2021 Volume 85 Issue 6 Pages 948-952

2021 Volume 85 Issue 6 Pages 948-952

Background: Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) is a rare syndrome temporally related to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). MIS-C shares similarities with Kawasaki disease, but left ventricular dysfunction is more common in MIS-C.

Methods and Results: This study reports the case of a 16-year-old Japanese male patient with MIS-C. Although the initial presentation was severe with circulatory and respiratory failure, the patient recovered completely. Endomyocardial biopsy showed active myocarditis with fibrosis. Immunoglobulin treatment was useful for recovery.

Conclusions: This is the first reported case of MIS-C in Japan. Cardiologists should be aware of MIS-C, a new disease, occurring during the global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

A 16-year-old Japanese male patient was transferred to our intensive care unit (ICU) from a local hospital because he was experiencing shock. He had been in good health with no past medical history (symptomology or diagnosed health conditions) until January 2020, when he was diagnosed with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection (day 1). The diagnosis was confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from nasopharyngeal swab sampling after contact with a COVID-19 patient. The patient remained asymptomatic for 20 days after the confirmation of COVID-19 infection when he noted general fatigue and abdominal pain in the umbilical region, followed by an increase in temperature of up to 40℃, severe watery diarrhea, and the appearance of a skin rash on his whole body.

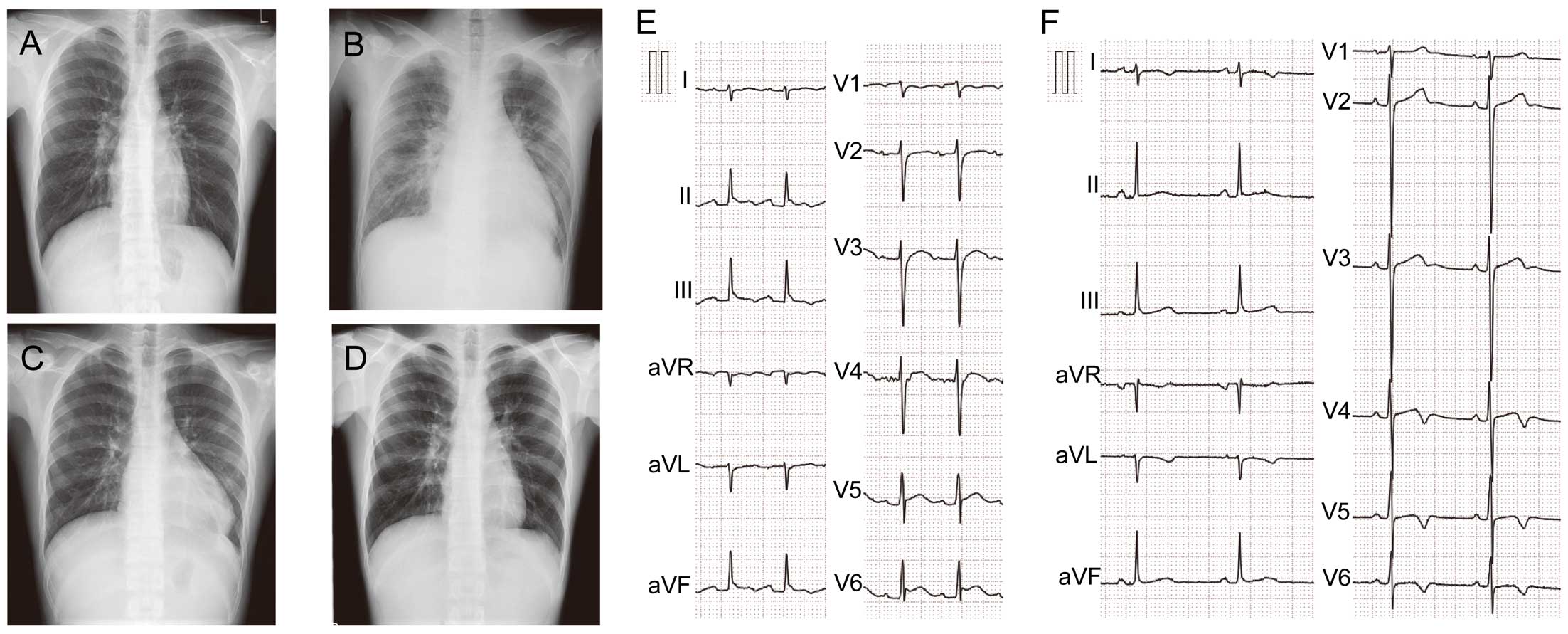

On day 23 after confirmation of COVID-19 infection, the patient was admitted to a local hospital. While a chest X-ray showed no abnormal findings (Figure 1A), he was suspected to have mesenteric lymphadenitis on the basis of an enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan, and empiric antibiotic therapy was started (ceftriaxone 2 g/day, then levofloxacin 500 mg/day and azithromycin 500 mg/day). However, his symptoms continued with little change, and his general condition progressively worsened during the 3 days of hospitalization. On day 26, he developed severe hypotension at an unmeasurable level and was transferred to our emergency department and ICU (ICU day 1).

Chest X-ray and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). Chest X-ray images on (A) day 23 after confirmation of coronavirus disease 2019 at the local hospital; (B) intensive care unit (ICU) day 1, (C) ICU day 10, and (D) ICU day 21. Parts (E) and (F) show the 12-lead ECG on ICU day 1 and ICU day 13, respectively.

On physical examination at our emergency room, the patient’s blood pressure was 100/66 mmHg with 4 μg/kg/min dobutamine support, with a heart rate of 103 beats/min, respiratory rate of 19 breaths/min, and blood oxygen saturation of 96% without supplementary oxygen support. His temperature was 37.1℃ at the initial measurement, but rapidly increased, and he continued to run a high fever up to approximately 40℃ beginning soon after admission. His breath sounds were normal, although the third heart sound was accentuated and a grade III systolic murmur was heard at the left margin of the sternal border and midclavicular line in the fifth intercostal space. He was alert, but anxious, and presented with asthenia.

He had a high fever for >5 days, a rash over his entire body (Figure 2A), and bilateral non-purulent conjunctival injection (Figure 2B), but there were no abnormal findings or symptoms of the lips and oral cavity, no cervical lymphadenopathy, and no extremity changes. He did not meet the criteria for Kawasaki disease.

Skin rash and bilateral non-purulent conjunctival injection. (A) Skin rash in the photographs of the abdomen and left upper and lower extremity from left to right. (B) Bilateral non-purulent conjunctival injection.

Laboratory findings showed elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP; 20.6 mg/dL), brain natriuretic peptide (711.3 pg/mL), creatinine (1.19 mg/dL), aspartate transaminase (40 U/L), procalcitonin (5.38 ng/mL), d-dimer (5.0 μg/mL), ferritin (294.0 ng/mL), fibrinogen (606.0 mg/dL), and prothrombin (with a time of 13.8 s), and decreased platelet count (13.0×104/μL) and albumin level (2.5 g/L). Troponin T levels were elevated (0.515 ng/mL), but the levels of creatine kinase (CK) and CK-MB were within normal limits (87 U/L and 7 ng/mL, respectively). The patient’s white blood cell count was 8,750/μL with a composition of 93.3% neutrophils, 4.1% lymphocytes, 1.3% monocytes, and 1.1% eosinophils. PCR obtained from nasopharyngeal swabs, serum, and stool were all negative, but serology was positive for immunoglobulin (Ig)M and IgG for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), suggesting that he had been in contact with the virus >3 weeks before admission.

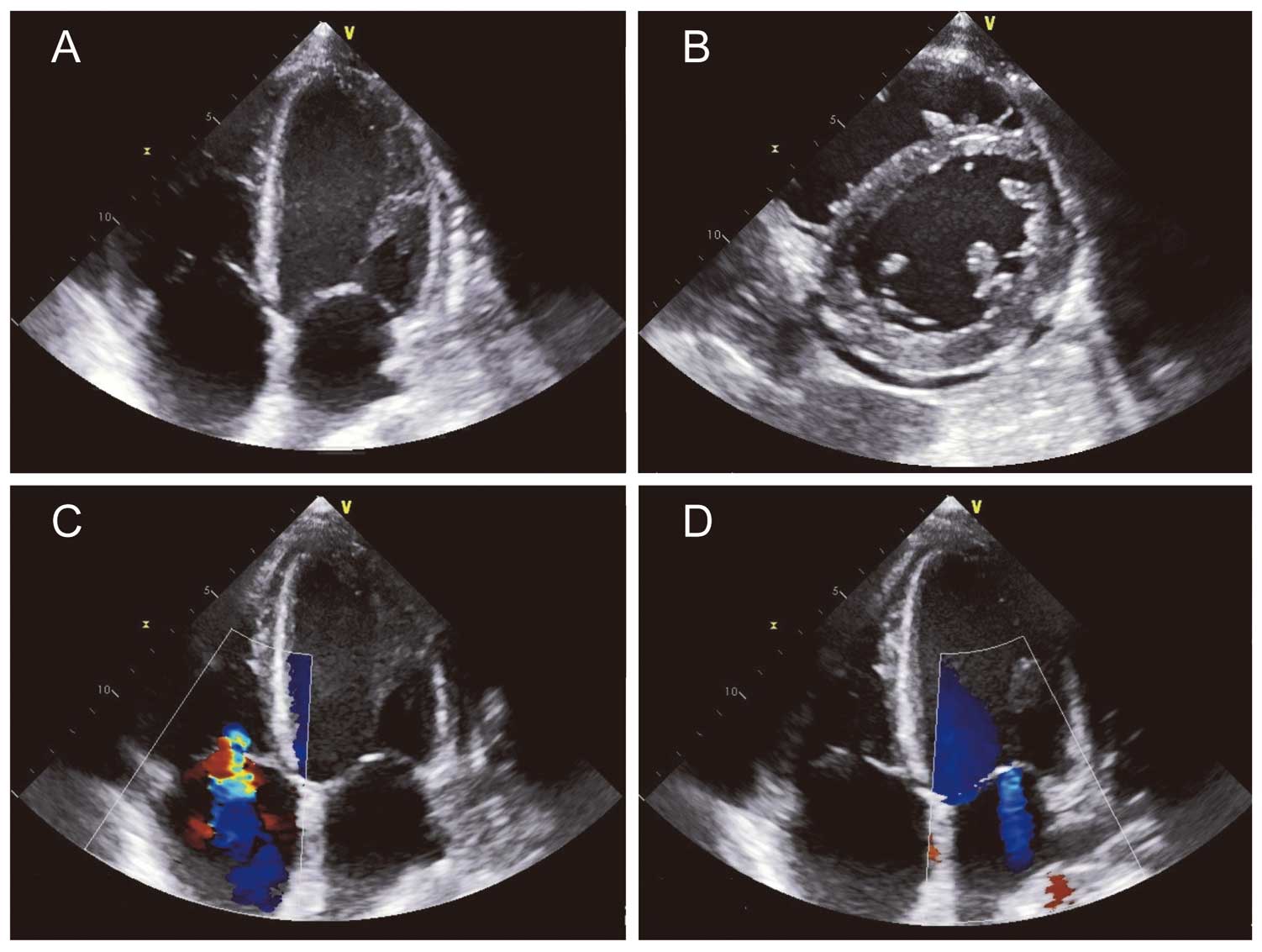

Chest X-ray revealed a marked increase in the size of the heart shadow, increased pulmonary markings, and bilateral pleural effusion (Figure 1B). A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed ST-segment elevation in leads II, III, aVF, and V4 through V6 (Figure 1E). Echocardiography revealed reduced left ventricular systolic function of <40%, hypokinesis of the right ventricle, enlargement of the right side of the heart (Figure 3A,3B), severe tricuspid regurgitation due to impaired tricuspid valve coaptation (Figure 3C), moderate mitral regurgitation (Figure 3D), and pericardial effusion (Figure 3B).

Echocardiography on intensive care unit day 1.

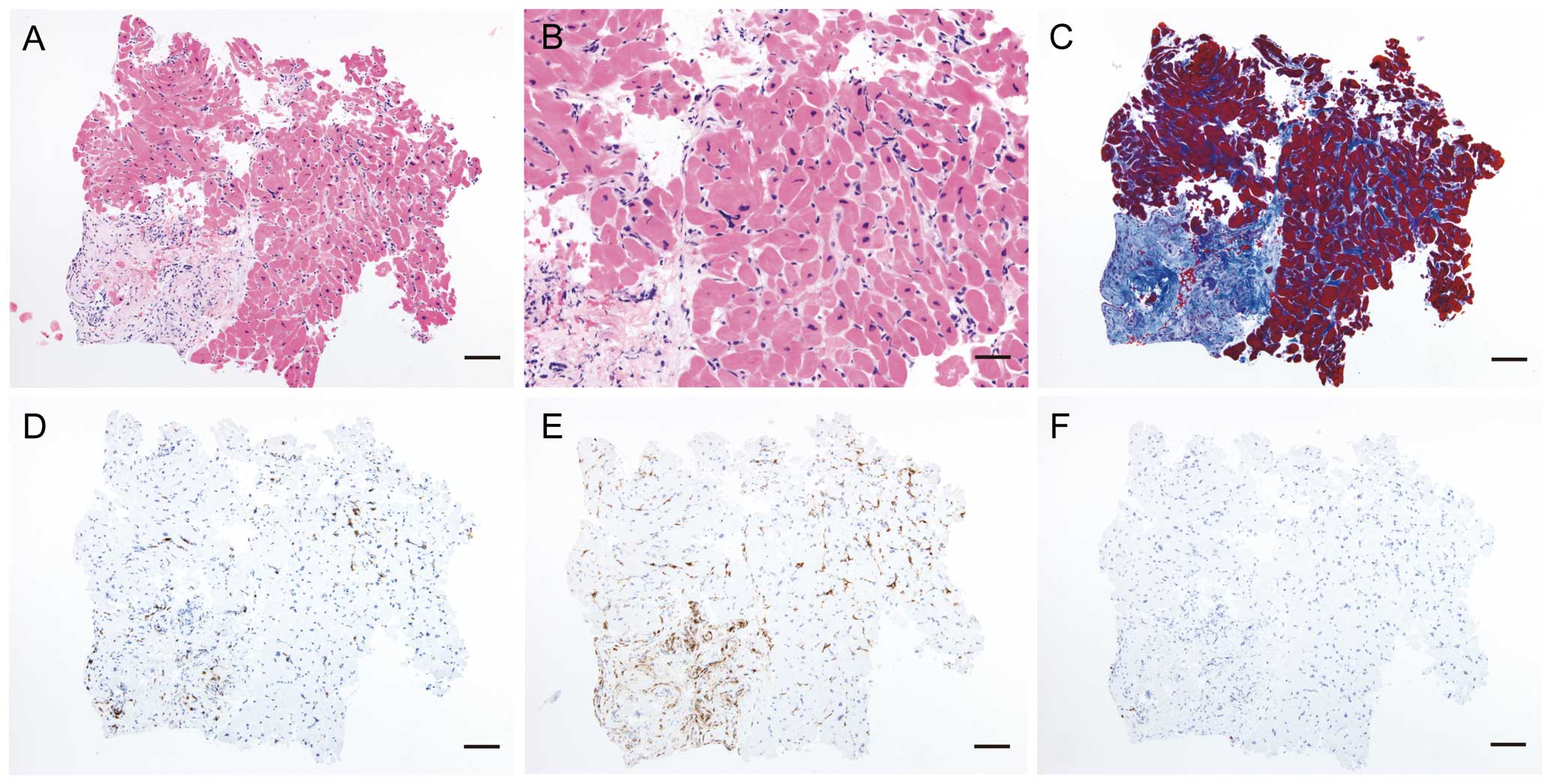

An emergency right ventricular endomyocardial biopsy on ICU day 1 showed interstitial mononuclear cell infiltration of the myocardium (Figure 4A,B). The cardiomyocytes were various sized, irregularly shaped, and exhibited swollen and hyperchromatic nuclei. These histopathological findings clearly indicated myocardial injury and degeneration. In addition to interstitial fibrosis between the cardiomyocytes, replacement fibrosis was also observed in the subendocardial region with some infiltration of eosinophils (Figure 4C). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the infiltrating cells were primarily CD3+ T cells with CD163+ macrophages; no CD20+ B cells were seen in the myocardium (Figure 4D–F, respectively). These histopathologic findings indicated active lymphocytic myocarditis with fibrosis.

Endomyocardial biopsy from the right ventricle. (A) and (B) Low-and high-power views, respectively, of the biopsy specimen with hematoxylin and eosin stain. (C) Azan stain for assessing fibrosis of cardiomyocytes. (D–F) Iimmunohistochemical staining for CD3, CD 163, and CD20, respectively. Bar scale: A and C–F, 100 μm; B, 50 μm.

We initially suspected viral myocarditis with cardiogenic shock and stopped all antibiotics after admission to the ICU. Due to the patient’s high inflammatory state, severe watery diarrhea, and the findings of pleural effusion and ascites, we noticed that the shock was not only associated with cardiac factors but also with hypovolemic and distributive factors. The blood pressure readings remained persistently low at approximately 70/40 mmHg after dobutamine support, and we added noradrenaline at 0.1 μg/kg/min on ICU day 1. The patient’s respiratory state gradually aggravated, and he was started on 1 L/min of oxygen by mask and an albumin dose of 25 g for 3 days; 20 mg/day of continuous furosemide infusion was started on ICU day 2. His blood pressure remained relatively low, although it was maintained at 90/50 mmHg, and the amount of urine output gradually increased after these therapies. Severe diarrhea and abdominal pain gradually improved, and echocardiography showed a slight improvement in left and right heart systolic function, enlargement of the right side of the heart, and severe mitral and tricuspid regurgitation day by day during the course of his 4 days of ICU stay, although the patient’s high fever and inflammatory state persisted.

A diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was confirmed on the basis of the history of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the patient’s symptoms and clinical course, and he received intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg; 2,000 mg/kg) on ICU day 5. The patient’s skin rash nearly disappeared the following day, and high fever and left and right ventricular systolic dysfunction improved rapidly after IVIg treatment, concomitant with a gradual decline in the inflammatory process. The use of noradrenaline, dobutamine, and oxygen was discontinued on ICU day 7, and furosemide was discontinued on ICU day 8.

A chest X-ray showed improvement in the findings of bilateral pleural effusion and congestion, and a decreased size of the cardiac shadow on ICU day 10 (Figure 1C), though the cardiac shadow was larger than that on day 23. A 12-lead ECG showed ST-segment elevation resolution in leads II, III, aVF, and V4 through V6, and inverted T wave in leads V4 through V6 on ICU day 13 (Figure 1F). Additionally, echocardiography showed normal systolic function and disappearance of pericardial effusion on ICU day 13. The patient was discharged from the ICU and was sent to the general ward for follow up for heart failure on ICU day 14. He showed a favorable post-ICU clinical course without any symptoms, and a chest X-ray showed further improvement in the decreased size of the cardiac shadow on ICU day 21 (Figure 1D). No serial changes were noted in the size of coronary arteries on echocardiography during the hospital stay. He was discharged from our hospital on ICU day 22.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of MIS-C associated with COVID-19 in a Japanese child. Moreover, this is the first report that shows evidence of active myocarditis with fibrosis by histopathological investigation with endomyocardial biopsy in a patient with MIS-C.

MIS-C is a rare syndrome that is temporally associated with previous exposure to SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 in children is thought to be relatively mild compared with adult patients, and children are often asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic.1,2 However, recent reports from Europe and North America have described a number of seriously ill children. In addition to cases that exhibit classic features of Kawasaki disease, heterogeneous manifestations of systemic inflammation and shock have been increasingly reported.3–6 These cases have been categorized as pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with COVID-19 (PMIS) by the Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health, and as MIS-C by the World Health Organization and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United States of America. There is no specific test available to diagnose MIS-C and validated diagnostic criteria do not currently exist. Hence, the diagnosis of MIS-C is based on characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, as well as evidence of a previous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Common features of MIS-C are high fever, acute heart failure complicated with shock, gastrointestinal symptoms, bilateral conjunctival injection, skin rash, and a presentation with asthenia, as described in our case.3–6 MIS-C is characterized by classic findings of inflammation with multi-organ dysfunction that not only involves the skin, mucous membranes, and heart, but also frequently affects the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and neurologic systems, although the full clinical continuum is still being defined.6–9 Endothelial dysfunction is thought to be central in the pathophysiology of both severe COVID-19 and MIS-C; however, recent studies have clarified the difference between the early infectious phase of severe COVID-19 and MIS-C.7–9 MIS-C is a post-infectious process with cases peaking 3–6 weeks after the highest rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection as measured by PCR positivity.3–10 Mesenteric lymphadenitis was reported in many cases as well as in our case, and emergency operation for suspected appendicitis was sometimes performed in the MIS-C diagnostic process.6 There is no specific finding in a 12-lead ECG in MIS-C.5,6 However, the 12-lead ECGs of our patient showed ST-segment elevation and resolution during the clinical course. The serial changes noted in the 12-lead ECGs in this case might reflect the acute inflammation and attenuation of myopericarditis.

Initial reports have emphasized similarities in clinical and immunological features between MIS-C and Kawasaki disease; however, recent reports suggest that MIS-C is a distinct entity that may have some overlapping features with Kawasaki disease, and a few children with MIS-C completely met the diagnostic criteria for a classic form of Kawasaki disease. Whether these diagnoses are distinct or represent a continuum of the same clinical syndrome remains to be determined.6–10 Notably, left ventricular dysfunction is the main and most common cardiac feature, with a limited number of MIS-C patients presenting with coronary artery dilatation.5–10 A majority of children with MIS-C have presented with shock requiring inotropic support, as in our case.3–10 However, shock or vascular compromise is rare with Kawasaki disease, affecting <10% of Kawasaki patients.11 These findings emphasize the importance of cardiac evaluation for all children with MIS-C.

Kawasaki disease predominantly affects young children aged <5 years, whereas the median age for children with MIS-C is 10 years.6–10 Additionally, the surprising absence of reported MIS-C illness in Asian countries, where Kawasaki disease is most prevalent, suggests that MIS-C and Kawasaki disease may represent distinct genetic predispositions.6–10 Myocardial inflammation has been documented in a high proportion of patients with Kawasaki disease and usually precedes coronary artery abnormalities.12 Myocardial involvement with acute heart failure in MIS-C is now thought to be due to myocardial stunning or edema rather than due to inflammatory myocardial damage.6–8 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no previous report involving histopathological investigation with endomyocardial biopsy among MIS-C patients. The right ventricular biopsy result of our patient provides histopathological proof of active myocarditis with fibrosis in MIS-C. Although our case findings showed evidence of right heart failure, to our knowledge, there is no reported case of right ventricular dysfunction in children with MIS-C. Left and right ventricular systolic dysfunction improved rapidly after IVIg treatment in our patient, concomitant with a decline in the patient’s inflammatory state, including reduced high fever, skin rash symptomology, and CRP levels. Furthermore, our case suggested that the causes of shock in MIS-C were mixed cardiogenic hypovolemic and distributive. This multiple etiology shock picture may be due to a combination of cardiac dysfunction, blood volume loss through severe watery diarrhea, insensible fluid loss due to high fever, and vasodilation due to a high inflammatory state.

Pediatricians, cardiologists, general physicians, and emergency and critical care providers should all be aware of this new disease, MIS-C, which shares similarities with Kawasaki disease but has specificities in its presentation. These specificities include a higher prevalence of acute heart failure complicated with shock in a broader age range of children with MIS-C compared to those with Kawasaki disease. Therefore, to aid in the diagnosis and treatment of MIS-C, there is a need for these communities to increase their awareness about MIS-C in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Early diagnosis of MIS-C, associated with COVID-19 and complicated with heart failure, is certainly useful in the present period to identify children who require treatment and to prevent left ventricular dysfunction and acute heart failure.6–10 The initial clinical presentation may be severe in some patients, requiring mechanical circulatory and respiratory assistance. However, as in our case, rapid recovery and favorable outcomes with inotropic support and the use of immunoglobulin, with or without adjunct steroids, have been currently observed in most children with MIS-C.3–10

We wish to acknowledge Dr. Hiroyuki Kanno, Professor of Pathology, Shinshu University School of Medicine, and Dr. Yoshikazu Yazaki, Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Saku Central Hospital, for their help with histopathological interpretation of the endomyocardial biopsy specimens.

K.K. is a member of Circulation Journal’s Editorial Team.

Shinshu University Hospital was granted an exemption from requiring ethics approval. Written informed consent for this report was obtained from the patient and his parents.