2021 Volume 44 Issue 8 Pages 1060-1066

2021 Volume 44 Issue 8 Pages 1060-1066

Optimization of medication therapy for the elderly is a matter of rapidly growing importance, which is addressed by pharmacists through comprehensive reviews. In this study, the impact of medication review by pharmacists on medication optimization and avoidance of adverse drug events (ADE) was investigated, as well as differences in the triggers for pharmaceutical intervention to allow for optimization of medication by patient age. Data for this study were collected from reports recorded between April 2013 and March 2019 for patients admitted to the Hiroshima University Hospital. In response to pharmacists’ proposals, prescriptions were modified in 18932 cases, comprising 17% of the total 111479 patients during hospitalization. The frequency of such intervention was higher in elderly patients aged ≥65 years than in those <65 years (20 vs. 14%, p < 0.01). The reasons for pharmacists’ intervention were primarily (67%) medication history or clinical symptoms in all age groups. Patient complaint was a minor reason in patients aged ≥75 years, accounting for only 2% of all interventions; laboratory results were a more typical reason, accounting for 24% of all interventions. These findings reveal the importance of pharmacists’ interventions for optimizing medication and preventing ADEs, particularly in elderly patients. Thus, pharmacists must evaluate the medications and conditions, including laboratory results, in the medical records of elderly patients more carefully than those of younger patients as elderly patients might be unable to communicate about subjective symptoms.

Medication-related harms account for 6.7–12.1% of hospital admissions, depending on the studies and definition used to identify the adverse drug events (ADE).1,2) Meanwhile, several studies have shown that half of medication-related harms are preventable.3–5) Therefore, to improve patient safety worldwide, assessing local ADE and medication errors, as well as the pharmacist’s role in addressing these, is essential. Pharmacist interventions, such as comprehensive medication reviews, extraction of information related to the medication from medical records, interviews with the patient, assessment of the prescribed medicines, and making prescription changes or modification after discussion with physicians, can contribute to the reduction of medication-related harms.6–9) Although additional, rigorously designed studies are required, several systematic reviews have provided evidence that pharmacists’ interventions through medication review are effective in reducing hospital readmissions.10–14)

In Japan, the “Guidelines for Medical Treatment and Its Safety in the Elderly” was published and disseminated in 2015 from the Japan Geriatrics Society. In 2016, pharmacists became eligible to receive a fee from Japan’s National Health Insurance System when they intervene an inappropriate prescription for patients on polypharmacy. Consequently, pharmacists have become more cautious when assessing elderly patients with multiple drugs therapy, to reduce the ADE caused by polypharmacy.15)

Meanwhile, the process of standardization and prevention of ADE has remained a significant challenge due to the significant variation in pharmacists’ intervention procedures across countries and facilities.16) The purpose of this study was, therefore, to evaluate the impact of medication review by pharmacists on medication optimization and avoidance of ADE in elderly patients, as well as the differences in triggers for pharmaceutical intervention to optimize medication by patient age.

Hiroshima University Hospital (HUH) is a university-affiliated institution with 746 beds that has been designated as a special functioning hospital by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan as it can provide advanced medical care, such as cancer care as well as emergency and critical care. Further, it can implement advanced medical technologies and conduct advanced medical care training for healthcare professionals.

In the HUH, all hospitalized patients have received medication review by pharmacists on weekdays since 2007. The associated procedure is as follows (Fig. 1): Step 1, Pharmacists obtain a series of medication history using at least two sources, such as a drug notebook, or medications brought to the hospital by the patient on the first day of admission. Step 2, Pharmacists record the medications brought by patients on the medication history in the electronic medical record. Step 3, Pharmacists identify and resolve medication discrepancies, unclear information, or changes within 24 h of admission. Step 4, Pharmacists stationed in all wards review medical records at least once daily on weekdays and visit patients, if necessary. Pharmacists should interview patients at least once a week and objectively evaluate medication-related issues. Pharmacists generally discuss how to improve patient-tailored pharmacotherapy plans with the physicians, nurses and patient. Pharmacists review the treatment regimen to determine whether patients can continue to receive medicines at home or in a long-stay hospital, following discharge or transfer to another hospital, respectively. Step 5, Provide coordinating information during transitions in care both within, and outside, of the organization; provide patient education on safe medication use; communicate with other providers.

The Japanese Society of Hospital Pharmacists (JSHP) created, and began operating, the PreAVOID reporting system in 1999 that allowed pharmacists across the country to register (1) cases of avoided aggravation of ADE and (2) cases of prevented ADE induction by pharmacist intervention. Subsequently, beginning in 2017, JSHP began to collect data on (3) cases of improved drug efficacy following pharmacist intervention in addition to cases of ADE avoidance. This system has facilitated the quantification of how effective pharmacist intervention is on improving medication safety and efficacy.17)

The term ‘avoidance of ADE aggravation’ refers to effects following pharmacist intervention during the early stage of medication use, based on patient’s complaints or laboratory results. Alternatively, ‘prevention of ADEs’ indicates that pharmacists identified potential ADEs based on the patients’ history, and medication history leading to their suggestion of alternative prescriptions. ‘Improved drug efficacy’ refers to a recommended change in prescription, by the pharmacist, if the required drug, or sufficient dose of that drug, is not prescribed. Other prescription inquiries regarding dispensing are not included in PreAVOID reports.

In the HUH, an intranet reporting system was installed in 2007 allowing the pharmacists to complete reports for each case. These reports include changes in prescription, date of prescription, drugs administered, specific recommendations by the pharmacist, and type of intervention as the result. From April 2013, two senior pharmacists, with more than 15 years of experience as a pharmacist, evaluated whether the medication changes resulting from a pharmacist’s suggestion improved the general condition of the patient based on improvements in abnormal laboratory results and/or side effect symptoms. The process of pharmacists reviewing medications and pharmaceutical intervention report collection in HUH is summarized in Fig. 1.

Analysis of PreAVOID ReportsPharmaceutical intervention for inpatients reported from April 2013 to March 2019 were extracted from the HUH’s electronic medical records. PreAVOID reports were classified by patient age (0–14, 15–39, 40–64, 65–74, >75 years), triggers (medication history, clinical symptoms, laboratory results, blood drug concentration, patient’s complaint)18) and outcome of pharmacists’ intervention (reduced drug dosage, drug discontinuation, increased drug dosage, switched drug, additional drug started, etc.),19) and subsequently analyzed. We also analyzed the type of pharmacists’ interventions and the type of medication based on patient age, using reports recorded from January 2017 to March 2019.

Statistical AnalysisAll analyses were performed using the SPSS 16.0 statistical package (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Differences in incidence between groups were analyzed by chi-square test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics ApprovalThis study was approved by the Hiroshima University Institutional Ethical Committee (No. E-1775-1).

During the study period, 111479 patients were admitted to HUH, 17.0% of whom (18932/111479) received pharmacists’ interventions that were clinically, or potentially clinically, relevant. When analyzed by age group, the percentage of patients receiving pharmacist intervention was 12.7% (874/6905) in 0–14-year-olds, 11.9% (1730/14529) in 15–39-year-olds, 14.8% (5151/34583) in 40–64-year-olds, 19.7% (6012/30552) in 65–74-year-olds and 20.7% (5165/24910) in those aged ≥75 years. Interventions by pharmacists were observed more frequently in elderly patients aged ≥65 years than in those aged <65 years (20% vs. 14%, p < 0.01; Fig. 2).

Next, we analyzed the triggers for pharmacist intervention, medications changed by the intervention, and laboratory tests that provided the rationale for intervention, by age group. The proportions of avoidance of ADE aggravation and prevention of ADEs tended to be higher among the elderly patients. In contrast, improvement of drug efficacy was more common in younger patients (Table 1).

| Reason | Total | Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 15–39 | 40–64 | 65–74 | ≥75 | ||

| Avoidance of ADE aggravation | 165 | 4 (0.7%) | 4 (0.6%) | 28 (1%) | 48 (1.7%) | 81 (3%) |

| Prevention of ADEs | 6521 | 327 (58.7%) | 407 (56.4%) | 1777 (64.8%) | 1988 (70.2%) | 2022 (75.1%) |

| Improvement of drug efficacy | 2906 | 226 (40.6%) | 314 (43.5%) | 939 (34.3%) | 799 (28.2%) | 628 (23.3%) |

| Number of reports | 9592 | 557 | 725 | 2744 | 2835 | 2731 |

Abbreviations: ADE, adverse drug event.

Figure 3A presents the reasons for the modification or change of medications by pharmacists’ intervention. Approximately two-thirds (67%) of the modifications, or changes, were related to patient’s medication history or clinical symptoms, while patient’s complaints accounted for only 5% of changes in medication and was the least common reason. We then stratified the patients by age and analyzed the frequency of the reason for changing prescription (Fig. 3B). Medication history or clinical symptoms were the predominate causes of medication change, with the highest frequency (approximately 60–70%) among all age groups. The proportion related to the patient’s complaint tended to decrease among elderly patients, accounting for only 2% of such modifications among those ≥75 years. In contrast, laboratory results tended to increase as the cause for medication changes in elderly patients: 7% for 0–14 years, 13% for 15–39 years, 15% for 40–64 years, 19% for 65–74 years, and 24% for the ≥75 years age (Fig. 3B).

(A) Ratio of reasons for medication modifications at prescription. (B) Variation in the proportion of different age groups according to each reason for medication modification.

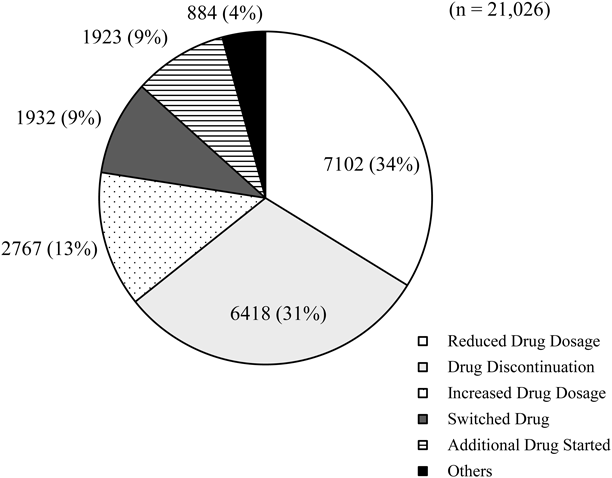

Results of the medication changes proposed by pharmacists are shown in Fig. 4. Reduced drug dosage (n = 7102; 34%), drug discontinuation (n = 6418; 31%), and increased drug dosage (n = 2767; 13%) were common outcomes for patients following pharmacist intervention (Fig. 4). Antibiotics, digestive organ agents, antineoplastics, and supportive care medications are commonly changed as a result of pharmacists’ interventions (Table 2). In addition, of the 21026 pharmaceutical intervention reports from 18932 patients, 14844 and 6182 interventions were related to oral medicines and injections, respectively.

| Drug class (multiple-choice allowed) | Number of reports | Age (years) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 15–39 | 40–64 | 65–74 | ≥75 | ||

| Antibiotics | 1950 | 142 | 211 | 613 | 554 | 430 |

| Digestive organ agents | 1147 | 27 | 61 | 264 | 354 | 441 |

| Antineoplastics/Supportive care | 1096 | 103 | 87 | 424 | 293 | 189 |

| Antipyretics and analgesics, anti-inflammatory agents | 775 | 58 | 62 | 188 | 202 | 265 |

| Anticoagulants | 409 | 9 | 16 | 98 | 120 | 166 |

| Anticholinergic agents | 380 | 13 | 14 | 100 | 115 | 138 |

| Antidiabetic agents | 351 | 4 | 8 | 88 | 138 | 113 |

| Electrolyte | 342 | 12 | 30 | 98 | 108 | 94 |

| Corticosteroids/Prednisolones | 341 | 24 | 37 | 96 | 108 | 76 |

| Antifungal | 317 | 74 | 48 | 80 | 83 | 32 |

| Sedatives/Anxiolytics | 306 | 9 | 22 | 97 | 63 | 115 |

| Antihypertensives | 294 | 7 | 12 | 63 | 97 | 115 |

| Blood substitutes | 266 | 4 | 11 | 60 | 84 | 107 |

| Antiplatelets | 258 | 3 | 2 | 28 | 101 | 124 |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 191 | 3 | 5 | 47 | 58 | 78 |

| Hyperlipidemia agents | 189 | 5 | 9 | 55 | 57 | 63 |

| Antivirals | 149 | 11 | 5 | 46 | 55 | 32 |

| Osteoporosis drugs | 141 | 1 | 10 | 31 | 56 | 43 |

| Narcotics | 127 | 2 | 3 | 37 | 52 | 33 |

| Diuretics | 124 | 4 | 7 | 26 | 48 | 39 |

| Gout preparations | 95 | 9 | 6 | 28 | 28 | 24 |

| Psychotropics | 82 | 3 | 11 | 30 | 17 | 21 |

| Thyroid hormone preparations | 81 | 0 | 3 | 27 | 27 | 24 |

| Vitamins/Minerals | 75 | 2 | 8 | 19 | 30 | 16 |

| Antiepileptics | 46 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 9 | 6 |

| Others | 398 | 30 | 49 | 143 | 104 | 72 |

Clinical parameters reported as the reasons for pharmacists’ intervention, as well as the related number of patients, are shown in Table 3. In descending order, serum creatinine (Scr), estimated glomerular filtration rate based on creatinine (eGFR), serum potassium, blood urea nitrogen, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio, and serum magnesium were the most common clinical parameters prompting pharmacist intervention.

| Number of reports (multiple-choice allowed) | |

|---|---|

| Serum creatinine (Scr) | 1845 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate based on creatinine (eGFR) | 424 |

| Potassium (K) | 368 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) | 241 |

| Prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PT-INR) | 157 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | 107 |

| Uric acid (UA) | 69 |

| Calcium (Ca) | 62 |

| Sodium (Na) | 56 |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 53 |

| Neutrophil count (NE) | 37 |

| Glucose | 37 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 34 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) | 32 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 32 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP) | 29 |

| Creatine kinase (CK) | 29 |

| D-dimer | 23 |

| Albumin | 22 |

| Platelet count (PLT) | 22 |

| Free thyroxine (FT4), Free triiodothyronine (FT3) | 22 |

| Hepatitis B virus-PCR (HBV-PCR) | 19 |

| White blood cell count (WBC) | 17 |

| Iron (Fe) | 13 |

| Inorganic phosphorus (IP) | 12 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) | 10 |

| Others | 90 |

Many countries are seeking strategies for pharmacists to work together with physicians to improve the optimal use of medication. In this study, we investigated the usefulness of pharmacists’ interventions on the optimization of medication therapy in HUH. Our results revealed that 17% of inpatients had their medication treatment optimized under pharmacist medication review. Pharmacist intervention was more frequent among the elderly (≥65 years) compared to the younger (<65 years) population (Fig. 2). Specifically, among patients aged 65 years and older, approximately 20% of prescribed medicines were modified or changed according to proposals by the pharmacist. Meanwhile, approximately 12% of the prescriptions were modified in patients aged 39 years or younger. This difference may be due to higher hepatic and renal functional reserves and fewer comorbidities in younger patients.

Furthermore, pharmacist interventions for the improvement of drug efficacy were observed more frequently in younger patients than in elderly patients, while the avoidance of ADE aggravation and prevention of ADEs were more frequent interventions in elderly patients (Table 1). Interventions typically associated with medication-related harms, poor adherence to medication therapy, and inappropriate drug selection were observed often in elderly patients (data not shown). These results support several reports that elderly patients have more ADEs and serious adverse events than younger patients due to increased drug sensitivity owing to age-related changes in metabolism as well as polypharmacy due to multiple comorbidities.20–23) Our results reinforce these reports and suggest that pharmacists should monitor the elderly patients more carefully than the younger.

The WHO launched a global patient safety challenge, Medication Without Harm, in 2017 to reduce medication-related harm by improving practices and reducing medication errors.16) It specifically encouraged countries to prioritize three areas, medication safety in high-risk situations, in polypharmacy, and in transitions of care to ensure medical safety. When patients begin new high-risk medicines, pharmacists should increase communication and engagement with patients and prioritize the monitoring of high-risk medicines over other medicines. However, it is difficult for pharmacists to know precisely which ADEs should be monitored, and how they should be managed, as there are many high-risk medications to be monitored. To address this challenge at HUH, we designed 706 templates that pharmacists can use to verify the prescription, and monitor potential ADEs, for each high-risk medication. The templates have been registered in the electronic medical records system and in 2010, the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Japan issued a notification encouraging collaboration between physicians and pharmacists. Additionally, considering that, at HUH, pharmacists can order laboratory tests for ADE monitoring if physicians have not done so, we have also created a procedure of medication review (Fig. 1) that allows pharmacists to perform streamlined and standardized review.

This study also revealed that the causes of pharmacist interventions differ between the elderly and younger patients (Fig. 3). For instance, in the elderly population patients’ complaint was rarely recorded as the cause for pharmacist intervention. Instead, following medication history or clinical symptoms, laboratory results were a more typical reason for pharmacist intervention in this population. Alternatively, in younger individuals, patient complaint was a more common cause for modifying medications, compared to elderly patients. Thus, elderly patients may not feel able to adequately voice their concerns about their symptoms to healthcare professionals owing to depression, decreased motivation, decreased vision and hearing, or reduced cognitive function.24,25) Additionally, the blood SCr and eGFR values were the most common laboratory results leading to changes in medication. It is speculated that medication review by pharmacists based on evaluation of the laboratory results is particularly effective to detect, and correct, inappropriate medications in elderly patients. We further classified prescription suggestions by pharmacists into six categories, the most frequent of which was reduced dosage or discontinuation of culprit drugs (Fig. 4). Although pharmacist interventions, for elderly patients specifically, can help to prevent polypharmacy, it is important to not only reduce the number of drugs but also optimize under-prescription in patients with a pre-existing condition. In the current study, pharmacists monitored under-prescription leading to the initiation of additional drugs or increased dosage of current medications. In fact, 22% of interventions led to increased drug dosage or additional drugs being prescribed (Fig. 4).

Our study has several limitations. First, this study summarized clinical data from a single university hospital that is capable of providing advanced medical care. Considering that ADEs are more likely to occur in university hospitals than in community hospitals,26) our findings may not be applicable to all hospitals of all categories. Second, physicians sometimes failed to accept the approach from pharmacists. Third, assessment of cost effectiveness and readmission after hospital discharge remain unclear, as investigation of these issues was beyond the study scope.

Our study provides evidence of the usefulness of pharmacist intervention for patient safety. It is particularly important for pharmacists to carefully evaluate pharmacotherapy for elderly patients based on objective laboratory results and information provided by caregivers as elderly patients might fail to accurately describe their own symptoms. In addition, pharmacists’ interventions, according to the actions and planning of the global patient safety challenge, “Medication Without Harm” of the WHO, are useful to establish a medication review for each hospital.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.