2019 年 67 巻 6 号 p. 576-579

2019 年 67 巻 6 号 p. 576-579

Spatiotemporally controllable nitric oxide (NO) releasers are very attractive chemical tools for investigating the biological activities of NO, which is involved in the regulation of vasodilation, neurotransmission, and immune responses. We previously developed an easily synthesized, yellowish-green-light-controllable NO releaser, NO-Rosa5, and characterized its photoredox reaction mechanism. Here, we aimed to establish the biological applicability of NO-Rosa5 for in cellullo and ex vivo experiments. We successfully demonstrated yellowish-green-light-controlled NO release in HEK293T cells in vitro, as well as photomanipulation of the rat aorta response to NO in an ex vivo system. Furthermore, NO-Rosa5 showed lower toxicity than NOBL-1, a previously reported blue-light-controllable NO releaser, as determined by tetrazolium salt cell viability assay. Overall, our results indicate that NO-Rosa5 is a biocompatible, photocontrollable NO releaser with low toxicity and potentially broad applicability.

Nitric oxide (NO) is synthesized in the human body by nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and is involved in the regulation of various physiological processes, serving as an endothelial-derived relaxing factor (EDRF), a neurotransmitter, and an immune response mediator.1–4) It is a colorless gas that is unstable under physiological conditions (t1/2 = 0.1–5 s); consequently NO releasers, which can store and release NO, have been developed for biological research on the roles of NO or as candidate chemotherapeutic agents.5) Among them, light-controllable NO releasers are expected to be particularly useful as precisely controllable chemical tools or as agents for blood pressure regulation.6–11) So far, several transition metal-nitrosyl complexes, which contain low-energy metal-nitrosyl bonds as visible light-absorbing chromophores, have been developed as visible-light-controllable NO releasers. However, transition metal complex often shows problematic cytotoxicity after ligand release.12) Non-metal-containing photoresponsive NO releasers have also been developed, but these generally require relatively cytotoxic UV light as a one-photon light source for NO release. Although near-IR two-photon excitation methods have been explored to trigger NO release in order to overcome the disadvantages of UV light, the necessary devices are expensive and not readily available.10,13) To overcome these drawbacks, some groups have developed visible-light- or near-IR-light-controllable NO releasers.14,15) Our group has developed light-controllable NO releasers that are triggered by photoinduced electron transfer (Fig. 1, PeT-driven NO releasers).16–18) These PeT-driven NO releasers are composed of two moieties; an NO-releasing moiety (N-nitrosoaminophenol structure) and a light-harvesting antenna moiety. Upon excitation of the antenna moiety in these compounds, photoinduced electron transfer from the NO-releasing moiety to the antenna moiety takes place to form an unstable phenoxyl radical. This radical homolytically releases NO to afford a stable quinoneimine product. Based on this mechanism, we developed a blue-light-controllable NO releaser, NOBL-1, and yellowish-green-light-controllable one, NO-Rosa1.17) In the previous paper, we showed that the proximity between the NO-releasing moiety and the antenna moiety was the most critical factor determining the NO-releasing efficiency; as a result, we found that NO-Rosa5, which was readily synthesizable, showed the most efficient NO release among various NO-Rosa derivatives, based on photoredox parameter analysis. Our strategy is more flexible than that of other groups to develop highly functionalized NO releasers (for example, double-lock NO releasers activated by enzymatic and photochemical reaction).18) In the present work, we examined whether NO-Rosa5 is available for biological experiments. We confirmed that NO release in HEK293T cells by NO-Rosa5 was controllable with a yellowish-green light source. In addition, photomanipulation of vasodilation was achieved ex vivo under a Magnus test condition. Furthermore, NO-Rosa5 at a sufficient concentration to induce vasodilation ex vivo did not show strong toxicity. Thus, our results indicate that NO-Rosa5 should be an excellent chemical tool for NO-related research.

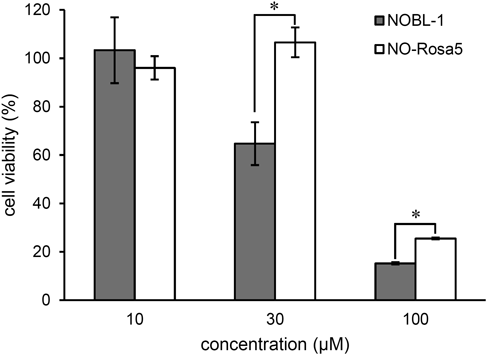

We compared the cellular toxicity of NO-Rosa5 with that of NOBL-1, a previously reported blue-light-controllable NO releaser (Fig. 1). After incubation of HEK293T cells in a 96-well plate overnight (5000 cells/well), the cells were treated with NOBL-1 or NO-Rosa5 at various concentrations for 2 d. Then, the cells were treated with a water-soluble tetrazolium salt, WST-8 (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan), and the absorbance was measured with a plate reader. Neither compound was cytotoxic at 10 µM, as shown in Fig. 2, but NOBL-1 showed greater toxicity to HEK293T cells at 30 µM than did NO-Rosa5. Although, at 100 µM, both compounds induced cell death, NO-Rosa5 was less toxic. The difference in their cytotoxicity might be due to the structural difference in the NO-releasing moiety: NOBL-1 has a carboxy group close to the phenolic hydroxy group, and the carboxylate anion might react as a pendant base and induce oxidation of phenol.19) This in turn might result in the generation of reactive oxygen species, which could induce cell death.

After incubation of HEK293T cells with NOBL-1 or NO-Rosa5 for 48 h, cell viability was measured using WST-8. The results are mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) * p < 0.01 when compared by Student’s t-test (n = 3).

In the previous study, we found that blue light irradiation (470–500 nm), used to excite NOBL-1, is more cytotoxic than yellowish-green light (530–590 nm), used to excite NO-Rosa5.17) Thus, overall, NO-Rosa5 appears to be more suitable for biological applications than NOBL-1.

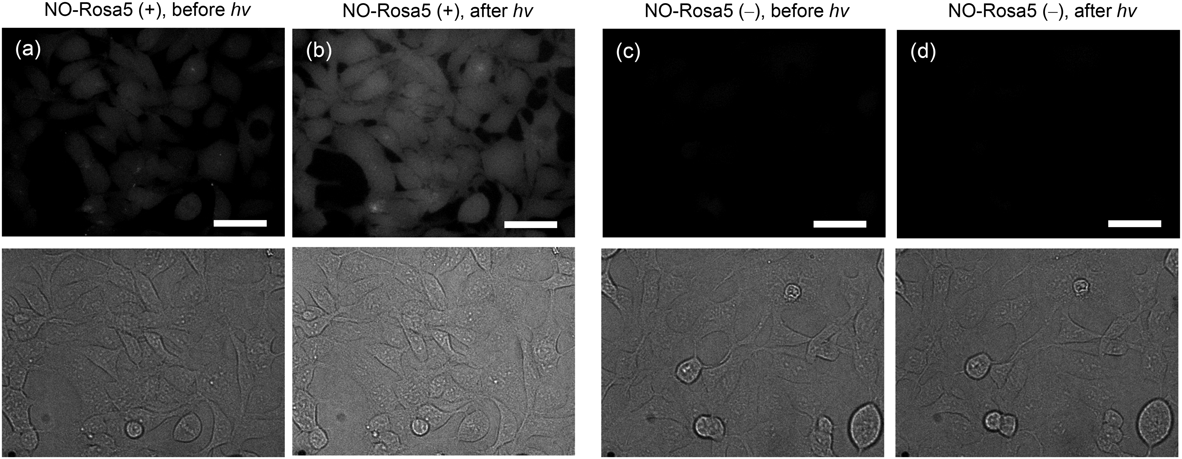

To examine the applicability of NO-Rosa5 for cellular experiments, we conducted fluorescence imaging to monitor NO release from NO-Rosa5 in cells. NO release in cells was monitored with a green-fluorescent NO probe, diaminofluorescein-FM diacetate (DAF-FM DA) because the fluorescence wavelength might not overlap between DAF-FM and NO-Rosa5.20) After incubation of HEK293T cells with DAF-FM DA (10 µM), the cells were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (D-PBS), then NO-Rosa5 (10 µM) was added, and the cells were irradiated with a MAX303 (Asahi Spectra) equipped with a 530–590 nm band-pass filter. As shown in Fig. 3, a fluorescence increment was observed in the presence of NO-Rosa5, while the fluorescence was not increased in the absence of NO-Rosa5 or light irradiation. Thus, controlled NO release in cells was successfully achieved with the low-toxicity combination of NO-Rosa5 and a yellowish-green light source. Probably, NO-Rosa5 would localize to mitochondria in living cells due to its cationic charge so that NO-Rosa5 might be utilized as a mitochondria-targeting NO releaser.21)

Fluorescence imaging of NO release from NO-Rosa5 in HEK293T cells was performed by using DAF-FM DA. Cultured HEK293T cells were treated with DAF-FM DA (10 µM) and either NO-Rosa5 (10 µM) or vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)). The dishes were then photoirradiated with yellowish green light (530–590 nm, 146 mW/cm2 for 15 min), and cells were observed with a confocal microscope to obtain DIC images and fluorescence images. (a) Before photoirradiation with NO-Rosa5, (b) after photoirradiation with NO-Rosa5, (c) before photoirradiation without NO-Rosa5, (d) after photoirradiation without NO-Rosa5. Upper: Fluorescence images; Lower: DIC images. The scale bar represents 40 µm.

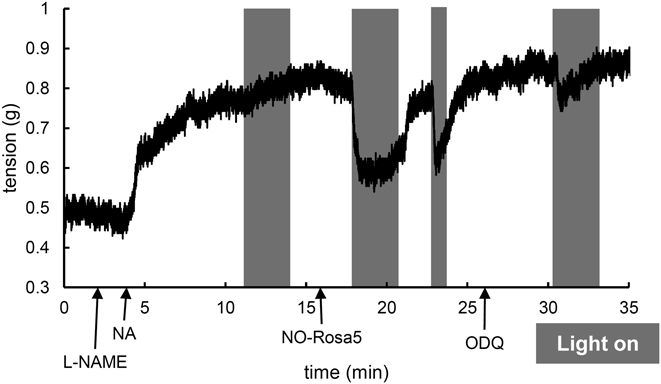

To further evaluate the biological applicability of NO-Rosa5, we examined photocontrol of vasodilation, one of the most important physiological activities of NO. Under physiological conditions, NO from endothelial cells can activate soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC) to accelerate production of guanosine 5′-cyclic monophosphate (cGMP), which induces vasodilation in vascular smooth muscle. For ex vivo vasodilation, a rat aorta strip was placed in a Magnus tube filled with Krebs buffer. To block endogenous NO generation, L-nitroarginine methyl ester (L-NAME), an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, was administered before precontraction of the strip with noradrenaline (NA). When the aorta was irradiated with yellowish-green light (530–590 nm) in the absence of NO-Rosa5, vasodilation did not occur, while in the presence of NO-Rosa5, yellowish-green light irradiation induced vasodilation. This vasodilation was reversible and irradiation-dependent. Further, the reproducibility of the photocontrollable vasodilation was confirmed by conducting irradiation again. To examine whether NO-Rosa5 activated the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway, a sGC inhibitor, 1H-1,2,4-oxadiazolo[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one (ODQ), was administered.22) Treatment with ODQ for a few minutes clearly inhibited the photo-triggered vasodilation. These results indicate that the combination of NO-Rosa5 and yellowish-green light could control NO release-mediated activation of the NO-sGC-cGMP pathway, a physiological activity of NO, under ex vivo conditions.

In conclusion, we investigated the suitability of NO-Rosa5 for biological experiments. In terms of the toxicity of the compound itself and the release-inducing light, NO-Rosa5 was a superior NO releaser to NOBL-1. Furthermore, NO-Rosa5 was confirmed to be applicable for in cellulo and ex vivo use to control NO activity. Thus, NO-Rosa5 is expected to be a useful chemical tool for NO research.

NOBL-1 and NO-Rosa5 were synthesized based on previous reports.16,18) All other reagents and solvents were purchased from Aldrich, FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan), or Dojindo, and were used without purification.

Cell Viability AssayCell viability was assessed using water-soluble tetrazolium WST-8 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Dojindo). HEK293T cells were seeded at a concentration of 5 × 103 cells per well on a 96-well plate. After 24 h, cells were treated with the indicated compounds for 48 h. The WST-8 reagent was added and cells were incubated at 37°C for 3 h in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The absorbance at 450 nm of the medium was measured.

Fluorescence Imaging of NO Release in HEK293T CellsHEK293T cells were plated on 3.5 cm glass bottom dishes (Matsunami, #D1131H) at 2.0 × 105 cells/dish with 2 mL of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing Mg2+ and Ca2+ (DMEM). The cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% (v/v) CO2 in air for 2 d, then washed with D-PBS (2 mL × 3), and incubated with 10 µM DAF-FM DA (DMSO 0.2%) for 30 min under the above conditions. The cells were washed with D-PBS (2 mL × 3), and treated with 10 µM NO-Rosa5 (DMSO 0.1%) for 30 min under the above conditions. The cells were irradiated with a MAX-303 (530–590 nm, 146 mW/cm2) for 15 min. Before and after irradiation, the cells were examined under a confocal fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX71).

Modulation of Vasodilation by NO-Rosa5 under Yellowish-Green Light IrradiationA rat aortic strip was placed in a Magnus tube filled with Krebs buffer (10 mL) at 37°C. The tension was recorded on a LabChart 7 (ADInstruments). To the magnus tube was added a solution of 100 mM L-NAME in DMSO (10 µL) before addition of a solution of 10 mM noradrenaline (10 µL). After equilibration, a solution of 10 mM NO-Rosa5 in DMSO (10 µL) was added, and the tube was irradiated with a MAX-303 (70 mW/cm2). After examining the effect of repeated irradiation (see Fig. 4), to the tube was added a solution of 10 mM ODQ (10 µL) to inhibit sGC.

A rat aortic strip was placed in a Magnus tube filled with Krebs buffer at 37°C. The strip was pretreated with L-NAME (100 µM) and noradrenaline (NA, 10 µM). After equilibration, NO-Rosa5 (10 µM) was added to the tube. ODQ (10 µM) was treated to inhibit sGC. The strip was irradiated with a light source (MAX-302, Asahi Spectra) equipped with a 530–590 nm band-pass filter (70 mW/cm2).

This animal experiment was performed in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Science and International Affairs Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT). The study design was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Nagoya City University (No. H25-P-09).

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H05103 (H.N.), 18K16742 (Y.H.), 18K14873 (N.I.) as well as by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from MEXT (26111012, H.N.).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.