2023 Volume 46 Issue 9 Pages 1296-1303

2023 Volume 46 Issue 9 Pages 1296-1303

A shift towards obtaining emergency contraceptives without a prescription have been discussed in Japan. In response to this social background, we aimed at investigating the background of sexual intercourse, emergency contraceptive use, and knowledge of sexual and reproductive health education among women of reproductive age in Japan. In this study, we conducted a national wide cross-sectional questionnaire survey using a total of 4 web-based domains (background, sexual history, emergency contraceptives, and sexual and reproduction-related knowledge) composed of 50 questions. We obtained responses from a total of 4,631 participants of varying age groups (18–25, 26–35, and 36–45 years old) and 47 prefectures (84 to 118 from each prefecture). Among participant responses, 69.7% are sexually active, of which 49.0% had experiences of sexual intercourse with an unknown person. The responses from a total of 737 participants who have sexual intercourse, know of emergency contraceptives, and have experienced a situation that necessitated the use of emergency contraceptives, were analyzed. Of these participants, 46.4% (342/737) took emergency contraceptives, while 43.6% (321/737) participants did not take emergency contraceptives. Participants who have the knowledge for obtaining emergency contraceptives through the correct means were 52.6% (2438/4631). This study showed that approximately half of participants may not have correct knowledge of emergency contraceptives. In addition, approximately half of sexually active participants are facing unintended pregnancies due to a lack of sexual and reproductive awareness. Hence, comprehensive sex education is necessary to achieve social and regulatory changes centered on emergency contraceptives.

Emergency contraceptive pills (ECPs) are considered to be one of the women’s essential medications in their health care. The WHO announced the right to access emergency contraception and these knowledge for women.1) Cioffi et al. reported that the estimated utilization rate for ECPs was 10–40% in the European Union (EU).2) However, the authors’ concerns were about the differences in regulation levels among EC and the need for “massive information and awareness campaigns.”2) In the US, the use of ECPs is increasing from 0.8% in 1995 to 20.0% in 2015.3) These results suggest the importance of ECPs that are being used as a last chance to prevent intended pregnancy, which is a rising global women’s health concern. Importantly, the use of ECPs use and abortion are inseparable. In the US, women’s rights to abortions will be judged at the end of June 2022.4) In 2022, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US announced that the use of ECPs is not suitable for abortions based on scientific opinion.5,6) This statement answers the opinion of some antiabortion campaigners. Without a doubt, there are some negative attitudes toward the protection in postcoital behavior even if an adolescent uses ECPs.7) There are a lot of concerns arising even in some of the advanced countries that allow the use of ECPs.

In Japan, there is a history to approve oral contraceptives took more than 30 years according to the culture-based background.8,9) Difficulty in obtaining ECPs in Japan has been a concern for a long time.10) The non-prescription provision of ECPs was not approved by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) in 2016. This is due to some concerns of MHLW such as the safety and proper use of ECPs as well as the deficient literacy in the sexual and reproductive health education.11) The MHLW initiated public comments on December 27, 2022, that resumed discussions until January 31, 2023, in Japan.12,13) During the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, the number of consultations on reproductive coercion, sexual assault, and contraceptive failure is increasing in Japan.14,15)

The use of ECPs was reported to be increasing during the pandemic.16) Although some countries had negative attitudes towards the use of contraceptives by unmarried women due to cultural reasons,17) the interest in ECPs was increasing day by day in Japan. As mentioned previously, the need to know the proportion of sexually active women in their reproductive age, and to understand the extent of their knowledge in topics relating to “sexual and reproductive health education” are important issues to be explored. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the background of sexually active women, emergency contraceptive use, and the knowledge of sexual and reproductive health education among women of reproductive age in Japan.

This study was designed as a national-wide cross-sectional exploratory survey targeted towards the demographic of 18 to 45 years old women in Japan. This study was adopted by anonymized web-based data collection due to its nature, as this survey included questions about sexually personalized information and considers a web-familiar population of women between the ages of 18 to 45. We stratified the age (18–25, 26–35, and 36–45 years old) and living in each prefecture. Additionally, we planned that if the samples were deficient during study periods, we would supply them from neighboring prefectures due to similar environments.

This study was outsourced to the company which provides web-based data collection and recruitment through e-mail to candidates that considered both “entry criteria of the study” and “registered information.” We obtained informed consent from all participants using adequate method by web.

Questionnaire DevelopmentWe developed 4 domains with a total of 50 questions about 1) participants’ background, 2) sexual history, 3) emergency contraceptives, and 4) knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health education (Table 1). We modified the questionnaire after administering the questionnaire in person to eight clinical pharmacists to test the questionnaire’s comprehensiveness and clarity. In detail, we enhanced sentence fluency, chose words that are easily understood, and made sure to avoid any expressions that could cause discomfort to the participants in our revisions. The questionnaire was formatted as 1 question per web page. For logical data collection, we adopted adaptive questioning methods such as web page screen transitions that depend on each participant’s answer.

| Domain | No. of items | Items | Scaling | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Background | 22 | 1. Background (area, age, income, education, work, family structure) | Single, multiple-answer, free description |

| 2. Childbirth | ||||

| 3. Fertility treatment | ||||

| 2 | Sexual history | 6 | 1. Sexual history (sexually transmitted illness, sexual intercourse with an unknown person) | Single, multiple-answer, free description |

| 2. Experience for use of oral contraceptive | ||||

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | 10 | 1. Experience or experience for concern of emergency contraceptive use | Single, multiple-answer, free description |

| 2. About emergency contraceptive (about obtain, outcome) | ||||

| 3. Experience of visit in a hospital/clinic setting to prescribe emergency contraceptive | ||||

| 4. Barrier for obtain emergency contraceptive | ||||

| 4 | Knowledge related to sexual and reproductive health education | 12 | 1. About Sexual and reproductive health education related knowledges contents in Japan | Yes/No, free description, Semantic differential |

| 2. How to obtain the knowledge about sexual behavior. | scale (−5 – +5) | |||

| 3. How to obtain the knowledge about contraception | ||||

| 4. Knowledge for “emergency contraceptive,” “oral contraceptives,” “contraception,” “abortion” and “public service for women” | ||||

Questionnaire formatting was checked and fully reviewed by the investigator and system engineer. The questionnaire included an introduction, a description of the study’s purpose, and informed consent. Participants can start answering the questionnaire survey after filling out the informed consent. All participants are registered to outsourcing company; therefore, the duplicate answer can be excluded from the study. Additionally, we obtained fully anonymized data. Participants were motivated by trying to maximize their reward points as an incentive. A contrivance for these incentives was independent of investigators.

We reported our findings using the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys.18)

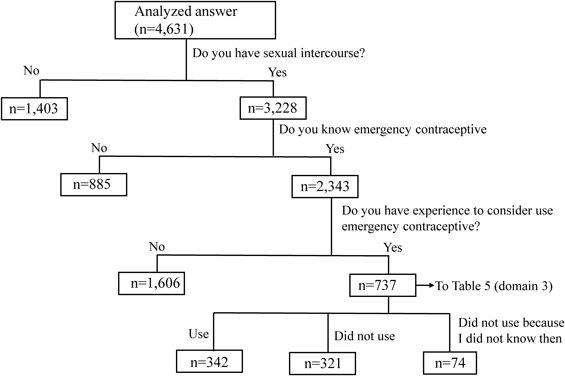

Study Procedure and DefinitionThe entry criteria included that the women’s age should be between 18 and 45 and that the participant should express informed consent to the study. The web survey was conducted between 22 November, 2022 and 5 December, 2022. A total of 5752 participants visited the website (Fig. 1). Among them, we excluded participants who did not match the entry criteria (n = 981). Participants who completed all questions were 4771, from which logically miss-matched answers for free word, yes/no, and single/multiple questions were excluded. Finally, 4631 participants were included in our study after excluding some responses belonging to the following criteria: 1) dishonest answer; 2) does not understand the question; and 3) logically miss-matched answer (n = 140). The number of participants collected from each prefecture was 84 to 118 (Fig. 2).

The definition of a denominator was different among the questions (Table 2). Briefly, participants’ background for Domain 1 was all participants (n = 4631), the calculation for “abortion” or “stillbirth” was considered for participants who have sexual intercourse (n = 3228), and calculations for “primipara” were for participants who have a child. Domains 2 and 3 depended on the question items such as from 171 to 4631 as a denominator.

| Domain | Measure | Denominator | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Background | Background (area, age, income, education, work, family structure), childbirth or experience for fertility treatment | All participants | 4631 |

| 1 | Background | Abortion or stillbirth | Have sexual intercourse | 3228 |

| 1 | Background | First childbirth age | Have child | 1487 |

| 2 | Sexual history | Sexual history, sexual transmitted illness, experience for oral contraceptive | All participants | 4631 |

| 2 | Sexual history | Age for first sexual intercourse, sexual intercourse with an unknown person | Have sexual intercourse | 3228 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | Experience for emergency contraceptive | All participants | 4631 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | Experience for the scene to consider use “emergency contraceptive” and the outcome | Participants with 1) “Have sexual intercourse” and 2) “Know emergency contraceptive” | 2343 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | Reason for the scene to consider use “emergency contraceptive” | Participants with 1) “Have sexual intercourse,” 2) “know emergency contraceptive” and 3) “experienced the scene to consider use emergency contraceptive” | 737 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | Way to obtain emergency contraceptive, and outcome of pregnancy | Participants with “Know emergency contraceptive” | 3104 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | Experience visiting hospital/clinic when you prescribed emergency contraceptive | Participants who have the experience prescribing emergency contraceptives at gynecology hospital/clinic | 412 |

| 3 | Emergency contraceptives | The reason why participant did not prescribe emergency contraceptive at hospital/clinic | Participants who have the experience to obtain emergency contraceptive from without hospital/clinic | 171 |

| 4 | Sexual and reproductive health education related knowledge | About sex-education and related knowledge | All participants | 4631 |

The primary endpoint of this descriptive exploratory survey was the measurement of Domain 3 that included proportions of “emergency contraceptive user,” and “experience to consider the use of emergency contraceptive, and the outcomes.” The secondary endpoint was Domain 4 measurements about sex education or sex-related knowledge descriptively.

All data are shown as simple tabulation. The proportion was calculated as a defined denominator in each question item (Table 2). The numerator is a measure in each question item (Table 2). The managed data was used, JMP 16® (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate, Consent for PublicationData were anonymized collected. We obtained informed consent form all participants using adequate method by web. The study protocol (“Questionnaire for Fact-finding survey to know about emergency contraceptives, pregnancy, and childbirth of women aged 18 to 45” as FIKA study) was approved at by the institutional review board of Showa University (9 November, 2022 approve, Approved No. 22-191-A).

In our study, a total of 4631 (18–25 years: 1586, 26–35 years: 1514, 36–45 years: 1531) including 2140 married women participated (Tables 2, 3). In this study, 32.1% (1487/4631) of participants have one or more children. The percentage of participants who went through fertilization treatments was 4.9% (225/4631). Additionally, 3.6% (168/4631) of participants have experienced living in a foreign country for over 3 months. A percentage of 63.7% of participants had a personal income that was under 2000 thousand JPY/year (2948/4631). Four percent of participants reached compulsory education as their final education level (184/4631). Unemployed participants were 25.6% (1185/4631) in the study.

| The number of participants | 4631 |

| Age group | |

| 18–25 | 1586 |

| 26–35 | 1514 |

| 36–45 | 1531 |

| Marriage history | 2140 |

| Experience for abortion | 410 |

| Experience for stillbirth | 366 |

| The number of participants for age of first birth | |

| 15–17 | 19 |

| 18–19 | 61 |

| Over 20 | 1407 |

| Experience for fertilization treatment | 225 |

| Experience for living without Japan over 3 months | 168 |

| Personal income (thousand JPY/year) | |

| 0–2000 | 2948 |

| 2000–4000 | 1215 |

| 4000–6000 | 340 |

| 6000–8000 | 72 |

| 8000–10000 | 24 |

| Over 10000 | 32 |

| Education level | |

| Compulsory education | 184 |

| Working style | |

| Student/day-time worker | 2272 |

| Daytime and night-time shift worker | 1112 |

| Night-time worker | 62 |

| Unemployed | 1185 |

A total of 69.7% (3228/4631) of participants have sexual intercourse (Table 2, 3). Among these participants, those who experienced abortion and stillbirth were 12.7% (410/3228) and 11.3% (366/3228), respectively.

Background for Sex History in the Study Participants (Domain 2)Participants who experienced sexually transmitted infections were 8.7% (403/4631) (Tables 2, 4). Oral contraceptives were used for regulating the menstrual cycle and for contraception in 9.4% (434/4631) and 5.2% (240/4631), respectively. The ages at which participants were sexually active at 10–12 and 13–15 years were 0.5% (16/3228) and 9.2% (298/3228), respectively (Tables 2, 4). Sexual intercourse with an unknown person was experienced by 49.0% (1583/3228) of participants.

| Sexual intercourse | |

| With | 3228 |

| Without | 1403 |

| Sexual intercourse with an unknown person | |

| Once | 404 |

| 2–5 times | 768 |

| 6–9 times | 163 |

| Over 10 times | 248 |

| Age for first sex intercourse | |

| 10–12 | 16 |

| 13–15 | 298 |

| 16–19 | 1591 |

| Over 20 | 1323 |

| Experience for sexually transmitted illnesses | 403 |

| Oral contraceptive user for menstrual irregularity | 434 |

| Oral contraceptive user for contraception | 240 |

Domain 3 involved obtaining information concerning emergency contraceptive. A total of 737 participants: 1) who have sexual intercourse, 2) who know emergency contraceptives, and 3) who have experienced a situation that necessitated the use of emergency contraceptives, were analyzed for the reasons and outcomes (Fig. 3, Tables 2, 5). Among these participants, 46.4% (342/737) took emergency contraceptives; however; 43.6% (321/737) participants did not take emergency contraceptives. Additionally, 10.0% (74/737) were not aware of the presence of emergency contraceptives when faced with a situation that necessitated their use (Fig. 3). Among the 737 participants, failure of using protection was the most frequent answer for the reason behind being placed in a situation necessitating the use of emergency contraceptives 37.9% (279/737) (Table 5). On the other hand, 11.4% (84/737) of participants were sexually assaulted which was attributed as their reason. A lack of knowledge was also observed by the partner, and the person, or both among 26.1% (192/737), 6.9% (51/737), and 27.3% (201/737), respectively.

| Lack of knowledge for pregnant risk by partner | 192 |

| Lack of knowledge for pregnant by myself | 51 |

| Lack of knowledge for pregnant both partner and myself | 201 |

| Failure protection | 279 |

| Sexual assault | 84 |

| Forgot to take oral contraceptive | 29 |

| Others | 17 |

Permit multiple answers.

We analyzed the way of obtaining emergency contraceptives in 3104 participants who were aware of “emergency contraceptives” (Tables 2, 6). A total of 19.8% (615/3104) of participants experience obtaining emergency contraceptives. Most of the participants, 82.8% (509/615), obtained them either at the hospital or clinics. On the other hand, 15.3% (94/615) of participants considered obtaining them through inadequate means such as “friends,” “website,” or “partner.” Some participants obtained them from the office or bought them from a foreign country’s pharmacy.

| Have not ever obtain | 2489 |

| Prescribed by Obstetrics | 412 |

| Prescribed by without Obstetrics | 32 |

| Telemedicine | 65 |

| Bought from website | 30 |

| Obtained from friend | 16 |

| Bought from friend | 6 |

| Obtained from partner | 36 |

| Bought from partner | 6 |

| Obtained at office | 11 |

| Others (bought at foreign country) | 1 |

Four hundred and twelve participants who were prescribed emergency contraceptives by the gynecologist in a hospital or clinic, 16.0% (66/412) faced some discomfort in terms of privacy during the interview or examination (Table 2). The reason behind a total of 171 participants not visiting a hospital or clinic was due to financial problems, which accounted for 18.1% (31/171). Additionally, 7.6% (13/171) of participants did not want to explain their situation to the physician and 7.1% (12/171) were advised by their friends or partners (Table 2).

Sexual and Reproductive Health Education-Related KnowledgeUsing the semantic differential 11-scale for the attitudes among participants, we asked whether sexual and reproductive health education during school education felt enough or lacking (Fig. 4). Among participants, 14.5% (671/4631) answered “quite lacking” (Table 2). On the other hand, 2.3% (104/4631) answered “enough.” Additionally, the majority of participants, 28.4% (1314/4631), answered that they obtained their sexual education involving, specifically information on sexual intercourse, from their education at school. While the remaining participants were 21.6% (1000/4631) and 16.9% (782/4631). answered that they received their education from websites and friends, respectively. Concerning contraceptives, 38.2% (1769/4631) the majority, received their sexual and reproductive health education at school. On the other hand, 21.3% (986/4631) and 16.7% (772/4631) obtained their information from websites or did not learn about contraceptives, respectively.

Regarding knowledge about sexual and reproductive health education, 11.4% (528/4631) answered correctly about the adequate timing for emergency contraceptives. Among participants, 32.0% (1482/4631) thought withdrawal was an adequate contraception method. Additionally, 52.6% (2438/4631) answered correctly on the way of obtaining emergency contraceptives. A total of 38.0% (1759/4631) believed that sexual and reproductive health education needs to start from elementary school.

In this study, we described the knowledge and experiences of participants on “emergency contraceptives,” “sexual history,” and “knowledge for sexual and reproductive health” divided into 4 domains in the study.

Previous reports emphasize different opportunities for sexual and reproductive health education as well as attitudes among varying ages and prefectures (urban or rural).19) Hence, we also stratified the prefecture and age. In the study, we observed that 12.7 and 11.3% of participants experienced abortion and stillbirth, respectively in Domain 1 (Tables 2, 3). The abortions and stillbirths reported approximated 140 and 17 thousand, respectively in 2020.20,21) These results are difficult to compare directly to the study because our data is based on a recall-typed questionnaire survey with different denominators (women who are active sexually). Of course, participants may have misunderstood stillbirth as including chemical abortion or abortion within 12 weeks. In any case, although regular use is never permitted, that could be prevented with correct contraceptive instructions and ECP use for women who have experienced abortions or stillbirths. A total of 49% experienced sexual intercourse with an unknown person in Domain 2 (Tables 2, 4). Additionally, sexually transmitted infections were observed among 8.7% (Table 4). Chlamydia and syphilis have been recently spreading.22,23) This is especially the case in women, whereby the number of reported syphilis cases increased from 124 in 2010 to 3658 in 2022. Additionally, the majority of women were between the ages of 20 to 29 years.23) This goes to show the importance of having the right knowledge and awareness on contraceptives, in addition to having the right to education.

In the US, unintended pregnancy reported cases were 49%.24) Additionally, the cost burden reached 5 billion US$ in 2002.25) The cost burden caused by unintended pregnancy estimates to be approximately 1.5 billion US$ in Japan.26) Nevertheless, unintended pregnancy may lead not only to financial issues but may also cause a burden on women’s health. Half of our study participants are faced with the avoidable risk of unintended pregnancies. Among participants, 737 had to consider the use of emergency contraceptives; 43.6% did not use, and 10.0% did not know of the existence of emergency contraceptives in Domain 3 (Table 2, Fig. 3). This is a considerable concern as it highlights the lack of knowledge and awareness on sexual and reproductive health education including, but not limited to: “how to obtain emergency contraceptive” and “how to obtain advised for public service” (Tables 2, 5, 6).

Our study showed that 14.5% of participants felt that their knowledge of sexual and reproductive health is “quite lacking” in Domain 4. In June 2021, the Nippon foundation conducted a web-based questionnaire survey for participants aged 17 to 19 years old (n = 1000). The survey showed that 29.7% did not have enough knowledge about sexual and reproductive health.27) Interestingly, our study showed that 38% of participants would like to introduce curriculums that tackled sexual intercourse from an early age (Domain 4). Additionally, the majority of the responses were that sexual and reproductive health education must start from elementary school as compared to junior high school, high school, and university.

Limitation for the StudyThis study has some limitations, one of which could have been participant bias. This might have been the case because our participants were motivated to try to maximize their reward points as an incentive. On the other hand, mobile devices are used by nearly 98% of the Japanese population.28) Especially in women in their 20 and 40s, over 90% were using the internet. We understand the bias, but most of the targeted population had the chance to try to join our study. Another limitation could be the population sampling method. The allocation of 99 participants per prefecture aimed to provide representative samples for each specific prefecture rather than for the entire country of Japan. However, it is worth mentioning that urban areas like Tokyo, Osaka, and Aichi have larger populations, resulting in a lower chance of participation in our study compared to rural prefectures. This discrepancy between urban and rural areas may influence the weight of 1 participants' result. Furthermore, there were two primary factors contributing to the discrepancy between the intended allocation of 99 samples per prefecture and the actual number of samples analyzed. Firstly, certain prefectures experienced a shortage of available samples. In accordance with the established protocol, samples from neighboring prefectures were provided to compensate for this shortfall. Secondly, an oversampling occurred due to the timing constraints associated with closing the questionnaire website. The precise control of this aspect proved challenging, primarily due to the aforementioned consideration regarding the sample shortage in certain prefectures. Additionally, it is important to consider that the study design is subject to potential limitations arising from participants potentially providing inaccurate information, which could potentially impact the results.

In this study, the results showed that approximately half of the women participants are facing unintended pregnancies due to their lack of sexual and reproductive knowledge, despite being sexually active. For this reason, comprehensive sex education centered on emergency contraceptives is necessary for preparing these women for social and regulatory changes.

This study is supported by a Grant from the OTC Self-Medication Promotion Foundation (58-3-2 and 36-3-1).

All authors meet the ICMJE recommendations. Especially, KM contributed to the study conception and drafted the manuscript. HH and KR were responsible for ethics handling. KM collected raw data. All authors built the questionnaire form. EM, HI, HT, HM, NH, and TS interpreted the results clinically. NS finally approved this study. All authors took part in the discussions during manuscript preparation. All authors have agreed to publish this manuscript.

KM received honorarium fees for presentations from Nippon-Kayaku, Abbvie, and Eisai. KM received a travel fee from Abbvie to join the meeting held by Abbvie. Department of Hospital Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, Showa University received funding from Ono with a contract research project according to the collaborative research agreement. As a potential conflict of interest, Hospital Pharmaceutics received a research grant from Daiichi Sankyo, Mochida, Shionogi, Ono, Taiho, and Nippon-Kayaku. Other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

This article contains supplementary materials.