2019 年 67 巻 10 号 p. 1139-1143

2019 年 67 巻 10 号 p. 1139-1143

We have discovered that β-amino acid homooligomers with cis- or trans-amide conformation can fold themselves into highly ordered helices. Moreover, unlike α-amino acid peptides, which are significantly stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonding, these helical structures are autogenous conformations that are stable without the aid of hydrogen bonding and irrespective of solvent (protic/aprotic/halogenated) or temperature. A structural overlap comparison of helical cis/trans bicyclic β-proline homooligomers with typical α-helix structure of α-amino acid peptides reveals clear differences of pitch and diameter per turn. Bridgehead substituents of the present homooligomers point outwards from the helical surface. We were interested to know whether such non-naturally occurring divergent helical molecules could mimic α-helix structures. In this study, we show that bicyclic β-proline oligomer derivatives inhibit p53–MDM2 and p53–MDMX protein–protein interactions, exhibiting MDM2-antagonistic and MDMX-antagonistic activities.

β-Peptides form orderly secondary structures, as do α-peptides, and their resistance to proteolysis is advantageous, e.g., for the development of peptide drugs, including β-peptide-based antibiotics.1,2) The enhanced molecular flexibility of β-peptides results in great structural diversity,3) but conversely leads to difficulties in forming constrained conformations, and especially in controlling amide cis–trans isomerization.

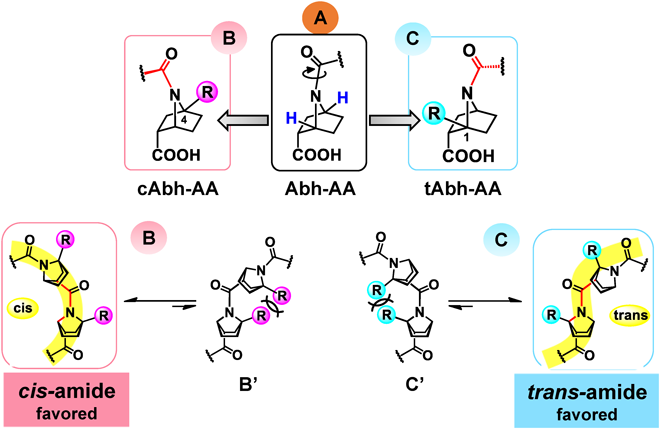

We have reported the synthesis of a bicyclic analogue of β-proline, 7-azabicyclo[2.2.1]heptanecarboxylic acid (Abh-AA, A, Fig. 1). We found that a bridgehead substituent at the C1- or C4-position in homooligomers of A can bias the cis–trans equilibrium: substituents at the C4-bridgehead position tip the equilibrium towards cis-amide conformation4) (cAbh-AA, B, Fig. 1), while introduction of substituents at the C1-bridgehead position causes complete switching to trans-amide conformation (tAbh-AA, C, Fig. 1), probably due to CNC angle strain or 1,3-allylic-type steric repulsion involving adjacent substituent groups5) (B′ and C′, Fig. 1). Our further structural studies revealed that homooligomers of either cis- or trans-amide can fold themselves into corresponding highly ordered helices.4–7) Moreover, unlike α-amino acid peptides, which are significantly stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonding, these helical structures are self-organized and conformationally stable without the aid of hydrogen bonding and irrespective of solvent (protic/aprotic/halogenated) or temperature. Combination of these bicyclic β-proline analogues and α-amino acids, that is, heterooligomers are also synthetically accessible, and the N-amide bond of these bicyclic β-proline analogues are reluctant to alkaline hydrolysis, indicating some metabolic stability.8,9) Furthermore, a shape similarity comparison of helical cis/trans bicyclic β-proline homooligomers with typical α-helical structure of α-amino acids reveals clear differences of geometry, such as pitch and diameter per turn (Fig. 2). While α-helix takes 3.6 residues/turn, cis-amide helix and trans-amide helix of β-proline homooligomers are estimated to take approximately 4 residues/turn and 2.7 residues/turn, respectively.4,5) Bridgehead substituents of the homooligomers point outwards from the helical surface.

(Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

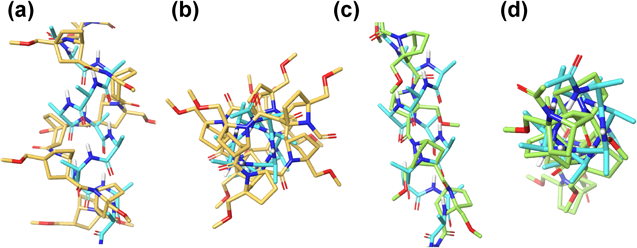

(a, b): Structural comparison of cis-amide helix with cAbh-AA (orange) and α-helix of α-alanine (light blue). (c, d): Structural comparison of trans-amide helix with tAbh-AA (green) and α-helix (light blue). A part of N terminus in tAbh-AA is not shown for clarity (d). (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

We were interested to know whether such non-naturally occurring divergent helical molecules can functionally mimic the α-helix. In this study, we show that bicyclic β-proline oligomer derivatives inhibit the protein–protein interaction of the tumor suppressor protein p53 with E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase (MDM2), thereby exhibiting MDM2-antagonistic activity. This is of interest because inhibition of MDM2–p53 interaction is a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of cancer.

p53 halts the cell cycle at its regulation point, activates DNA-repair mechanisms, and induces apoptosis of cells with irreparable DNAs. MDM2 is an important negative regulator of p53, forming an MDM2–p53 negative feedback loop in the cell. MDMX, a homolog from the same family, works in coordination with MDM2, exerting similar inhibitory regulation on p53.10) MDM2 amplification disequilibrates the p53–MDM2 balance and deactivates free p53, which may lead to cancer occurrence.11) Antagonists of MDM2 inhibit p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction, releasing p53 and activating its anti-tumor function. In this context, α-helix–α-helix interactions are frequently observed at protein–protein interfaces,2,12,13) and the p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction is considered to involve interactions between α-helix structures of p53 and MDM2/MDMX. Here, we investigated whether the non-naturally occurring helix of bicyclic β-proline oligomer derivatives can mimic α-helix structure sufficiently to interfere with the p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction, i.e., whether these derivatives represent a novel type of MDM2/MDMX antagonists.

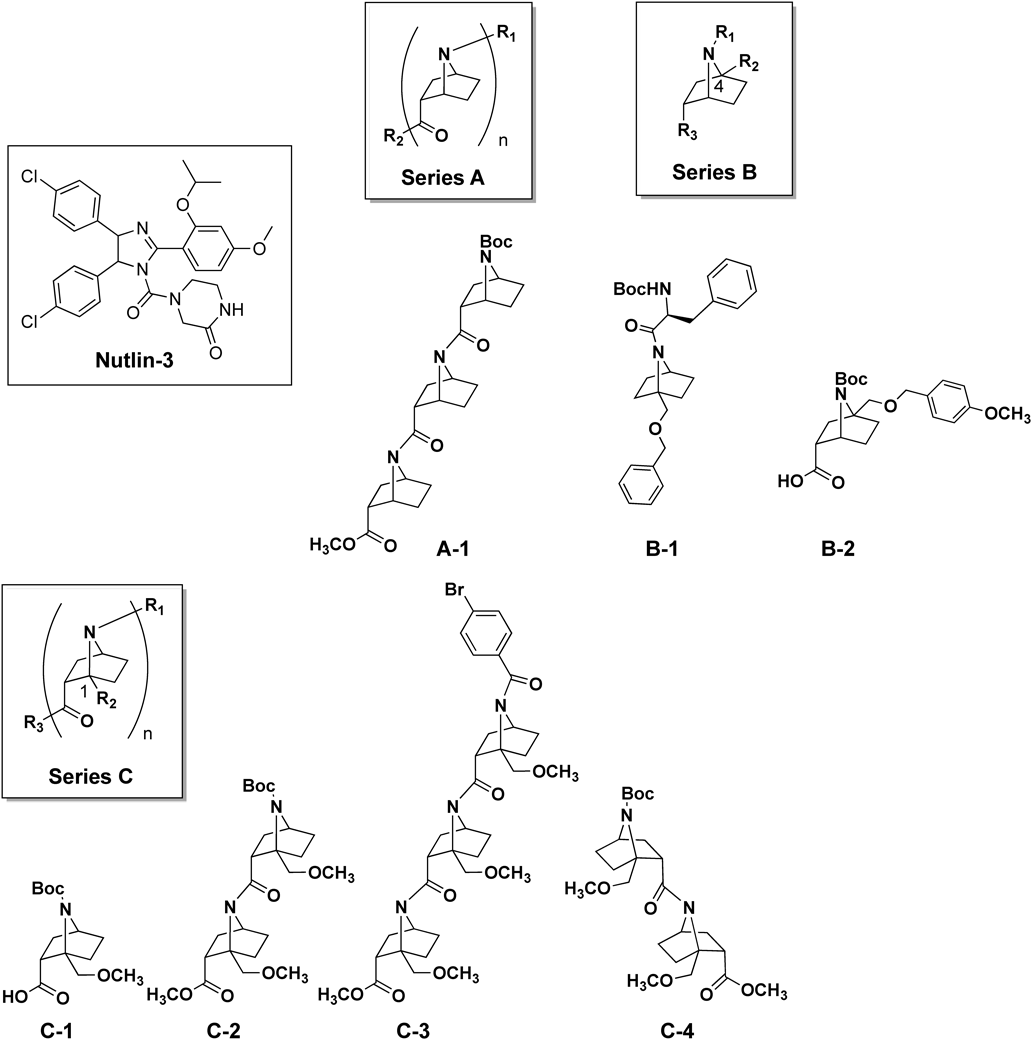

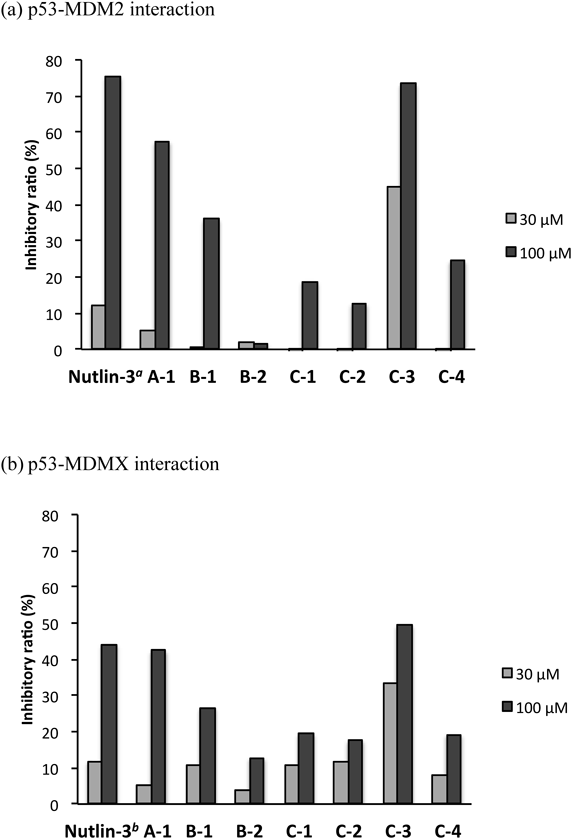

We selected seven structurally diverse compounds from our synthesized compound library of bicyclic β-proline amide oligomers (Fig. 3). These seven compounds (A-1, B-1, B-2, C-1, C-2, C-3, and C-4) can be divided into three series, that is, non-bridgehead-substituted Abh-AA homooligomer (A), bridgehead-substituted monomers (B) and tAbh-AA homooligomers (C). The biological activities of synthesized compounds were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), using glutathione S transferase (GST)-tagged MDM2 and MDMX proteins. Figure 4 illustrates the suppressive effects of these compounds on the p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction. We found that A-1 and C-3 both exhibited >50% inhibitory activity on the p53–MDM2 interaction at 100 µM, but only C-3 still showed acceptable activity at 30 µM (Fig. 4a). In the case of MDMX, all seven compounds showed weaker inhibition than towards MDM2, though C-3 still showed the strongest activity (Fig. 4b). In general, shorter oligomers (monomer or dimer: B-1, B-2, C-1, C-2 and C-4) showed little inhibition of the p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction. Further, although A-1 was inhibitory at 100 µM, it showed little inhibition at 30 µM. We attribute these results to the absence of bridgehead immobilization, which is important to maintain helicity. The observation that C-3, which forms a robust trans-amide-type helical conformation, was the most potent inhibitor may mean that a helix consisting of at least three bicyclic β-proline units is required to occupy the MDM2/MDMX binding site.

a Nutlin-3 was tested at 1 (gray bar) and 3 µM (black bar). b Nutlin-3 was tested at 10 (gray bar) and 30 µM (black bar). Compounds were tested in duplicate wells using the ELISA method. Representative assays are shown.

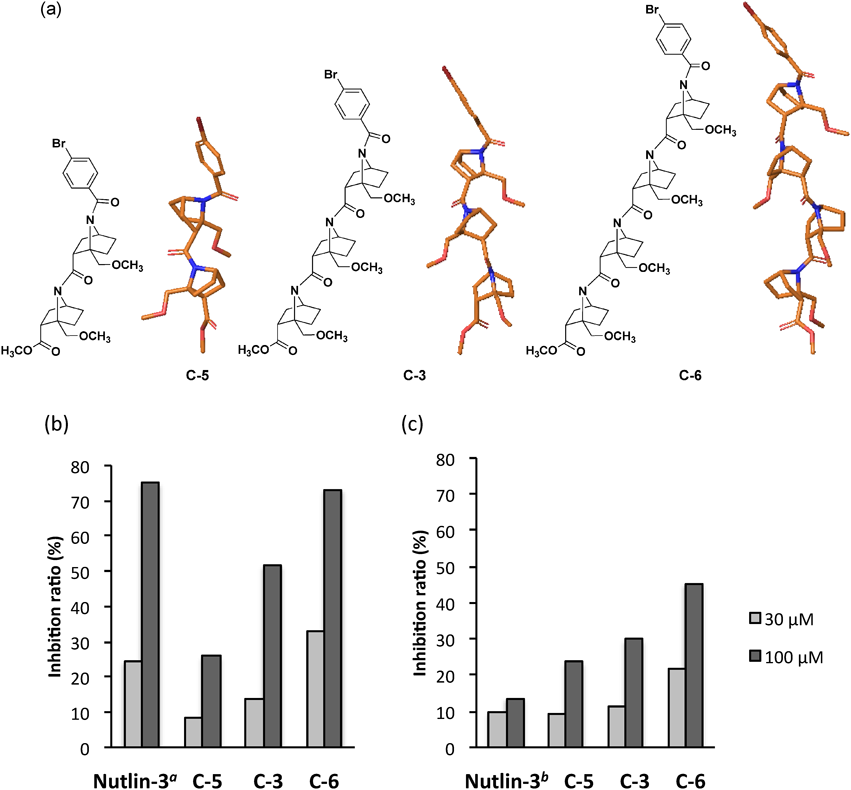

Next, in order to investigate the influence of helix length on inhibitory activity, we designed homooligomers with the same monomer unit as C-3 (Fig. 5). The dimer C-5 and tetramer C-6 were constructed and subjected to biological assay along with trimer C-3. As shown in Fig. 5, tetramer C-6 showed the greatest inhibitory activity, while trimer C-3 displayed much higher activity than dimer C-5, which gave poor results at both 30 and 100 µM.

a Nutlin-3 was tested at 1 (gray bar) and 3 µM (black bar). b Nutlin-3 was tested at 10 (gray bar) and 30 µM (black bar). Compounds were tested in duplicate wells using the ELISA method. Representative assays are shown. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

Thus, the inhibitory activity towards the p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction increases as the helical chain of homooligomers becomes longer. The trimer and tetramer turned out to be effective in inhibiting p53–MDM2/MDMX interaction. In other word, these two helical β-proline oligomers can likely occupy the binding site effectively. One of the representative docking poses was shown in Fig. 6. In this docking pose, hydrogen bonding is not involved between C-3 and MDM2, and electrostatic interactions are also of insignificance, judging from the non-polarized MDM2 binding pocket. Probably, hydrophobic interactions seemed to be crucial because the hydrophobic amino acid residues of the cavity of MDM2 are facing to the helical molecule C-3 (data not shown). π–π Interaction of N-p-bromobenzoyl group may be also involved with the tyrosine residue in the cavity of MDM2.

Non-polar hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Atom color: carbon atom: grey; nitrogen atom: blue; oxygen atom: red. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

We have evaluated the inhibitory activity of nine bicyclic β-proline homooligomer derivatives towards the p53–MDM2/MDMX protein–protein interaction. Among the compounds, C1-substituted bicyclic β-proline trimer C-3 and tetramer C-6, which take trans-helix conformations, significantly inhibited p53–MDM2/MDMX binding. We found that bicyclic β-proline analogs with a C1-substituent group predominantly take trans-amide conformation due to steric repulsion of the bridgehead groups; consequently, their oligomers form robust trans-amide helical structures that can effectively occupy the MDM2/MDMX binding site. Removal of the bridgehead substituents may cause partial loss of activity. In addition, a length dependency of trans-amide oligomers was discovered, in that the inhibitory activity increases from dimer to tetramer. Further structural optimization and studies to establish the binding modes of the antagonists are in progress.

Author ContributionsA. Su executed biological assays, computational studies, data analysis and wrote the manuscript; SW designed and synthesized compounds; A. Sada established biological assay system, prepared and executed biological assay and data analysis; YO, RO and TO planned the project, executed data analysis and wrote the manuscript. LZ and XL synthesized some of the compounds. MS executed computational studies.

Tested compounds, A-1, B-1, B-2, C-1, C-2, C-3, C-4, C-5 and C-6, had been synthesized previously and were used in this work.4,5,9,14)

Biological StudiesExpression and Purification of GST-Fusioned ProteinsGST fusion constructs of MDM2 (amino acids 1–150) and MDMX (amino acids 1–150) were prepared by PCR tagging of the cDNAs with BamHI and XhoI sites at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, and subcloned into pGEX-6P-1 vector (Amersham Pharmacia, Tokyo, Japan). Constructs were expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21-Gold (DE3), Stratagene, CA, U.S.A.) and purified from cell lysates using glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (Amersham Pharmacia, U.S.A.). Purified proteins were further eluted in elution buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 20 mM glutathione).

Biological Activity Assays and Structural–Activity Relationship StudyThe biological activities of synthesized compounds were evaluated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), using GST-tagged MDM2 and MDMX proteins. GST-MDM2 (80 µg/mL in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)) or MDMX (30 µg/mL in PBS) was coated on a 96-well plate (96 Well ELISA Microplate, Half Area, 675061, Greiner) overnight. Subsequently, test compounds (30 or 100 µM in PBS) were added and incubated for 1-hour, followed by addition of p53 (0.4 µg/mL in PBS). After 2-hour incubation, p53 binding to MDM2 or MDMX was detected by using anti-p53 antibody PAb421 (from mouse, monoclonal, Calbiochem) as the 1st antibody and anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG), HRP-linked Whole antibody # NA931V (GE Healthcare, U.S.A.) as the 2nd antibody. The substrate ABT-S was then added together with hydrogen peroxide. Finally, the absorbance at 405 nm of each well was measured with a spectrophotometer, and the inhibitory ratio of each compound was calculated. Nutlin-3, reported by Vassilev et al.,15) was used as a control that inhibits p53–MDM2 binding but do not inhibit p53–MDMX binding.

Shape Similarity ComparisonsThe graphics in Fig. 2 were generated by aligning α-helical 10mer of alanine and either octamer of cAbh-AA or tAbh-AA by ROCS program with default conditions (ROCS 3.2.0.4: OpenEye Scientific Software, Santa Fe, NM, U.S.A. http://www.eyesopen.com).16) The graphics showed the orientation and overlaps with maximum shape similarity values.

Molecular DockingCo-crystal structure (PDB code: 3JZS) of human MDM2, liganded with a 12mer peptide inhibitor (pDIQ) was preprocessed using Protein Preparation Wizard in the Maestro2017-4 suite of programs (Schrödinger, LLC, New York, U.S.A.).17) The embedded ligand (pDIQ) was removed, and the target ligand was docked with Glide program with standard precision (SP) mode,18) and the poses were sorted in order of docking score up to 30 poses. All obtained 26 poses were further structurally refined by molecular dynamics simulations. The ligand–protein bound system was solvated with water (SPC water model) with OPLS3 force field,19) the charge being neutralized by adding 6 Cl− and then buffered with 0.15 M Na+ and Cl−, followed by molecular dynamic simulation of the whole system (NPT ensemble, temperature 300 K, pressure 1.013 bar (=1.0 atm)) for 10 ns with Desmond program.20) The structure at 10 ns, which gave the best MM-GBSA ΔGbind21) value among the 30 poses, was shown in Fig. 6 as a typical docking pose.

We thank Professor Dr. Takatsugu Hirokawa, National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology (AIST) and University of Tsukuba for his help in computational study. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP 26104508 and 16K08157 (YO) and 26293002 and 18H02552 (TO). We also thank OpenEye Scientific (New Mexico, U.S.A.) for the allowance of use ROCS program.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.