Abstract

Approximately 30% of patients with cancer pain experience concurrent neuropathic pain. Since these patients are not sufficiently responsive to morphine, the development of an effective method of pain relief is urgently needed. Decreased function of the μ opioid receptor, which binds to the active metabolite of morphine M-6-G in the brain, has been proposed as a mechanism for morphine resistance. Previously, we pharmacokinetically examined morphine resistance in mice with neuropathic pain, and demonstrated that the brain morphine concentration was decreased, expression level of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) in the small intestine was increased, and expression level and activity of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)2B in the liver were increased. In order to clarify the mechanism of the increased expression of UGT2B, we examined the phase of neuropathic pain during which UGT2B expression in the liver begins to increase, and whether this increased expression is nuclear receptor-mediated. The results of this study revealed that the increased expression of UGT2B in the liver occurred during the maintenance phase of neuropathic pain, suggesting that it may be caused by transcriptional regulation which was not accompanied by increased nuclear import of pregnane X receptor (PXR).

It has been reported that the onset of neuropathic pain is closely associated with the immune response around the damaged nerve. When a nerve is injured, histamine, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines are released from mast cells located in the damaged nerve, inducing the activation and accumulation of neutrophils and macrophages to the nerve site. Subsequently, inflammatory cytokines and chemokines released from the accumulated cells sensitize the primary sensory nerves,1,2) increasing the release of pain transmitters from the primary sensory nerve endings, resulting in an unusual enhancement of the effect of the pain transmitters on secondary sensory nerves.3,4) The effect of pain transmitters on secondary sensory nerves is further augmented by the activation of microglia,5–9) a type of glia cell, in the spinal cord. This accelerates the release of inflammatory cytokines and other factors. It has also been reported that expression of the ligand–gated ion channel pregnane 2 recepter (P2X) receptor is increased in activated microglia.8,10–12) This induces the release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) from microglia, which binds to the tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB) receptor on secondary sensory nerves, downregulating the expression of K-Cl cotransporter 2 (KCC2).13,14) The reduced expression of KCC2 disinhibits GABAergic neurons, which suppress the sensation of pain under normal conditions, resulting in pain enhancement.15) The expression of P2X receptor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor is also increased by interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8), a transcription factor belonging to the interferon regulatory factor family.16)

A recent report states that the activation of astrocytes, another type of glia cell, is also associated with the onset of neuropathic pain.17–20) Microglia and astrocytes play different roles in pain development.21–25) The activity of microglia begins to increase immediately after nerve injury occurs, reaching a peak after 1 week, and then gradually declining.22) In a mouse neuropathic pain model, treatment with a microglia activation inhibitor starting immediately after model preparation suppressed the onset of neuropathic pain.23) In contrast, astrocytes became activated 1 week after nerve injury and were maintained in an activated state for at least 12 weeks.22) In a mouse neuropathic pain model, long-term treatment with an astrocyte activation inhibitor starting immediately after model preparation reduced pain 1 week after nerve injury and later.23) These findings suggest that microglia are involved in the induction of neuropathic pain and that the activation of astrocytes is closely associated with the maintenance of the disease; however, the detailed mechanism of neuropathic pain development remains unclear.

As described above, the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain and the effect of the disease on higher brain function have been widely investigated26–28); however, the effect of neuropathic pain on peripheral organs remains unclear. We previously demonstrated that increased expression of uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)2B in the liver was a major cause of morphine resistance in neuropathic pain.29) The present study focused on nuclear receptors, which have been reported to regulate the expression of UGT2B in the liver. UGT2B expression in the liver is regulated primarily by the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR),30–32) a nuclear receptor and conjugating enzyme most highly expressed in the liver; this receptor is also found in the small intestine. In addition to conjugating enzymes such as UGT2B, metabolizing enzymes such as CYP2B33–35) and transporters such as multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2)36,37) are known to be target genes of CAR. Previous reports have indicated that another nuclear receptor, pregnane X receptor (PXR), also regulates the expression of UGT2B in the liver.38,39) In HepG2 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells, the addition of a ligand of PXR, aflatoxin B1, nearly doubled the mRNA expression level of UGT2B7, which is involved in morphine metabolism in humans, and nearly doubled the mRNA expression level of CYP3A4, a target gene of PXR. PXR shows the highest expression in the liver, with some expression also observed in the small and large intestines.40) The known target genes of PXR are conjugating enzymes such as UGT2B, metabolizing enzymes of the CYP3A subfamily,41,42) and transporters such as P-glycoprotein (P-gp).43–45) PXR shows low ligand specificity and binds to a wide range of chemicals and biological substances. The objective of the present study was to evaluate the effect of neuropathic pain on peripheral organs, in a mouse neuropathic pain model, by examining the phase of the disease in which the expression of UGT2B in the liver increases, and whether this increased expression is nuclear receptor-mediated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal HandlingMale ICR mice (20–25g) were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Tokyo Laboratory Animals Science Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Mice were kept at room temperature (24±1°C) and 55±5% humidity with 12 h of light (artificial illumination; 08:00–20:00). Food and water were available and ad libitum. Each animal was used only once. The present study was conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and use of Laboratory Animals, as adopted by the Committee on Animal Research at Hoshi University.

Neuropathic Pain ModelThe mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane. We produced a partial sciatic nerve injury by tying a tight ligature with a 8-0 silk suture around approximately one-third to one-half the diameter of the sciatic nerve on the right side under a light microscope (SD30, Olympus, Tokyo). In sham-operated mice, the nerve was exposed without ligation. Pain hypersensitivity to a heat stimulus was evaluated in mice with neuropathic pain using a paw flick test or tail flick test (Fruhstorfer et al., 2001; Kallina and Grau, 1995; Keizer et al., 2008; Keizer et al., 2007; Mulder and Pritchett, 2004; Pitcher et al., 1999; Yasphal et al., 1982). Antinociception induced by morphine was determined by tail-flick test (Tail Flick Analgesia Meter Model MK330B, Muromachi Kikai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The intensity of the heat stimulus was adjusted, so that the animal flicked its tail after 3–5 s. When the intensity of stimulation was enough to produce a basal movement within 3–5 s in mice, it was defined that pharmacological observation results from the spinal reflex and supraspinal modulations. The inhibition of this tail-flick response was expressed as a percentage of the maximum possible effect (% MPE), which was calculated as ((T1−T0)×100/(T2−T0)), where T0 and T1 were the tail-flick latencies before and after the administration of morphine and T2 was the cut-off time (set at 10 s) in the tests to avoid injury to the tail. In the present study, the antinociceptive assay was performed 28 d after partial sciatic nerve-ligation. Each group consisted of 7–10 mice. Mechanical allodynia after sciatic nerve ligation was evaluated using the von Frey test (Fruhstorfer et al., 2001; Keizer et al., 2007; Pitcher et al., 1999).

RNA Preparation from the Tissue SamplesRNA was extracted from approximately 15 mg of frozen small intestine and brain using the TRI reagent (Life Technologies, U.S.A.). The resulting solution was diluted 50-fold using TE buffer, and the purity and concentration (µg/mL) of the RNA were calculated by measuring absorbance at 260 and 280 nm using a U-2800 spectrophotometer (Hitachi High Technologies, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantitative-PCRA high-capacity cDNA synthesis kit was used to synthesize cDNA from 1 µg of RNA. Tris-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (TE) buffer was used to dilute the cDNA 20-fold for the cDNA TE buffer solution. To each well of a 96-well PCR plate, 25 µL of iQ SYBR green supermix, 3 µL of forward primer of the target gene (5 pmol/µL), 3 µL of reverse primer (5 pmol/µL), 4 µL of cDNA TE buffer solution, and 15 µL of RNase-free water were added. The denaturation temperature was set at 95°C for 15 s, the annealing temperature was set at 56°C for 30 s, and the elongation temperature was set at 72°C for 30 s. The fluorescence intensity of the amplification process was monitored using the My iQ™ single color real-time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The mRNA expression levels were normalised using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Table 1).

Table 1. Primer Sequences for Mouse mRNA

| Target | Accession number | Forward primer (5′ to 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ to 3′) | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|

| UGT2B1 | HM_152811 | GGGAGACCTACAACATTAACCTGAGA | CCCAGAAGGTTCGAACGAG | 67 |

| CYP3A11 | NM_007818 | CGCCTCTCCTTGCTGTCACA | CTTTGCCTTCTGCCTCAAGT | 260 |

| CYP3A25 | NM_019792 | CAAGCACTTCCATTTCCCTC | CTTATTGGGCAGAGTTCTGTC | 98 |

| GAPDH | Hm_008084 | GGCAAATTCAACCGGCACAGT | AGATGGTGATGGGCTTCCC | 70 |

Nuclear extracts were prepared using the NE-PER nuclear extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. CER II reagent was added to 100 mg of liver tissue. The mixture was homogenized with 8 strokes at 1000 rpm at 4°C using a polytron homogenizer as a stirrer (2 cm3, HOM, AS ONE Cooperation, Osaka, Japan), followed by incubation on ice. The homogenate was then mixed with the CER II reagent and centrifuged for 5 min at 16000×g at 4°C. After removing the supernatant, the pellet was suspended in the NER reagent. The suspension was incubated and centrifuged for 10 min at 16000×g at 4°C, and the supernatant was used as the nuclear extract sample.

Statistical AnalysisThe numerical data are expressed as the mean±standard error (S.E.) or standard deviation (S.D.). The significance of the differences were examined by Student’s t-tests for pairs of values. The results with values of p<0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

A mouse neuropathic pain model was prepared and the mRNA expression level of UGT2B1 in the liver was measured on days 3, 7, and 28 after model preparation (Fig. 1). Increased expression of UGT2B in the liver was evident only on day 28, but not on days 3 and 7, suggesting that the increased expression of UGT2B in the liver occurred during the maintenance phase and not in the induction phase of neuropathic pain.

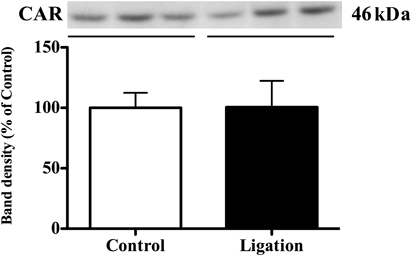

Since the expression of UGT2B has been shown to be regulated by the CAR nuclear receptor, CAR activity was analyzed based on the amount transported into the nucleus. On day 28, when a significant increase in the expression level of UGT2B was observed in the neuropathic pain group compared with the control group, there was no difference in the amount of CAR transported to nucleus in the liver between groups (Fig. 2) To confirm the absence of CAR activation, the mRNA expression level of CYP2B10, which is induced by CAR activation, was measured (Fig. 3). The mRNA expression level of CYP2B10 in the liver on day 28 in the neuropathic pain group was relatively higher than that in control mice, although no significant difference was found between groups.

Since it has recently been reported that another nuclear receptor, PXR, induces the expression of UGT2B, we also examined PXR activity (Fig. 4). The amount of PXR transported to the nucleus did not significantly differ between the neuropathic pain group and control group. Interestingly, however, the mRNA expression levels of CYP3A11 and CYP3A25 were nearly doubled via PXR in the neuropathic pain group (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION

Increased expression of UGT in the liver was not observed at 3 and 7 d following the preparation of mice models for neuropathic pain. However, expression did increase after 28 d (Fig. 1). In the area surrounding the nerve damage, chemokines (CCL2, CCL3) are released from inflammatory cytokines (interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha) and neurons of macrophages and mast cells.46,47) It has been reported that downstream of these inflammatory cytokines, nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) is activated, leading to the inhibition of PXR and RXR-alpha binding and lowered expression of cytochrome P450.48–50) Therefore, the decrease in UGT2B expression observed during the induction period appears to have resulted from such inflammatory cytokines. By contrast, the maintenance phase of neuropathic pain is a period during which astrocytes of the spinal cord are activated. An increase in the expression of UGT2B is likely to be associated with the activation of these astrocytes.

If this is the case, why is there an increase in the expression of UGT during the maintenance phase? It is currently known that the main molecules responsible for the control of UGT2B expression are the nuclear receptors CAR and PXR. In our study, we first conducted experiments that were focused on CAR. No change was found in the amount of intranuclear localization of CAR between the control group and the treatment group (Fig. 2). In addition, when the CYP2B10 mRNA expression, which is controlled by CAR, was quantitatively determined, no change was found between the two groups. These results suggest that CAR has no role in increasing the expression of liver UGT2B.

Next, we conducted experiments focusing on PXR. No changes in the amount of intranuclear localization of PXR were noted between the control group and the treatment group (Fig. 3). However, the expression levels of CYP3A11 and CYP3A25 mRNA, which are controlled by PXR, were found to have increased by about two-fold in the treatment group (Fig. 5). Based on these results, it is possible that the increase of UGT is independent of intranuclear localization of PXR, and may have been caused only by transcriptional activation. Histone modification by protein arginine methyltransferase 1 (PRMT1) has recently been reported to play an important role in the binding sequence of PXR (PXRE) during the transcriptional activation of the ligand-dependent CYP3A4 of PXR.51) It has also been reported that a decrease in the acetylation of histones near PXRE, which is located on the promoter of CYP3A2, leads to a decrease in the transcriptional activity of CYP3A2 in rats with chronic kidney disease.52) In addition, it has been reported that there is an enhancement in histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity at the time of neuropathic pain.53) A possible mechanism underlying the increased expression of UGT2B can be proposed based on these reports. Namely, since histone acetylation was enhanced in the promoter region of UGT2B in the liver and the ability to bind to the response sequence of PXR increased, it is thought that the expression of UGT was enhanced without an increase in the nuclear translocation of PXR.

By contrast, in the regulation of CYP3A11 expression, the possibility of the existence of an unknown pathway that does not require mediation by PXR and CAR cannot be denied. This is because it has been reported that CYP3A11 expression increases in PXR null mice,54,55) and that there is no change in the amount of CYP3A11 expression among CAR mice, PXR null/CAR null mice.56) However, at present, the mechanism of CYP3A11 expression control that is not mediated by PXR and CAR has not been elucidated. Therefore further studies are necessary to examine the authenticity of this mechanism.

Finally, the results of the present study did not demonstrate a relationship between the activation of astrocytes and increased expression of UGT2B in the periphery. In order to clarify aspects such as the relationship between the activation of astrocytes and enhanced activity of HAT, epigenetic analysis studies may be necessary in future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Yoshitaka Tozawa, Mr. Osamu Kosaka, Mr. Hiroyuki Yoshida, for their technical assistance. Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT)-Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities, 2014–2018, S1411019.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1) Kiguchi N, Maeda T, Kobayashi Y, Fukazawa Y, Kishioka S. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1alpha mediates the development of neuropathic pain following peripheral nerve injury through interleukin-1beta up-regulation. Pain, 149, 305–315 (2010).

- 2) Saika F, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Fukazawa Y, Kishioka S. CC-chemokine ligand 4/macrophage inflammatory protein-1beta participates in the induction of neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury. Eur. J. Pain, 16, 1271–1280 (2012).

- 3) Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Maeda T, Saika F, Kishioka S. CC-chemokine MIP-1alpha in the spinal cord contributes to nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain. Neurosci. Lett., 484, 17–21 (2010).

- 4) Zhao CM, Guo RX, Hu F, Meng JL, Mo LQ, Chen PX, Liao XX, Cui Y, Feng JQ. Spinal MCP-1 contributes to the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance in rats. Am. J. Med. Sci., 344, 473–479 (2012).

- 5) Hervera A, Leanez S, Negrete R, Motterlini R, Pol O. Carbon monoxide reduces neuropathic pain and spinal microglial activation by inhibiting nitric oxide synthesis in mice. PLoS ONE, 7, e43693 (2012).

- 6) Kim D, Kim MA, Cho IH, Kim MS, Lee S, Jo EK, Choi SY, Park K, Kim JS, Akira S, Na HS, Oh SB, Lee SJ. A critical role of toll-like receptor 2 in nerve injury-induced spinal cord glial cell activation and pain hypersensitivity. J. Biol. Chem., 282, 14975–14983 (2007).

- 7) Kuboyama K, Tsuda M, Tsutsui M, Toyohara Y, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Shimokawa H, Yanagihara N, Inoue K. Reduced spinal microglial activation and neuropathic pain after nerve injury in mice lacking all three nitric oxide synthases. Mol. Pain, 7, 50 (2011).

- 8) Narita M, Yoshida T, Nakajima M, Narita M, Miyatake M, Takagi T, Yajima Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence for spinal cord microglia in the development of a neuropathic pain-like state in mice. J. Neurochem., 97, 1337–1348 (2006).

- 9) Tsuda M, Masuda T, Kitano J, Shimoyama H, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Inoue K. IFN-gamma receptor signaling mediates spinal microglia activation driving neuropathic pain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 106, 8032–8037 (2009).

- 10) Beggs S, Trang T, Salter MW. P2X4R+ microglia drive neuropathic pain. Nat. Neurosci., 15, 1068–1073 (2012).

- 11) Biber K, Tsuda M, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Tsukamoto K, Toyomitsu E, Masuda T, Boddeke H, Inoue K. Neuronal CCL21 up-regulates microglia P2X4 expression and initiates neuropathic pain development. EMBO J., 30, 1864–1873 (2011).

- 12) Tsuda M, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, Mizokoshi A, Kohsaka S, Salter MW, Inoue K. P2X4 receptors induced in spinal microglia gate tactile allodynia after nerve injury. Nature, 424, 778–783 (2003).

- 13) Trang T, Beggs S, Wan X, Salter MW. P2X4-receptor-mediated synthesis and release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in microglia is dependent on calcium and p38-mitogen-activated protein kinase activation. J. Neurosci., 29, 3518–3528 (2009).

- 14) Yajima Y, Narita M, Usui A, Kaneko C, Miyatake M, Narita M, Yamaguchi T, Tamaki H, Wachi H, Seyama Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence for the involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the development of a neuropathic pain-like state in mice. J. Neurochem., 93, 584–594 (2005).

- 15) Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De Koninck Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature, 438, 1017–1021 (2005).

- 16) Masuda T, Tsuda M, Yoshinaga R, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Ozato K, Tamura T, Inoue K. IRF8 is a critical transcription factor for transforming microglia into a reactive phenotype. Cell Reports, 1, 334–340 (2012).

- 17) Deumens R, Jaken RJ, Knaepen L, van der Meulen I, Joosten EA. Inverse relation between intensity of GFAP expression in the substantia gelatinosa and degree of chronic mechanical allodynia. Neurosci. Lett., 452, 101–105 (2009).

- 18) Mika J, Osikowicz M, Rojewska E, Korostynski M, Wawrzczak-Bargiela A, Przewlocki R, Przewlocka B. Differential activation of spinal microglial and astroglial cells in a mouse model of peripheral neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 623, 65–72 (2009).

- 19) Miyoshi K, Obata K, Kondo T, Okamura H, Noguchi K. Interleukin-18-mediated microglia/astrocyte interaction in the spinal cord enhances neuropathic pain processing after nerve injury. J. Neurosci., 28, 12775–12787 (2008).

- 20) Romero-Sandoval A, Chai N, Nutile-McMenemy N, Deleo JA. A comparison of spinal Iba1 and GFAP expression in rodent models of acute and chronic pain. Brain Res., 1219, 116–126 (2008).

- 21) Kawasaki Y, Xu ZZ, Wang X, Park JY, Zhuang ZY, Tan PH, Gao YJ, Roy K, Corfas G, Lo EH, Ji RR. Distinct roles of matrix metalloproteases in the early- and late-phase development of neuropathic pain. Nat. Med., 14, 331–336 (2008).

- 22) Mika J, Zychowska M, Popiolek-Barczyk K, Rojewska E, Przewlocka B. Importance of glial activation in neuropathic pain. Eur. J. Pharmacol., 716, 106–119 (2013).

- 23) Shibata K, Sugawara T, Fujishita K, Shinozaki Y, Matsukawa T, Suzuki T, Koizumi S. The astrocyte-targeted therapy by Bushi for the neuropathic pain in mice. PLoS ONE, 6, e23510 (2011).

- 24) Tsuda M, Kohro Y, Yano T, Tsujikawa T, Kitano J, Tozaki-Saitoh H, Koyanagi S, Ohdo S, Ji RR, Salter MW, Inoue K. JAK-STAT3 pathway regulates spinal astrocyte proliferation and neuropathic pain maintenance in rats. Brain: A Journal of Neurology, 134, 1127–1139 (2011).

- 25) Vallejo R, Tilley DM, Vogel L, Benyamin R. The role of glia and the immune system in the development and maintenance of neuropathic pain. Pain Practice: The Official Journal of World Institute of Pain, 10, 167–184 (2010).

- 26) Cahill CM, Xue L, Grenier P, Magnussen C, Lecour S, Olmstead MC. Changes in morphine reward in a model of neuropathic pain. Behav. Pharmacol., 24, 207–213 (2013).

- 27) Matsuzawa-Yanagida K, Narita M, Nakajima M, Kuzumaki N, Niikura K, Nozaki H, Takagi T, Tamai E, Hareyama N, Terada M, Yamazaki M, Suzuki T. Usefulness of antidepressants for improving the neuropathic pain-like state and pain-induced anxiety through actions at different brain sites. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33, 1952–1965 (2008).

- 28) Odo M, Koh K, Takada T, Yamashita A, Narita M, Kuzumaki N, Ikegami D, Sakai H, Iseki M, Inada E, Narita M. Changes in circadian rhythm for mRNA expression of melatonin 1A and 1B receptors in the hypothalamus under a neuropathic pain-like state. Synapse, 68, 153–158 (2014).

- 29) Ochiai W, Kaneta M, Nagae M, Yuzuhara A, Li X, Suzuki H, Hanagata M, Kitaoka S, Suto W, Kusunoki Y, Kon R, Miyashita K, Masukawa D, Ikarashi N, Narita M, Suzuki T, Sugiyama K. Mice with neuropathic pain exhibit morphine tolerance due to a decrease in the morphine concentration in the brain. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci., 92, 298–304 (2016).

- 30) Buckley DB, Klaassen CD. Induction of mouse UDP-glucuronosyltransferase mRNA expression in liver and intestine by activators of aryl-hydrocarbon receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, pregnane X receptor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2. Drug Metab. Dispos., 37, 847–856 (2009).

- 31) Shelby MK, Klaassen CD. Induction of rat UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in liver and duodenum by microsomal enzyme inducers that activate various transcriptional pathways. Drug Metab. Dispos., 34, 1772–1778 (2006).

- 32) Tolson AH, Wang H. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes by xenobiotic receptors: PXR and CAR. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev., 62, 1238–1249 (2010).

- 33) Hernandez JP, Mota LC, Huang W, Moore DD, Baldwin WS. Sexually dimorphic regulation and induction of P450s by the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Toxicology, 256, 53–64 (2009).

- 34) Honkakoski P, Zelko I, Sueyoshi T, Negishi M. The nuclear orphan receptor CAR-retinoid X receptor heterodimer activates the phenobarbital-responsive enhancer module of the CYP2B gene. Mol. Cell. Biol., 18, 5652–5658 (1998).

- 35) Xie W, Barwick JL, Simon CM, Pierce AM, Safe S, Blumberg B, Guzelian PS, Evans RM. Reciprocal activation of xenobiotic response genes by nuclear receptors SXR/PXR and CAR. Genes Dev., 14, 3014–3023 (2000).

- 36) Guo GL, Lambert G, Negishi M, Ward JM, Brewer HB Jr, Kliewer SA, Gonzalez FJ, Sinal CJ. Complementary roles of farnesoid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor in protection against bile acid toxicity. J. Biol. Chem., 278, 45062–45071 (2003).

- 37) Kast HR, Goodwin B, Tarr PT, Jones SA, Anisfeld AM, Stoltz CM, Tontonoz P, Kliewer S, Willson TM, Edwards PA. Regulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (ABCC2) by the nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor, farnesoid X-activated receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 2908–2915 (2002).

- 38) Hartley DP, Dai X, He YD, Carlini EJ, Wang B, Huskey SE, Ulrich RG, Rushmore TH, Evers R, Evans DC. Activators of the rat pregnane X receptor differentially modulate hepatic and intestinal gene expression. Mol. Pharmacol., 65, 1159–1171 (2004).

- 39) Ratajewski M, Walczak-Drzewiecka A, Salkowska A, Dastych J. Aflatoxins upregulate CYP3A4 mRNA expression in a process that involves the PXR transcription factor. Toxicol. Lett., 205, 146–153 (2011).

- 40) Lehmann JM, McKee DD, Watson MA, Willson TM, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. The human orphan nuclear receptor PXR is activated by compounds that regulate CYP3A4 gene expression and cause drug interactions. J. Clin. Invest., 102, 1016–1023 (1998).

- 41) Bertilsson G, Heidrich J, Svensson K, Asman M, Jendeberg L, Sydow-Backman M, Ohlsson R, Postlind H, Blomquist P, Berkenstam A. Identification of a human nuclear receptor defines a new signaling pathway for CYP3A induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 95, 12208–12213 (1998).

- 42) Kliewer SA, Moore JT, Wade L, Staudinger JL, Watson MA, Jones SA, McKee DD, Oliver BB, Willson TM, Zetterstrom RH, Perlmann T, Lehmann JM. An orphan nuclear receptor activated by pregnanes defines a novel steroid signaling pathway. Cell, 92, 73–82 (1998).

- 43) Chen YH, Wang JP, Wang H, Sun MF, Wei LZ, Wei W, Xu DX. Lipopolysaccharide treatment downregulates the expression of the pregnane X receptor, cyp3a11 and mdr1a genes in mouse placenta. Toxicology, 211, 242–252 (2005).

- 44) Geick A, Eichelbaum M, Burk O. Nuclear receptor response elements mediate induction of intestinal MDR1 by rifampin. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 14581–14587 (2001).

- 45) Maglich JM, Stoltz CM, Goodwin B, Hawkins-Brown D, Moore JT, Kliewer SA. Nuclear pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor regulate overlapping but distinct sets of genes involved in xenobiotic detoxification. Mol. Pharmacol., 62, 638–646 (2002).

- 46) Moalem G, Tracey DJ. Immune and inflammatory mechanisms in neuropathic pain. Brain Res. Rev., 51, 240–264 (2006).

- 47) Scholz J, Woolf CJ. The neuropathic pain triad: neurons, immune cells and glia. Nat. Neurosci., 10, 1361–1368 (2007).

- 48) Gu X, Ke S, Liu D, Sheng T, Thomas PE, Rabson AB, Gallo MA, Xie W, Tian Y. Role of NF-kappaB in regulation of PXR-mediated gene expression: a mechanism for the suppression of cytochrome P-450 3A4 by proinflammatory agents. J. Biol. Chem., 281, 17882–17889 (2006).

- 49) Pascussi JM, Vilarem MJ. Inflammation and drug metabolism: NF-kappaB and the CAR and PXR xeno-receptors. Med. Sci. (Paris), 24, 301–305 (2008).

- 50) Zordoky BN, El-Kadi AO. Role of NF-kappaB in the regulation of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Curr. Drug Metab., 10, 164–178 (2009).

- 51) Xie Y, Ke S, Ouyang N, He J, Xie W, Bedford MT, Tian Y. Epigenetic regulation of transcriptional activity of pregnane X receptor by protein arginine methyltransferase 1. J. Biol. Chem., 284, 9199–9205 (2009).

- 52) Velenosi TJ, Feere DA, Sohi G, Hardy DB, Urquhart BL. Decreased nuclear receptor activity and epigenetic modulation associates with down-regulation of hepatic drug-metabolizing enzymes in chronic kidney disease. FASEB J., 28, 5388–5397 (2014).

- 53) Zhu X, Li Q, Chang R, Yang D, Song Z, Guo Q, Huang C. Curcumin alleviates neuropathic pain by inhibiting p300/CBP histone acetyltransferase activity-regulated expression of BDNF and cox-2 in a rat model. PLoS ONE, 9, e91303 (2014).

- 54) Schuetz EG, Strom S, Yasuda K, Lecureur V, Assem M, Brimer C, Lamba J, Kim RB, Ramachandran V, Komoroski BJ, Venkataramanan R, Cai H, Sinal CJ, Gonzalez FJ, Schuetz JD. Disrupted bile acid homeostasis reveals an unexpected interaction among nuclear hormone receptors, transporters, and cytochrome P450. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 39411–39418 (2001).

- 55) Staudinger JL, Goodwin B, Jones SA, Hawkins-Brown D, MacKenzie KI, LaTour A, Liu Y, Klaassen CD, Brown KK, Reinhard J, Willson TM, Koller BH, Kliewer SA. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 98, 3369–3374 (2001).

- 56) Scheer N, Ross J, Rode A, Zevnik B, Niehaves S, Faust N, Wolf CR. A novel panel of mouse models to evaluate the role of human pregnane X receptor and constitutive androstane receptor in drug response. J. Clin. Invest., 118, 3228–3239 (2008).