2019 年 67 巻 10 号 p. 1144-1151

2019 年 67 巻 10 号 p. 1144-1151

Definitive screening design (DSD) is a new class of small three-level experimental design that is attracting much attention as a technical tool of a quality by design (QbD) approach. The purpose of this study is to examine the usefulness of DSD for QbD through a pharmaceutical study on the preparation of ethenzamide-containing orally disintegrating tablet. Model tablets were prepared by directly compressing the mixture of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and excipients. The five evaluated factors assigned to DSD were: the contents of API (X1) and lubricant (X2), and the compression force (X3) of the tableting process, the mixing time (X4), and the filling ratio of powder in the V-type mixer (X5). After tablet preparation, hardness and disintegration time were measured. The same experiments were performed by using the conventional design of experiments [i.e., L8 and L16 orthogonal array designs and central composite design (CCD)]. Results showed that DSD successfully clarified how various factors contribute to tablet properties. Moreover, the analysis result from DSD agreed well with those from the L8 and L16 experiments. In additional experiments, response surfaces for tablet properties were created by DSD. Compared with the response surfaces created by CCD, DSD could produce reliable response surfaces for its smaller number of experiments. We conclude that DSD is a powerful tool for implementing pharmaceutical studies including the QbD approach.

Pharmaceutical quality by design (QbD) is a modern approach to pharmaceutical development.1,2) Since the QbD concept was introduced in the International Conference on Harmonization Q8 guideline in 2008,3) it has become of central importance to the pharmaceutical industry. According to the QbD concept, quality must be built into the product. The quality of manufactured pharmaceutical products is affected by a large number of formulation variables and manufacturing process parameters. A better understanding of the relationships between factors and characteristics would constitute valuable knowledge for developing desirable pharmaceutical products, and would contribute to a reduction in product variability and defects, thereby enhancing product development, quality, and manufacturing efficiencies. The QbD approach comprises two essential elements, namely screening crucial characteristic factors followed by optimization of the crucial factors to meet the needs of each product. To implement the QbD approach, application of design of experiments (DOE) is strongly recommended.

Two-level orthogonal array designs (e.g., L8 and L16) are cited as a common experimental design for screening crucial factors,4,5) as they enable evaluation of the contribution of characteristic factors with a smaller number of experiments. However, these methods cannot offer information on possible curvature or on the quadratic effects of factors.6) Curvature is the nonlinear effect of a variable and can be evaluated when factors are studied on three or more levels. The center point of a two-level orthogonal array design is customarily added to obtain a global assessment of curvature. However, the quadratic effects of each factor remain to be identified. To deal with this issue, other experimental designs of three or more levels have to be used.

Recently, a new class of three-level experimental design, so-called definitive screening design (DSD), was proposed by Jones and Nachtsheim.7,8) To produce the experimental design, the conference matrix is employed. The conference matrix is composed of fold-over pairs corresponding to each evaluated factor and overall center points. DSD has a great capacity for assessing the main effects of factors and their two-factor interactions without confounding bias. The main effects are always orthogonal to the two-factor interactions. In addition to main effects and two-factor interactions, it enables evaluation of pure-quadratic effects of factors. According to this, we can understand the nonlinear effect of factors on characteristics. DSD is attractive in terms of the small number of experimental runs. Even- and odd-numbered k-factor matrices respectively require 2k + 1 and 2k + 3 experimental runs. These numbers are only about twice that of the evaluated factors. These features allow investigation of a large number of factors in a fairly small experiment, eventually leading to significant reductions in time, resources, and cost during pharmaceutical development. Thus, DSD is attracting considerable attention as a promising technical method for the QbD approach. To date, DSD has been applied to the preparation of a wide range of dosage forms including oral disintegrating films,9) modified-release drug products,10) intranasal gel formulations,11) semisolid dosage forms,12,13) and lyophilized products.14) However, to our knowledge, there is no pharmaceutical study comparing analytical results between DSD and conventional DOE methods. To accumulate enhanced technical knowledge concerning DSD, the present study tested a model of an orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) containing ethenzamide. The model tablets were prepared with different conditions of formulation and process variables assigned by DSD and then the characteristics of hardness and disintegration time (DT) were measured. After analyzing the observed data, the modes of contribution of crucial factors were identified and then response surfaces were created. The same experiments were also performed based on conventional DOE methods. The main conclusion from this study was that DSD is a powerful tool for implementing pharmaceutical studies that adopt a QbD approach.

Ethenzamide and magnesium stearate (MgSt) were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, Japan). SmartEx®(QD50), a coprocessed excipient granule consisting of D-mannitol, low-substituted hydroxypropyl celluloses (L-HPC), and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) for preparing ODTs, was purchased from Shin-Etsu Chemical (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of Model TabletsModel tablets were prepared by the direct tableting method. Ethenzamide, SmartEx® and MgSt were used as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), the excipient for direct compression of ODT, and the lubricant of the model tablet, respectively. In brief, they were dried at 75°C for 24 h and sieved through a 20-mesh screen before tablet preparation. Designated amounts of all components were charged into a V-type mixer with a 500 mL container (VM-2; Tsutsui Scientific Instruments, Tokyo, Japan). In a preliminary experiment, the major components of the model tablet showed similar bulk density: 0.420 and 0.477 g/mL for API and SmartEx®, respectively. The volume of tablet powder was calculated under the assumption that the bulk density values of all components were 0.477 g/mL. After mixing at 45 rpm for a designated period, the resulting tablet powder (200 mg) was compressed into a round tablet using a Handtab 100 hydraulic press. The tablet had a diameter of 8 mm with a 12 mm concave radius of curvature. Experimental designs including DSD, L8, L16, and central composite design (CCD) were designed by the statistical software JMP® 13 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

Measurement of Tablet PropertiesThe tablet properties were evaluated immediately after preparing the model tablets. The hardness of the tablets was determined using a tablet hardness tester (Portable checker PC-30; Okada Seiko, Tokyo, Japan). DT was measured according to the JP17 disintegration test using a disintegration tester (NT-20H; Toyama Sangyo, Osaka, Japan) and water (as solvent) at 37 ± 0.5°C.

Data AnalysisThe experimental data were analyzed with the statistical software JMP® 13 (SAS Institute). Multiple regression analysis applying a least squares assessment was performed to identify the factors considered to be crucial for tablet properties. The multiple regression equations were approximated by a stepwise selection technique. A p-value was set at 0.1 and then selection and retention of variables were repeated until no improvement in overall accuracy was observed from the predicted model. Regarding optimization study, the response surfaces for tablet properties were created by experimental data observed from DSD and CCD experiments, and then their optimal conditions were determined by using satisfaction function.

We investigated the effects of the following variables on tablet properties: the contents of API (X1) and lubricant (X2) in the model tablet; the compression force (X3) of the tableting process; and the mixing time (X4) and the filling ratio of powder in the V-type mixer (X5) (Table 1). We evaluated the DT valuables after converting the observed data into logarithms [log(DT)] to reduce data bias. First, the accuracy of the multiple regression equations constructed by DSD was evaluated. As shown in the scatterplots of experimental versus predicted values (Fig. 1), their coefficients of determination adjusted by the degrees of freedom (adjusted R2) were very high: adjusted R2 for hardness and log(DT) were 0.97 and 0.99, respectively. This indicates that the changes in these tablet properties were well explained by the evaluated factors.

| Run | Factors | Tablet properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | Hardness [N] | Log(DT) | |

| API content [%] | Lubricant content [%] | Compression force [kN] | Mixing time [min] | Filling ratio [%] | |||

| #1 | 30 | 3 | 8 | 60 | 80 | 70.7 ± 3.8 | 2.21 ± 0.01 |

| #2 | 30 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 32.3 ± 3.8 | 1.19 ± 0.02 |

| #3 | 50 | 2 | 4 | 60 | 80 | 29.0 ± 3.6 | 1.72 ± 0.02 |

| #4 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 10 | 40 | 77.0 ± 2.0 | 1.44 ± 0.02 |

| #5 | 50 | 1 | 6 | 10 | 80 | 57.0 ± 3.6 | 1.47 ± 0.03 |

| #6 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 60 | 40 | 53.3 ± 2.1 | 1.55 ± 0.01 |

| #7 | 50 | 3 | 4 | 35 | 40 | 32.3 ± 1.2 | 2.10 ± 0.04 |

| #8 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 35 | 80 | 80.7 ± 3.8 | 1.38 ± 0.05 |

| #9 | 50 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 60 | 71.7 ± 3.1 | 3.09 ± 0.03 |

| #10 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 60 | 60 | 32.7 ± 0.6 | 1.21 ± 0.06 |

| #11 | 50 | 1 | 8 | 60 | 40 | 73.3 ± 1.2 | 1.94 ± 0.02 |

| #12 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 80 | 33.0 ± 2.0 | 1.20 ± 0.00 |

| #13 | 30 | 2 | 6 | 35 | 60 | 57.0 ± 1.0 | 1.54 ± 0.01 |

Each value represents the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) (n = 3).

Hardness (a) and log(DT) (b).

The mode of contribution of the factors to these properties was then assessed. For hardness, X3 showed a remarkable positive effect (p < 0.0001) (Table 2). In addition, negative effects of X1, X2, and X4 were found to be slight but significant (p < 0.05). That is, tablets with higher hardness are assumed to be produced by higher compression force. Moreover, lower contents of API and lubricant and a shorter mixing time had a slight but significant effect on increase in the hardness. For log(DT), X1, X2, and X3 were shown to be significant factors with a strong positive effect (Table 3). As well as the main effect of the factors, the significant interaction between X1 and X4 was verified. Furthermore, quadratic effects of X3 and X5 (i.e., X3*X3 and X5*X5 shown in Table 3) were found; as noted, the capacity to evaluate the quadratic effects of factors is a great advantage of DSD compared with other screening methods such as L8 and L16. The DT of the model tablet tended to be prolonged with increasing contents of API and lubricant and higher compression force.

| Rank | DSD | L8 | L16 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | t-Value | p-Value | Factor | t-Value | p-Value | Factor | t-Value | p-Value | |

| 1 | Compression force (X3) | 37.5 | <0.0001 | Compression force (X3) | 13.98 | <0.0001 | Compression force (X3) | 32.39 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | Lubricant content (X2) | −2.63 | 0.0128 | API content (X1) | −2.86 | 0.0099 | API content (X1) | −5.86 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | API content (X1) | −2.34 | 0.0255 | Lubricant content (X2) | −2.42 | 0.0257 | Lubricant content (X2) | −4.95 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | Mixing time (X4) | −2.1 | 0.0430 | Mixing time (X4) | −2.37 | 0.0285 | X2*X3 | −4.72 | <0.0001 |

| 5 | Mixing time (X4) | −4.16 | 0.0002 | ||||||

| 6 | X1*X3 | −3.48 | 0.0014 | ||||||

| 7 | X1*X2 | −3.03 | 0.0046 | ||||||

| 8 | X2*X4 | 2.63 | 0.0126 | ||||||

| 9 | Filling ratio(X5) | −2.23 | 0.0319 | ||||||

| 10 | X1*X4 | −2.01 | 0.0523 | ||||||

| 11 | X3*X4 | −2.01 | 0.0523 | ||||||

| 12 | X4*X5 | −1.9 | 0.0663 | ||||||

| Rank | DSD | L8 | L16 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | t-Value | p-Value | Factor | t-Value | p-Value | Factor | t-Value | p-Value | |

| 1 | API content (X1) | 32.28 | <0.0001 | API content (X1) | 11.9 | <0.0001 | API content (X1) | 40.62 | <0.0001 |

| 2 | Lubricant content (X2) | 27.19 | <0.0001 | Compression force (X3) | 7.96 | <0.0001 | Compression force (X3) | 26.91 | <0.0001 |

| 3 | Compression force (X3) | 24.18 | <0.0001 | Lubricant content (X2) | 6.32 | <0.0001 | Lubricant content (X2) | 25.5 | <0.0001 |

| 4 | X3*X3 | 15.64 | <0.0001 | X1*X2 | 9.86 | <0.0001 | |||

| 5 | X1*X4 | −10.87 | <0.0001 | X1*X3 | 7.1 | <0.0001 | |||

| 6 | X5*X5 | −9.13 | <0.0001 | Mixing time (X4) | 6.25 | <0.0001 | |||

| 7 | Filling ratio (X5) | −2.27 | 0.0304 | X2*X3 | 3.47 | 0.0015 | |||

| 8 | Mixing time (X4) | 2.22 | 0.0344 | X3*X4 | −3.2 | 0.0030 | |||

| 9 | X2*X5 | −3.15 | 0.0035 | ||||||

| 10 | Filling ratio (X5) | −3.01 | 0.0050 | ||||||

| 11 | X1*X4 | 2.79 | 0.0087 | ||||||

| 12 | X4*X5 | −2.61 | 0.0136 | ||||||

| 13 | X1*X5 | −2.15 | 0.0388 | ||||||

| 14 | X3*X5 | −1.85 | 0.0733 | ||||||

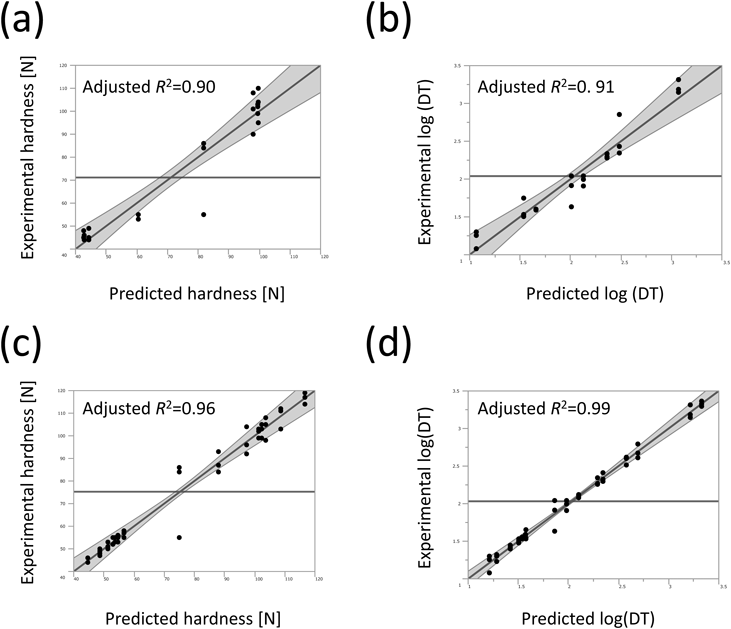

The same screening study was also performed based on conventional L8 and L16 orthogonal array designs (Tables 4, 5). As this screening study evaluated five factors, the L8 experiment was used to examine only main effects, whereas the L16 experiment assessed both the main effects and their interactions. As is the case of the DSD experiment, the scatterplots of experimental versus predicted values for tablet properties were calculated by multiple regression equations (Fig. 2). The models correlated by the L16 experiment appeared to be more reliable than those by the L8 experiment; the L16 experiment showed 0.96 and 0.99 of adjusted R2 for hardness and log (DT); in the L8 experiment, these values were 0.90 and 0.91. Undoubtedly, this is because the L16 orthogonal array design has a larger number of possible explanatory factors to model the properties compared with the L8 design (Tables 2, 3). The multiple regression equations created by the L16 experiment were composed of more than 10 significant factors including main effects and two-factor interactions, whereas those of the L8 experiment explained the changes in hardness and log(DT) by four (X1, X2, X3 and X4) and three significant factors (X1, X2, and X3). Except for the lower reliability of the multiple regression equations from the L8 experiment, the analysis results were similar to each other. Overall, the hardness of the model tablets was predominantly affected by compression force (Table 2). For log(DT), contents of API and lubricant and compression force were significant factors; their ranking of contribution to log(DT) did not change even though the experimental design was changed from L16 to L8 (Table 3). Although the L8 experiment involves the risk of misunderstanding the effects of some factors due to confounding bias, the current dataset appeared to avoid such a risk. We also note that the mode of contribution of the factors obtained from DSD (Tables 2, 3) was consistent with these analytical results, indicating that DSD performed a reliable analysis.

| Run | Factors | Tablet properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | Hardness [N] | Log(DT) | |

| API content [%] | Lubricant content [%] | Compression force [kN] | Mixing time [min] | Filling ratio [%] | |||

| #1 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 80 | 53.7 ± 1.2 | 1.21 ± 0.12 |

| #2 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 60 | 40 | 70.0 ± 7.5 | 1.60 ± 0.01 |

| #3 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 60 | 40 | 46.0 ± 2.6 | 1.59 ± 0.13 |

| #4 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 80 | 101.3 ± 2.1 | 1.98 ± 0.07 |

| #5 | 50 | 1 | 4 | 60 | 80 | 44.7 ± 1.2 | 1.86 ± 0.21 |

| #6 | 50 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 40 | 99.7 ± 9.1 | 2.54 ± 0.27 |

| #7 | 50 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 46.0 ± 1.7 | 2.30 ± 0.03 |

| #8 | 50 | 3 | 8 | 60 | 80 | 75.0 ± 17.3 | 3.22 ± 0.09 |

Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

| Run | Factors | Tablet properties | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 | X5 | Hardness [N] | Log(DT) | |

| API content [%] | Lubricant content [%] | Compression force [kN] | Mixing time [min] | Filling ratio [%] | |||

| #1 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 80 | 53.7 ± 1.2 | 1.21 ± 0.12 |

| #2 | 10 | 1 | 4 | 60 | 40 | 51.3 ± 1.5 | 1.28 ± 0.05 |

| #3 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 40 | 116.7 ± 2.5 | 1.54 ± 0.01 |

| #4 | 10 | 1 | 8 | 60 | 80 | 102.3 ± 3.1 | 1.57 ± 0.02 |

| #5 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 53.0 ± 1.7 | 1.42 ± 0.02 |

| #6 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 60 | 80 | 54.7 ± 1.5 | 1.50 ± 0.03 |

| #7 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 80 | 101.3 ± 2.1 | 1.98 ± 0.07 |

| #8 | 10 | 3 | 8 | 60 | 40 | 103.7 ± 5.1 | 2.10 ± 0.02 |

| #9 | 50 | 1 | 4 | 10 | 40 | 56.7 ± 1.5 | 1.58 ± 0.07 |

| #10 | 50 | 1 | 4 | 60 | 80 | 44.7 ± 1.2 | 1.86 ± 0.21 |

| #11 | 50 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 80 | 108.7 ± 4.9 | 2.34 ± 0.06 |

| #12 | 50 | 1 | 8 | 60 | 40 | 97.3 ± 6.1 | 2.58 ± 0.06 |

| #13 | 50 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 80 | 48.7 ± 1.5 | 2.29 ± 0.05 |

| #14 | 50 | 3 | 4 | 60 | 40 | 48.7 ± 0.6 | 2.69 ± 0.09 |

| #15 | 50 | 3 | 8 | 10 | 40 | 88.0 ± 4.6 | 3.33 ± 0.03 |

| #16 | 50 | 3 | 8 | 60 | 80 | 75.0 ± 17.3 | 3.22 ± 0.09 |

Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). Data #1, #7, #10 and #16 in the L16 orthogonal design are the same as those #1, #4, #5 and #8 in L8 orthogonal design (Table 4).

Hardness (a and c) and log(DT) (b and d).

Considering that the adjusted R2 values of multiple regression equations were very high (Fig. 1), we expected that DSD could provide accurate response surfaces for the tablet properties. We next compared the response surfaces created by DSD to those created by a conventional response surface method, CCD, which is the most popular experimental design for use in response surface methodology. Table 6 shows that X1, X2, and X3 were determined to be crucial factors of CCD judging from the analysis results in Tables 2 and 3. In fact, we considered that the prediction accuracy of the response surfaces from CCD was assumed to be higher than that from DSD because CCD requires a larger number of experiments than DSD; thus, the aim of this experiment was to evaluate whether DSD could produce reliable response surfaces. Figure 3 shows the response surfaces created by DSD and CCD. Overall, both response surfaces created by DSD were roughly consistent with those obtained by CCD. In particular, the response surfaces for hardness closely resembled each other, because the mode of contribution of factors was relatively simple compared with log(DT), and apart from the effect of curvature or quadratic effects, the compression force was by far the most significant factor for hardness. In the case of log(DT), the response surface differed somewhat from that from CCD; for instance, the surface from DSD overemphasized the quadric contribution of the compression force compared with that from CCD. We further conducted a formulation optimization study. A tablet having higher hardness and shorter DT was defined as being preferable. A satisfaction function was used as an indicator to seek the simultaneous optimal preparative conditions.15) To calculate the satisfaction functions, the weights of hardness and log(DT) were fixed at a ratio of 1 : 1. Figure 4 shows the optimal preparative conditions estimated from the response surfaces of DSD and CCD. The optimal conditions were fully consistent with each other. Taken together, although there were indeed slight differences in the response surfaces between DSD and CCD, reliable response surfaces could generally be produced by DSD.

| Run | Factors | Tablet properties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X2 | X3 | Hardness [N] | Log(DT) | |

| API content [%] | Lubricant content [%] | Compression force [kN] | |||

| #1 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 53.3 ± 5.5 | 1.21 ± 0.03 |

| #2 | 15 | 1 | 8 | 99.3 ± 1.5 | 1.65 ± 0.03 |

| #3 | 15 | 3 | 4 | 49.3 ± 1.2 | 1.48 ± 0.03 |

| #4 | 15 | 3 | 8 | 100.0 ± 1.7 | 2.13 ± 0.03 |

| #5 | 45 | 1 | 4 | 50.7 ± 0.6 | 1.48 ± 0.05 |

| #6 | 45 | 1 | 8 | 96.0 ± 5.0 | 2.22 ± 0.03 |

| #7 | 45 | 3 | 4 | 50.3 ± 0.6 | 2.16 ± 0.03 |

| #8 | 45 | 3 | 8 | 86.7 ± 6.7 | 3.00 ± 0.03 |

| #9 | 4.8 | 2 | 6 | 81.0 ± 0.0 | 1.51 ± 0.03 |

| #10 | 55.2 | 2 | 6 | 78.3 ± 1.5 | 2.88 ± 0.08 |

| #11 | 30 | 0.32 | 6 | 82.3 ± 4.0 | 1.38 ± 0.02 |

| #12 | 30 | 3.68 | 6 | 79.0 ± 3.6 | 2.57 ± 0.05 |

| #13 | 30 | 2 | 2.6 | 26.7 ± 0.6 | 1.33 ± 0.02 |

| #14 | 30 | 2 | 9.4 | 109.3 ± 3.1 | 2.37 ± 0.04 |

| #15 | 30 | 2 | 6 | 79.3 ± 6.7 | 1.85 ± 0.02 |

| #16 | 30 | 2 | 6 | 85.7 ± 2.3 | 1.89 ± 0.02 |

Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

Hardness (a and c) and log(DT) (b and d). (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

Blue and red lines correspond with the contour lines of hardness and log(DT) estimated by their multiple regression equations. Higher hardness and shorter DT were regarded as being preferable characteristics in this study. The simultaneous optimal preparative conditions estimated were marked on the contour profiles as circles in pink. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

DSD is a fairly new class of three-level experimental design that is applicable to the QbD approach.7,16) Three levels of factors are assigned to the experimental design according to the conference matrix. As mentioned in the Introduction, the conference matrix is composed of fold-over pairs corresponding to each evaluated factor and overall center points. The number of experimental runs required is almost twice that of evaluated factors, and the number of experiments increases linearly as evaluated factors are added. The main effects are always orthogonal to the two-factor interactions, which means that the main effects estimated by DSD are not biased even if active two-factor interactions are incorporated into the dataset. Unlike DSD, the conventional standard designs such as fractional factorial and Plackett–Burman designs are generally incapable of avoiding potential confounding effects caused by the combination of two-factor interactions and some main effects.12) We believe that DSD can provide a reasonable solution to overcome the problems that might arise in a screening study caused by confounding errors. In addition to main effects and two-factor interactions, DSD allows us to evaluate the quadratic effects of factors. The quadratic effects are always orthogonal to the main factors. This capability enables us to understand the nonlinear effect of factors on characteristics and contributes significantly to creating reliable response surfaces. The number of experiments in DSD is much smaller compared with conventional standard designs for use in response surface methodologies such as CCD and Box–Behnken design. For example, CCD requires at least 15, 25, 27, and 45 experiments to design a 3-, 4-, 5-, and 6-factor matrix, respectively. Regarding the disadvantages of DSD, the accuracy of analysis tends to decrease when the number of active effects is very large. This is because the concept of DSD is established under the sparsity-of-effects principle according to which most of the variation in the response is explained by a relatively small number of effects, regardless of the many factors to be evaluated. In general, for a k factor DSD matrix, if there are k active effects or more that include main effects, two-factor interactions, and quadratic effects, the analysis is likely to be problematic. Furthermore, two-factor interactions are partially confounded with other interactions and pure-quadratic effects.16) Overall, we believe that DSD has a great capacity to accomplish reliable screening and optimization studies in a single step with a small number of experiments.

To date, a number of studies have applied DSD to their formulations. The dosage forms that have been investigated are reported to be oral disintegrating films,9) cross-linked chitosan disc-modified drug release,10) intranasal transferosomal mucoadhesive gel formulation,11) and ointment formulation.12) In addition to these, van Heugten and Vromans introduced DSD to scale up a study of semisolid dosage forms to understand the manufacturing processes using a QbD approach.13) Goldman et al. used DSD for optimization of a manufacturing process involving lyophilization for the manufacturing of monoclonal antibody drug products.14) The authors created response surfaces for the characteristics of primary drying time and primary drying product temperature, and established a design space of lyophilization process parameters to satisfy the criteria.14) As well as in the pharmaceutical research field, DSD has also been used for the optimization of analytical parameters of mass spectrometry.17,18)

However, a sizeable body of work on DSD, to our knowledge, no pharmaceutical study has compared DSD with conventional DOE methods. Consequently, we compared the analytical results observed from DSD with those from common DOE methods including L8 and L16 orthogonal array designs and CCD. We succeeded in characterizing the relative ability of DSD for use in pharmaceutical studies, and therefore our study offers valuable knowledge concerning DSD. As well as having sufficient capacity to screen crucial factors, we confirmed that DSD was able to create reliable response surfaces for tablet characteristics. DSD could therefore be a promising tool for pharmaceutical studies adopting a QbD approach.

The present study provides enhanced technical knowledge concerning DSD for use in pharmaceutical studies. DSD could construct accurate multiple regression equations between factors and tablet properties, and the effects of the evaluated factors were fully elucidated. As well as main effects, DSD found significant quadratic effects. Furthermore, the analysis results obtained from DSD were consistent with those from conventional methods (L8 and L16 orthogonal array designs). In addition, response surfaces for tablet properties were created by DSD, and then the optimal preparative condition for a desirable tablet were estimated. The optimal condition was consistent with that estimated from the conventional response surface method (CCD). Therefore, it was confirmed that DSD could produce relatively reliable response surfaces, even though the number of experiments was much smaller than for CCD. From these findings, the present study successfully characterized the usefulness of DSD for pharmaceutical studies.

The authors thank Mr. Naohiro Masukawa, SAS Institute Japan Ltd. for his solid technical support.

The authors declare that they have no financial or competing interests concerning this manuscript. The Department of Pharmaceutical Technology, University of Toyama is an endowed department, supported by an unrestricted Grant from Nichi-Iko Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Toyama, Japan).