previous study reveals that the anxiety and depression rates of parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients persist and rise over time (Meng et al. 2022). However, our study had a short follow-up period of only 6 months. Thus, further studies should explore the long-term effects of the SMART nursing project on those parents. (3) The scales used to assess anxiety, depression, and PTSD were self-assessed scales, which might cause bias in assessment. (4) Our study did not assess anxiety, depression, and PTSD in childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients, and further studies should consider exploring the effect of SMART nursing project in those patients.

In conclusion, the SMART nursing project alleviates anxiety, depression, and PTSD in parents of childhood or adolescent osteosarcoma patients, especially yielding better effects in parents with higher education.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.