2019 年 67 巻 9 号 p. 992-999

2019 年 67 巻 9 号 p. 992-999

A three-dimensional (3D) printer is a powerful tool that can be used to enhance personalized medicine. A fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer can fabricate 3D objects with different internal structures that provides the opportunity to introduce one or more specific functionalities. In this study, zero-order sustained-release floating tablet was fabricated using FDM 3D printer. Filaments comprising poorly water-soluble weak base drug, itraconazole (ITZ) and polymers (hydroxypropyl cellulose and polyvinylpyrrolidone) were prepared, and tablets with a hollow structure and different outside shell thicknesses were fabricated. In the 3D printed tablets, ITZ existed as an amorphous state and its solubility improved markedly. As the outside shell thickness of the tablet increased, drug release was delayed and floating time was prolonged. In the tablets with 0.5 mm of the upper and bottom layer thickness and 1.5 mm of the side layer thickness, holes were not formed in the tablets during the dissolution test, and the tablets floated for a long period (540 min) and showed nearly zero-order drug release for 720 min. These findings may be useful for improving the bioavailability of several drugs by effective absorption from the upper small intestine, with floating gastric retention system.

A three-dimensional (3D) printer is an attractive type of manufacturing equipment, which can easily fabricate 3D object under the control of computer software. It is widely used in many fields, such as architecture, aerospace engineering and healthcare.1–3) In the pharmaceutical field, since the shape and size of the object are simply changed using 3D computer aided design (CAD), a 3D printer is thought to be useful to fabricate a pharmaceutical dosage form whose dose and drug release rate are adjusted to meet individual patient characteristics and needs.4–6) Thus, 3D printing has received a lot of attention in recent years as a useful tool to enhance personalized medicine. Although there are several types of 3D printers, such as powder bed, semi solid extrusion, and fused-deposition modelling (FDM),7) FDM 3D printer is most commonly used for fabricating pharmaceutical dosage forms owing to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness.8)

For pharmaceutical applications of FDM 3D printer, filaments composed of drug and polymer are prepared, and then they are passed through a heated nozzle. The filaments are heated to upper its softening point and then extruded through a nozzle followed by deposited layer by layer. This fabrication process allows for structural changes of the object that provides the opportunity to introduce one or more specific functionalities. For example, 3D printed caplets with perforated channels were reported.9) In these caplets, the drug release profiles were modified by changing the width and length of the channel. Zhang et al. reported that it was possible to control the drug release by varying infill percentages and thickness of the outside layer of the tablet.10) They also reported when the thickness of outside layer was 1.6 mm, the tablet showed nearly zero-order drug release. Therefore, it is possible to fabricate the tablets which show several drug release patterns, such as immediate release, sustained release and zero-order drug release, by FDM 3D printer. Also, varying infill percentages and outside shell thicknesses can adjust density and hardness of the tablets. By harnessing these features of FDM 3D printer, functional dosage forms, such as a floating dosage form as gastro-retentive dosage form, can be prepared.11,12) Tagami et al. fabricated tablets composed of polyvinylalcohol as a polymer and curcumin as a model drug with different infill percentages and reported that when the infill percentage was less than 60%, the tablets floated in the test solution (0.1% tween 80 aqueous solution) for over 30 min.11) Chai et al. fabricated tablets composed of hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC) as a polymer and domperidone (DOM) as a model drug with different shell numbers in addition to infill percentages and reported that the tablet with an hollow structure (infill percentage of 0%) and a shell number of 2 floated for more than 10 h and showed sustained drug release for 12 h in 0.1 N HCl solution.12) In addition, in vivo pharmacokinetic study using rabbits, the tablets floated in the stomach and improved the bioavailability of weakly base drug DOM whose absorption site are limited to upper small intestine. These reports suggest that FDM 3D printer is useful for adding one or more functionalities to the tablet by structural changes and the combination of several functions such as floating and controlled release by the FDM 3D printer will make a novel value for oral dosage form.

Generally, when considering floating dosage forms prepared by conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing methods, it is desired that the dosage forms show zero-order sustained-release. In fact, it was reported that zero-order sustained-release floating tablets presented a more stable plasma concentration compared with the market tablet.13) Therefore, several zero-order sustained-release floating tablets had been developed using conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing methods, such as osmic pump and dry coating.14,15) However, in case of using these methods, the process was complex and required many additives. On the other hands, as mentioned above, since the structure of the dosage form is easy to be changed by FDM 3D printer, it is expected to be used to fabricate a zero-order sustained-release floating dosage form easily. Additionally, for FDM 3D printer, it is possible to adjust the hardness and floating property of the tablet to meet individual gastric motility, thus providing more favorable dosage properties than the tablet prepared by conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing methods. However, there are no reports of FDM 3D printed tablet that achieve both floating and zero-order drug release for a long period. Thus, there is a need to evaluate what type of structural change make it possible for 3D printed tablet to show zero-order drug release for a long period with floating.

The aim of this study was to develop zero-order sustained-release floating tablets via FDM 3D printer. Poorly water-soluble weak base drug, itraconazole (ITZ), whose absorption site are limited to upper small intestine,16) was selected as a model drug. HPC and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were used as polymers. HPC was used to provide 3D printed tablets which have a tight structure and a long floating period. PVP is widely used to prepare amorphous solid dispersion (ASD) as solubility enhancer.17) Since FDM 3D printer is considered to be an extension of hot melt extrusion technology and it has been reported that a crystalline drug can be changed to amorphous state in 3D printed tablets,18–20) PVP was used in this study to change ITZ from crystalline state to amorphous state and improve its solubility. Filaments composed of ITZ and polymers were prepared, and tablets with a hollow structure and different outside shell thicknesses were fabricated using FDM 3D printer. The physicochemical properties, solubility, tablet properties, floating and dissolution properties of the obtained tablets were evaluated.

ITZ (Hanmi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) was selected as a model drug. HPC (HPC-SL) was provided by Nippon Soda Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). PVP (Kollidon K-25) was provided by BASF Japan Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of Drug Loaded FilamentsA total of 100 g of drug and polymers were manually mixed (mixture composition: 20% ITZ, 65% HPC, 15% PVP) in a polyethylene bag for 5 min. The blended physical mixture was loaded into a single-screw extruder (Filabot Original EX2, Filabot, VT, U.S.A.). The extruder was operated at 35 rpm and the mixtures were extruded at 135°C through a 1.75-mm nozzle. For the fabrication of an object using FDM 3D printer, the filament needs to be fed into a heating nozzle by feeding gear. To achieve continuous high-throughput FDM printing, the mechanical property of the filaments is very important. When the filament is too soft, it is squeezed aside by the gear. In contrast, when the filament is too brittle, it is broken by the feeding gear.21,22) In this study, when the content of PVP was low, the filament was too soft, and when the content of PVP was high, it was too brittle to fabricate using FDM 3D printer. When the filaments contained drug and polymers above mentioned compounding ratio (20% ITZ, 65% HPC, 15% PVP), they were feedable and used for further study.

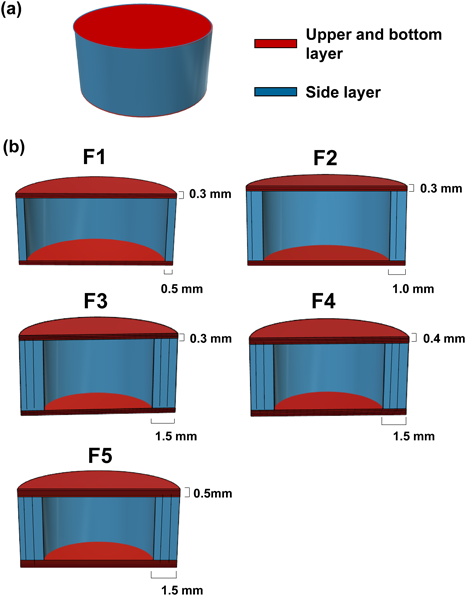

Tablet Design and 3D PrintingTablets were designed using 3D CAD software (123D Design; Autodesk Inc., San Rafael, CA, U.S.A.). The tablets were designed as a flat-face plain tablet (diameter 9.6 mm, thickness 5.6 mm) and a hollow structure (infill percentage of 0%) with different outside shell thicknesses (Fig. 1 and Table 1). We designed tablets whose side layer thickness was thicker than that of the upper and bottom layer. In this study, the drug release and floating properties of the tablets were evaluated by the paddle method (as described in Dissolution and Floating Study of Tablets). In the paddle method, it was reported that the flow in the apparatus was strongly dominated by the tangential component of the velocity.23) Therefore, it was thought that the side layer of the tablet was eroded easier by the flow than the upper and bottom layers, and thus, we used the design as mentioned above for assuring the floating property of the tablets.

(a) overall and (b) cross-sectional views. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

| Formulation | Thickness of upper and bottom layer (number of layer) | Thickness of side layer (number of layer) |

|---|---|---|

| F1 | 0.3 mm (3) | 0.5 mm (1) |

| F2 | 0.3 mm (3) | 1.0 mm (2) |

| F3 | 0.3 mm (3) | 1.5 mm (3) |

| F4 | 0.4 mm (4) | 1.5 mm (3) |

| F5 | 0.5 mm (5) | 1.5 mm (3) |

A commercial FDM 3D printer (MF2200-D, Mutoh industries Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with extruder head (nozzle diameter: 0.5 mm) was used to fabricate the tablets. The printing parameters were set as follows: extruder temperature: 185°C; platform temperature: 55°C; nozzle travel speed: 80 mm/s. We thought it was important to prevent gastrointestinal tract fluids from penetrating into the hollow of the tablet to successfully prepare a long-term floating tablet. Generally, when the height of the layer is thin, the roughness of the tablet surface is improved.24) Thus, each layer is tightly bound, and the hardness of the tablet increases. If the tablet hardness is high, the tablet is less collapsed, and it is possible to prevent gastrointestinal tract fluids from penetrating into the hollow of the tablet. Thus, the height of the layer was set to 0.1 mm which was minimum setting value of FDM 3D printer used in this study.

Scanning Electron Microscopy Observation of TabletsThe surface profile of the tablets was observed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM; Miniscope® TM3030, Hitachi High-Technologies Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The samples were placed on double-sided adhesive tape and sputter coated with platinum under vacuum prior to imaging.

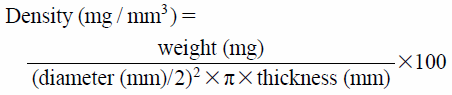

Characterization of TabletsThe thickness and diameter of tablets were measured using a digital caliper (digimatic caliper 500-302, Mitutoyo Co., Ltd., Kanagawa, Japan) (n = 10). The weights of the tablets were measured using an electronic balance (AT200, Mettler-Toledo, Columbus, OH, U.S.A.) (n = 10). Density was calculated according to the following equation.

|

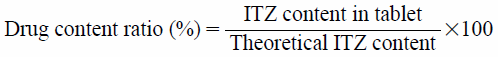

The crushing strength of the tablets was measured as the tablet hardness using a hardness tester (DC-50, Okadaseiko Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (n = 10). To determinate the drug content, one tablet was placed in a conical flask containing 100 mL of acetonitrile under magnetic stirring until complete dissolution. The concentration of the solutions was measured with HPLC (2010C-HT, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), using a C18 column (150 × 3 mm 3 µm), maintained at 40°C. The flow rate of the mobile phase consisting of 70% of acetonitrile and 30% of water was 0.3 mL/min and the detection was performed at a wavelength of 236 nm (n = 3). The drug content ratio was calculated according to the following equation.

|

Each sample (crystalline ITZ, HPC, PVP, physical mixture (PM), milled filament and milled tablet [F1]) was analyzed by a powder X-ray diffractometer (Mini Flex II, Rigaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Samples were scanned from 2 theta = 5° to 50° using a 4° step width and a 1 s time count. The wavelength of the X-ray was 1.5418 nm using a Cu source and a voltage of 30 kV, 15 mA.

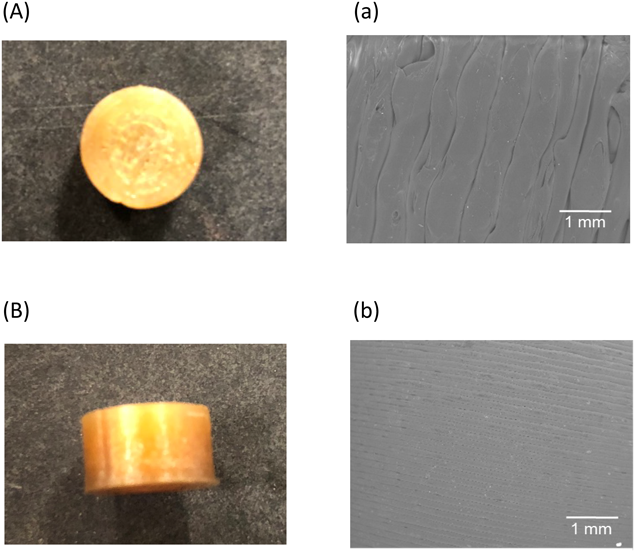

Differential Scanning Calorimetry AnalysisTen milligrams of each sample (crystalline ITZ, HPC, PVP, PM, milled filament and milled tablet [F1]) were placed into an aluminum pan (P/N SSC000E030 Open Sample Pan φ5, Seiko Instruments Co. Ltd., Chiba, Japan) and analyzed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; DSC7020, Hitachi High-Tech Science Co., Ltd.). The heating rate was 10°C/min and the nitrogen gas flow was 40 mL/min. The sample was heated from 30 to 200°C.

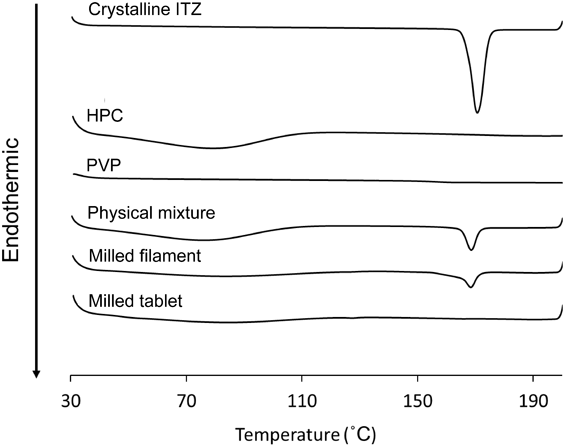

Dissolution Study of Crystalline ITZ, Milled Filament and Milled TabletThe drug dissolution profiles of each sample (ITZ, milled filament, milled tablet [F1]) (n = 3) was evaluated using the paddle method listed in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia 17th Edition (JP 17th). The test medium was 300 mL of JP 1st Fluid. The medium temperature was set to 37.0 ± 0.5°C and the paddle speed was 200 rpm. A sample containing 90 mg equivalent of ITZ was placed in the test medium. At each time point (1, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240, 360, 480, 720 and 1440 min), 5 mL of the test solution was withdrawn. The sample was passed through a 0.2-µm membrane filter. The amount of ITZ released into the medium was analyzed using a HPLC method with the same chromatographic conditions as the content assay (as shown in Characterization of Tablets).

Dissolution and Floating Study of TabletsThe drug dissolution profiles of the tablets (n = 3) was evaluated using the paddle method listed in JP 17th. The test medium was 900 mL of JP 1st Fluid. The medium temperature was set to 37.0 ± 0.5°C and the paddle speed was 200 rpm. The tablets were placed in the test medium. At each time point (5, 15, 30, 60, 120, 240, 360, 480, 600 and 720 min), 5 mL of the test solution was withdrawn. The sample was passed through a 0.2-µm membrane filter. The amount of ITZ released into the medium was analyzed using a HPLC method with the same chromatographic conditions as the content assay (as shown in Characterization of Tablets). Floating tablets were photographed hourly to observe their floating state.

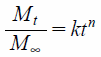

Drug Release KineticsThe experimental data were kinetically evaluated using the Korsmeyer–Peppas25) and zero-order models. These equations were fitted to the results of the dissolution tests by a nonlinear least-squares method using the statistics software package Origin® 9.1 (Originlab Co. Ltd., Northampton, MA, U.S.A.). The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm was used for nonlinear fitting,

Korsmeyer–Peppas equation:

|

Zero-order equation:

|

where Mt is the amount of drug released at time t, M∞ is the amount of drug released after an infinite amount of time, k is release rate constant, and n is the release exponent. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used as a measure of the goodness of fit of the experimental data. R2 was calculated according to the following equation:

|

where N is the number of experimental data points, yi is the measured value,  is the estimated value and

is the estimated value and  is the mean of measured values.

is the mean of measured values.

Each pair of samples which have the same upper and bottom layer thickness (F1, F2 and F3), or the same side layer thickness (F3, F4 and F5) was analyzed separately using Student t-test with Bonferroni correction. A probability value of p < 0.017 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

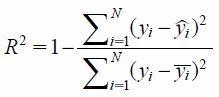

The photographs and SEM images of the 3D printed tablet (F1) are shown in Fig. 2. F1 had a smooth surface and a tight structure in the upper and bottom layers (Figs. 2 A and a) and side layer (Figs. 2 B and b). As is the case with F1, all other tablets (F2 to F5) had smooth surfaces and a tight structure (data not shown). Table 2 shows the physical properties of the tablets. In all tablets, because the standard deviations of the diameter (±0.04–0.14 mm), thickness (±0.04–0.07 mm) and weight of tablets (±9.24–18.4 mg) were small, the fabrication process shows low variability. The diameter and thickness of the tablets were close to the designed value. However, the diameter of F3 increased significantly compared with F1 and F2, the thickness of F5 increased significantly compared with F3 and F4. In this study, when the thickness of side layer increased, the layer increased towards inside of the tablet, while keeping the tablet diameter (9.6 mm). Specifically, when the side layer thickness was 1.5 mm, the diameter of the hollow was 6.6 mm. It has been reported that as the diameter of the tablet decreased, molding accuracy was reduced, and the diameter of the tablets were larger than expected value.11) In this study, it was thought that when the thickness of the side layer increased, the diameter of the hollow decreased, and molding accuracy was reduced, thus the diameter of F3 increased significantly compared with F1 and F2. On the other hands, in F1, F2, F3 and F4, the thickness of the tablets was slightly smaller than that of designed tablet. Because the tablet had hollow structure, when the layer of the upper part was deposited, there was no support under the layer and the upper part of the tablet was slightly dented. In F5, because five layers were deposited, there was sufficient layer and the upper part of the tablets didn’t dent. Therefore, the thickness of the tablet was increased significantly compared with F3 and F4.

(Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

| Diameter (mm) | Thickness (mm) | Weight (mg) | Density (mg/mm3) | Hardness (N) | Drug content ratio (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 9.56 ± 0.04 | 5.58 ± 0.04 | 167 ± 12.7 | 0.41 ± 0.03 | 16.9 ± 3.31 | 108 ± 4.64 |

| F2 | 9.55 ± 0.06 | 5.59 ± 0.04 | 253 ± 9.24** | 0.63 ± 0.02** | 60.3 ± 12.2** | 105 ± 4.12 |

| F3 | 9.69 ± 0.06**,†† | 5.57 ± 0.04 | 362 ± 18.4**,†† | 0.89 ± 0.04**,†† | 140 ± 30.4**,†† | 102 ± 1.72 |

| F4 | 9.66 ± 0.14 | 5.57 ± 0.07 | 385 ± 15.7‡‡ | 0.92 ± 0.03 | 181 ± 22.6‡ | 105 ± 0.14 |

| F5 | 9.80 ± 0.13 | 5.68 ± 0.07‡‡, ## | 403 ± 14.7‡‡, # | 0.94 ± 0.02‡‡ | 202 ± 37.7‡‡ | 107 ± 0.88 |

Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) (n = 10, Drug content ratio: n = 3). ** p < 0.0033, compared with F1. †† p < 0.0033, compared with F2. ‡ p < 0.017, ‡‡ p < 0.0033, compared with F3. # p < 0.017, ## p < 0.0033, compared with F4.

As the thickness of the outside layer (side layer, and upper and bottom layer) increased, weight, hardness and density of the tablet increased significantly. Recently, Zhang et al. reported that as the thickness of the outside layer of the tablet fabricated by FDM 3D printer increased, weight, hardness and density of the tablet increased.10) This is consistent with the results obtained in this study and suggests that for tablets fabricated using FDM 3D printer, the outside layers of the tablet affect weight, hardness and density of the tablet. Generally, in order to float in the stomach, the density of the dosage form should be less than the gastric content (1.004 mg/mm3).26) In this study, since the maximum value of the density was 0.94 mg/mm3 (F5), it was thought that any tablet could float in gastric fluid. The drug content ratio was not affected by the thickness of the outside layer and was close to the theoretical value in all tablets. Taken together, the results indicated that all tablets were successfully printed with the designed 3D structures.

Powder X-Ray Diffraction and Differential Scanning Calorimetry AnalysisThe results of powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) are shown in Fig. 3. In crystalline ITZ, the peaks were observed at 17, 20 and 26°. These peaks were observed in the PM and the milled filament; however, in the milled filament, the intensity of these peaks was weaker than that of the PM. In contrast, they were not observed in the milled tablet. The results of DSC are shown in Fig. 4. In crystalline ITZ, PM and milled filament, the endothermic peak corresponding to the melting point of ITZ was observed at approximately 160°C; but in the milled filament, the peak intensity was weaker than that of the PM. In the milled tablet, this peak disappeared. The results of PXRD and DSC suggested that ITZ partially existed as an amorphous state in the filament and completely existed as an amorphous state in the 3D printed tablets. This is because the 3D printing temperature (185°C) was higher than the melting point of crystalline ITZ (160°C). In this study, filaments were prepared by a hot melt extruder and extruded at 135°C through a 1.75-mm nozzle. When the manufacturing temperature of the filament was too high (more than 135°C), the viscosity of the polymers and drug mixture decreased and the filament lost its shape, and thus it could not be used in the 3D printer. Therefore, it was difficult to prepare a filament at a higher temperature than the melting point of the drug (160°C). In 3D printing, because the filaments had to be extruded through a nozzle whose diameter was smaller than that of the filament, the viscosity of the heated filament needed to be decreased. Thus, a high extruder temperature more than the melting point of ITZ was needed so that ITZ melted and was changed to an amorphous state. At temperatures less than 185°C, which was selected as the 3D printing temperature, only the peak corresponding to the melting point of ITZ was changed and thus, no degradation of polymers and drug had occurred.

The dissolution profiles of crystalline ITZ, milled filament and milled tablet are shown in Fig. 5. The drug concentrations of the milled filament and tablets showed a maximum value at 30 and 60 min (filament: 142.4 µg/mL, tablet: 272.6 µg/mL), then they decreased. However, even at 1,440 min, the drug concentration of the milled filament and tablets maintained the supersaturated state and were sufficiently higher than that of crystalline ITZ. The drug concentration of the milled filament, tablet and crystalline ITZ at 1440 min were 71.3, 94.3 and 3.07 µg/mL, respectively. Comparing the milled filament with the milled tablet, the drug concentration of the milled tablet was higher. This was considered to occur due to ITZ partially existing as amorphous state in filament and existing as amorphous state in tablet as described in Powder X-Ray Diffraction and Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis. Based on these results, the drug content in the tablet was set to within 84 mg so that the concentration of the drug during the dissolution test did not exceed the solubility of 3D printed tablet at 1440 min (94.3 µg/mL).

Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

Figure 6 shows photos of tablets during the drug dissolution and floating test. In F1, erosion of the tablet was immediately initiated, the tablet then sank and fragmented at 120 min (Fig. 6a). F2 showed a similar behavior. In F3, the drastic shape changes observed in F1 and F2 were not observed until 240 min, but a hole was observed on the upper and bottom part of the tablet at 300 min, and the tablet sank at 360 min (Fig. 6b). Because the side layer of F3 was thicker than that of F1 and F2, the penetration of test solution through it was inhibited, but as the time proceeds, the upper and bottom layers whose thicknesses were thinner than the side layer dissolved. In F4 similar to F3, the hole was observed at 420 min and the tablet sank at 480 min. In F5, the hole was not observed and the tablet floated for 540 min and dissolved at 600 min (Fig. 6c). Although Chai et al. fabricated 3D printed tablets that had hollow and different numbers of side layers, they reported that when the shell number was less than or equal to 3, it did not affect the floating time, but when it was greater than or equal to 4, the tablet sank within an hour because of its high density.12) Because the 3D printer used in their report was a commercial FDM 3D printer (Replicator X2, MakerBot Inc., NY, U.S.A.) and the nozzle diameter was 0.4 mm, when the shell number was varied from 1 to 4, the shell thickness varied from 0.4 to 1.6 mm. Therefore, the outside tablet thickness in their study was similar to that in our study. Nevertheless, the results of their report were inconsistent with those of our study likely because of the different polymers used to fabricate the 3D printed tablet. In their report, only HPC was used as a polymer, whereas HPC and PVP were used in our study. PVP is widely used as a solubility enhancer in the pharmaceutical field.17) In the tablets fabricated by FDM 3D printer, it was reported that the drug release was accelerated by adding PVP in the formulation.27) In this study, the drug release was accelerated by PVP and consequently the test medium could easily penetrate into the tablet through the region where the drug was released. As a result, the tablet shape collapsed more easily compared with using only HPC, and the effects of shell thickness on floating time were clearly observed. Additionally, in Chai et al.’s report, the paddle speed of the floating test was 50 rpm, which was milder than that of our study (200 rpm). Therefore, it was considered that the effects of shell thickness on the floating properties were more evident in our study.

(a) F1, (b) F3 and (c) F5. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

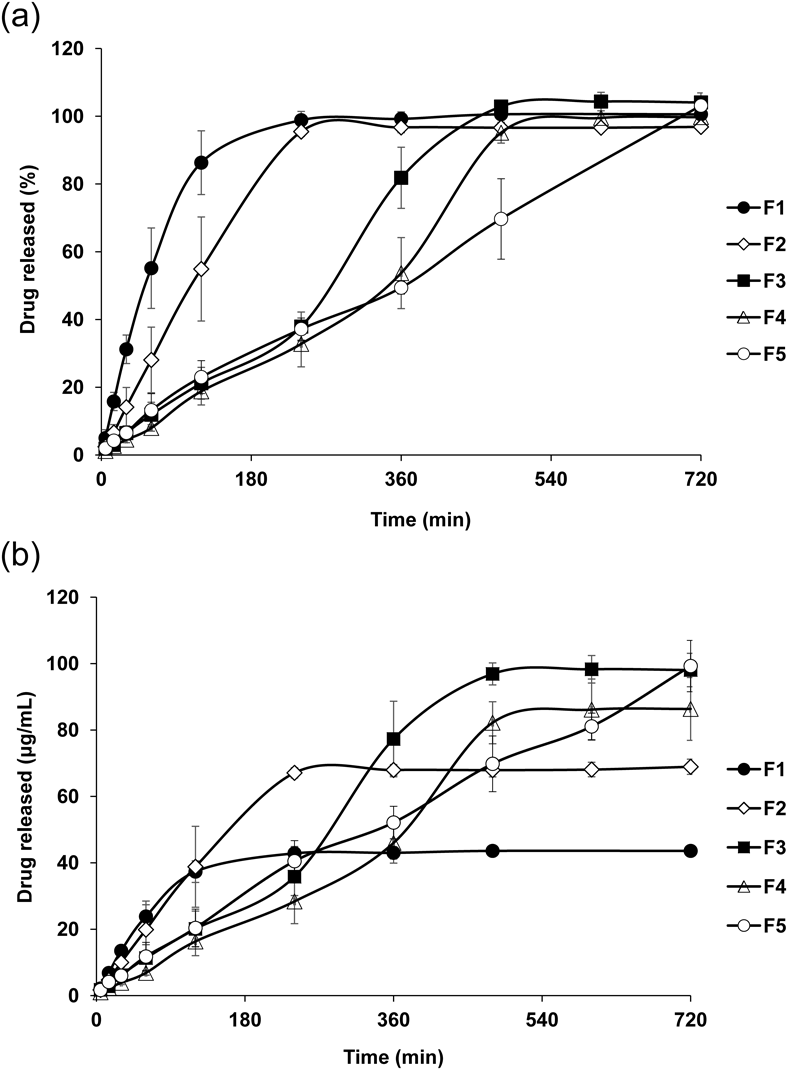

Figure 7 shows the drug release profiles of the 3D printed tablets. Comparing the tablets with different side layer thicknesses (F1, F2 and F3), as the thickness increased, the drug release was delayed. In F1 and F2, almost 100% of the drug was released at 240 min. In F3, the drug release at 240 min was about 40% (Fig. 7a). Since weight and drug content of these tablets were markedly different, the amount (µg/mL) of released drug were evaluated for considering the effect of weight and drug content of tablets (Fig. 7b). Similar with evaluating the drug release percentage (Fig. 7a), F3 showed the slowest drug release rate among the three tablets (F1, F2 and F3). Recently, Zhang et al. reported that the drug release from tablets fabricated by FDM 3D printer was delayed as the thickness of the side layer increased.10) Our results were similar to those in Zhang’s report. Thus, as the shell thickness increased, the layers became more strongly connected and the tablets collapsed less in the test medium. These results suggest that the drug release rate of the tablet fabricated by FDM 3D printer can be adjusted by varying the outside shell thickness. Comparing the tablets with different upper and bottom layers (F3, F4 and F5), although similar drug release profiles were observed and the drug release linearly increased for 240 min for each type of tablet, the burst of drug release was observed in F3 from 240 to 360 min and in F4 from 360 to 480 min. These time points were consistent with the periods over which the holes were observed (Fig. 6b). Because the test medium penetrated into the inside of the tablets through the hole, the effective surface area for dissolution increased. In F5, the burst of drug release was not observed and the tablet released drug linearly for 720 min. It was revealed that the tablets with several drug release profiles were obtained by structural change. Considering the contents of the formulation, it had been reported that the drug release was accelerated by adding hydrophilic polymer such as PVP and polyethylene oxide in the formulation.27,28) Pietrzak et al. reported about the 3D printed tablets fabricated using Eudragit E, HPC-SSL, Eudragit RL and Eudragit RS, respectively. The tablets fabricated using Eudragit E or HPC-SSL showed immediate drug release (80% at 30 min, 80% at 75 min, respectively). On the other hands, the tablets fabricated using Eudragit RL or Eudragit RS showed sustained drug release (80% at 1080 min, 10% at 1080 min, respectively).24) Therefore, further experiment varying type and amounts of polymers would make it possible to change the drug release behavior more widely.

(a) released percentage and (b) released amount (concentration). Each data point represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

The drug release data of the 3D printed tablets were kinetically evaluated using the Korsmeyer–Peppas equation and a zero-order model. In the Korsmeyer–Peppas equation, if the test sample has a cylindrical shape, a release exponent value of n = 0.45 is considered consistent with a diffusion-controlled release behavior (Fickian diffusion), n = 0.89 is considered consistent with Case II transport (a polymer relaxation- or swelling-controlled mechanism) and zero-order release, and a value of n between 0.45 and 0.89 indicates superposition of both phenomena (anomalous transport).29) As shown in Table 3, the n values of F1, F2 and F5 are 0.7627, 0.8844 and 0.8135, respectively. Therefore, these drug release profiles were ascribed to anomalous transport. However, because the n value were close to 0.89, the drug release mechanism was considered to closely follow Case II transport. When the data were fitted to the zero-order model, the coefficient of determination (R2) were high (F1: 0.9759, F2: 0.9942, F5: 0.9899). In particular, F5 showed nearly zero-order drug release for a long period (720 min). Because two water-soluble and low viscosity grade polymers (HPC-SL and PVP Kollidon K-25) were used in this study, the polymers dissolved without the formation of a strong gel and these tablets showed zero-order drug release. On the other hands, in F3 and F4, the n values of Korsmeyer–Peppas equation were higher than 0.89 (F3: 1.3177, F4: 1.4116). Therefore, these drug release profiles were ascribed to super Case II transport. This is because that the burst of drug release was observed in the middle of the dissolution test (Fig. 7).

| Korsmeyer–Peppas | Zero-order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | n | R2 | Slope | R2 | |

| F1 | 2.2796 | 0.7627 | 0.9939 | 0.7207 | 0.9759 |

| F2 | 0.7574 | 0.8844 | 0.9979 | 0.4023 | 0.9942 |

| F3 | 0.0335 | 1.3177 | 0.9736 | 0.2082 | 0.9632 |

| F4 | 0.0149 | 1.4116 | 0.9828 | 0.1798 | 0.9655 |

| F5 | 0.4819 | 0.8135 | 0.9967 | 0.1466 | 0.9899 |

In this study, using FDM 3D printer, we successfully developed 3D printed tablets that can float for more than 540 min in the test medium and showed zero-order drug release for 720 min. Several zero-order sustained-release floating dosage forms containing drugs whose absorption site are limited to upper small intestine had been developed using conventional pharmaceutical manufacturing methods.13,30) For example, Guan et al. developed the capsule containing famotidine, using osmic pump technology.30) In their report, they prepared the capsules, which floated and showed zero-order drug release for 12 h in simulated gastric fluid medium (pH 1.2). They evaluated the pharmacokinetic profiles of the capsules in beagle dogs. The average peak plasma concentration was significantly lower than that of market tablets, and drug side effect was mitigated. However, the area under the plasma concentration versus time curve (AUC) was increased significantly in case of the capsules compared with the market tablets. Gong et al. developed the tablet containing alfuzosin hydrochloride, using compression coating technology.13) They evaluated the pharmacokinetic profiles of the tablets in rabbits. The mean residence time and AUC showed higher value than that of the market prolonged release tablets. In addition, the tablet presented a more stable plasma concentration in rabbits compared with the market tablets. Their reports suggested that zero-order sustained-release floating dosage form could safely and stably improve the bioavailability (BA) of drugs whose absorption site are limited to upper small intestine. In this study, we presented that FDM 3D printer could be used to fabricate the tablets with several floating and drug release profiles. Although further study in vivo is necessary, it might be possible to design tablets whose floating time and drug release rate are accurately adjusted and therefore to improve BA more safely and stably.

The aim of this study was to develop 3D printed tablets that achieve both floating and zero-order sustained-release using FDM 3D printer. The standard deviations of the properties of the obtained tablets were small, which indicated that there was very little variation in the fabrication process. ITZ existed as an amorphous state in the 3D printed tablets and the solubility of ITZ was markedly improved. In the drug dissolution and floating test, the outside shell thickness of the tablets affected the drug dissolution and floating profile. As the outside shell thickness increased, the drug release was delayed and the floating time was prolonged. When the upper and bottom layer thickness was 0.5 mm and side layer thickness was 1.5 mm, holes were not formed in the tablets during the dissolution test and the tablets floated for a long period (540 min) and showed nearly zero-order drug release for 720 min. Our results provide useful knowledge for designing studies that aim to improve the BA of several poorly water-soluble weak base drugs.

The authors thank BASF Japan Ltd. and Nippon Soda Co., Ltd. for kindly providing reagents used in this study. We thank Renee Mosi, Ph.D., for editing a draft of this manuscript.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.