2020 Volume 68 Issue 1 Pages 91-95

2020 Volume 68 Issue 1 Pages 91-95

Magnolia Flower is a crude drug used for the treatment of headaches, toothaches, and nasal congestion. Here, we focused on Magnolia kobus, one of the botanical origins of Magnolia Flower, and collected the flower parts at different growth stages to compare chemical compositions and investigate potential inhibitory activities against interleukin-2 (IL-2) production in murine splenic T cells. After determining the structures, we examined the inhibitory effects of the constituents of the bud, the medicinal part of the crude drug, against IL-2 production. We first extracted the flower parts of M. kobus from the bud to fallen bloom stages and analysed the chemical compositions to identify the constituents characteristic to the buds. We found that the inhibitory activity of the buds against IL-2 production was more potent than that of the blooms. We isolated two known compounds, tiliroside (1) and syringin (2), characteristic to the buds from the methanol (MeOH) extract of Magnolia Flower. Moreover, we examined the inhibitory activities of both compounds against IL-2 production and found that tiliroside (1) but not syringin (2), showed strong inhibitory activity against IL-2 production and inhibited its mRNA expression. Thus, our strategy to examine the relationship between chemical compositions and biological activities during plant maturation could not only contribute to the scientific evaluation of medicinal parts of crude drugs but also assist in identifying biologically active constituents that have not yet been reported.

T cells play an important role in autoimmune diseases and chronic inflammatory conditions.1) They are typically activated in response to T cell receptor (TCR)-antigen binding or from the plant-based lectin concanavalin A (Con A).2–4) Stimulated T cells produce interleukin-2 (IL-2), one of the essential cytokines required for T cell immunity, which can trigger downstream signalling events that activate extracellular signal regulated protein kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2),5–7) which ultimately induces T cell proliferation that is often implicated in inflammation.8) Therefore, the inhibition of IL-2 released by activated T cells could result in anti-inflammatory effects. Measuring IL-2 production from Con A- or TCR-activated T cells is widely used to evaluate anti-inflammatory effects. This method can be used to identify potential anti-inflammatory drugs. Typical compounds known to inhibit IL-2 production are cyclosporin A9,10), tacrolimus,11,12) and suplatast.13)

Magnolia Flower (辛夷) is a crude drug defined as the buds of Magnolia salicifolia, M. kobus, M. biondii, M. sprengeri, or M. heptapeta (M. denudata) in the Japanese Pharmacopoeia 17th edition.14) Magnolia Flower has been often used for the treatment of headaches, toothaches, and nasal congestion, showing anti-allergy15–17) and anti-inflammatory18) activity. Several active constituents exhibiting various biological activities from Magnolia Flower have been identified, according to the literature, including lignans with IL-2 inhibitory19) and cholesterol-lowering20) activity, neolignans with anti-inflammatory21) and anti-vasculogenesis22) activity, and volatile oils with anti-inflammatory activity.23) There have also been many reports on the isolation of volatile oils,24) lignans,25) neolignans,25) phenylpropanoids,26) alkaloids,27) monoterpene glycosides,28) and flavonoids15) from Magnolia species in efforts to study biological activity.

Previous studies have reported that variations in the volatile oils of the buds of Magnolia species were influenced by seasonal changes,24) differences in habitats,29) and botanical origins.30) However, the relationship between chemical compositions and pharmacological effects of Magnolia Flower based on seasonal variation has not been examined and the biologically active constituents influenced by seasonal change have also not been identified.

In the present study, we collected the flower parts of M. kobus at different growth stages and elucidated the chemical compositions of the extracts using high performance (HP)TLC, with good results in preliminary tests; further, we investigated potential biological activity by examining the inhibitory activity against IL-2 production in murine splenic T cells. Furthermore, we determined the structures and examined the inhibitory activities against IL-2 production of the constituents characteristic to the bud, which is the medicinal part.

In our previous report,7) we have shown that U0126 (an inhibitor of the ERK1/2 pathway) significantly suppressed IL-2 production to 15% in stimulated T cells. Using the same method to analyse IL-2 production, in this report, we evaluated the inhibitory activities of samples from Magnolia species against ConA-induced IL-2 production.

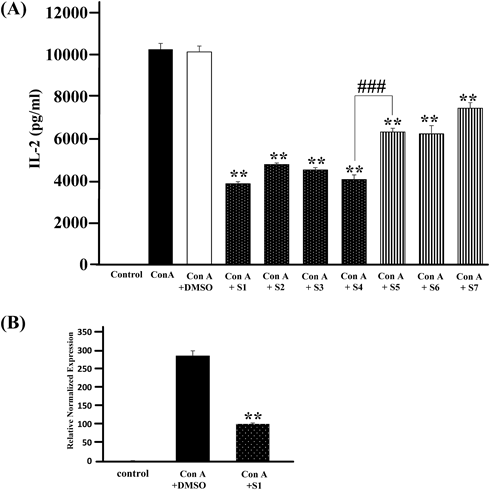

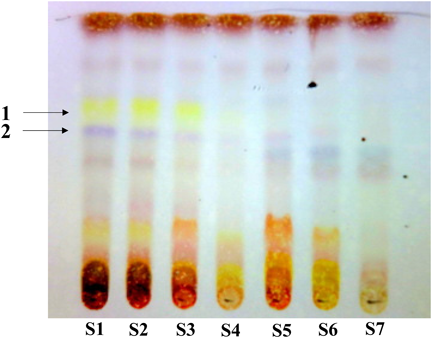

We collected the flower parts of M. kobus from the bud to fallen bloom stages and extracted them with MeOH to obtain the various extracts (Table 1). We examined the inhibitory activities for Con A-induced IL-2 production of each extract in murine splenic T cells and found that the inhibitory activities of the bud extracts were significantly more potent than those of the bloom extracts (Fig. 1(A)). Furthermore, extracts of S1, one of the bud stages, showed the strongest inhibitory activity and inhibited IL-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 1(B)). The chemical composition of each extract was analysed by HPTLC using CHCl3–MeOH (4 : 1, v/v), which showed a clearer pattern than other conditions. As a result, we found spots of 1 and 2 that are characteristic to the bud stage S1–S4 (Fig. 2); however, no significant differences were observed in the constituents with a wide range of polarity except with sugars that would not show the activity of in vitro assay used in this study. Thus, the IL-2 inhibitory activity of M. kobus was attributable to constituents characteristic to the bud stages. To identify compounds correspondent to spots 1 and 2, we attempted to separate the Magnolia Flower extract guided by TLC analysis for spots 1 and 2. The MeOH extract of Magnolia Flower was partitioned with ethyl acetate and water; then, each layer was separated to isolate tiliroside (1) and syringin (2) from the ethyl acetate and water layers respectively, as known compounds characteristic to bud stages (Fig. 3).

| Sample | Date | Developmental stages |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | Feb. 5, 2016 | Bud |

| S2 | Feb. 26, 2016 | Bud |

| S3 | Mar. 18, 2016 | Bud |

| S4 | Apr. 5, 2016 | Larger bud |

| S5 | Apr. 8, 2016 | One-third in bloom |

| S6 | Apr. 9, 2016 | Full bloom |

| S7 | Apr. 15, 2016 | Falling bloom |

Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

Development solvent; CHCl3–MeOH (4 : 1, v/v), detection; spraying with diluted sulphuric acid solution, followed by heating at 105°C. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

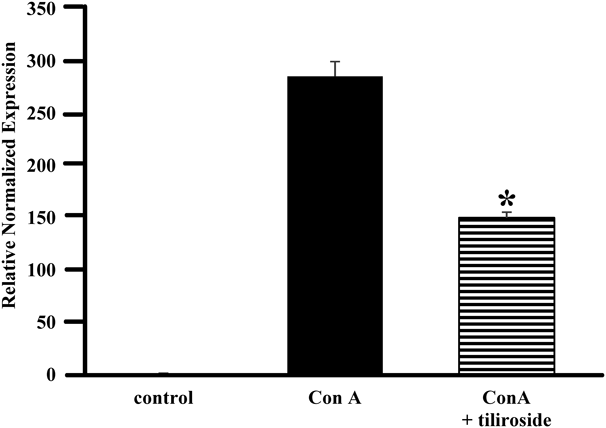

Furthermore, our examination of the inhibitory activities for Con A-induced IL-2 production of these constituents revealed that 1, but not 2, showed potent inhibitory activity against IL-2 production (Fig. 4). The inhibitory activity against T-cell receptor (TCR)-induced IL-2 production of 1 was comparable to those of Con A-induced IL-2 activity (Fig. 5(A)), whereas 2 did not show the activity (Fig. 5(B)). Song et al. reported that 2 is potentially antiarthritic agent,31) suggesting that 2 showed the anti-inflammatory effect by generating the aglycon in the process of digestion. Additionally, 1 significantly inhibited Con A-induced IL-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 6). Kaempferol, the aglycon of 1, also showed strong inhibitory activity against IL-2 production (Fig. 7(A)) and Con A-induced IL-2 mRNA expression (Fig. 7(B)), indicating that the aglycon part of 1 plays an important role in the inhibitory activity; however, the content of kaempferol was extremely small and could not explain the inhibitory activity of M. kobus upon comparative analysis with an authentic standard. Moreover, to investigate the inhibition of other cytokine, we measured inhibitory activities for IL-6 production of 1 and 2. These results showed that these compounds did not significantly show IL-6 inhibitory activity (data not shown), indicating that tiliroside (1) can specifically inhibited IL-2 production against IL-6 although further study will be needed to examine the effects of 1 on other cytokines. Collectively, these results indicate that the buds show higher inhibitory activity against IL-2 production and that the bud-derived compound tiliroside (1) can specifically inhibit Con A-induced IL-2 production and mRNA expression.

Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 4).

Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 4).

Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

Results are expressed as the mean ± S.E. (n = 3).

Magnolia kobus at the bud stages (S1–S4) inhibited IL-2 production; moreover, compound 1, a constituent characteristic to the bud stage, also showed this inhibitory effect. These results suggest that 1 plays an important role in the inhibitory activity of M. kobus. Nevertheless, the content of 1 is insufficient to explain the IL-2 inhibition exhibited by the extract in our semi-quantitative analysis. In fact, the HPTLC spot of 1 is light-coloured at S4 (late bud stage), further, Magnolia Flower as a commercially available crude drug inhibited stronger IL-2 production than M. kobus as preliminary test while the contents of 1 and 2 in Magnolia Flower were lower than those of in M. kobus, suggesting that a constituent other than tiliroside could be the active principle of M. kobus. Nguyen et al. have already reported that lignans from Magnolia flower show potent IL-2 inhibitory activity.19) However, despite that study reporting the identification of many IL-2 inhibitors, we were able to find the newly active constituent in M. kobus only by focusing on seasonal variation with TLC analysis.

In this paper, we report for the first time, to our knowledge, that buds of M. kobus have stronger inhibitory activity against IL-2 production than the opening blooms. Moreover, we found that tiliroside (1) and syringin (2) were seasonally variable constituents of M. kobus and that 1 inhibited IL-2 production in murine splenic T cells. This indicates that 1 could be the biologically active constituent influenced by seasonal changes in M. kobus buds. Generally, bioactivity-guided isolation is necessary to identify active constituents from crude drugs. However, this strategy needs considerable effort to ensure certainty and it is difficult to determine which HPLC peak or TLC spot is derived from the active constituent. Therefore, we were afraid that, under the guidance of the inhibitory activity, it was possible to isolate the same active compounds that have already been reported. However, we believe our methodological strategy examining the relationship between chemical compositions and biological activities during maturation could not only contribute to the scientific evaluation of medicinal parts of crude drugs but also assist in identifying biologically active constituents that have not yet been reported.

The 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR, and two-dimensional (2D)-NMR spectra of the samples dissolving CD3OD were recorded using a JUM-ECZ400S spectrometer (JEOL Co., Japan). Chemical shifts were expressed in δ (ppm), and tetramethyl silane was used as the reference standard. MS analyses were performed using the API 3200 LC-MS/MS (AB Sciex Pte. Ltd., Japan) and 910-MS FTMS (Varian, Inc., U.S.A.) systems.

MaterialsSeven samples of flower parts of M. kobus were collected from the International University of Health and Welfare from February to April 2016, and samples were dried and stored at 20°C. The details are shown in Table 1. For further species identification, portions of each sample were kept in the laboratory of the Tokyo University of Sciences as specimens. HPTLC and reverse-phase (RP)-TLC plates were purchased from Merck Company (U.S.A.). Syringin was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (U.S.A.). Kaempferol was purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Company Ltd. (Japan). Magnolia Flower (Lot. F350230) crude drug for isolation study was purchased from Uchida Wakanyaku Company (Japan).

HPTLC AnalysisSample PreparationEach sample (0.3 g) shown in Table 1 was powdered using the Wonder Crusher WC-3 (Osaka Chemical Co., Ltd., Japan) and then extracted with MeOH (100 mL) at room temperature for 12 h. The extract was filtered, and then evaporated under reduced pressure. Part of the dry extract (10 mg) was added to MeOH (1.0 mL), and then filtered through a 0.45 µm filter.

HPTLC Analysis of ExtractsEach M. kobus extract (10 mg/mL, 10 µL) was subjected to HPTLC; then, the plate was developed with a mixture of CHCl3–MeOH (4 : 1, v/v) until a distance of 7 cm was achieved. The plate was evenly sprayed with dilute sulphuric acid solution, followed by heating at 105°C for 10 min.

Extraction and IsolationMagnolia Flower (500 g) was extracted with MeOH (3 L × 2) at room temperature for 1 d to obtain the extract. The extract was suspended in water (H2O, 1 L), and then the solution was partitioned with ethyl acetate (1 L) to give two fractions [Fr. S, ethyl acetate layer, 54.2 g; Fr. W, H2O layer, 27.2 g]. Fr. S (54.2 g) was dissolved in CHCl3 (18 mL), and then the solution was applied to silica gel (ϕ 9.0 cm × 15 cm) eluted with CHCl3–MeOH system to give three fractions [Fr. A-1, CHCl3 (3 L) eluate; Fr. A-2, CHCl3: MeOH = 9 : 1 (3 L) eluate, 25.1 g; Fr. A-3, CHCl3–MeOH = 8 : 2 (3 L) and MeOH (1 L) eluate, 1.83 g]. Fr. A-3 (1.83 g) was dissolved in MeOH (14.5 mL), and then separated using Sephadex LH-20 (ϕ 4.5 cm × 41 cm, MeOH) to get four fractions [Fr. A-3-1, 1.03 g; Fr. A-3-2, 0.28 g; Fr. A-3-3, 0.48 g; Fr. A-3-4, 60 mg]. Fr. A-3-3 (0.48 g) was recrystallized from H2O to obtain 1 (302.4 mg).

Fr. W (27.2 g) was dissolved in H2O (40 mL), applied to MCI gel CHP20/P50 (ϕ 7.0 cm × 7.0 cm), and eluted using a H2O–MeOH system to obtain seven fractions [fr. 1, H2O eluate (600 mL), 12.6 g; fr. 2, 10% MeOH aq. eluate (400 mL), 1.08 g; fr. 3, 20% MeOH aq. eluate (400 mL), 507 mg; fr. 4, 30% MeOH aq. eluate (400 mL), 653 mg; fr. 5, 40% MeOH aq. eluate (400 mL), 1.15 g; fr. 6, 50% MeOH aq. eluate (400 mL), 811 mg; fr. 7, MeOH eluate (400 mL), 78.5 mg]. fr. 4 and 5 were combined as Fr. B (1.8 g), which was repeatedly separated using silica gel columns (CHCl3–MeOH), MCI gel CHP-20P/P120 (H2O–MeOH), and Sephadex LH-20 (MeOH) to obtain 2 (34.0 mg).

IL-2 and IL-6 Inhibitory ActivitiesBALB/c mice were treated and handled according to the Tokyo University of Science’s institutional ethical guidelines for animal experiments and with the approval of Tokyo University of Science’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permit number S18007) as described previously.24,33) We prepared culture supernatants of mouse splenic lymphocytes and measured the concentrations of IL-2 and IL-6 using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described previously.7,34)

Measurement of IL-2 mRNA ExpressionWe measured the IL-2 mRNA expression using real time RT-PCR as described previously.7,34)

StatisticsResults are expressed as the mean ± standard error (S.E.) The statistical significance of difference between two groups was calculated by unpaired Student’s t-test. The statistical significance of differences between positive control (Con A- or TCR-stimulated group) and other groups was calculated by using Dunnett’s test with the Instat version 3.0 statistical package (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). The criterion of significance was set at p < 0.05 (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, ### p < 0.0001).

This work was supported by The Research Foundation for Pharmaceutical Sciences.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.