2020 Volume 68 Issue 3 Pages 234-243

2020 Volume 68 Issue 3 Pages 234-243

Diphenhydramine, a sedating antihistamine, is an agonist of human bitter taste receptor 14 (hTAS2R14). Diphenhydramine hydrochloride (DPH) was used as a model bitter medicine to evaluate whether the umami dipeptides (Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp) and their constituent amino acids (Glu, Asp) could suppress its bitterness intensity, as measured by human gustatory sensation testing and using the artificial taste sensor. Various concentrated (0.001–5.0 mM) Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp significantly suppressed the taste sensor output of 0.5 mM DPH solution in a dose-dependent manner. The effect of umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids was tending to be ranked as follows, Asp-Asp > Glu-Glu >> Gly-Gly, and Asp > Glu >> Gly (control) respectively. Whereas human bitterness intensity of 0.5 mM DPH solution with various concentrated (0.5, 1.0, 1.5 mM) Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp all significantly reduced bitterness intensity of 0.5 mM DPH solution even though no statistical difference was observed among four substances. The taste sensor outputs and the human gustatory sensation test results showed a significant correlation. A surface plasmon resonance study using hTAS2R14 protein and these substances suggested that the affinity of Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp for hTAS2R14 protein was greater than that of Gly-Gly or Gly. The results of docking-simulation studies involving DPH, Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp with hTAS2R14, suggested that DPH is able to bind to a space near the binding position of Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp. In conclusion, the umami dipeptides Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp, and their constituent amino acids, can all efficiently suppress the bitterness of DPH.

Poor adherence is a big problem for national health services, as it leads to the reduced effectiveness of administered medicine with all the consequences thereof this is particularly important for geriatric1) and pediatric patients.2) In general, infants do not understand the need to take medicine regularly,3) may have difficulty swallowing medicine and be especially resistant to taking unpleasantly tasting medicine. As recommended in the European Medicines Agency (EMA) guideline, researchers should consider palatability at the preformulation stage of development of pediatric medicines.4) For pediatric patients over 2 years old, the simple suggestion to take pediatric medicines with vanilla-flavored ice-cream has been enthusiastically and widely adopted by parents.5)

As shown in our previous articles,6) the bitterness of orally available steroids can be suppressed by apple and orange juices and acidic sports drink, while the bitterness of macrolide dry syrup is dramatically enhanced in the presence of the same acidic drink or beverage, thus reducing adherence to the pediatric drug.7) In practice then, especially when taking individual patient preferences into account, it is difficult to determine the right bitterness-suppressing option for each pharmaceutical formulation.

Benecoat was developed as a bitter taste inhibitor by Katsuragi and Kurihara in Japan two decades ago in the food field.8) However, it was never actually used as it is a decomposed product of phospholipids, with a unique smell and taste, and was not acceptable to many patients, especially children.

Recently, it has been reported that umami dipeptides and related peptides may have an activating effect in the human brain.9) Kim et al. have also reported on the umami–bitterness interaction; in their study, they demonstrated that glutamyl dipeptides (umami dipeptides) inhibit a salicin-induced Ca2+ response,10) salicin being an agonist to hTAS2R16. In the present study, we have investigated bitterness inhibition by the umami dipeptides Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp, and their constituent amino acids Glu and Asp.

The bitter taste receptors provide a primitive alarm system that prevents the ingestion of potentially toxic food items in human.11,12) The bitter-responsive cells of taste buds located in the oral cavity express a subset of the 25 putatively functional human bitter taste receptors (hTAS2Rs)13–15) that are distantly related to the class A G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family.16) The functional characterization of hTAS2Rs has revealed that they can be grouped on the basis of their agonist spectra into broadly, narrowly, and intermediately tuned receptors.17) The three broadly tuned receptors are hTAS2R10,18) hTAS2R14,19) and hTAS2R46.20) Several in vitro studies have been reported, and heterologous expressions of hTAS2Rs for screening of bitter compound libraries have identified many compounds, including diphenhydramine hydrochloride (DPH), as agonists of hTAS2R14.21) However, even though 25 hTAS2Rs have already been identified, the specific hTAS2Rs for many bitter commercial medicines or substances have not yet been fully identified or characterized.

Previously, we evaluated the bitterness intensities of many commercial medicines using the taste sensor and confirmed our results by gustatory sensation testing.22–25) We demonstrated in a recent article that a specific taste sensor output (AN0) correlated well with the response of the bitter drug or substance to hTAS2R10 or hTAS2R14.26) In the present study, DPH, a widely used sedating antihistamine and known agonist of hTAS2R14, was used as a model bitter drug in the investigation of the bitterness-suppressing effects of the umami dipeptides Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp and their component amino acids,27–29) using both the taste sensor and human gustatory sensation testing. The relative affinities of the umami dipeptides and their component amino acids for hTAS2R14 protein were examined using surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

Finally, a docking-simulation study was performed involving DPH, Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp with hTAS2R14, to examine potential binding sites for DPH.

Diphenhydramine hydrochloride, L-Glutamic acid and L-Aspartic acid, were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Japan. Glycine was purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Japan. L-Glutamyl-L-glutamic acid, L-Aspartyl-L-aspartic acid were purchased from Bachem AG. Glycyl-glycine was purchased from Peptide Laboratories, Japan. All reagents were special grade.

Sensor MeasurementTaste sensor SA402B (Intelligent Sensor Technology Inc., Atsugi, Japan) was used in this study. The detecting sensor part of the equipment consists of a reference electrode and a taste sensor or working electrode (AN0), composed of a lipid/polymer membrane (phosphoric acid di-n-decyl ester/dioctyl-phosphonate). The measurement procedure was as follows. The working electrode was dipped into the reference solution and the electric potential obtained (mV) was defined as Vr0. Then the working electrode was dipped into a sample solution and the electric potential obtained was defined as Vs. The working electrode was then rinsed with reference solution. When the working electrode was dipped into fresh reference solution, the potential of the reference solution was defined as Vr1. The difference between the potentials of the reference solution before and after sample measurement (Vr1−Vr0) was defined as ‘Change in the membrane Potential caused by Adsorption’ (CPA), a specific expression of bitterness. In this study, the CPA of AN0 was used to evaluate the bitterness of DPH.30)

DPH solutions at concentrations of 0.03, 0.05, 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 mM were prepared with distilled water. DPH solutions (0.5 mM) containing various concentrations (0.001, 0.01, 0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 mM) of Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu, Asp and 0.5 mM amino acids (asparagine, alanine, arginine, isoleucine, glutamine, cysteine, serine, tyrosine, tryptophan, threonine, valine, histidine, phenylalanine, methionine, lysine, leucine, proline) were prepared as sensor samples.

Human Gustatory Sensation TestingHuman gustatory sensation tests were approved in advance by Mukogawa Women’s University Ethics Committee No. 17–54, which is compliant with the ‘World Medical Association Helsinki Declaration’ and ‘Ethics Guidelines on Medical Research for Humans’ (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology; Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan).

Gustatory sensation testing to measure bitterness intensity was performed with seven well-trained female volunteers according to a modification of a previously described method. No subject reported having a cold or other respiratory tract infection in the week prior to testing. The subjects were asked to refrain from eating, drinking, or chewing gum for at least 1 h prior to testing. All subjects were non-smokers and signed an informed consent before the experiments.

The gustatory sensation test was carried out as follows: quinine hydrochloride solutions at concentrations of 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 mM were prepared as bitterness standards. Bitterness intensities (τ) of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 were allocated to these increasing concentrations of the standard solution. Before testing the samples, the volunteers were asked to keep 2 mL of each standard quinine hydrochloride solution in their mouths for 5 s and were told the concentration and bitterness intensity of each solution.

Sample solutions containing 0.5 mM DPH solution were prepared with each dipeptide or peptide at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mM. This study was conducted in a single blind study. In each test, the volunteers were asked to keep 2 mL of sample solution in their mouths for 5 s and to evaluate the sample’s bitterness scores.

After tasting each standard and sample solution, subjects gargled well and waited for at least 20 min before tasting the next sample.

SPR Measurement and AnalysisThe interactions between hTAS2R14 protein and DPH, dipeptides (Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp and Gly-Gly) or amino acids (Glu, Asp and Gly) were evaluated by SPR analysis using SPR-Navi 200 (BioNavis, Finland).31,32)

For immobilization of hTAS2R14 recombinant protein (hTAS2R14 protein) (Abnova, Taiwan) on a gold-coated SPR sensor chip, a modification of the method described by Solanski et al. was used.33)

Prior to functionalization, a gold-coated SPR sensor chip, precleaned with ethanol and ultrapure water, was submerged in piranha solution (1 mL 30% hydrogen peroxide water +3 mL sulfuric acid) for 10 min. The chip was then removed and rinsed with ultrapure water. A self-assembled monolayer (SAM) of 11-amino-1-undecanethiol hydrochloride (AUT) was formed by immersion of the gold-coated chip into a 1 mM ethanol solution of AUT for 24 h at room temperature. The SAM(AUT)-modified gold chip was rinsed with ethanol and ultrapure water several times and dried under a steam of nitrogen before being dipped in 0.1% glutaraldehyde for about 2 h, after which it was washed thoroughly with ultrapure water. hTAS2R14 protein (0.5 µg) was immobilized onto the glutaraldehyde-modified SAM (AUT) gold chip by adding several drops (50 µL) of hTAS2R14 (10 µg/mL) solution to 50 mm2 area of the gold chip and incubating for about 12 h at room temperature.

After incubation, unbound hTAS2R14 was removed by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) which had been kept at 4°C. A flow rate of 50 µL/min was used throughout the experiment and all experiments were performed at a constant temperature of 20°C.

The SPR sensograms were obtained by measuring changes in the SPR angle during the injection of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10 mM solutions of DPH, dipeptides (Gly-Gly, Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp) or amino acids (Gly, Glu, Asp) over the hTAS2R14–SAM (AUT)-gold-coated SPR sensor chip. SPR kinetic analysis of the results was performed with TraceDrawer 1.6 from BioNavis. Each sample was referenced using a blank reference channel on-line; blank samples were also measured and referenced from all sensograms during data analysis.32) The sensograms were fitted with one-to-one models in the TraceDrawer software. The one-to-one interaction model is described as follows.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Where Y is the recorded signal, c is the concentration of ligand in the bulk liquid in formula 1, ka is the association rate constant, kd is the dissociation rate constant, and KD is the dissociation constant.

Molecular Modeling and Ligand Docking SimulationsThe hTAS2R14 model was built on the basis of the solved structure of human CC chemokine receptor type 9 (CCR9; pdb code: 5lwe), which was found in the BLAST database as the highest scored structure among all proteins solved their structure. CCR9 showed a well-conserved amino acid sequence (22% for identity and 44% for similarity) with that of hTAS2R14. Initially, the amino acids of CCR9 were replaced by those of hTAS2R14; the predicted structure of hTAS2R14 was then refined and minimized in energy using the Prime module in Schrödinger suite (ver. 10.3). The generated structure of hTAS2R14 was prepared for ligand docking using the Protein Preparation Wizard. A grid area was generated to the extracellular site of the receptor for ligand docking. The chemical structures of DPH, Glu, Glu-Glu, Asp and Asp-Asp were drawn using ChemDraw software, and three-dimensional properties were applied using the LigPrep module. The prepared ligands were also protonated in the condition pH 7.0 ± 0.5; the optimized ligands were then docked into the built structure of hTAS2R14 using Glide module in SP mode. Finally, the positions of the docked ligands were scored via the Glide module, and the docking structures illustrated with a molecular visualizing software, PyMOL (Schrödinger).

Statistical AnalysisExcel–Toukei 2010 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Japan) was used for statistical analysis. Dunnet test and Tukey test were used for multiple comparisons. Correlation between taste sensor output value and bitterness intensity scores from human gustatory sensation tests were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation test. Correlations between the inhibition ratio of taste sensor output and parameters ka, kd and KD were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation tests. The 5% level of probability was considered significant.

The output of sensor AN0 (CPA) for different concentrations of DPH (0.03, 0.05, 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 mM) was shown in Fig. 1. The sensor output in response to these DPH solutions increased in a dose-dependent manner. It was suggested that bitterness of DPH would be evaluated by using this AN0 (CPA) value.

Concentration of DPH was 0.03, 0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 0.5 mM, respectively.

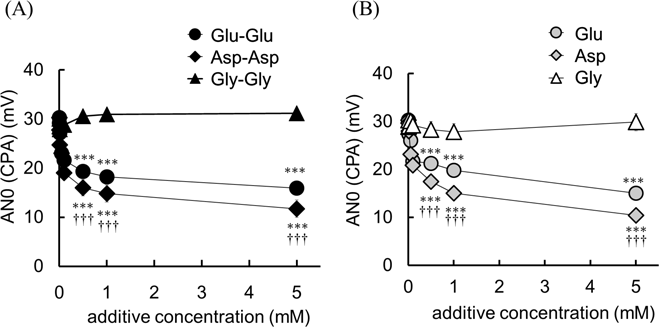

Figure 2(A) shows the taste sensor outputs in response to 0.5 mM DPH containing various concentrations (0.001–5.0 mM) of Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp and Gly-Gly, respectively. The addition of Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp significantly inhibited the sensor output of DPH in a dose-dependent manner. The addition of Gly-Gly had no effect on the sensor output. These results suggested Glu-Glu or Asp-Asp would suppress the bitterness of DPH but Gly-Gly would not.

(A) n = 3, mean ± S.D., *** p < 0.001 vs. Gly-Gly, ††† p < 0.001 vs. Glu-Glu (Tukey test). (B) n =3, mean ± S.D., *** p < 0.001 vs. Gly, ††† p < 0.001 vs. Glu (Tukey test).

Figure 2(B) shows the taste sensor output in response to 0.5 mM DPH containing various concentrations (0.001–5.0 mM) of Glu, Asp and Gly (control), respectively. The addition of Glu or Asp significantly inhibited the sensor output of DPH in a dose-dependent manner. The addition of Gly had no effect on the sensor output.

In human gustatory sensation tests, the addition of Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp (0.5, 1.0 and 5.0 mM) significantly inhibited the bitterness of 0.5 mM DPH (Figs. 3(A), (B), (D), (E)); no such change was observed with Gly-Gly or Gly (Figs. 3(C) and (E)).

n = 7 mean ± S.D., *** p < 0.001 vs. 0 mM; ††† p < 0.001 vs. 0.5 mM (Tukey test).

In this study, CPA which means adsorption of substances to the lipid membrane, was used as taste sensor output. DPH caused CPA as shown in Fig. 1. Electric charged amino acids did not cause CPA, but they caused lipid membrane potential when the membrane (taste sensor) was dipped in sample solution. This means that adsorption of electric amino acids to lipid membrane were lost by washing with reference solution. Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp also caused lipid membrane potential when the membrane was dipped in sample solution, but Gly-Gly did not. From these results, the inhibition the taste sensor output of DPH by addition of Glu-Glu or Asp-Asp would be caused by adsorption of Glu-Glu or Asp-Asp to lipid membrane in competition with DPH when the taste sensor was in sample solution. On the other hand, little adsorption of Gly-Gly to lipid membrane might the reason why the adsorption of DPH to lipid membrane was not inhibited by Gly-Gly.

From the tukey tests, the bitterness suppressing effect of umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids could be ranked as follows, Asp-Asp > Glu-Glu >> Gly-Gly, and Asp > Glu >> Gly, respectively.

Kurihara et al. have revealed that in general bitterness drugs have a positive charge and that seemed an important factor in bitterness perception.34,35) The measurement of bitterness by a taste sensor mimics the human taste receptor based on the principle that the bitterness drug neutralizes the membrane potential by hydrophobic interaction with the charged sensor membrane.30) Umami peptides and amino acids used in the present study were acidic, DPH is a basic drug, Asp-Asp and Glu-Glu have a negative charge, and Gly-Gly has no charge. Umami peptide (Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp) having three carboxy groups has higher acidity than the amino acid (Glu, Asp) having two carboxy groups, the umami peptides seem to restrict sensor output of basic molecule DPH more efficiently rather than constituted amino acids. In our previous articles,36,37) larger value of relative value whereas small value of amino acid solutions in related to branched chained amino acids. Also in this study, as a result of this experiment, the AN0 (CPA) values of 0.5 mM Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp solution were less than 1.0 mV (−1.09, −0.78, −0.82 and 0.37 mV, respectively).

As shown in Figs. 3(A) and (B), it can be seen that the umami peptide can suppress the bitter taste of DPH in a dose-dependently as in the taste sensor measurement. Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp can suppress bitterness especially at a high concentration of 5.0 mM. In general, there are three types of taste cell of the taste bud: type I, type II, and type III.38) Taste cells that accept bitterness are classified as type II cells. Recently, it has been reported that this type II cell is related not only to bitter taste acceptance but also to sweetness and umami taste acceptance.38,39) Therefore, high concentration solution of Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp suppresses the bitter taste of DPH. The Influence of Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp on umami receptors is not clear, but it cannot be denied that umami receptor would be interact with bitterness suppression.

As shown in Figs. 3(B) and (E), Asp-Asp tended to show a bitterness-inhibiting effect even at a lower concentration rather than the Asp solution, which is a constituent amino acid, but there was no statistically significant difference in the bitterness-inhibiting effect between the umami peptide and the amino acid alone. Nowadays, sodium glutamate is used as a bitterness inhibitor of morphine water.40) In the present study, Asp-Asp and Glu-Glu can be expected to have a bitter taste-suppressing effect superior to agonists of hTAS2R14 such as DPH rather than Asp and Glu alone solutions. Nevertheless, it can be considered that the bitterness suppression corresponding to the umami peptide can be achieved by adjusting the appropriate concentration of amino acid alone. While as reported by Kim et al., it is noted in the paper that the 5-residue umami peptide has a bitterness suppressant effect. Furthermore, there has another advantage in that the peptide has recently been reported to have an improvement effect on human brain function.41,42)

In similar experiments, a further 17 amino acids (asparagine, alanine, arginine, isoleucine, glutamine, cysteine, serine, tyrosine, tryptophan, threonine, valine, histidine, phenylalanine, methionine, lysine, leucine, proline) have been shown not to reduce the sensor output of 0.5 mM DPH. Figure S1 shows taste sensor (AN0) output (CPA) of 0.5 mM DPH and taste sensor output of 0.5 mM 17 kind of amino acid mixed with 0.5 mM DPH. As a result, it was found that the 17-amino acid were suggested to have no bitterness-suppressing effect. Arg, His, and Lys were typical basic amino acids and have positively charged in solution. therefore, the addition of those amino acids seemed apparently increase the sensor output (CPA).

A preparation in which Monosodium glutamate suppresses the bitter taste of morphine water is commercially available.40) Previous studies have reported the bitterness-inhibiting effect of Glu-Glu in sensory tests.43)

It has previously been reported that Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu and Asp taste of umami and sourness.44) Recently, the umami taste was reported to affect the transduction of the taste of bitterness.45) This supports our contention that the umami taste of these dipeptides and their constituents will be particularly useful in bitterness suppression for various type of bitter medicine.

Correlation between Taste Sensor Output Value and Bitterness Intensity Scores from Human Gustatory Sensation TestsFigure 4(A) presents data from DPH solution samples (n = 10) containing three dipeptides (Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Gly-Gly) at different concentrations. The bitterness sensor output value (AN0 (CPA) in mV) is plotted on the horizontal axis and the bitterness intensity (τ) from human gustatory sensation tests on the vertical axis. A statistically significant correlation was found (Spearman’s correlation coefficient = 0.817).

(A) Diphenhydramine hydrochloride (DPH) solutions containing three dipeptide solutions at different concentrations. (n = 10, rs = 0.817, p < 0.01 Spearman’s correlation test) (B) DPH solutions containing three amino acid solutions at different concentrations. (n = 10, rs = 0.970, p < 0.001 Spearman’s correlation test)

Figure 4(B) presents data from DPH solution samples (n = 10) containing three different amino acid solutions (Glu, Asp, Gly) at different concentrations. The bitter taste sensor output value (mV) is plotted on the horizontal axis and the bitterness intensity (τ) from human gustatory sensation tests on the vertical axis. A statistically significant correlation was observed (Spearman’s correlation coefficient = 0.970).

Therefore, the bitterness-suppressing effects of both the umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids using the taste sensor and in human taste tests are highly correlated.

SPR MeasurementsSPR spectra of the pure SPR sensor surface and the same sensor surface after depositing SAM (AUT)-bound hTAS2R14 on the sensor, are shown in Figs. 5(A), (B) and (C). If 1 ng of substance binds to 1 mm2, it shifts 0.1 degree of angle of the portion where the reflected light intensity decreases.46) The clear shift of 0.432 degrees (67.835 ± 0.012 to 68.267 ± 0.010) of the SPR peak position corresponds to a mass surface density of about 431.7 ng/cm2 of AUT on the sensor membrane. Also, the clear shift of 1.0767 degrees (68.267 ± 0.010 to 69.343 ± 0.02) of the SPR peak position corresponds to a mass surface density of about 1076.66 ng/cm2 of hTAS2R14 and AUT on the sensor membrane. The shift of approximately 1 degree means 10 ng of hTAS2R14 protein bound to 1 mm2 area of gold chip. Consequently, almost all (0.5 µg/50 mm2) of hTAS2R14 was suggested to be immobilized to AUT modified gold chip, and that therefore this model can be used to evaluate the interaction between hTAS2R14 and other substances such as amino acids or dipeptides.

n = 6, mean ± S.D., *** p < 0.001 vs. gold only ††† p < 0.001 vs. AUT (Tukey test).

Figure 6 shows the real-time SPR signal response caused by the interaction between hTAS2R14 protein and 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 and 10 mM DPH, dipeptides (Gly-Gly, Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp) or amino acids (Gly, Glu, Asp). All seven substances responded in a dose-dependent manner. The kinetic fitting by TraceDrawer provided the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd) and dissociation constant (KD) for each interaction.

(A) DPH (diphenhydramine hydrochloride), (B) Gly-Gly, (C) Glu-Glu, (D) Asp-Asp, (E) Gly, (F) Glu, (G) Asp.

Figure 7 is a two-dimensional map (on-off rate map) obtained by plotting ka and kd obtained in the measurement of intermolecular interactions between hTAS2R14 and DPH, umami peptide, and constituent amino acids. The logarithmic value of ka is shown on the horizontal axis, and the larger the ka, the faster the binding of DPH, umami peptide and constituent amino acid to hTAS2R14. The vertical axis shows the value of kd, and the larger the kd, the slower the dissociation. The results showed that umami peptides (Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp) and constituent amino acids (Glu, Asp) bind faster to hTAS2R14 and dissociate slower than DPH. Gly-Gly and Gly have a faster binding rate than DPH, but a faster dissociation rate. This suggests that Gly-Gly and Gly could not inhibit the binding of DPH to hTAS2R14.

Figure 8 shows correlation between the inhibition ratio (%) of the taste sensor output (the ratio of the sensor output of DPH alone to that of DPH plus the dipeptides or amino acids (5.0 mM)) and parameters (ka, kd and KD) from the interaction of hTAS2R14 protein with the dipeptides and amino acids. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs) for the correlation between the bitterness inhibition ratios (%) and parameters ka, kd and KD, were 0.82857, −0.4928 and −0.4857, respectively. The parameter ka significantly correlated with the bitterness inhibition ratio (p < 0.01). This result indicates that potent association constants between hTAS2R14 and the umami peptides and amino acids are responsible for suppressing the bitterness of DPH. The bitterness inhibition ratio showed good correlation with ka but not with kd. This indicates that the association between hTAS2R14 and umami peptides or amino acids has a greater influence on bitterness inhibition than their dissociation.

In order to predict binding sites for DPH and dipeptides, we built a model structure of hTAS2R14 based on the solved structure of human CCR9. Subsequently, we performed docking simulations on hTAS2R14 with DPH, Asp-Asp and Glu-Glu. Although five structures with each ligand were emerged, the most stable ones were selected and analyzed further in detail. Since the distance of 4 Å from the docked ligands could be interactive ranges by taking flexibilities into account, several amino acids were selected in simulated structures, respectively (Fig. 9). First, the DPH docked structure showed F47, S55, W119, and I122 for either hydrophobic or electrostatic interaction (Fig. 9A), electrostatic interactions generally being more potent than hydrophobic interactions. Second, possibilities of electrostatic interactions with N123, Y270, S274, Y302 and Q296 and a feasible hydrophobic interaction with W119 were proposed to docked Asp-Asp in the simulated structure (Fig. 9B). The amino acids were common in the Glu-Glu docked structure in a similar manner to Asp-Asp (Fig. 9C). The distances between each amino acid and the docked ligands were summarized in Table 1.

The simulated structures are represented in a ribbon model. The docked ligands, DPH, Asp-Asp and Glu-Glu are shown as stick models with yellow, green and cyan, respectively, for carbon; nitrogen and oxygen are colored in blue and red, respectively. The dashed lines indicate possible interactions between ligands and amino acids (magenta for electrostatic interactions, purple for hydrophobic interactions). The tagged amino acids in close proximity to the ligands are also shown in the stick model using gray for carbons. The structures are shown as viewed from the membrane (left) and extracellular space (right).

| DPH | Asp-Asp | Glu-Glu | |

|---|---|---|---|

| F47 | 3.8 | — | — |

| S55 | 2.9 | — | — |

| W119 | 3.9 | — | — |

| I122 | 4.0 | — | — |

| N123 | — | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Y270 | — | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| S274 | — | 3.1 | 3.4 |

| Q296 | — | 3.3 | 2.7 |

| Y302 | — | 2.8 | 3.0 |

Diphenhydramine hydrochloride = DPH.

Although other interactions including hydrogen bonds via undefined water molecules were still remains, these results implied that DPH binds to a space near to the positions for Asp-Asp and Glu-Glu. In general, electrostatic interaction is potent compared to hydrophobic interaction. The amount of possible electrostatic interaction bonds between Asp-Asp (or Glu-Glu) and hTAS2R14 was more than that in DPH docked structure.

Previously, several computational studies had been performed on partial monomeric structures of TAS2R10, TAS2R14 and TAS2R46 with their respective agonists.47–50) Prior to our docking simulations on hTAS2R14, we explored appropriate formations under physiological conditions. However, the physiological and pharmacological significances of oligomerization of the receptor were not obvious. Kuhn et al. showed that hTAS2Rs formed oligomers in vitro.47) However, oligomerization of the receptors in vivo is impracticable due to the lack of specific antibodies for hTAS2Rs and limited availability of human tissue samples. Thus, in this study, a monomeric hTAS2R14 model was built and applied to docking simulations with feasible agonists.

In order to clarify the mechanism behind bitterness masking by Asp or Glu, we performed docking simulations of hTAS2R14 with each amino acid. However, the simulations encountered various problems due to the small molecular weights involved, making the docking positions of Asp or Glu with hTAS2R14 hard to designate.

Advantages of Using Umami Dipeptides and Constituent Amino AcidsCyclodextrin plays an important role as a molecule to suppress chemical bitterness masking and has been used as an inclusion complex useful for improving formulation properties. For example, it was incorporated in Prostaglandin E1 injection, itraconazole oral solution, cetirizine hydrochloride OD tablet product, respectively.51–53) On the other hand, theoretically, it is difficult to make the free drug concentration near zero level by usage of cyclodextrin because complex formation is performed by inclusion via equilibrium. Usually, an excessive amount of cyclodextrin relative to the amount of drug is considered necessary to suppress bitterness. In addition, the limited size of bitter medicines should be included.54,55) Cyclodextrins also have been reported to cause gastrointestinal disorders as a side effect.51) However, as mentioned above, there is a report56) that cetirizine has been able to suppress bitterness to some extent using cyclodextrin.

On the other hand, amino acids and umami peptide seemed safely available for a wide range of drugs. Sodium glutamate is already used as a pharmaceutical additive in commercial oral liquid formulation containing morphine. Therefore, the addition of Asp and Glu in the solid preparation might be choice. The application of umami peptides or related amino acid can be expected to have bitterness masking at high concentrations via umami receptor57) and improve brain function.41,42)

Applications of Umami Dipeptides and Their Constituent Amino Acids in Pediatric MedicineIn this study, the taste sensor and human gustatory test results have shown that the umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids can efficiently suppress the bitter taste of DPH. Using SPR analysis and docking simulations of the molecular model, the affinity between the bitter taste receptor hTAS2R14 and the umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids was shown to be high.

A search of BitterDB (http://bitterdb.agri.huji.ac.il/dbbitter.php), a database of bitter-tasting substances, reveals many substances which are ligands for hTAS2R14 (for example, caffeine, chlorpheniramine, diphenidol, flufenamic acid, haloperidol, noscapine and papaverine).26)

Docking simulation between DPH, Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp and hTAS2R14 suggested that DPH is most likely to bind to a space near the binding position of Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp. This indicates the mechanism by which Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp can suppress the bitter taste of medicines that are hTAS2R14 ligands.

Thus, although the detailed mechanism behind the bitterness-suppressing effects of the umami dipeptides and their constituent amino acids has not been completely clarified, it can be predicted that they would suppress the bitterness of pharmaceutical active ingredients that are ligands of hTAS2R14.

Kim et al.,10) reported that not only two residue but also five residue umami peptides have been confirmed to inhibit intracellular calcium in hTAS2R16 experiments. In addition, neurotransmission-related interaction between umami and bitterness has also been reported.38) Moreover, sodium glutamate is already used as a bitterness inhibitor in commercial product of orally liquid preparation.40) Nevertheless several problems (e.g. stability) still remain to be improved more or less, the use of umami peptides or amino acids for bitterness masking is considered to be effective.

Although some pediatric drugs are sweetened and taste-masked, prolonged sweetness exposure is considered to adversely affect taste formation during the developmental stages.58) The tastes of dipeptides Glu-Glu and Asp-Asp are characterized by slight acidity and low umami. It is considered that the Glu-Glu, Asp-Asp, Glu, and Asp are likely to be successful when used as bitterness-suppressing additives in pediatric medicines.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP16K08425, JP16K08426.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The online version of this article contains supplementary materials.