2015 Volume 79 Issue 6 Pages 1156-1163

2015 Volume 79 Issue 6 Pages 1156-1163

The post-cardiac arrest syndrome is a complex, multisystems response to the global ischemia and reperfusion injury that occurs with the onset of cardiac arrest, its treatment (cardiopulmonary resuscitation) and the re-establishment of spontaneous circulation. Regionalization of post-cardiac arrest care, utilizing specified cardiac arrest centers (CACs), has been proposed as the best solution to providing optimal care for those successfully resuscitated after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. A multidisciplinary team of intensive care specialists, including critical care/pulmonologists, cardiologists (general, interventional, and electrophysiology), neurologists, and physical medicine/rehabilitation experts, is crucial for such centers. Particular attention to the timely initiation of targeted temperature management and early coronary angiography/percutaneous coronary intervention is best provided by such CACs. A State-wide program of CACs was started in Arizona in 2007. This is a voluntary program, whereby medical centers agree to provide all resuscitated cardiac arrest patients brought to their facility with state-of-the-art post-resuscitation care, including targeted temperature management for comatose patients and strong consideration for emergent coronary angiography for all patients with a likely cardiac etiology for their cardiac arrest. Survival improved by more than 50% at facilities that became CACs with a commitment to provide aggressive post-resuscitation care to all such patients. Providing aggressive, post-resuscitation care is the next real opportunity to increase long-term survival for cardiac arrest patients. (Circ J 2015; 79: 1156–1163)

Over the past decade, significant improvements in survival rates after cardiac arrest have been reported.1–9 Several new approaches, including minimally interrupted chest compressions,1–5,7 use of adjuncts to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR),6 and innovative public defibrillation programs8 have all produced increased survival compared with historical controls. More attention to earlier links in the “Chain of Survival” has led to a renewed emphasis on improving early detection and recognition, particularly by emergency dispatch personnel.10–12 Propagation of chest compression-only (“hands-only”) CPR has encouraged more bystander participation and some communities have not only increased the incidence of bystander CPR, but have increased survival as well.7 New ways to achieve earlier defibrillation has resulted in more survivors among those with shockable rhythms.8 After years of stagnant and dismal cardiac arrest survival rates, more and more out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) victims are now successfully resuscitated and bought to the hospital for further care. The final link in the Chain of Survival, the link of Post-Resuscitation Care, has now become increasingly important as the next real opportunity to improve long-term survival after OHCA.

Negovsky was the first to describe post-resuscitation disease in 1972.13 He described many of the different organ system’s pathophysiological changes that occur following resuscitation from cardiac arrest, but of particular interest is his description that “changes in cardiac function in the early recovery (period) depend to a considerable extent on the regional circulation in the myocardium”. Now, 43 years later, we are advocating early coronary angiography (CAG) for resuscitated victims of OHCA to assure that any culprit coronary vessel is identified and treated to decrease myocardial damage and to prevent subsequent cardiovascular complications.14

The importance of post-resuscitation care, this “second step in resuscitation” according to Negovsky,13 has been rediscovered and was the topic of a consensus statement from the International Liaison Committee for Resuscitation (ILCOR) in 2008.15 That report summarized the state of the art concerning post-resuscitation pathophysiology and coined a new term, “post-cardiac arrest syndrome”. Within this syndrome are 3 major areas of emphasis: (1) post-cardiac arrest brain injury; (2) post-cardiac arrest myocardial dysfunction; and (3) systemic ischemia-reperfusion (IR) response. When combined, these processes result in the majority of successfully resuscitated cardiac arrest victims dying in hospital rather than returning to their homes. Numerous studies have found a hospital mortality rate among those initially resuscitated of 65–75% (Table 1).16–21 The effect of early decision-making concerning poor expected outcomes, and resultant orders to limit additional care or even withdrawal support, is a recognized contributor to these high hospital mortality rates. The value of this consensus statement is the summary of the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and potential treatment options for this increasingly recognized syndrome. Improved outcomes following such treatments are the basis for the current hope that post-cardiac arrest care is the next real opportunity to restore more victims of cardiac arrest to their previous functional status.

| Study | n | OHCA/IHCA | In-hospital mortality rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| OPALS16 | 766 | OHCA | 65% (498/766) |

| Canadian CCRN17 | 1,483 | OHCA | 65% (964/1,483) |

| UK study18 | 8,987 | OHCA | 71% (6,381/8,987) |

| Norwegian study19 | 2,051 | OHCA | 55% (1,128/2,051) |

| Swedish study20 | 3,853 | OHCA | 72% (2,774/3,853) |

| NRCPR21 | 19,819 | IHCA | 67% (13,279/19,819) |

| Summary | |||

| OHCA | 17,141 | 69% (11,745/17,141) | |

| IHCA | 19,819 | 67% (13,279/19,819) | |

IHCA, in-hospital cardiac arrest; NRCPR, National Registry of CPR for In-hospital Cardiac Arrest (operated by the American Heart Association); OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Central nervous system injury is the most common cause of death following resuscitation from OHCA. Approximately two-thirds of deaths occurring after initial resuscitation are attributed to brain injury.22 Multiple drug treatments, including barbiturates and calcium-channel antagonists, failed to have an impact on this major sequela of cardiac arrest23,24 until the application of therapeutic hypothermia post resuscitation.25,26

Targeted Temperature ManagementAfter decades of promising experimental data, 2 randomized, clinical trials of therapeutic hypothermia were published in 2002. Both the European HACA trial25 and the Australian Bernard trial26 showed improved outcomes after the post-resuscitation application of cooling to 34℃ for 12–24 h. Though relatively small in size, both reports showed an improvement in long-term outcome among post-cardiac arrest patients. This was the first evidence that the post-resuscitation link in the Chain of Survival could actually affect survival.

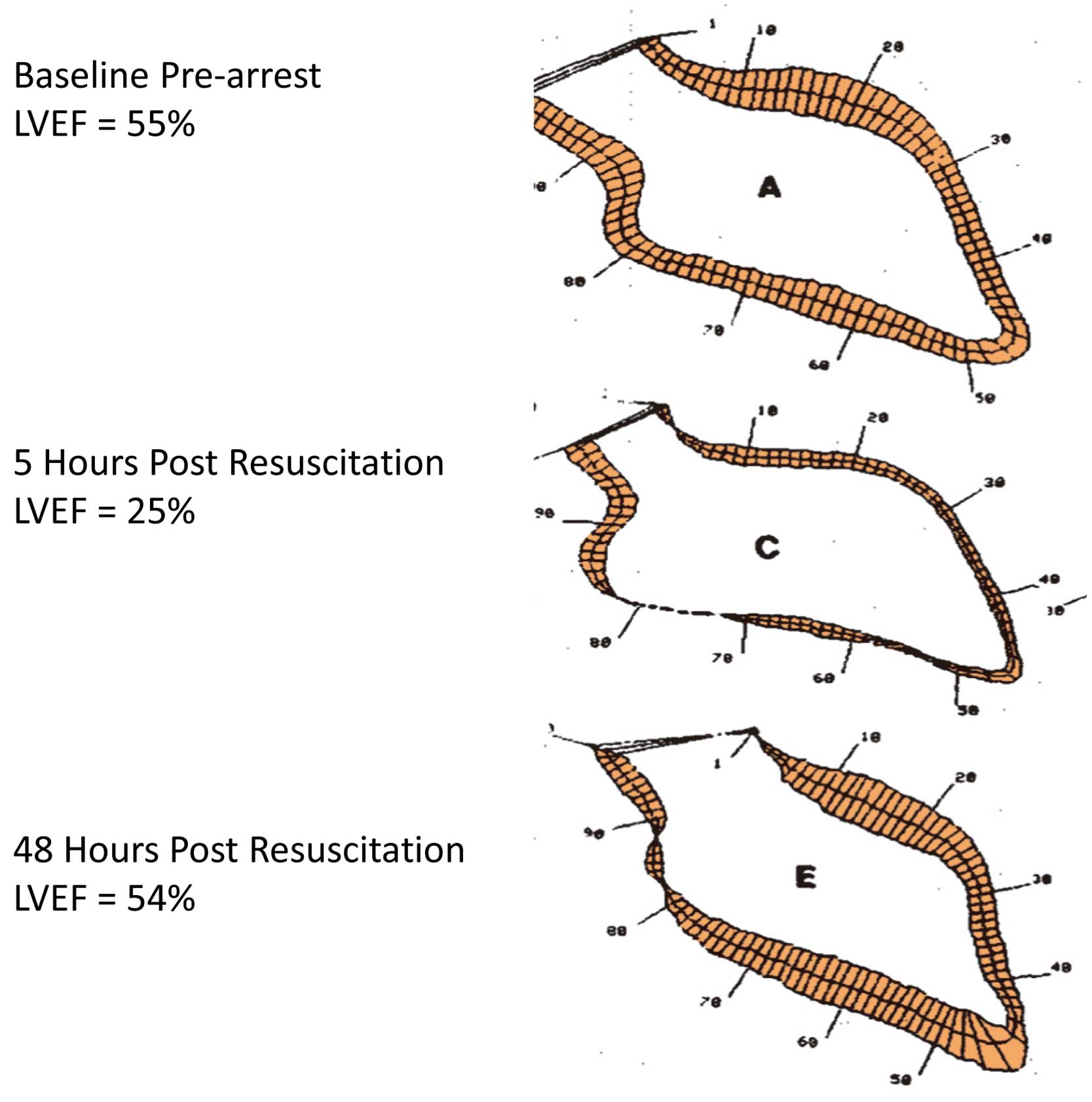

Post-Cardiac Arrest Myocardial DysfunctionMyocardial dysfunction is common post-cardiac arrest. Much like regional myocardial stunning following a period of coronary no-flow followed by reperfusion, cardiac arrest results in global myocardial stunning with both systolic and diastolic function abnormalities. Diffuse, global hypokinesis of both left and right ventricular contraction occurs,27–29 with dramatic decreases in ejection fraction, increases in end-diastolic filling pressures, and prolongation of isovolumic relaxation time. This dysfunction is generally transient and can fully recover within several days to a week, suggesting that this is myocardial stunning and not infarction21 (Figure 1). However, myocardial dysfunction can be severe and, if left unrecognized and untreated, can be life threatening. Post-resuscitation myocardial dysfunction responds well to inotropic medications, such as dobutamine. Moderate doses of intravenous dobutamine (5–10 μg/kg) have completely reversed such dysfunction in animal studies.30

Post-resuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Contrast left ventriculograms before and after prolonged ventricular fibrillation cardiac arrest in an experimental model (swine) demonstrating post-resuscitation myocardial dysfunction. Note full recovery of LVEF 48 h post resuscitation. LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. Reproduced with permission from Kern KB, et al.27

The vast majority of adults suffering OHCA (≈70%) have coronary artery disease (CAD).31 Most often, cardiac arrest appears to be an acute manifestation of CAD. Indeed, some now view OHCA as the most severe form of all acute coronary syndromes (ACS). As with all severe forms of ACS, CAG is helpful in identifying the culprit vessel and lesion, and should be considered early in the treatment course.

Early Coronary AngiographyMany ‘before and after’ observational cohort studies have shown that early CAG post cardiac arrest can improve survival.32 The average survival rate among these studies is 60%, compared with 25–30% among historical control groups.33 Most importantly, over 85% of such survivors have favorable neurological recovery and return to independent and functional lives.33 Both the European Society of Cardiology and the combined American College of Cardiology Foundation and American Heart Association have published recent guidelines for the treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). These guidelines strongly recommend [Class 1 recommendation] that immediate CAG and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), when indicated, should be performed in resuscitated OHCA patients whose initial ECG shows STEMI.34,35 There is more uncertainty about the value of early CAG for the post-resuscitated patient without ST elevation; however, the European Society of Cardiology still recommends [Class IIa recommendation] that “Immediate angiography with a view towards PCI should be considered in survivors of cardiac arrest without diagnostic ECG ST segment elevation but with a high suspicion of ongoing infarction”.34

A major landmark report solidifying the importance and value of post-resuscitation care appeared in 2007 from Oslo, Norway. Sunde and colleagues36 had noted the same poor general outcome of those resuscitated and brought to the hospital for post-cardiac arrest care. Their 1-year survival rate was only 26% among those who were initially resuscitated from OHCA and admitted to their university hospital. This was similar to many other facilities throughout the world, but they decided they could, and must, do better. A formal post-resuscitation treatment protocol was developed and agreed upon by all who cared for such patients. Their protocol called for each patient to receive therapeutic hypothermia (if comatose), early CAG, hemodynamic support (if hypotensive or in shock), rapid weaning from mechanical ventilation, and careful control of hyperglycemia. Within a few years, their survival rate for these patients increased to 56%, more than double the previous rate. These same authors continued to follow their post-resuscitation care protocol and found that 5 years later they had almost identical long-term survival rates (57%) with excellent neurological outcomes in nearly all survivors. A remarkable 91% of survivors achieved a cerebral performance category (CPC) of 1 or 2 (Figure 2).

Survival to hospital discharge before and after a formalized protocol for post-resuscitation care. Prior to formalizing post-resuscitation care, the survival-to-discharge rate was only 26% but after such a protocol was established, survival increased to 56%. A follow-up report 4 years later found similar survival rate of 56%, with 91% of those surviving having favorable neurological function (CPC 1 or 2). CPC, cerebral performance category; pre, pre-protocol; post, post-protocol.

Over time, it has become apparent that the 2 most important treatments in this bundled care approach are (1) therapeutic hypothermia and (2) early CAG and PCI. The other 3 features of this bundled approach either remain unproven or subsequently have been shown not to be helpful.

Hemodynamic Support for Hypotension and ShockDespite the data showing dobutamine infusion dramatically improved systolic and diastolic dysfunction post-resuscitation, no experimental or clinical study to date has shown such treatment improves outcome. In their recent review prior to the publication of the 2010 CPR guidelines, the International Liaison Committee for Resuscitation37 concluded, “No individual drug or combination of drugs has been demonstrated to be superior in the treatment of post-cardiac arrest cardiovascular dysfunction”. Despite improving hemodynamic values, no survival benefit from the use of inotropes and vasopressors in the post-cardiac arrest patient has ever been shown.37

Rapid Weaning From Mechanical VentilationIn accordance with good practice in critical care and pulmonary medicine, rapid weaning and extubation remain important goals post resuscitation. Such steps have been shown to decrease complications in the critically ill, particularly ventilator-related infections and barotraumas. However, no specific study in the post-resuscitated population has been reported. Pneumonia is a recognized frequent complication in comatose post-cardiac arrest patients, afflicting nearly half of all those resuscitated from OHCA. One cohort study suggests that prophylactic antibiotics may be useful post resuscitation.38

Treatment of HyperglycemiaHyperglycemia has been associated with poor neurological outcome after OHCA.33,34 Tight control of blood glucose (80–110 mg/dl) with insulin has been reported to reduce hospital mortality in critically ill adults in a surgical ICU.32 This created interest in tighter glucose control in the post-resuscitated, because hyperglycemia is common after cardiac arrest. Unfortunately, randomized trials of tighter glucose control from cardiac arrest have failed to show improved survival.39 Overshooting the goal was common, resulting in episodes of moderate hypoglycemia (<54 mg/dl) in 18% of patients. No difference in mortality was found with strict glucose control measures. Currently, the consensus is to forgo intensive insulin therapy after resuscitation from OHCA due to concern about needless production of hypoglycemic episodes.

It appears the 2 most effective treatments for the post-resuscitated victim of OHCA remain the use of mild therapeutic hypothermia and early CAG with PCI where indicated.

It is now clear that post-resuscitation care can affect long-term survival and the neurological recovery and function of survivors. The challenge has become to ensure that all resuscitated cardiac arrest patients receive this important therapy. Once delivered to the hospital, these patients typically are cared for by a variety of healthcare providers, including those from emergency medicine, cardiology, critical care/intensive care, pulmonary, neurology, and physical medicine/rehabilitation. Within this cadre of medical providers, wide variations in approach and enthusiasm for post-resuscitation therapies can exist. The second major challenge is the ability of the medical facility to provide such post-cardiac arrest care 24 h a day, 7 days a week. Many facilities do not have that capacity. These challenges have led to the concept of “cardiac arrest centers (CACs)”.

A regional center of care is not a new idea. Trauma centers rose to prominence in the USA in the 1980 s as the way to provide specialized care for serious trauma victims, while attempting to manage finite resources by avoiding unnecessary duplication of such care. As evidence supporting post-resuscitation care continued to mount, the concept of specialized CACs began to take hold. In an editorial in early 2005, Lurie, Idris and Holcomb noted that the trauma center model was a good one to consider for extending lifesaving post-cardiac arrest care to more patients and communities.40 These authors highlighted that a functional trauma center is not just a medical facility, but rather a specialized team of providers, each with important roles to fulfill in a time-sensitive fashion if optimal care is to be delivered. Other aspects crucial to the success of the best trauma centers are data collection and continuous quality improvement efforts. Cardiac arrest is a unique form of “trauma” to the entire body and specialized CACs patterned after successful trauma centers look to be the best way forward. This was a novel idea in January 2005. However, within several years others, including the American Heart Association, were becoming more and more interested in this concept.

A couple of years after the ILCOR Consensus statement “Post-Cardiac Arrest Syndrome” was published,15 the American Heart Association (AHA) published a policy statement supporting the idea of regional systems of care for OHCA.41 Recognizing the success of public health initiatives such as regional systems of care for STEMI patients as well as trauma patients, this statement strongly supported a similar effort and development of a regional system of care for the cardiac arrest victim successfully resuscitated in the field and then brought to the hospital. At the time of this statement, though the concept for such systems was well received, very few communities had implemented such a system. The notable exceptions were in Arizona, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Texas, and Virginia. No outcomes data from this approach had been reported at that time, so the report focused on how to overcome barriers to local implementation of CACs. Such barriers can include lack of knowledge, experience, personnel, resources and infrastructure.41 The authors provided a list of important elements for a successful “Cardiac Resuscitation Center” including: (1) EMS Medical Director involvement; (2) cardiac catheterization and PCI availability 24/7; (3) intensive care nursing and ancillary support; (4) multidisciplinary medical team approach to care; (5) community education and CPR training program; (6) data collection and analysis plan and capability; and (7) reimbursement strategy. These authors proposed 2 levels of CAC, namely, Level-2 centers that accept and stabilize, and then transfer to Level-1 centers any post-cardiac arrest patients who are candidates for hypothermia and early CAG. They conclude their report with a call for action, to develop and implement standards for regional cardiac arrest systems of care which should have a significant effect in improving long-term outcomes after cardiac arrest. Just 1 year later, the AHA published a consensus statement on implementing strategies for improving survival after OHCA.42 A key portion of that statement dealt with the role of post-resuscitation care in improving outcomes. The statement noted that, although therapeutic hypothermia has provided proof of concept that post-resuscitation therapy could affect long-term survival rates, comprehensive post-resuscitation care involves much more than just temperature management. Providing that comprehensive care for every resuscitated post-cardiac arrest care is the challenge but also the impetus behind the establishment of CACs.

One Example of a Successful Cardiac Arrest Center ProgramArizona began a program to develop CACs in 2007. In truth, the initial steps occurred 3 years earlier as community efforts to improve OHCA survival rates with chest compression-only CPR for lay bystanders.2,7 After years of translational research by the University of Arizona Sarver Heart Center resuscitation research group, the concept emerged that uninterrupted chest compressions were the most important aspect for a successful resuscitation.43–47 With the enthusiasm of the Tucson Fire Department, programs of chest compression-only CPR education and training were begun for both lay public and professional EMS providers in 2003. The early success in Tucson quickly translated to expanding the program to other parts of the State of Arizona. Every community doubled or tripled their survival rates within a year of adopting this new approach.2,7 With more cardiac arrest victims being successfully resuscitated, a new opportunity became apparent. In-hospital post-resuscitation care took on new meaning with this increase in resuscitated OHCA victims. Post-cardiac arrest care was being performed in some medical centers, but certainly not in the majority. In 2007, the State EMS Director organized a consortium to develop components of a CAC. An expanded list of major criteria is shown in Table 2. The goal of this effort was to extend promising post-resuscitation therapies to a larger proportion of the citizens of Arizona who were resuscitated from OHCA.

| In order to be recognized as a Cardiac Receiving Center, a hospital must have: |

| 1) A TTM method and associated protocol for OHCA patients |

| 2) Primary 24/7 PCI capability with protocol for OHCA, including consultation with a Cardiology Interventionist for consideration of emergency PCI |

| 3) A system, included in the protocol, for timely completion of the data form for EACH OHCA patient (NOT just cooled patients) and a data form for ALL EMS and ALL walk-in suspected STEMI patients. These forms are completed electronically on the CEDaR site |

| 4) An evidence-based termination of resuscitation protocol (including a 72-h moratorium on termination of care for patients receiving TTM). Sample wording available: http://azdhs.gov/azshare/documents/termination-of-resuscitation.pdf |

| 5) Daily EEG monitoring of post-cardiac arrest patients who undergo TTM to monitor neurological status. Daily EEG at a minimum, but continuous if available |

| 6) A protocol to address organ donation |

| 7) CPR training for the community (hands-only CPR or certification classes) |

| 8) 6 months of baseline OHCA data – please contact Margaret Mullins to receive access to the online data submission system. mjmullins@medadmin.arizona.edu (520-837-9590) |

| 9) At least 1 hospital representative involved in cardiac care attending the bi-annual Cardiac Center meetings to ensure all Cardiac Receiving and Referral Centers operate and maintain their recognition in a consistent manner. |

*From the www.azshare.gov website on March 3, 2015. CEDaR, Cardiac Event Data and Reporting; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; EEG, electroencephalography; EMS, emergency medical service; OHCA, out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction; TTM, targeted temperature management.

Once the basic criteria were defined, the Arizona Cardiac Arrest Center program was initiated by contacting key resuscitation stakeholders throughout the State. This included major medical centers and their leadership, leaders in emergency medicine, cardiology, critical care/intensive care medicine, emergency medical services, and community leaders. A website already in use for the SHARE (Save Hearts in Arizona Registry and Education) program (www.azshare.gov) was utilized as a resource for relaying program and protocol information to all interested parties. Hospitals fulfilling the designated criteria were offered personal presentations to explain additional details and answer any questions. The Arizona Cardiac Arrest Center program is entirely voluntary. There is no cost to join, but neither are there funds for participation. Hospitals desiring designation as a CAC were required to submit 6 months of OHCA data with a letter of agreement to fulfill all requirements, including to continue to submit data to the State-wide secure database.

Initial enthusiasm for becoming a State-recognized CAC was unexpectedly low. Only 2 medical centers pursued such designation during the first year of the program; both were the home institutions of the SHARE program leadership. In 2008, the SHARE group published a study that showed an independent association between survival after OHCA with witnessed arrest status, receipt of bystander CPR, the method of CPR, an initial shockable rhythm, and shorter EMS response times.48 However, there was no such association between survival and transport interval time (odds ratio=0.94; 0.51–1.8). This report led the Arizona EMS Council to approve a State-wide prehospital transport protocol allowing EMS providers to bypass the closest facility in favor of a designated CAC, if the additional travel time did not exceed 15 min. This protocol resulted in a distinct rise in applications for recognition as a CAC (Figure 3).

Initial growth of cardiac arrest centers (CACs) in Arizona. Prior to approval by the Arizona State Department of Health of an emergency medical service (EMS) protocol to bypass facilities to reach a designated CAC, the growth of such centers was slow, but substantial interest and growth occurred after the passage of the protocol.

The Arizona Cardiac Arrest Center program has continued to evolve and grow. A two-tiered system was developed, with Cardiac Arrest Receiving Centers and Cardiac Arrest Referral Centers. As of October 2014, there were 32 designated Cardiac Arrest Receiving Centers, covering nearly 80% of Arizona residents (Table 3).

| Arizona Heart Hospital – Phoenix |

| Arrowhead Hospital – Glendale |

| Banner Del E Webb Medical Center – Sun City West |

| Banner Desert Medical Center – Mesa |

| Banner Estrella Medical Center – Phoenix |

| Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center – Phoenix |

| Banner Heart Hospital – Mesa |

| Banner Thunderbird Medical Center – Glendale |

| Carondelet St. Joseph’s Hospital – Tucson |

| Carondelet St. Mary’s Hospital – Tucson |

| Chandler Regional Medical Center – Chandler |

| Flagstaff Medical Center – Flagstaff |

| Havasu Regional Medical Center – Lake Havasu City |

| John C. Lincoln Deer Valley Hospital – Phoenix |

| John C. Lincoln North Mountain Hospital – Phoenix |

| Kingman Regional Medical Center – Kingman |

| Maricopa Medical Center – Phoenix |

| Mayo Clinic Hospital – Phoenix* |

| Mercy Gilbert Medical Center – Gilbert |

| Mountain Vista Medical Center – Mesa |

| Northwest Medical Center – Tucson |

| Oro Valley Hospital – Oro Valley |

| Paradise Valley Hospital – Phoenix |

| Phoenix Children’s Hospital – Phoenix |

| Scottsdale Healthcare Osborn Medical Center – Scottsdale |

| Scottsdale Healthcare Shea Medical Center – Scottsdale |

| Sierra Vista Regional Health Center – Sierra Vista |

| St. Joseph’s Hospital – Phoenix |

| St. Luke’s Medical Center – Phoenix |

| Tucson Medical Center – Tucson |

| The University of Arizona Medical Center, South Campus – Tucson |

| The University of Arizona Medical Center, University Campus – Tucson* |

| Verde Valley Medical Center – Cottonwood |

| West Valley Hospital – Goodyear |

| Western Arizona Regional Medical Center – Bullhead City |

| Yavapai Regional Medical Center, West Campus – Prescott |

| Yuma Regional Medical Center – Yuma |

*Designates the inaugural members.

Do such programs fulfill the goal of extending post-resuscitation therapies to more patients? State-wide regionalization of post-cardiac arrest care in Arizona has resulted in an increase in the number of patients receiving both therapeutic hypothermia and CAG.49 The use of therapeutic hypothermia for post-arrest comatose patients increased from 0% (0/145 eligible) to 44% (300/682 eligible) in a comparison of State medical centers’ statistics before and after becoming a Cardiac Arrest Receiving Center. Likewise, the number of resuscitated patients undergoing CAG rose from 12% (17/145) to 31% (210/684). Though both therapies are provided significantly more often after the implementation of the CAC program, it is clear that further improvement is needed because the majority of resuscitated patients are still not receiving these 2 important post-arrest treatments.

Cardiac Arrest Centers and OutcomesThe most important issue surrounding the establishment of CACs is whether long-term outcomes are improved. In the Arizona experience, the modest increases in the use of post-resuscitation therapeutic hypothermia and CAG were associated with improved survival and favorable neurological outcomes.49 Survival nearly doubled among those with shockable rhythms and increased by more than 50% for all rhythms (Figure 4A). Survival with favorable neurological function also increased significantly (Figure 4B).

(A,B) Improved outcomes after instituting State-wide cardiac arrest centers (CACs). Both survival and survival with favorable neurological function increased in Arizona medical centers after their designation as CACs. After, designation as a CAC; Before, before designation as a CAC; OR, odds ratio; VF, ventricular fibrillation.

Post-resuscitation care is now recognized as a crucial component in achieving optimal long-term outcomes. The 2 most important aspects appear to be therapeutic hypothermia and early CAG with PCI, when indicated. Providing such therapies to all successfully resuscitated cardiac arrest patients remains a challenge. One successful approach is to designate CACs, where the commitment is high to provide such care 7 days a week, 24-h a day. A voluntary program instituted and maintained by the Arizona Department of Health and Human Services has successfully increased the delivery of post-resuscitation care throughout Arizona. Survival rates after institution of a program of selectively delivering resuscitated cardiac arrest victims to designated Cardiac Arrest Receiving Centers committed to provide such therapies have increased nearly 100%. Survival with favorable neurological function has also improved with this strategy.

The author serves as a scientific advisory board member for Zoll Medical Inc and Physio-Control Inc and is compensated for time spent in this role. Both companies have commercial interests in resuscitation therapies.