2024 Volume 47 Issue 4 Pages 750-757

2024 Volume 47 Issue 4 Pages 750-757

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) is a drug efflux transporter expressed on the epithelial cells of the small intestine and on the lateral membrane of the bile duct in the liver; and is involved in the efflux of substrate drugs into the gastrointestinal lumen and secretion into bile. Recently, the area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) of rosuvastatin (ROS), a BCRP substrate drug, has been reported to be increased by BCRP inhibitors, and BCRP-mediated drug–drug interaction (DDI) has attracted attention. In this study, we performed a ROS uptake study using human colon cancer-derived Caco-2 cells and confirmed that BCRP inhibitors significantly increased the intracellular accumulation of ROS. The correlation between the cell to medium (C/M) ratio of ROS obtained by the in vitro study and the absorption rate constant (ka) ratio obtained by clinical analysis was examined, and a significant positive correlation was observed. Therefore, it is suggested that the in vitro study using Caco-2 cells could be used to quantitatively estimate BCRP-mediated DDI with ROS in the gastrointestinal tract.

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2), a member of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter family, is expressed on the epithelial cells of the small intestine and the bile duct lining of the liver as a drug efflux transporter. BCRP is involved in the efflux of substrate drugs into the gastrointestinal lumen and their secretion into bile.1) Rosuvastatin (ROS), rivaroxaban, salazosulfapyridine, and other substrate drugs are transported via BCRP,2–4) and inhibition of BCRP function in the gastrointestinal tract may lead to increased gastrointestinal absorption of these substrates. In fact, the area under the plasma concentration–time curve (AUC) of ROS has been reported to be increased by BCRP inhibitors such as febuxostat (FEB) and roxadustat (ROX),5,6) and BCRP-mediated drug–drug interaction (DDI) in the gastrointestinal tract has attracted attention.

ROS is a 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitor and is approved as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia, a lifestyle-related disease.7) After ROS is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract, a portion of it is excreted through the BCRP into the gastrointestinal lumen.8) The absorbed ROS is taken up by the liver mainly via the organic anion transporters (OATP1B1/OATP1B3),9) and excreted into bile via BCRP and multidrug resistance related protein 2 (MRP2).8,10) Therefore, BCRP inhibitors may reduce the efflux of ROS into the gastrointestinal lumen and its secretion into bile, thereby increasing the systemic exposure of ROS. Although increased systemic exposure of ROS may enhance the risk of developing rhabdomyolysis, a serious side effect, there is currently limited information on drugs that cause BCRP-mediated DDI with ROS in clinical study.

In this study, we performed ROS uptake study using human colon cancer-derived Caco-2 cells to investigate whether drugs that have been reported to cause DDI with ROS in clinical study increase intracellular accumulation of ROS in vitro.5,6,11–15) In addition, in order to examine whether BCRP-mediated DDI in the gastrointestinal tract can be estimated by in vitro study using Caco-2 cells, we analyzed DDI between ROS and BCRP inhibitors in clinical study. Furthermore, we evaluated whether there is a correlation between pharmacokinetic (PK) parameters obtained by clinical analysis and cell to medium (C/M) ratio obtained by in vitro study.

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), and tolvaptan (TOL) were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). Fetal bovine serum (FBS, Biosera, Nuaille, France), MEM-non-essential amino acids (MEM-NEAA), 0.25% trypsin–ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and penicillin–streptomycin (Pen-Strep) were purchased from Gibco (MA, U.S.A.). 24-well cell culture plates were obtained from Corning (NY, U.S.A.). FEB and ROS were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Capmatinib (CAP), fostamatinib (FOS), osimertinib (OSI), and rucaparib (RUC) were purchased from AdooQ Bioscience (CA, U.S.A.). ROX was purchased from MedChemExpress (NJ, U.S.A.). All other reagents and solvents were of commercial grade.

Cell CultureCaco-2 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, VA, U.S.A.), and passages 51–55 were used. DMEM containing 10% FBS, 5% MEM-NEAA and 1% Pen-Strep was used to culture Caco-2 cells and the medium was stored at 4 °C. Cells were cultured under humidified conditions at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Caco-2 cells were passaged as follows. After Caco-2 cells reached 80% confluence in a 10 cm dish, the culture medium was removed and washed with prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2, 37 °C). Then, 0.25% trypsin–EDTA was added to the cells and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C in 5% CO2 humidified conditions. After confirming that they were detached, the cells were suspended in new culture medium and centrifuged at 195 × g for 3 min at room temperature and transferred to a 10 cm dish.

Caco-2 cells used in the experiment were seeded in 24-well cell culture plates according to the following procedure. After Caco-2 cells reached 80% confluence in a 10 cm dish, the cell suspension was done according to the previously described method and prepared to a cell density of 2.0 × 105 cells/well. To each well of the cell culture plate 500 µL of the cell suspension was added, and the plates were incubated under humidified conditions of 37 °C and 5% CO2.

ROS Uptake StudyCaco-2 cells seeded in 24-well plates were cultured for 14 d and medium was replaced every 2–3 d. After pre-incubation for 10 min at 37 °C under static conditions, cells were washed twice with uptake buffer composed of Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS), 10 mM 2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (MES) and 4 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.4). Test reagents were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the final concentrations were made in uptake buffer (HBSS-MES) to be 20 µM ROS, 20 µM ROS (control) + 0.05 µM Ko143 (positive control) and 20 µM ROS + 125 µM each BCRP inhibitor (CAP, FEB, FOS, OSI, ROX, RUC and TOL).5,6,11–15) The final DMSO concentration was 1%. The concentration of each BCRP inhibitor in the gastrointestinal tract, calculated as the maximum dose in humans (mg)/250 mL H2O, was estimated to be 134–4300 µM. Considering solubility in DMSO, the inhibitor concentration to be added in the in vitro study was set at 125 µM. Since this is higher than the IC50 of each BCRP inhibitor (0.05–8.32 µM),5,12,13,15–18) BCRP was considered to be completely inhibited under these conditions.

The uptake study was initiated by adding 300 µL of the test reagents in uptake buffer to each well. After 30 min of incubation, the solutions were removed and the cells were washed three times with HBSS-MES at 4 °C to complete the uptake study. The cells were incubated with 400 µL/well of 1 M NaOH for 30 min at 37 °C, neutralized with 80 µL/well of 5 M HCl, and cells were collected. The protein content was determined colorimetrically using the DC™ Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.), based on the absorbance measurement at 700 nm (reference wavelength: 0 nm) with a microplate reader, Sunrise™ Rainbow (Tecan, Kanagawa, Japan). The ROS concentration measured by LC tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) was normalized by protein content, and C/M ratio was calculated using equation (1).

| (1) |

LC-MS/MS was performed using the DGU-20A degassing unit, LC-20ADXR pump, SIL-20AC autosampler, CBM-20A system controller and CTO-20A column oven. LCMS-8040 (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) was used in combination with LabSolutions LCMS software. The column was a CAPCELL PAK Type MG III-H (C18, 3 µm 2.0 mm ID × 100 mm, Osaka Soda, Osaka, Japan). The mobile phase consisted of 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q for A and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile for B at a ratio of 3 : 7. The flow rate was 0.20 mL/min, and the column oven was set at 40 °C. Chlorpropamide (CHL) was used as an internal standard. CHL has been used as internal standard for various test drugs in several previous studies.19) Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was conducted at m/z 481.90 > 258.00 for ROS and at m/z 274.90 > 190.05 for CHL. Collision energy was set to –37 V for ROS and 24 V for CHL. The coeffients of determination of all calibration curves were >0.999. The lower limit of quantification for Rosuvastatin was 0.3 nM.

For the sample preparation, 100 µL of the collected cell lysate was mixed with 100 µL of 200 nM CHL. To this mixture, 400 µL of ethyl acetate was added and vortexed, and 300 µL of the supernatant was collected. This process was repeated once and the ethyl acetate was evaporated (40 °C, 30 min). After volatilization, 200 µL of mobile phase was added to the residue and vortexed. The total volume was applied to MultiScreen® Solvent Filter Plates 0.45 µm Low-Binding Hydrophilic Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and centrifuged at 700 × g for 3 min at 4 °C. Filtered samples were collected in a 96-well microplate (Asone, Osaka, Japan) and injected (10 µL) into a vial for LC-MS/MS.

Calculation of PK Parameters of Clinically Reported CasesDDI between ROS and each BCRP inhibitor (CAP, FEB, FOS, OSI, ROX, RUC and TOL) in clinical study was simulated using WinNolin software (version 8.1, Pharsight Corporation) based on the linear two-compartment model, as shown in equation (2), and PK parameters (ka: absorption rate constant; ke1: elimination rate constant during distribution phase; ke2: elimination rate constant during elimination phase; A and B: concentration unit coefficients) were calculated. The plasma ROS concentration was denoted as C (ng/mL), time as t (h). AUC values were taken from the relevant literature.5,6,11–15) Plasma ROS concentrations were calculated from relevant literature using WebPlotDigitizer (version 4.3) (reliability was 0.99 and accuracy was 0.93).20,21)

| (2) |

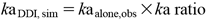

Based on the above conclusion, we calculated the simulation values (kaDDI,sim) of kaDDI (Table 1) as shown in equation (3) using the C/M ratio from the uptake studies of Caco-2 cells.

| (3) |

Then using the kaDDI,sim we calculated the AUCDDI,sim according to the following equation (4). In this equation, we used the PK parameters (A, B, ke1, ke2) in the absence of BCRP inhibitors.

| (4) |

| ka (h−1) | ke1 (h−1) | ke2 (h−1) | AUC (ng·h/mL) | A | B | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone*1 | DDI*2 | Ratio*3 | Alone | DDI | Ratio | Alone | DDI | Ratio | Alone | DDI | Ratio | Alone | DDI | Alone | DDI | |

| RUC | 2.19 | 0.93 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 1.05 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 192 | 276 | 1.44 | 23 | 40 | 3.8 | 4.2 |

| TOL | 0.33 | 0.36 | 1.09 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.07 | — | — | — | 19 | 30 | 1.57 | 16 | 36 | 0.4 | 2.7 |

| FEB | 0.36 | 0.39 | 1.08 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 1.39 | 43 | 83 | 1.94 | 56 | 88 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| FOS | 0.34 | 0.36 | 1.06 | 0.29 | 0.30 | 1.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.75 | 94 | 183 | 1.96 | 154 | 272 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| ROX | 0.35 | 0.44 | 1.25 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.94 | 68 | 196 | 2.90 | 97 | 95 | 1.4 | 2.7 |

| CAP | 0.56 | 0.68 | 1.20 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 1.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 1.21 | 78 | 159 | 2.03 | 59 | 95 | 1.5 | 2.7 |

| OSI | 0.56 | 0.91 | 1.62 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.86 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 131 | 184 | 1.41 | 33 | 34 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

DDI between ROS and each BCRP inhibitor (RUC, TOL, FEB, FOS, ROX, CAP and OSI) in clinical study was analyzed, and pharmacokinetic parameters (ka: absorption rate constant; ke1: elimination rate constant during distribution phase; ke2: elimination rate constant during elimination phase; A and B: concentration unit coefficients) were calculated. AUC values were taken from the relevant literature.5,6,11–15) Alone: ROS alone; DDI: ROS + BCRP inhibitor; ratio: DDI/alone. *1: kaalone,obs: observed ka value of ROS alone in clinical study; *2: kaDDI,obs: observed ka value of ROS during DDI with BCRP inhibitors in clinical study; *3: observed individual ka ratio.

All experimental data on ROS uptake study were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) (n = 3–4). Statistical analyses were performed using Pharmaco Basic software (Scientist Press Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Dunnett’s test and Pearson’s correlation test were used as significance tests. The significance level for each test was set at 5 or 1%, and a significance probability of p < 0.05 or p < 0.01 was considered as a significant difference.

The intracellular accumulation of ROS was significantly increased when ROS was administered in combination with all BCRP inhibitors except RUC, compared to ROS alone (Fig. 1). The effect of BCRP inhibitors on the accumulation of ROS in Caco-2 cells was different among BCRP inhibitors, with a minimum 1.19-fold increase by RUC and a maximum 3.08-fold increase by OSI.

By using 20 µM ROS for the uptake study in Caco-2 cells, we evaluated the intracellular accumulation of ROS in the presence of each 125 µM BCRP inhibitor (CAP, FEB, FOS, OSI, ROX, RUC and TOL). Ko143 (0.05 µM) was used as a positive control. Mean ± S.D. (n = 3–4), n refers to replicates within an experiment. Dunnett’s test (vs. Control), ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05, NS: Not significant.

In terms of DDI between ROS and BCRP inhibitors in the clinical analysis, ka was increased by all BCRP inhibitors except RUC compared to ROS alone, with a maximum 1.62-fold increase by OSI (Fig. 2, Table 1). In addition, ke1 was decreased by 0.86 to 0.88-fold in combination with several BCRP inhibitors (OSI and ROX), and ke2 was decreased by a minimum of 0.78-fold by RUC. Furthermore, AUC of ROS was increased by all BCRP inhibitors, with a maximum 2.90-fold increase by ROX (Table 1).

The correlation between the C/M ratio of ROS obtained from in vitro study and the ka, ke1, ke2, and AUC ratios of ROS obtained from clinical analysis were examined. There was a significant positive correlation between C/M ratio and ka ratio (Correlation coefficient of determination (R) = 0.939, p = 0.0017), which almost passed through the origin as shown in equation (5) (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, no significant correlation was observed between C/M ratio − ke1, ke2 and AUC ratio (Figs. 3B–D).

| (5) |

| (6) |

The correlation between the C/M ratio of ROS obtained by the in vitro study and the ka ratio (A), ke1 ratio (B), ke2 ratio (C) and AUC ratio (D) of ROS obtained by clinical study was evaluated. The regression line of each graph was indicated by a dashed line, and its Correlation coefficient of determination was shown by R. ka: absorption rate constant; ke1: elimination rate constant during distribution phase; ke2: elimination rate constant during elimination phase; ratio: DDI/alone.

The correlation between the AUCDDI,obs obtained from past literature and AUCDDI,sim obtained from simulation analysis using equation (4) was examined. A significant positive linearity between AUCDDI,obs and AUCDDI,sim was observed (R = 0.896, p = 0.0064) (Fig. 4A).

(A) The correlation between the observed AUCDDI (AUCDDI,obs, Table 1) quoted from the literature and the simulated AUCDDI (AUCDDI,sim, Table 2) obtained by equations (4) and (6). (B) The correlation between AUCDDI,obs and AUCDDI,expected obtained by equation (8). Correlation coefficient of determination was shown by R. Dashed line indicates a 1 : 1 line.

It has been reported that Caco-2 cells express BCRP, which is involved in the efflux of ROS.22) It has been confirmed that the Caco-2 cells used in this study express BCRP, although their mRNA expression level is different from that of human small intestinal epithelial cells.23) Therefore, we assumed that BCRP is functional in the Caco-2 cells used in this study.

For the in vitro study, the intracellular accumulation of ROS was significantly increased or tended to be increased in the presence of all BCRP inhibitors compared to ROS alone (Fig. 1). Since Ko143 is a selective BCRP inhibitor,24) the significant increase in intracellular accumulation of ROS observed in this study could be attributed to BCRP inhibition. In the case of OSI, the C/M ratio was greater than that of other inhibitors, including Ko143 (Fig. 1). The reason for this is not clear, but OSI might inhibit BCRP by a mechanism that is different from other inhibitors and may involve changes in BCRP function or structure.

The BCRP inhibitors except RUC used in the in vitro study increased the ka values of ROS from 1.06 to 1.62-fold in the clinical studies (Table 1). The AUC of ROS was also increased from 1.41 to 2.90-fold by the combination of all BCRP inhibitors (Table 1). These results may be attributed to enhanced gastrointestinal absorption due to inhibition of ROS efflux into the gastrointestinal tract lumen. ka values obtained under ROS-alone conditions in clinical trials using RUC as a BCRP inhibitor were 4 to 6 times higher than ka obtained in other clinical trials (Table 1). These studies were clinical pharmacology studies for DDI, and the dosage forms administered were not necessarily identical to the actual marketed forms. Therefore, the differences were probably due to variations among dosage forms. However, the DDI study was conducted under the same conditions for the single drug and the combination drug, and the analysis in this study included the ratio of absorption rates (ka ratio) obtained from these studies. In other words, even when ROS blood concentrations varied slightly from study to study, they could be included in the analysis as long as the study conditions were the same for the single and combination doses.

In the presence of OSI and ROX, the ke1 of ROS was 0.86 and 0.88-fold lower than that of ROS alone (Table 1). ROS is taken up into the liver by OATP1B1 and excreted in bile.7) Since ROX has been reported to inhibit the transport activity of OATP1B1 with an IC50 of 2.59 µM,6,25) it is likely that the inhibition of ROS uptake by ROX reduced hepatic uptake of ROS by OATP1B1 and delayed ROS excretion. Although OSI has not been reported to inhibit transporters in the hepatic uptake system, it may inhibit uptake of ROS in a manner similar to ROX. The results of DDI using OSI might be considered a special case, because the inhibitory form of OSI against BCRP may be different from that of other inhibitors, as described above.

The correlation between the C/M ratio of ROS in Caco-2 cells and the rate of change of ka obtained by clinical analysis (ka ratio) was examined, and a significant positive correlation was found (Fig. 3A, equations (5), (6)). This suggests that the results of the Caco-2 study allow quantitative estimation of drugs that produce DDI via ROS and BCRP in the gastrointestinal tract. No significant correlation was found between the C/M ratio and the rates of change of ke1 and ke2 (Figs. 3B, C). Since Caco-2 cells, which are derived from the human gastrointestinal tract, were used in the in vitro study, it is considered that the PK parameters (ke1 and ke2), which indicate the process of elimination, did not show a significant correlation with the C/M ratio. Furthermore, no significant correlation was observed between the C/M ratio and the rate of change of AUC (Fig. 3D), suggesting that the AUC is a complex parameter that describes absorption and elimination processes, and therefore, the correlation with the C/M ratio was poor.

AUCDDI,sim calculated using equations (4) and (6) showed a significant positive correlation with the AUCDDI,obs (R = 0.896, Fig. 4A), but was underestimated compared to AUCDDI,obs and the expected value of AUCDDI (AUCDDI,expected) was corrected as in equation (7) (Table 2).

| (7) |

| kaDDI,sim (h−1) | kaDDI,sim/kaalone (h−1) | AUCDDI,sim (ng·h/mL) | AUCDDI,expected (ng·h/mL) | AUCDDI,expected/AUCalone (ng·h/mL) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUC | 1.30 | 0.59 | 192 | 299 | 1.56 |

| TOL | 0.33 | 0.92 | 25 | 38 | 2.00 |

| FEB | 0.35 | 0.97 | 48 | 74 | 1.72 |

| FOS | 0.35 | 1.03 | 129 | 200 | 2.13 |

| ROX | 0.37 | 1.06 | 77 | 119 | 1.75 |

| CAP | 0.69 | 1.23 | 86 | 134 | 1.72 |

| OSI | 0.96 | 1.71 | 151 | 235 | 1.79 |

kaDDI,sim of ROS with BCRP inhibitors (RUC, TOL, FEB, FOS, ROX, CAP and OSI), AUCDDI,sim and AUCDDI,expected were obtained by equations (6), (4), and (8) respectively.

This AUCDDI,expected showed a good correlation with AUCDDI,obs (R = 0.895, Fig. 4B).

Equations (4) to (7) can be summarized as follows.

| (8) |

The results indicate that kaDDI,sim and AUCDDI,expected may be estimated from the pharmacokinetic parameters of ROS administered alone and the C/M ratio obtained using Caco-2 cells, even without conducting clinical study for DDI. In the present simulation, only kaDDI,sim was assumed to vary and the other parameters (A, B, ke1, ke2) were assumed to remain unchanged in order to simplify the calculation. Moreover, the coefficients in equation (8) have no scientific meaning, they are simply constants obtained from experimental results. However, in reality, these parameters may also vary when inhibitors are used in combination, and it was considered that simple simulations have limitations when accurately reproducing complex biological interactions. It is expected that more accurate predictions will become possible in the future as the results of clinical study of DDI in ROS are accumulated.

The present method may be useful not only for ROS but also for predicting BCRP-mediated DDI of other BCRP-substrate drugs. However, it is important to consider the membrane permeability of the test drug when investigating the correlation between the sensitivity to the transporter obtained by in vitro studies and its effect on clinical pharmacokinetics. Drugs classified as class 1 in the Biopharmaceutics Drug Disposition Classification System (BDDCS), have high membrane permeability and their gastrointestinal absorption is expected to be mainly influenced by passive diffusion rather than transporter-mediated delivery.26) In fact, apixaban (API), which is classified as BDDCS Class 1, is a substrate drug for the intestinal efflux transporters (P-glycoprotein (P-gp) and BCRP) in in vitro studies.27,28) Inhibitors of P-gp and BCRP have no effect on PK of API in clinical study.29) On the other hand, since ROS is classified as a BDDCS class 3 (highly soluble, low membrane permeability) drug,30) the membrane permeation process is the rate-limiting step for the gastrointestinal absorption of ROS, which may easily be affected by the transporters and their inhibition. These considerations suggest that it is important to prioritise drugs with low membrane permeability when predicting BCRP-mediated DDI in the gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, the present study confirmed that BCRP inhibitors significantly increased the intracellular accumulation of ROS in in vitro studies using Caco-2 cells. The C/M ratio of ROS obtained by the in vitro study and the ka ratio obtained by clinical analysis showed a significant positive correlation. Therefore, the C/M ratio obtained by the in vitro study using Caco-2 cells could describe the ka ratio in clinical analysis, suggesting that the BCRP-mediated DDI with ROS in the gastrointestinal tract could be quantitatively estimated. Furthermore, our method may be useful not only for ROS but also for predicting BCRP-mediated DDI of other BCRP-substrate drugs.

The authors thank to all the staff members of the Laboratory of Biopharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Takasaki University of Health and welfare. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.