2019 年 67 巻 6 号 p. 505-518

2019 年 67 巻 6 号 p. 505-518

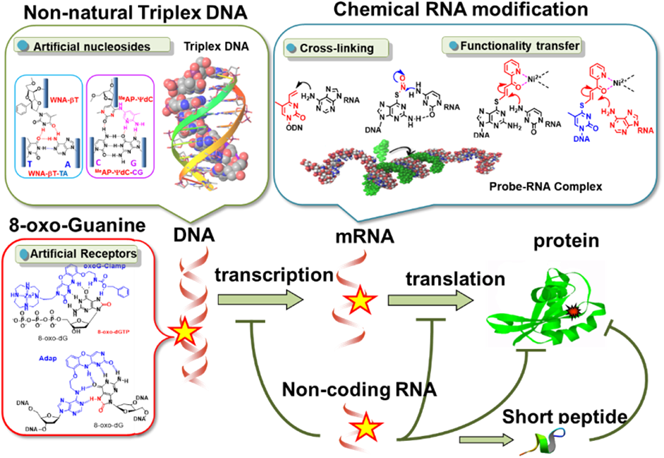

Nucleic acid therapeutics such as antisense and small interfering RNA (siRNA) have attracted increasing attention as innovative medicines that interfere with and/or modify gene expression systems. We have developed new functional oligonucleotides that can target DNA and RNA with high efficiency and selectivity. This review summarizes our achievements, including (1) the formation of non-natural triplex DNA for sequence-specific inhibition of transcription; (2) artificial receptor molecules for 8-oxidized-guanosine nucleosides; and (3) reactive oligonucleotides with a cross-linking agent or a functionality-transfer nucleoside for RNA pinpoint modification.

In our approach to genome-targeting chemistry, we have focused on the development of recognition molecules able to discriminate single nucleotide differences in DNA and RNA molecules. Regardless of genetic or epigenetic origin, chemical species react with nucleotides, resulting in a significant impact on genetic function by altering recognition characteristics or by causing mutations. A single nucleotide mutation (a point mutation) is the most frequently found gene disorder, and plays an important role in disease pathogenesis. Therefore, the development of an oligonucleotide capable of discriminating single nucleotide differences in DNA or RNA for diagnostic and therapeutic purposes is desired. To approach this goal, our laboratory has conducted the following three projects, which will be summarized in this review: (1) an RNA-targeting reaction with cross-linking or functionality-transfer oligonucleotides; (2) the formation of non-natural triplex DNA for sequence-specific inhibition of transcription by newly designed non-natural nucleotides; and (3) the recognition of 8-oxidized-guanosine derivatives by artificial receptor molecules (Fig. 1).

(Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

More than 100 modified nucleosides have been found in ribosomal RNA (rRNA), tRNA, small nuclear RNA (snRNA) and small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), including pseudouridines, 2′-O-methylations, the 5-methylation of cytosine, the deamination of adenine and cytosine, N1 or N6 of adenine, and N2 or N7 of guanine, as well as hyper-modification of nucleosides. Recently, modifications in the internal region of mRNA have been found to play potential roles in gene regulation. In the meantime, chemical damage to RNA by UV-irradiation, oxidation, alkylation, and chemical deamination can alter the function of RNA. These biological bases led us to design chemical tools that can efficiently modify nucleotides in RNA in a highly specific manner.

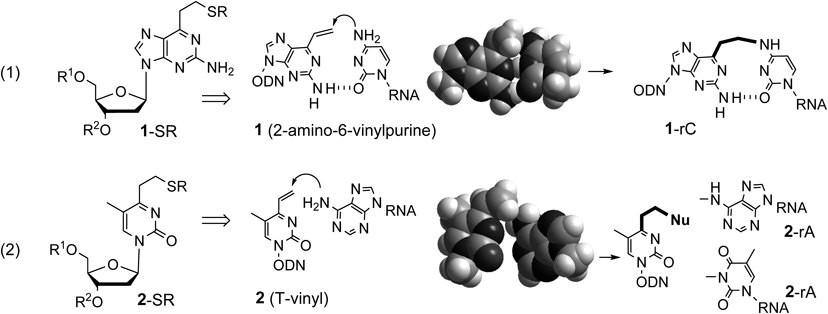

2.1. Cross-Linking OligonucleotidesThis project was initiated by designing cross-linking nucleosides. The cross-linking unit in oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) needs to remain stable until it accesses the target site. To realize this requirement, the reactivity of the unit must be induced by hybridization with the target RNA. The validity of this strategy was first demonstrated by a 2-amino-6-vinylpurine derivative (1). The sulfide-protected vinyl group of 1 (1-SR) in ODN regenerates the vinyl group in the duplex to exhibit selective cross-linking to cytosine bases1–6) (Fig. 2-1). This design concept has been expanded to the inducible cross-linking 2 (T-vinyl) for adenine (Fig. 2-2). The vinyl group of 2 was expected to react with a 6-amino group of adenine in the Watson–Crick face.

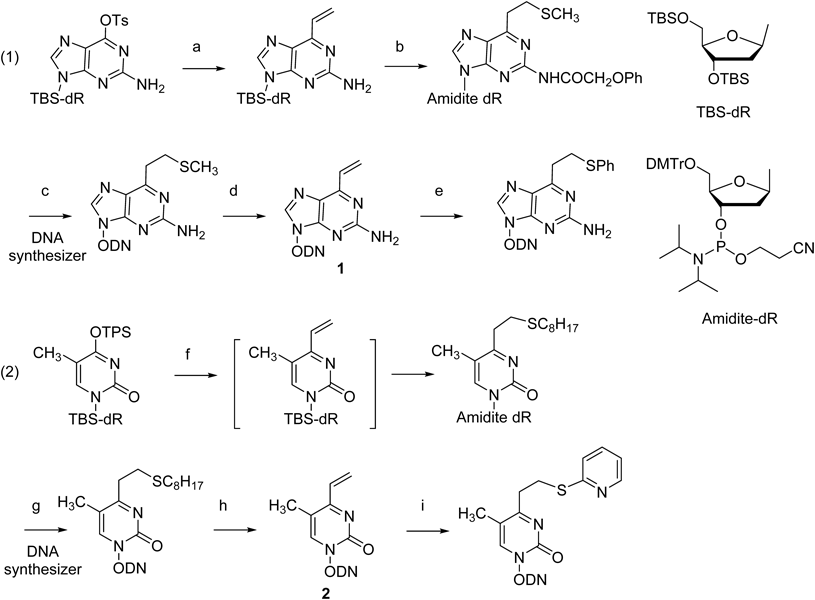

2-Amino-6-vinylpurine (1) was synthesized from a 6-O-(p-toluenesulfonyl)-2′-deoxyguanosine derivative by a Pd(PPh3)4-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction using a vinylboronic anhydride pyridine complex. The methylsulfide-protected 2-amino-6-vinylpurine was incorporated into the ODN by an automated DNA synthesizer, and its vinyl group was regenerated by oxidation with magnesium metaperoxyphthalate (MMPP) and successive treatments under an alkaline condition. A variety of thiol compounds were conjugated to the vinyl group (Chart 1-1). T-Vinyl was synthesized in a similar manner using a 4-O-triisopropylbenzenesulfonyl derivative of thymidine. As the 2 monomer was unstable, it was obtained only in its protected form with octane thiol (2-SOct), which was incorporated into the ODN by standard amidite chemistry (Chart 1-2).

(a) nBu3SnCH = CH2, Pd(PPh3)4, dioxane; (b) (1) MeSNa, CH3CN, (2) PhOCH2COCl, 1-HBT, Pyridine, CH3CN, (3) TBAF, THF, (4) DMTrCl, thioanisole, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, (5) 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (c) (1) Automated DNA synthesizer, (2) 0.1 M NaOH, (3) 10% AcOH; (d) (1) 3.0 eq MMPP, pH 10, (2) 0.47 M NaOH; (e) Ph-SH; (f) (1) 2,4,6-trivinylcyclotriboroxane pyridine complex, Pd(PPh3)4, LiBr, K2CO3, H2O : 1,4-dioxane = 1 : 3 solution, then C8H17SH, CH3CN; (2) TBAF, THF; (3) DMTrCl, thioanisole, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (4) 2-cyanoethyl N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (g) (1) DNA/RNA synthesizer, (2) K2CO3 in dry methanol in the presence of octanethiol, (3) 5% aqueous AcOH, (h) (1) magnesium metaperoxyphthalate (MMPP) carbonate buffer, (2) 0.5 M NaOH; (i) 2-mercaptopyridine.

Intracellular application was demonstrated by the polyethylene glycol (PEG) conjugate of the oligodeoxynucleotide incorporating 1-SPh, which was mixed with poly-L-lysine to form polyion complex micelles. This PEG-ODN-1-SPh conjugate exhibited higher inhibition activity compared to the conjugate with the corresponding natural oligodeoxynucleotide alone7) (Fig. 3).

The cross-linking reaction of the T-vinyl-ODN proceeded rapidly and selectively to the substrate RNA having a uridine at the complementary positions8) (Fig. 4). It was revealed by detailed investigation that the cross-link was formed mainly with the adjacent adenine residue at the 5′ position relative to U.

T-Vinyl in the homopyrimidine ODN selectively formed a cross-link for the adenine base of the AT base pair at the target site in the homopurine strand of the duplex (Fig. 5). The T-vinyl was also applied to cross-linking in the four-stranded DNA helices (i-motif), in which two parallel duplexes were complexed in an antiparallel fashion by alternatively intercalating hemiprotonated cytosine–cytosine base pairs. As the i-motif is folded at acidic pH due to protonation of the cytosines, the 2-thiopyridine sulfide protected T-vinyl (2-SPy) was activated under slightly acidic conditions. T-Vinyl (2-SPy) incorporated at the 5-terminal of C-rich ODN formed a cross-link with the adenine base in the loop region9) (Fig. 5). The cross-link succeeded in stabilizing the i-motif four-stranded structure at nearly neutral pH.

The strategy to induce site- and base selective modification of RNA relies on the functionality-transfer reaction, in which the proximity effect between the reactive unit of the ODN and the target base of RNA promotes the transfer reaction10,11) (Fig. 6).

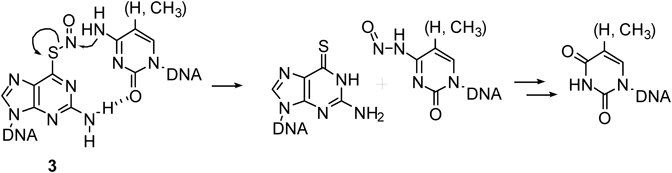

In the first example, a nitrosyl transfer reaction was demonstrated using an ODN containing S-nitrosy-2′-deoxy-6-thioguanosine (3). The nucleophilic attack of the 4-amino group of the cytosine base to the nitrosyl group caused the nitric oxide (NO) transfer to the 4-amino group of the cytosine base12) (Fig. 7). The nitrosyl group transfer took place only for the cytosine, with high site-selectivity. The 5-methylcytosine base was converted to a thymine base by the NO-transfer reaction following a slightly acidic treatment, illustrating a chemical editing reaction. Unfortunately, this deamination reaction was not observed in the cell experiments, probably due to the instability of the S-NO structure. Therefore, we next tried to develop a new functionality transfer reaction to allow for the more stable chemical modification of RNA.

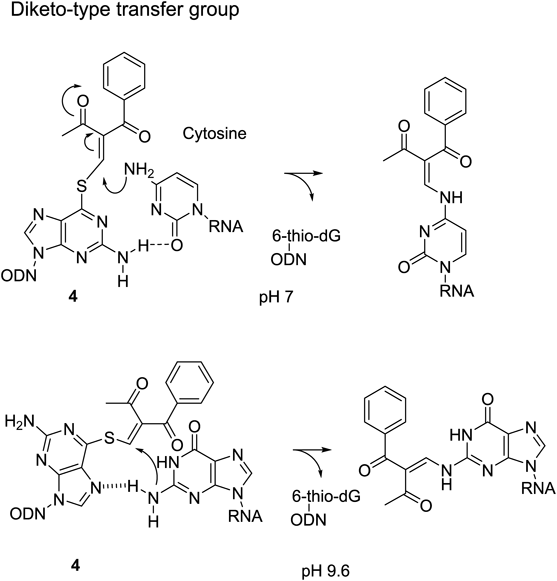

The 2-vinyliden-1,3-diketo unit was next attached to 6-thio-dG (4), which was transferred to the 4-amino group of the cytosine base through a Michael addition, followed by β-elimination of 6-thio-dG, which lead to the transfer product13) (Fig. 8). The cytosine-selective transfer reaction was confirmed; however, unexpectedly, the transfer to the guanine base was greatly enhanced under the alkaline condition. This interesting phenomena was interpreted to be due to the contribution of the enolate form of the guanine base.14) Accordingly, NiCl2 was used to lower the pKa value of H-N1, thereby allowing the transfer reaction to the guanine base to take place under a neutral condition.15) This more efficient guanine modification was applied to the site-specific labelling of RNA16) and O6-methyl guanosine-containing DNA.17)

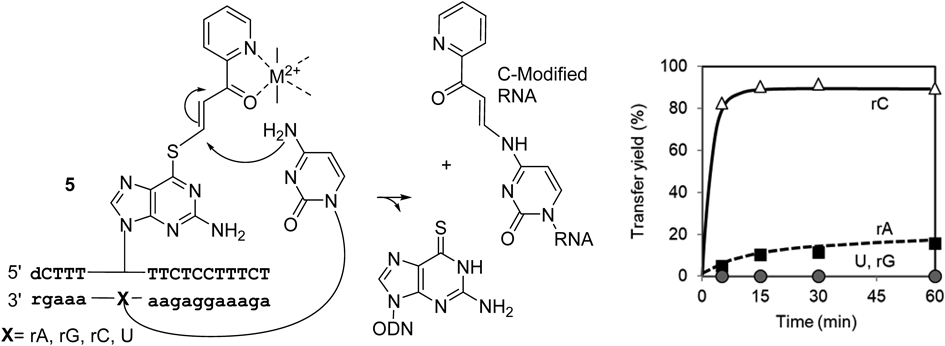

Next, a pyridinyl-keto vinyl group (5) was designed to attain inducible reactivity. First, the pyridinyl-keto part was expected to form a complex with a divalent metal cation to enhance the reactivity for nucleophiles by an electron-withdrawing effect18) (Fig. 9). The use of the (E)-2-iodovinylpyridinylketone unit is essential for the transfer reaction, because the (Z)-isomer did not promote the reaction at all.

The transfer reaction was very selective for the cytidine target, producing approximately 90% yield after 10 min at 37°C and pH 7 in the presence of NiCl2. Rate acceleration was estimated to be more than 200-fold compared with the previous system involving the diketo transfer group. The (E)-pyridinyl keto transfer group was introduced to 2′-deoxy-4-thiothymidine (4-thioT) for an adenine selective transfer reaction. The transfer reaction proceeded efficiently and specifically to the 6-amino group of the target adenosine in RNA, exhibiting about 90% completion after 10 min. In this case, CuCl2 was more effective than NiCl219) (Fig. 10).

Detailed experiments revealed that NiCl2 induced the formation of a bridging complex between the pyridine keto unit and 7N of the purine base of the target RNA to enhance the proximity effect between the amino group and the vinyl group (Fig. 11). This conclusion illustrates an advantage of the pyridinyl keto transfer group in terms of high stability together with inducible reactivity.

The formation of stable triplex DNA is a unique strategy to recognize the duplex DNA sequence, and as such has great potential in the development of gene targeting technology for the regulation of gene expression, diagnostics and sequencing technologies.20–23) Triplex DNA is formed in the major groove of duplex DNA, and is classified into two types according to the binding direction of the triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) against the duplex DNA. A purine-rich TFO adopts an anti-parallel orientation to bind with the homopurine strand of a duplex DNA via two reverse Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds (Fig. 12, G-GC, A-AT or T-AT triplets), whereas pyridimidine-rich TFO binds with the homopurine strand via two Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds in a parallel orientation24–27) (Fig. 12, C+-GC and T-AT triplets). Accordingly, regardless of the anti-parallel or parallel orientation, the formation of stable triplex DNA is limited to the homopurine-homopyrimidine DNA region, and insertion of C or T in the homopurine strand can interrupt this triplex DNA formation (Fig. 12-C). To form triplex DNA at the region where the homopurine-homopyrimidine stretch is discontinued, a wide variety of nucleosides have been designed for this inversion site recognition in the case of both parallel type28–32) and anti-parallel type triplex formations.33–35) We have focused on the development of non-natural nucleoside analogs for the formation of the stable triplex DNA in an antiparallel mode.

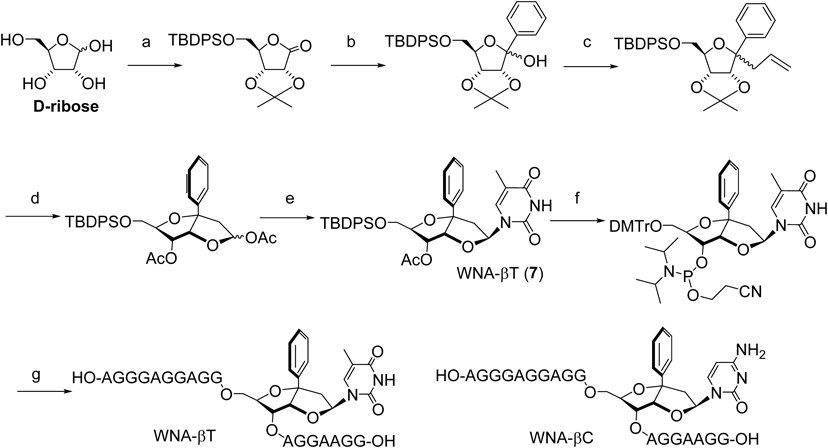

Figure 13 explains the design of WNA-βT (7).36) An ethylene spacer with C1′ α-stereochemistry brings the thymine for hydrogen bonds to the adenine (A). Conformation of the ethylene spacer is fixed in a 5-membered ring (B). A benzene ring at the C1′ position is introduced for stacking and/or van der Waals interactions (C). The benzene ring and the thymine base are aligned in a W-shape, thus this molecule has been named a W-shaped nucleoside (WNA). WNA-βT and βC indicate either a thymine base or cytosine base with the β-configuration, respectively. WNA derivatives were synthesized starting with D-ribose37) (Chart 2). The key intermediate was subjected to N-glycosidation, and the β-isomer was isolated, then transferred to the corresponding amidite precursor, followed by incorporation into the TFOs by an automated DNA synthesizer.

(a) (1) acetone, H+, 2) TBDPSCl, TEA, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 3) PCC, CH2Cl2; (b) (1) PhLi, THF; (c) allyltrimethylsilane, ZnBr2, CH3NO2; d) 1) OsO4, NaIO4, pyridine, 2) 5% H2SO4, THF, 3) Ac2O, pyridine, e) thymine, HMDS, TMSCl, SnCl4, CH3CN, f) (1) nBu4NF, THF, (2) aqueous NaOH, MeOH, (3) DMTrCl, pyridine, (4) iPr2NP(Cl)OCH2CH2CN, iPr2NEt, CH2Cl2; (g) (1) Automated DNA synthesizer, (2) 0.1 M NaOH, (3) 10% AcOH.

Triplex formation was evaluated by gel shift assay with non-denatured polyacrylamide gel, and the bands were quantified to afford the equilibrium association constant. Among a number of WNA analogs, WNA-βT exhibited a selective stabilizing effect for the TA inversion site, whereas WNA-βC showed high selectivity to a CG site. Interestingly, the triplex with a WNA-βT/TA and WNA-βC/CG combination showed higher stability than either of the natural type triplexes (Table 1). However, subsequent studies have shown that the recognition selectivity of WNA-βT and WNA-βC is dependent upon neighboring sequence context.38,39) Substitution at the benzene unit of WNA-βT was able to partially solve the problem of sequence dependency.40–46)

| Z | XY | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TA | AT | CG | GC | |

| dG | 0.004 | 0.008 | 0.008 | 0.086 |

| dA | <0.001 | 0.074 | <0.001 | 0.047 |

| WNA-βT | 0.300 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.082 |

| WNA-βC | <0.001 | 0.025 | 0.115 | 0.047 |

TFO: 3′-GGAAGG AZG GAGGAGGGA-32P-5′; 5′-GGGAGGGAGGGAAGG AXG GAGGAGGGAAGC-3′; 3′-CCCTCCCTCCCTTCC TYC CTCCTCCCTTCG-5′.

To demonstrate the utility of WNA-βT for the antigene inhibition of gene expression, the WNA- βT was incorporated into amino-modified TFOs containing the promoter region of the Bcl2 and the survivin gene.47) Bcl2 and survivin gene products are inhibitors of apoptosis and are overexpressed in a variety of tumors.48) The modified TFOs targeting Bcl2 and survivin exhibited an antitumor effect for A549 cells with higher potency compared with those TFOs composed of only natural nucleotides or with a scrambled sequence (Fig. 14).

Bcl2 natural: 5′-G TGG TGGUGGUUGUGGGGTG-amino 3′; Bcl2 WNA-βT: 5′-GβTGGβTGGUGGUUGUGGGGβTG-amino-3′; Survivin natural: 5′-GGUUGUUGGUGGGUGTGUUGUG-amino-3′; Survivin WNA-βT: 5′-GGUUGUUGGUGGGUGβTGUUGUG-amino-3′; Scrambled: 5′-UUGTGGUGGGUGGUGGUGUGUU-amino-3′.

Despite the successful recognition of a TA inversion site by WNA-βT, recognition of a CG inversion site was not achieved. The canonical T/CG base complex, which contains a single hydrogen bond between the thymine and cytosine bases, was taken as the basis of a new design.49,50) A 2,5-diamino-3-methylpyridine unit (MeAP) was first attempted in order to conjugate isocytidine (isodC) as an additional binding unit for the remote guanine base.51,52) However, as the isodC derivative was unstable, a methylpyridine unit was introduced to the pseudocytosine base (ΨdC)53–55) (Fig. 15). The 3-methyl group was thought to enhance the pKa value of the pyridine unit. Finally, the 2-amino-3-methylpyridine derivative of the pseudocytidine (MeAP-ΨdC, 8) was shown to have superior recognition property.

The synthesis of MeAP-ΨdC (8) was started with pseudothymidine and transformed into the amidite precursor, which was then incorporated into the TFO by standard amidite chemistry (Chart 3). The triplex stability of TFOs incorporating T at position Z is summarized in Table 2. TFOs incorporating MeAP-ΨdC formed a stable triplex against duplex DNAs, including a CG target base pair, regardless of the flanking bases, with an affinity comparable to the canonical T/AT base triplet. Importantly, MeAP-ΨdC showed selective CG base pair recognition regardless of the sequence context. The pKa value of MeAP-ΨdC was determined to be 6.3, suggesting that the protonated 2-aminopyridine unit may interact with the guanine base by hydrogen bonding, as expected.

(a) (1) DMTrCl, pyridine, (2) TBSCl, imidazole, DMF; (b) 3-nitro-1,2,4-triazole, diphenyl chlorophosphate, TEA, CH3CN, (c) 2,5-diamino-3-methylpiridine, DBU, CH3CN; (d) (1) phenoxyacetic anhydride, pyridine, (2) 3HF-TEA, THF, (3) 2-cyanoethyl-N,N-diisopropylchlorophosphoramidite, DIPEA, CH2Cl2; (e) (1) Automated DNA synthesizer, (2) 0.1 M NaOH, (3) 10% AcOH.

| 3′NZN′5′ | Z | Ks (106 M−1) for XY | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC | CG | AT | TA | ||

| 3′GZA5′ | T | 5.0 | 11.2 | 31.2 | 4.1 |

| MeAP-ΨdC | 1.8 | 32.6 | n.d. | n.d. | |

| 3′GZG5′ | T | 5.2 | 6.2 | 10.9 | 4.7 |

| MeAP-ΨdC | 5.3 | 16.6 | 0.8 | 2.6 | |

| 3′AZG5′ | T | 2.5 | 4.2 | 20.8 | 2.3 |

| MeAP-ΨdC | 1.8 | 19.4 | n.d. | 0.2 | |

| 3′AZA5′ | T | n.d. | 1.4 | 41.8 | n.d. |

| MeAP-ΨdC | 0.2 | 20.8 | n.d. | n.d. | |

TFO: 3′-GGAAGGG Z AGAGGAGGGA; Duplex: 5′-GAGGGAAGGG X AGAGGAGGGAAGC; DNA: 3′-CTCCCTTCCC Y TCTCCTCCCTTCG-FAM.

The highly general recognition ability of MeAP-ΨdC (8) for a CG pair was further demonstrated by triplex formation against the promoter sequence of the hTERT gene, the up-regulation of which is known to be associated with human carcinogenesis.56,57) The triplex-forming site in the target duplex DNA contains four CG inversion sites, with two of them consecutive, thus this sequence is difficult to target by TFO (Fig. 16). The MeAP-ΨdC or thymidine was incorporated into the positions corresponding to each of the four CG base pairs in TFO-Z′ or TFO-T, respectively. Triplex formation was analyzed by gel shift assay. TFO-Z formed a stable triplex with the target duplex, even at low concentrations (Fig. 16). It should be noted that MeAP-ΨdC is useful for the formation of a stable triplex, even in the presence of multiple and consecutive CG base pairs. On the other hand, natural type TFO-T did not form a stable triplex, as shown by the duplex bands at high concentrations. TFO-Z was applied to HeLa cells, and efficient inhibition of hTERT mRNA production was demostrated.55)

DNA in living organisms suffers from oxidative damage by reactive oxygen species to form a variety of oxidized nucleosides. 8-Oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG) is a representative metabolite derived from the oxidation of 2′-deoxyguanosine (dG), and is known to induce G:C to T:A transversion mutations in DNA. The intracellular level of 8-oxo-dG is related to diseases and aging. 8-Oxo-dG is removed from the genome and the nucleotide pool by DNA repair systems, then excreted from the cell; its level is a biomarker for oxidative damage in cells. Currently, 8-oxoguanine, 8-oxo-G and 8-oxo-dG are analyzed via HPLC-ECD, HPLC-MS, etc.58) In this study, we investigated the selective recognition of 8-oxo-dG in aqueous solution, and also in DNA. In addition, we also targeted other 8-oxidized guanosines, 8-nitroguanosine and 8-thioguanosine.

4.1. Receptor Molecules for 8-oxo-dG in SolutionIn designing a recognition molecule for 8-oxoguanine, the G-clamp was selected as a platform skeleton. It was expected that the benzyloxycarbonyl (Cbz) group at the aminoethoxy terminal of the G-clamp would work as a H-bond acceptor for the H-N7 of 8-oxo-dG, whereas N7 of the guanine base is not a H-bond donor (Fig. 17). As described below, the Cbz-G-clamp proved to be a suitably selective molecule for 8-oxoguanosine, and was thus named the oxoG-clamp.59)

The oxoG-clamp derivatives possess intrinsic fluorescence, which is selectively quenched by complex formation with 8-oxoguanosine. Therefore, their binding properties were investigated by titration experiments using bis(TBDMS) protected nucleoside derivatives in organic solvents. In contrast to the effective fluorescence quenching of oxoG-clamp (8) by 8-oxo-dG, no fluorescence quenching was observed with other nucleosides. Among a variety of 8-oxoG-clamp derivatives,60,61) that bearing a pyrenyethyloxycarbonyl group (EtPyr) exhibited the highest affinity. The ureido moiety (NHEt) returned the electivity of the molecule to dG, due to hydrogen bonding with the 7N of dG (Fig. 18).

To recognize 8-oxo-GTP in aqueous media, the cyclen-zinc complex was conjugated to 8-oxo-G-clamp by an expected ionic interaction with the triphosphate part (Fig. 19, Zn-receptor (10)). The ethyl linker between the conjugation and the benzyloxy group produced the optimized recognition property for 8-oxo-GTP in water.62) This Zn-receptor (10) was successfully applied to the detection of in-cell extracts. To discriminate between the fluorescence of the Zn-receptor at 460 nm and intrisic intracellular fluorescense, an Eu-receptor was developed. The Eu-receptor exhibited fluorescense at a higher wavelength and with a longer life span (Fig. 19, Eu-receptor (11)).63) As Zn- (10) and Eu-receptor (11) molecules penetrate into cells, they are expected to be used for the intracellular detection of 8-oxo-dGTP. The phenoxazine skeleton was also used to develop covalent capture molecules for 8-nitroguanine nucleoside and nucleotides.64,65)

The formation of 8-oxo-dG in DNA is suggested to be a distinctive non-random pattern,66) along with sequence-specific DNA damage in the -GGG-context.67,68) Due to the biological importance of 8-oxo-dG sequencing, the ability to discriminate between 8-oxo-dG and dG within DNA is important. 8-oxo-dG in DNA is detected by antibodies,69) small molecules,70,71) nanopore systems,72) high mass accuracy mass spectrometry,73) and engineered luciferase,74) but there is no method for the analysis of 8-oxo-dG in intact DNA. The 8-oxoG-clamp has proven useful for 8-oxo-dG detection in solution; however, the 8-oxoG-clamp in ODN has a limited ability to sense 8-oxodG in DNA.75) Accordingly, we designed a new recognition molecule by focusing on the conformational isomers around the glycosidic bond of 8-oxodG in DNA.76)

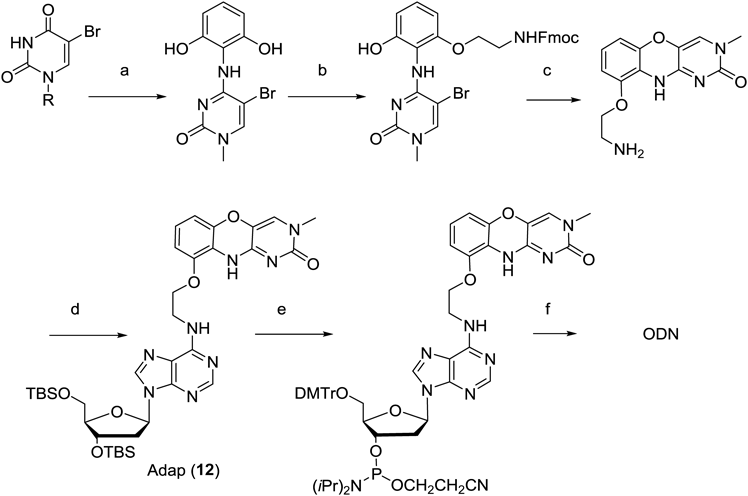

The 8-oxoguanine base prefers the syn conformation, and forms a base pair with dA at the Hoogsteen face of 8-oxodG. A 1,3-diazaphenoxazine unit then connects to the 6-amino group of dA through the ethoxy spacer by base pair formation at the Watson-Crick face of 8-oxodG (Fig. 20). This new adenosine-diazaphenoxazine analog has been named Adap (12).

The key intermediate, an aminoethoxy derivative of 1,3-diazaphenoxazine, was synthesized from N1-methyl-5-bromouracil, and was reacted with 2′O-,5′O-diTBS-6-chloroadenosine to produce the Adap monomer. The Adap was incorporated into ODN with a variety of sequences by standard amidite chemistry using the amidite derivative of Adap (Chart 4).

(a) (1) HMDS, CH3I, MeCN; (2) PPh3, CCl4, CH2Cl2, 2,6-dihydroxy-aniline, DBU; (b) N-Fmoc-2-aminoethanol, PPh3, DIAD, CH2Cl2; (c) 7M ammonia in MeOH, (d) 2′O-,5′O-diTBS-6-chloroadenosine, DIPEA, 1-propanol; (e) (1) TBAF, THF, (2) DMTrCl, pyridine, (3) 2-Cyanoethyl-N,N′-diisopropylchlorophosphorodiamidite, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, (f) DNA automated synthesizer.

The base pair forming selectivity of Adap (12) with 8-oxo-dG was investigated by measuring its thermal stabilization effects (Fig. 21). Base pair selectivity was clearly shown by the fact that the Adap-8-oxo-dG gave the highest melting temperature compared with other combinations using natural nucleobases.

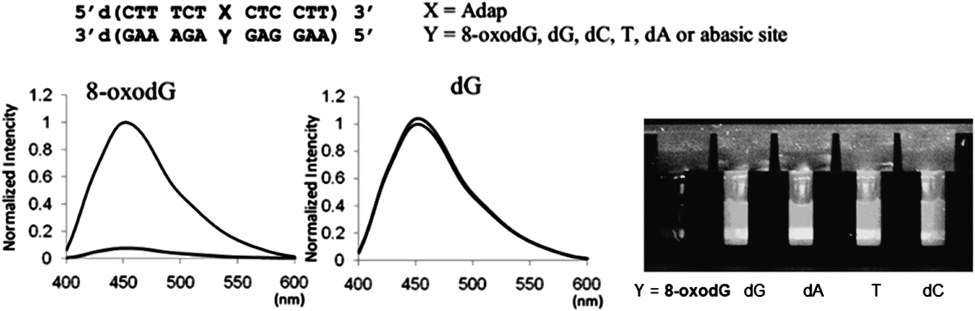

Base-pair selectivity of Adap with 8-oxodG in DNA was further proven by experiments in which the fluorescence of Adap was efficiently quenched, whereas no quenching occurred for dG, dC, dT, dA or the abasic site (Fig. 22). The quenching efficiency is sufficiently high that the presence of 8-oxodG in the duplex DNA can be visually detected. The formation of a tight complex between Adap and 8-oxodG plays a key role in this efficient and selective fluorescent quenching.

A selective base pair of Adap with 8-oxo-dG was applied to an OFF-ON type fluorescence sensor based on the FRET strategy (fluorescence resonance energy transfer).77,78) For further sensitive detection, Adap triphosphate (dAdapTP) was applied to single-base extension technology, which is widely used in performing genotyping.79) When DNA polymerase selectively incorporated dAdapTP into the primer DNA for 8-oxo-dG, not for dG in the template DNA, a single nucleotide extension was observed only for the 8-oxo-dG containing template DNA. The triphosphate of Adap (dAdapTP) was synthesized starting from the Adap diol. In single nucleotide primer extension reactions using a 25-mer template DNA and a FAM-labeled 15-mer primer DNA, as well as a Klenow fragment (Kf exo−), preferential extension was observed for the templates containing 8-oxo-dG or T; somewhat lower efficiency was found for the dA template; and no significant extension occurred for the template ODNs that included dG or dC. It was not desired, but dAdapTP was incorporated opposite T even better than 8-oxo-dG because Adap has a dA skeleton. However, importantly, 8-oxo-dG and dG in the template ODNs was completely discriminated.80)

This primer extension technology was applied to the sequence-specific detection of 8-oxo-dG in telomeric DNA. The oxidation of dG in telomeric DNA is well known to be related to aging. Telomeric DNA is more susceptible to oxidative base damage than non-telomeric regions in vivo. Cy5- and Cy3- primers were designed to detect 8-oxo-dG at the X and Y of the template (TTA GGG)4 of human telomeric DNA, respectively (Fig. 23). The Cy5- and Cy3-primers exhibited a selective extension for the respective template with 8-oxo-dG at X or Y, indicating that 8-oxo-dG in a human telomere sequence can be selectively detected. This method was applied to detect 8-oxo-dG in telomere DNA prepared from H2O2-treated HeLa. HeLa cells were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of H2O2, and extracted DNA was used as the template for a single nucleotide extension. The bar graph in Fig. 23 illustrates the Cy5-primer extension reaction, indicating that the incorporation of Adap increased in a dose-dependent manner according to the concentration of H2O2 solution in the media.

(Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

In this study, we have focused on a single nucleotide mutation (a point mutation) in DNA or RNA, and also on the 8-oxidized guanine base as a main cause of this mutation. Our approach has been termed gene-targeting chemistry, and a variety of recognition molecules have been developed in the three categories summarized in this review: (1) the RNA-targeting reaction with cross-linking or functionality-transfer oligonucleotides; (2) the formation of non-natural triplex DNA for sequence-specific inhibition of transcription by the newly designed non-natural nucleotides; and (3) the recognition of 8-oxidized-guanosine derivative by artificial receptor molecules. This study has established the concept of genome-targeting chemistry, and has lead to the creation of novel functional molecules, which will be useful in further applications.

These studies have been carried out at the Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kyushu University. I would like to thank past and present staff and students of this laboratory: Professors F. Nagatsugi, O. Nakagawa, Y. Taniguchi, Y. Fuchi and Y. Abe, as well as the many participating students whose names are not listed in this paper. I would also like to express my sincere appreciation of the late Professor Emeritus K. Koga of the University of Tokyo, and Professor Emeritus M. Maeda of Kyushu University for their encouragement in this research field. This study has been financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B), (A), (S) and for Challenging Exploratory Research), the Uehara Memorial Foundation, and the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders. I also gratefully acknowledge the financial support and collaboration of Professor Emeritus K. Kataoka for his CREST project (Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST)).

The author declares no conflict of interest.

This review of the author’s work was written by the author upon receiving the 2017 Pharmaceutical Society of Japan Award.