2020 年 68 巻 3 号 p. 244-250

2020 年 68 巻 3 号 p. 244-250

Aspidosperma alkaloids, a subclass of monoterpenoid indole alkaloids rich in the Apocynaceae plants, possess remarkable antitumor activities, but the underlying mechanisms have rarely been reported. In the current project, 11-methoxytabersonine (11-MT), an aspidosperma-type alkaloid isolated from Tabernaemontana bovina, significantly inhibited the viability of two human lung cancer cell lines A549 and H157, and the molecular mechanisms were thus investigated. The results showed that 11-MT killed lung cancer cells via induction of necroptosis in an apoptosis-independent manner. In addition, 11-MT strongly induced autophagy in the two cell lines, which played a protective role against 11-MT-induced necroptosis. Finally, the autophagy caused by 11-MT was found to be via activation of the AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) and the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathways in both cells. Taken together, 11-MT exhibited an antitumor mechanism different from that of previously reported analogues and could have the potential to serve as a lead compound for the development of new chemotherapy for lung cancer.

Lung cancer is gaining more and more attention in recent years for the rapidly increasing incidence and mortality. Investigators have been searching for new chemotherapies including those of natural origin that could interfere with the development and progress of lung cancer.1) A considerable portion of clinical anticancer drugs in the market are natural products (NPs) or are developed from NP pharmacophores.2,3) Monoterpenoid indole alkaloids (MIAs) are a very important family of NPs that have been well known for their anticancer activities. For example, vincristine has long been used as a first-line antitumor drug.

Aspidosperma alkaloids are a major subclass of MIAs produced mainly by plants of the Apocynaceae family. Previous reports have indicated that these alkaloids possess significant cytotoxicity against different types of cancer cells, including human leukemia, lung, colon and breast cancer cells.4–6) In our recent phytochemical investigation on the roots of Tabernaemontana bovina Lour. (Supplementary Materials (SM)), 11 MIAs were isolated and identified. By screening the anti-proliferative activities of these MIAs against two human lung cancer cell lines A549 and H157, we found that an aspidosperma alkaloid named 11-methoxytabersonine (11-MT) significantly inhibited the cell viability. Although literature reports have demonstrated that 11-MT exerted remarkable cytotoxic effects against a panel of cancer cell lines, the detailed molecular mechanisms remain unclear.4) Previous studies revealed that two analogues (jerantinines A and B) of 11-MT induced remarkable apoptosis in a variety of human cancer cells.7,8) Although 11-MT differed from the former two alkaloids only in the absence of 10-OH group, a preliminary study by us on the potential mechanism of 11-MT toward A549 and H157 cells suggested a different mode of action.

Another type of regulated cell death is necroptosis, and in contrast to apoptosis, necroptosis is independent of caspase activity. Recent studies have suggested that necroptosis can be invoked in certain cancer cells by chemotherapeutics,9) such as obatoclax mesylate, quercetin and Smac mimetics. Furthermore, some studies demonstrated that under the condition of the pharmacological inhibitor or genetic ablation of apoptosis related genes, necroptosis was activated as an alternative cell death for apoptotic pathway, making it promising target in apoptotic resistance cells.10,11)

Macroautophagy (from hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a self-degradation process, in which unnecessary or damaged material are sequestered in double-membrane vesicles termed autophagosomes and delivered to lysosome. There, the sequestered cargoes in autophagosomes are degraded and recycled. Thus, autophagy is crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and plays a prosurvival role.12,13) In other cases, autophagy can induce a prodeath signal pathway.14) Therefore, autophaghy can determine cell fate.

Our investigations showed that 11-MT induced necroptosis instead of apoptosis in the two cell lines, while it simultaneously caused autophagy which mediated a cytoprotective effect. Further work on the mechanism of autophagy induction revealed that 11-MT promoted both AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK) activity resulting in mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activity in the two cancer cells. Details of these studies were described in this paper.

Two human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines, A549 and H157, were used to examine the effects of the 11 natural MIAs on cell survival by the SRB (sulforhodamine B) method. The cancer cells were first incubated with the tested alkaloids (Fig. S1, SM) at 5 µM for 48 h. The assay results showed that 11-MT (4) significantly inhibited A549 and H157 cell growth while other compounds did not exhibit obvious inhibition against both cell lines (Fig. S1a, SM). 11-MT (structure shown in Fig. S1b, SM) was then chosen for further investigation. Cell viability upon 11-MT treatment was evaluated in a concentration-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 2.675 and 2.018 µM for A549 and H157 cells, respectively (Fig. S1c, SM). The morphological changes revealed that some cells became round and detached from the substratum when treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for different period of time (Fig. S1d, SM).

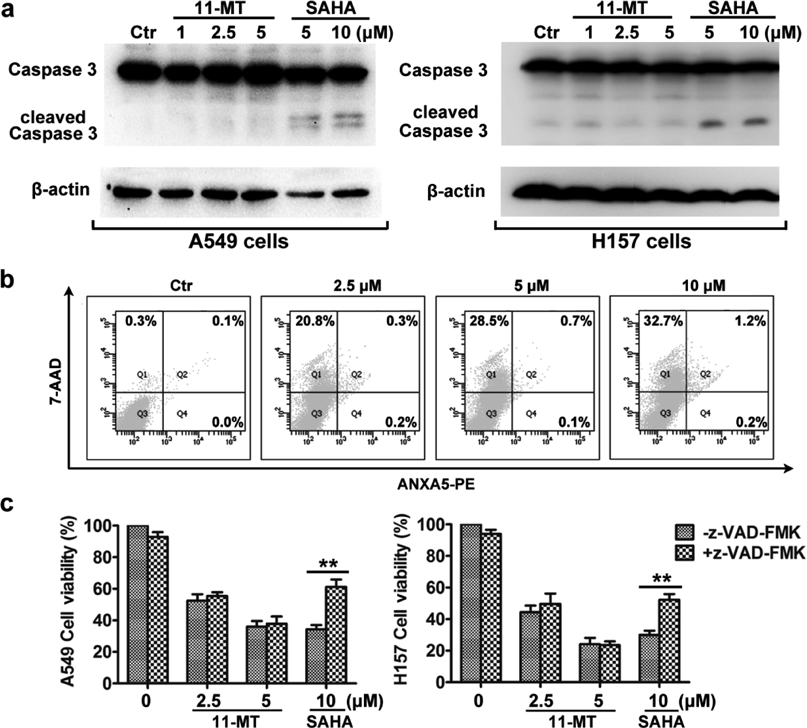

As apoptosis is one of the major mechanisms involved in chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity,15) a series of experiments detecting apoptosis were subsequently conducted. Interestingly, we found that the cell death induced by 11-MT was not via apoptosis. The evidences included no detectable activation of caspase 3 (Fig. 1a), as well as no induction of both early and late apoptosis by Annexin V-PE/7-Aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining and flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 1b). In addition, apoptosis blocking by the pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-FMK had no suppression on 11-MT-induced cell death, whereas suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA) induced cytotoxicity was significantly suppressed (Fig. 1c, SAHA as a positive control here).16)

(a) A549 and H157 cells were treated with the given concentrations of 11-MT for 48 h. The cleaved caspase 3 was detected by Western blot. β-Actin was used as an input control. Cells treated with 5 and 10 µM SAHA (Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, trade name: vorinostat) for 48 h were used as a positive control of apoptotic cell death. (b) A549 cells were treated with 11-MT for 48 h with indicated concentrations and were stained with ANXA5-PE/7-AAD. Flow cytometry was used to analyze the apoptotic cells. (c) Cells were pretreated with the z-VAD-FMK (5 µM) for 1 h and then exposed with given concentrations of 11-MT or SAHA (10 µM) for an additional 48 h. Cell viability was measured by SRB assay. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3.

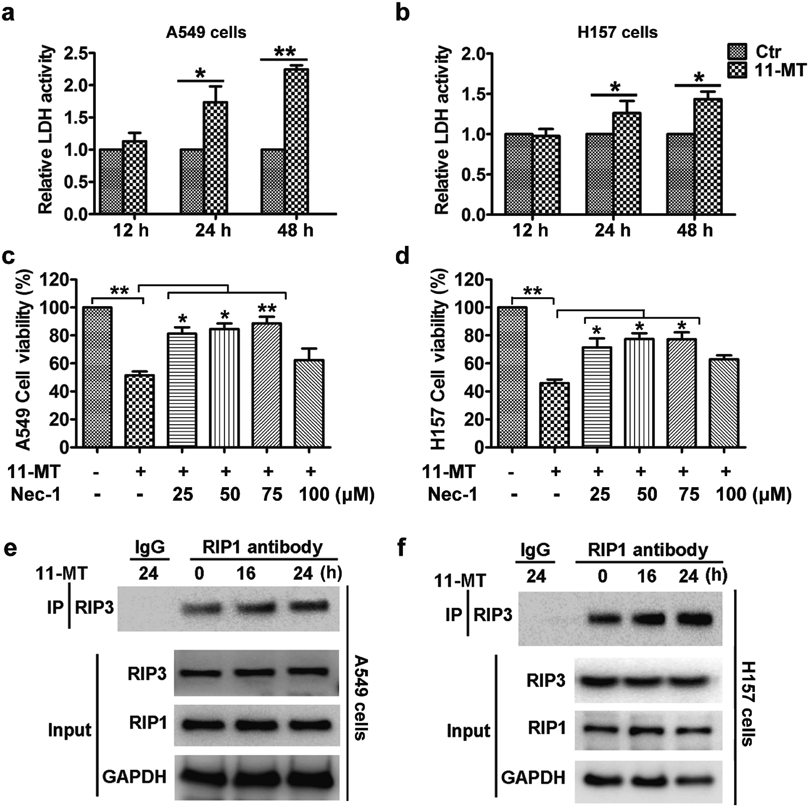

Since 11-MT-induced cell death was mainly non-apoptotic, we further examined the effect of 11-MT on lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. The results demonstrated that 11-MT promoted the release of cellular LDH in both A549 and H157 cells (Figs. 2a, b). Moreover, 11-MT-induced cytotoxicity was effectively prevented by the receptor-interacting serine/threonine kinase 1 (RIP1) inhibitor necrostatin-1 (Figs. 2c, d). Thus, cell death resulting from 11-MT was RIP1-dependent. The formation of necrosome, which is controlled by phosphorylation and assembly of the RIP1–RIP3 complex, is an important hallmark of activation of necroptosis.17) We thus further investigated the effect of 11-MT on the interaction of RIP1 with RIP3 using immunoprecipitation method. As shown in Figs. 2e and f, 11-MT enhanced the interactions of RIP1 with RIP3 in both A549 and H157 cells. Our results indicated that the formation of necrosome was increased by treatment with 11-MT. Therefore, the cytotoxicity of 11-MT toward NSCLS cells was through necroptosis.

(a,b) A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for indicated times. Cell death was measured by LDH release assay. (c, d) A549 and H157 cells were pretreated with the given concentrations of necrostatin-1 (Nec-1) for 1 h and then treated with 11-MT (2.5 µM) for an additional 48 h. Cytotoxicity was detected by SRB assay. (e,f) A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for indicated times. The proteins were analyzed by Western blot after immunoprecipitation with an anti-RIP1 antibody. Rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) was used as a negative control. RIP1 and RIP3 were detected by immunoblotting. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3.

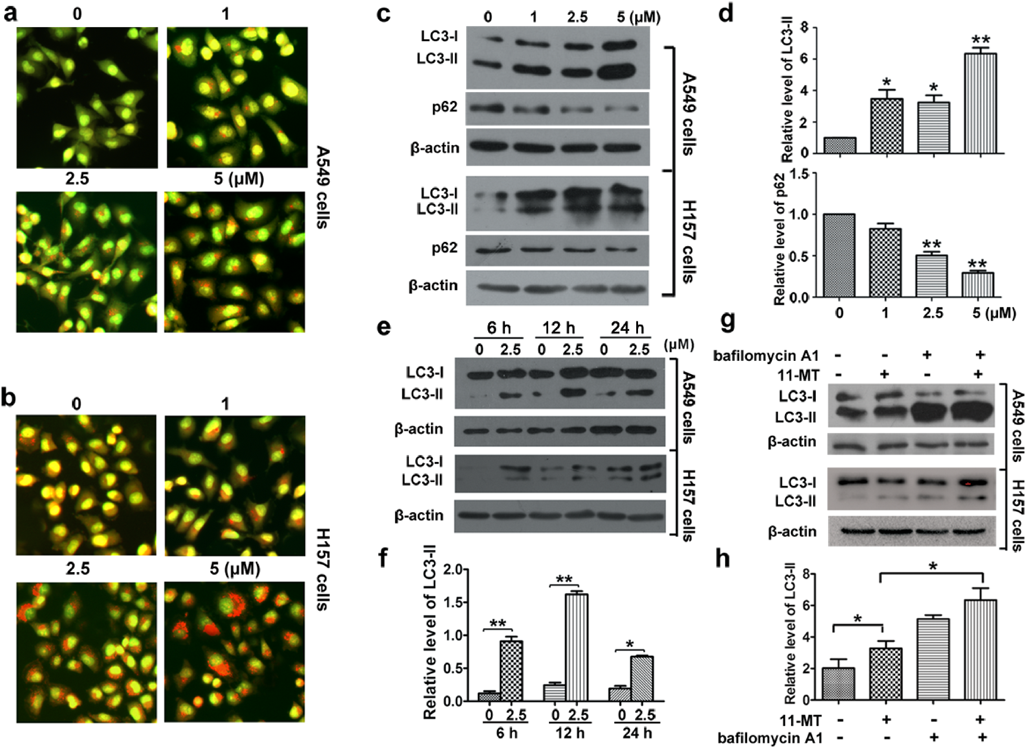

We next investigated the effect of 11-MT on autophagy in NSCLC cells. Acridine orange (AO) staining was first performed. In the control group, cells displayed green fluorescence in both cytoplasm and nucleus, while those treated with 11-MT displayed bright red fluorescent dots by AO staining (Figs. 3a, b), suggesting that 11-MT induced accumulation of acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs) in the cytoplasm. The combination of the soluble LC3-I with phosphatidyl ethanolamine to form a non-soluble LC3-II is a hallmark of autophagy.18) Thus, we examined the expression of LC3-II formation. After treatment with 11-MT at indicated concentrations for 24 h or at fixed concentration (2.5 µM) for indicated period of time, LC3-II levels increased in both cell lines (Figs. 3c–f). We further investigated the effect of 11-MT on autophagy flux. As p62 was reported to be involved in the formation of autophagosomes through specific binding with LC3 and was degraded by the autophagy pathway,19) it was then examined in the current work. The results revealed that 11-MT promoted the degradation of p62 in a dose-dependent manner (Figs. 3c, d). Bafilomycin A1 could block the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes by inhibiting the lysosome H+-ATPase, hence blocking the autophagy flux. We then co-treated the two cell lines with 11-MT and bafilomycin A1. The results of Western blot showed that there was a significantly aggravated accumulation of LC3-II (Figs. 3g, h). These observations suggested that 11-MT promoted an autophagy flux in A549 and H157 cells.

(a, b) A549 and H157 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 11-MT for 12 h and stained with acridine orange (AO). The bright red fluorescent dots indicated the acidic vesicular organelles (AVOs). (c) A549 and H157 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of 11-MT for 24 h. Levels of LC3-II, p62 and β-actin protein expression were analyzed by Western blot using their specific antibodies. (d) Densitometry results of ratio of LC3-II to β-actin. Ctr data were set to 1. Densitometry results of ratio of p62 to β-actin. Ctr data were set to 1. e A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for the indicated times. Levels of LC3-II and β-actin protein expression were analyzed by Western blot using their specific antibodies. (f) Densitometry results of ratio of LC3-II to β-actin in A549 cells. (g) A549 and H157 cells were pretreated with 20 nM bafilomycin A 1 for 1 h, and then coincubation with 11-MT (2.5 µM) for another 12 h. Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against LC3 and β-actin. (h) Densitometry results of ratio of LC3-II to β-actin in A549 cells. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3. (Color figure can be accessed in the online version.)

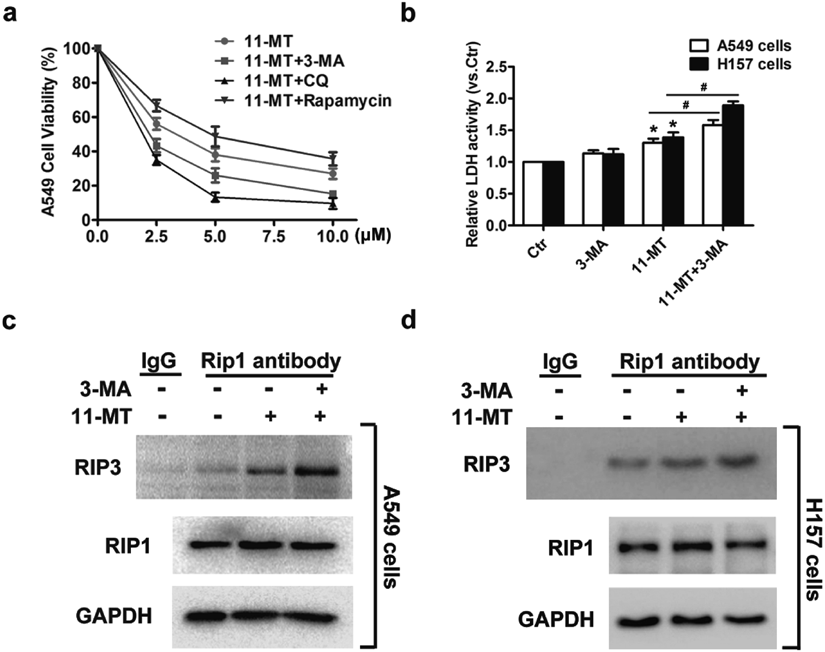

As autophagy is a mediator regulating cell fates and has dual effects in determining cell survival and cell death,20,21) we further studied the role of autophagy in 11-MT-induced cell death. To determine whether 11-MT-induced autophagy promotes or attenuates cytotoxicity, we used 3-methyladenine (3-MA, which block the upstream steps of autophagy) and chloroquine (CQ, which block the downstream steps of autophagy) to inhibit autophagy or rapamycin to promote autophagy in A549 cells, and then treated the cells with indicated concentrations of 11-MT for another 48 h. The combination of 3-MA or CQ with 11-MT further decreased the cell viability compared with mere 11-MT treatment while co-treatment of rapamycin with 11-MT increased the cell viability (Fig. 4a). Subsequently, we examined the effect of autophagy on necroptosis. The results showed that the LDH release and the interaction of RIP1 with RIP3 were both promoted after co-treatment with 3-MA and 11-MT, compared with 11-MT treated group (Figs. 4b–d). Based on these observations, we concluded that autophagy played a protective role in 11-MT-treated NSCLC cells.

(a) A549 cells were pretreated with 10 mM 3-MA or 3 µM CQ or 100 nm rapamycin for 1 h, and then coincubation with indicated concentrations of 11-MT for 48 h. Cells viability were analyzed by SRB assay. (b) A549 and H157 cells were pretreated with 10 mM 3-MA for 1 h, and then coincubation with 2.5 µM 11-MT. Cell necrosis were analyzed by LDH release after another 48 h treatment. (c,d) A549 and H157 cells were pretreated with 10 mM 3-MA for 1 h, and then coincubation with 2.5 µM 11-MT. The proteins were analyzed by Western blot after immunoprecipitation with an anti-RIP1 antibody after another 24 h treatment. RIP1 were detected by immunoblotting. * p < 0.05 vs. control, #p < 0.05, n = 3.

Since mTOR plays a central role in autophagy induction,22) we thus investigated whether 11-MT induced autophagy via mTOR inhibition in the two NSCLC cell lines. We detected the phosphorylation levels of mTOR (Ser 2448 site), eukaryote initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4EBP1) and 70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p70S6K), the latter two being substrates of mTOR. The two cell lines were treated with 11-MT at the indicated time, and the levels of p-mTOR, p-4EBP1 and p-p70S6K were then measured by Western blot. It was observed that the levels of p-mTOR, p-4EBP1 and p-p70S6K proteins decreased significantly after 11-MT treatment (Figs. 5a–c), suggesting that the autophagy was induced by 11-MT via inhibition of mTOR.

A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for indicated times. (a) Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against p-mTOR, mTOR and β-actin. The bar graphs show the ratio of p-mTOR to mTOR, with data for the non-treated group set to 1. (b) Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against p-4EBP1, 4EBP1, p-p70S6K, p70S6K and β-actin. (c) Densitometry results of ratio of p-4EBP1 to 4EBP1 and p-p70S6K to p70S6K in A549 cells. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3.

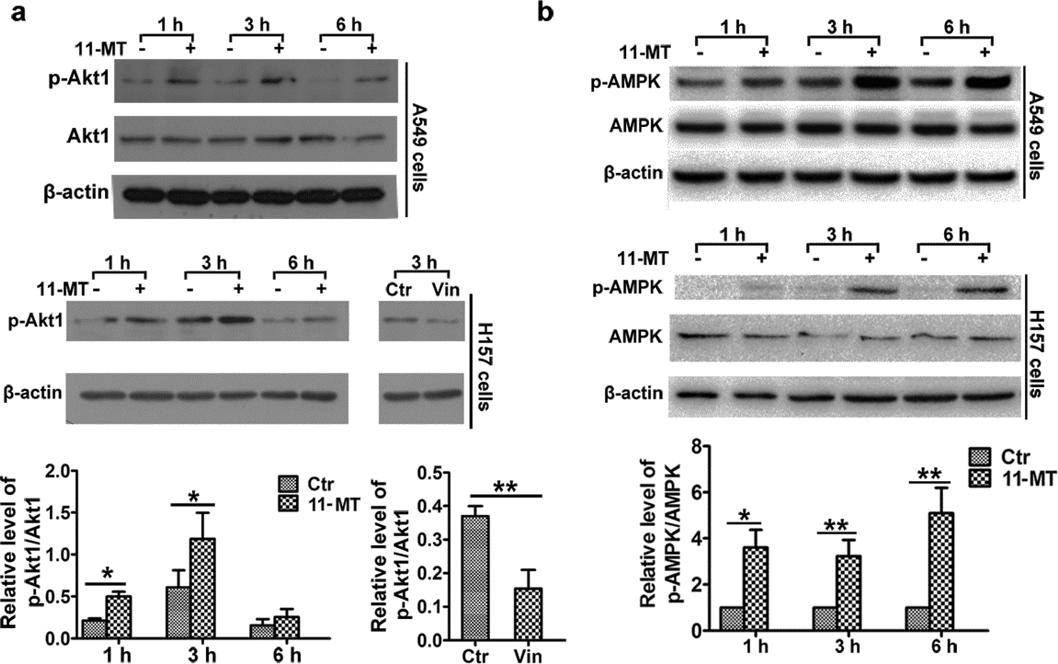

It is widely known that Akt1 is one of the main regulators of mTOR.23) We then detected the effect of 11-MT on Akt1 in the two NSCLC cell lines. Unexpectedly, the upregulation of p-Akt1 occurred at all indicated time in both cells (Fig. 6a), with vinorelbine as a positive control. Thus, Akt1 was not involved in suppression of mTOR activity in 11-MT induced autophagy. Another major candidate in mTOR activity regulation is AMPK, a key energy-sensing protein kinase in cells. By phosphorylating the Thr172 site of its catalytic α subunit, AMPK could be activated, and it then phosphorylates tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) and regulatory associated protein of mammalian target of rapamycin (RAPTOR), resulting in inhibition of mTORC1 activity.24) Thus, we measured the activity of AMPK. The results demonstrated that 11-MT could upregulate the phosphorylation of AMPK (Thr172) time-dependently (Fig. 6b). Therefore, our data suggested that the autophagy was initiated by 11-MT via AMPK-mTOR inhibition rather than Akt1-mTOR inhibition in both NSCLC cells.

A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for indicated times. (a) Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against p-Akt1, Akt1 and β-actin. Vinorelbine was used as positive control in H157 cells. The bar graphs show the relative levels of p-Akt1 to Akt1 in A549 cells (11-MT treated) and H157 cells (Vinorelbine treated), respectively. (b) Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against p-AMPK, AMPK and β-actin. Densitometry results of ratio of p-AMPK to AMPK, with data for the non-treated group set to 1. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3.

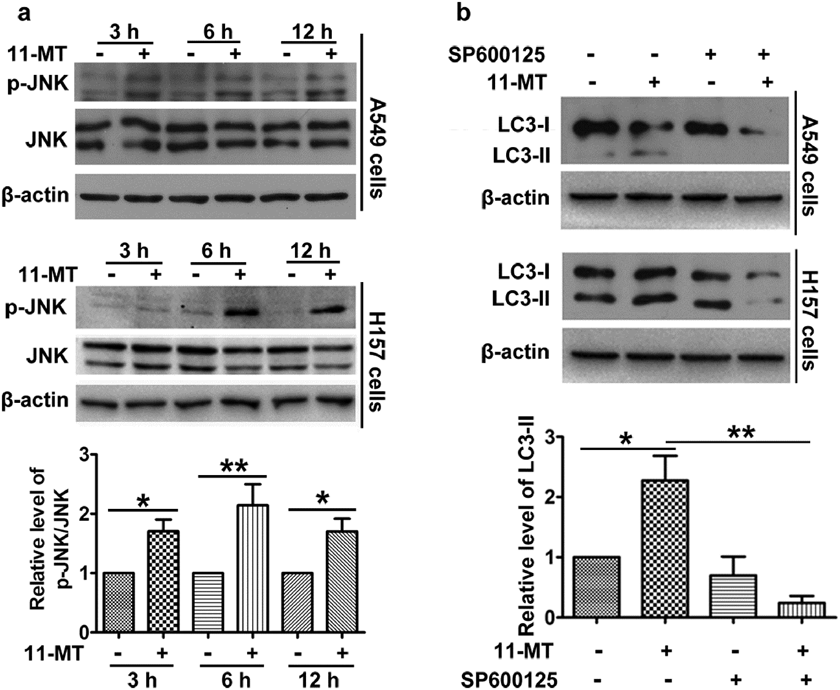

JNK, known as a stress-activated protein kinase, could be activated by a number of environmental challenges including toxins, UV irradiation and cytokines.25) Therefore, we first investigated whether JNK was activated by 11-MT. As expected, 11-MT significantly upregulated phosphorylation of JNK at 3, 6 and 12 h (Fig. 7a), which indicated that JNK was involved in the signal transduction induced by 11-MT. We next used SP600125 to inhibit JNK activity, and examined the role of JNK activity in autophagy. There was a pronounced decrease of the LC3-II level in SP600125 and 11-MT co-treated group compared with sole 11-MT treated group (Fig. 7b). Hence, 11-MT induced autophagy via phosphorylation of JNK.

(a) A549 and H157 cells were treated with 2.5 µM 11-MT for indicated times. Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against p-JNK, JNK and β-actin. The bar graphs show the relative levels of p-JNK to JNK in A549 cells, with data for the non-treated group set to 1. (b) A549 and H157 cells were pretreated with 10 µM SP600125 for 1 h, and then coincubation with 2.5 µM 11-MT for another 12 h. Levels of protein expression were detected by Western blot using antibodies against LC3-II and β-actin. The bar graphs show the relative levels of LC3-II to β-actin in A549 cells. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, n = 3.

The current work has provided evidences that necroptosis pathway can be activated by 11-MT in human lung cancer A549 and H157 cell lines. In summary, 11-MT induced non-apoptotic cell death that was suppressed by blockage of the key necroptosis pathway member RIP1; 11-MT strongly induced autophagy through AMPK–mTOR and JNK signaling pathways; and suppression of autophagy effectively promoted 11-MT-induced necrosome formation and necroptotic cell death.

Literature reports showed that two aspidosperma alkaloids caused significant apoptosis in several human cancer cells. Jerantinine A induced pro-apoptotic effect in human colorectal, breast and lung carcinomas,8) while jerantinine B induced dose-dependent activation of caspase-3 and -7 and also cleaved-poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase (PARP) accumulation in A549, MCF-7 and HCT-116 cells.7) Unexpectedly, our present work revealed that 11-MT did not promote any apoptotic cell death in NSCLC cells. Currently, induction of apoptosis is involved in the anticancer activity of many chemotherapeutics, which is the main mechanism to directly kill cancer cells.26,27) However, numerous cancer cells are defective in apoptosis induction or have acquired apoptosis resistance, leading to chemoresistance.26) Recently, some natural products have been found to induce an alternative non-apoptotic death in cancer cells. For example, shikonin is the first natural compound reported to induce necroptosis in osteosarcoma,28) glioma29) and multiple myeloma cells30); Curcumin induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) or p38/JNK phosphorylation followed by production of abundant reactive oxygen species (ROS) that promote necroptosis in prostate cancer cells.31) In this study, 11-MT induced necroptotic cell death in lung cancer cells. Such role of natural compounds in regulating necroptosis will hopefully provide prospective strategies to manipulate tumor cell death.

Autophagy is an essential process that degrades and recycles harmful and damaged cellular materials to mediate metabolic adaptation, as well as maintain energy homeostasis under the stress response.32) In this study, we demonstrated that 11-MT could induce autophagy in human lung cancer cells. The role of autophagy in regulating cell death is complex, making the caution in modulation of autophagy for cancer therapy. In some cases, autophagy-associated cell death is accompanied with necrosis or apoptosis.33) In other cases, autophagy is often induced to protect cancer cells against chemotherapy. Indeed, neoalbaconol-induced autophagy provides a survival role in nasopharyngeal carcinoma C666-1 cells, while apoptosis and necroptosis are responsible for neoalbaconol-induced cell death.34) In NSCLC cells, shikonin-induced necroptosis is promoted by the inhibition of autophagy.35) In this study, 11-MT independently induced necroptosis in lung cancer cells, and autophagy promoted by 11-MT mediated a protective effect against necroptosis. Therefore, combination therapy of autophagy inhibitors and these potential anticancer drugs could be an effective therapeutic strategy for killing cancer cells.

In response to a broad range of stresses, AMPK, a sensor of cellular energy status, is activated, and then it could induce multiple mechanisms including autophagy to mediate the metabolic flexibility to help cell survive.36) In addition, AMPK phosphorylates TSC2, which plays a key role in regulation of the mTOR pathway of autophagy; AMPK phosphorylates raptor that contributes to the inhibition of mTOR,24,36) suggesting that the mTOR activity is regulated by AMPK. Our current investigation revealed that 11-MT downregulated the activity of mTOR while promoted AMPK activity, indicating that 11-MT promoted autophagy dependent of AMPK–mTOR signaling pathway. Recent studies indicate that AMPK plays a dual roles and have pro- or anti-tumorigenic effects in cancer progress depending on context.37) We here demonstrated that autophagy stimulated by AMPK–mTOR signaling was involved in promoting cell survival, which suggested that AMPK activation exerted a positive effect on lung cancer cell survival as response to 11-MT treatment.

JNKs, initially identified as the stress-activated protein kinases, participate in autophagy in response to multiple stimulations, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, endoplasmic reticulum stress and insulin-like growth factor-1. Under the deprivation of amino acids or stresses stimulation, the complicated signaling network converges on JNK.25) The activated JNK regulates autophagy via multiple mechanisms. Firstly, when activated, JNK phosphorylates Bcl-2, which dissociates Bcl-2 with Beclin1 and contributes to the Beclin1-related phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) complexes and then regulates autophagy.38) Secondly, the activated JNK leads to c-Jun/c-Fos activation, enhancing its transcription activity on Beclin 1.25) Thirdly, activated JNK promotes FoxOs nuclear localization, and promotes autophagy via FoxO-dependent transcription of ATG genes.25) In our study, 11-MT could upregulate JNK phosphorylation in a time-dependent manner in human NSCLC cells. Furthermore, upon treatment of JNK inhibitor in combination with 11-MT, the level of LC3-II was downregulated. We thus confirmed that JNK was the crucial mediator of 11-MT-induced autophagy. That which downstream signaling of JNK is involved in 11-MT-induced autophagy remains a work in due course.

Taken together, our studies established a different mechanism of 11-MT for killing cancer cells from that of previously reported aspidosperma alkaloids. During this process, 11-MT also promoted autophagy, which played a protective role against necroptosis. Therefore, 11-MT in combination with autophagy inhibitors could be more effective to kill lung cancer cells. In addition, this natural indole alkaloid could be potentiated to kill cancer cells that are resistant to other apoptosis-inducing chemotherapeutics. Further study is warranted to examine the efficacy and possible side effects of this molecule for anticancer chemotherapy.

Antibodies against RIP3 (13526), LC3B (2775), p-mTOR (2971), mTOR (2972), p-4EBP1 (9456), 4EBP1 (9452), p-p70S6K (9206), p70S6K (9202), p-Akt1 (9018), Akt1 (9272), p-AMPK (2531), AMPK (2532), p-JNK (9251), JNK (9252), PARP1 (9542), and caspase 3 (9662) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, U.S.A.). Anti-RIP1 (610458) and anti-p62 (610833) were bought from BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). Anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (sc-47724) and β-actin (sc-47778) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, U.S.A.). The secondary antibodies HRP-conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (sc-2371) and anti-rabbit IgG (sc-2004) were also purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The JNK inhibitor SP600125 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Bafilomycin A1, 3-MA and z-VAD-FMK were bought from Selleck (Shanghai, China). Necrotatin-1 was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Cell Lines and Cell CultureCell lines A549 and H157 used in this study were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. The cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, R6504) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, SV30087.02) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2.

Acridine Orange Assay for Acidic Vesicular OrganellesThe volume of the AVOs was determined by staining with the lysosomotropic agent AO (Sigma-Aldrich, 235474). After treatment with 11-MT, the cells were incubated with AO (5 µg/mL) at 37°C for 1 min. After washed with PBS, the cells were observed with fluorescence microscopy (Leica, Germany). The nucleus and cytoplasm of the stained cells glow bright green fluorescence, while the AVOs fluoresced bright red.

Cell Viability AssayCell viability assay was conducted as previously described.39) In brief, cells were seeded in 96-well cell culture plates and cultured overnight. Then the cells were treated with the tested alkaloids at indicated concentrations. After another 48 h, the cells were fixed by glacial acetic acid and subjected to measuring the cell number with the sulforhodamine B (Sigma-Aldrich, 341738) assay.

LDH Release AssayWhen cells cultured in 24-well cell culture plate reached subconfluence, they were treated with indicated concentrations of 11-MT or 3-MA. After treatment for certain time, the LDH release was measured using LDH cytotoxicity detection kit (TaKaRa, MK401).

Cell Apoptosis AssayApoptosis was examined using the ANXA5-PE/7-AAD apoptosis detection kit from BD Biosciences (11774425001) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Caspase activation and PARP1 cleavage were detected by Western blot.

Western Blot AnalysisAfter treatment, the cells were lysed by lysis buffer with 25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 6.8), 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 6% glycerol, 2 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, P8340) at 4°C. Then the whole-cell protein lysates was added with 0.02% bromophenol blue and boiled for an additional 5 min. The total protein extracts (20 µg) were separated using 12% or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The separated protein in gel was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, ISEQ09120). Then, the membrane was blocked using 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk (Cell signaling, 9999S) in PBS Tween 20 (PBST; 0.05%) for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibodies (1 : 1000–1 : 10000 in PBST) at 4°C overnight. After three times washing in PBST, the membrane was then incubated with the HRP conjugated secondary antibodies (1 : 10000) at room temperature for 1 h. The Pierce ECL (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 32106) Western blotting system was used to develop the immunoreactive bands. The protein relative quantity was analyzed using the Image J software (National Institutes of Health, U.S.A.).

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)After treatment, A549 or H157 cells were washed and then lysed with IP buffer (Beyotime, P0013). The whole protein lysates were collected by centrifugation and incubated with 5 mg of antibodies or normal IgG as negative control. Then the protein A/G agarose beads (Beyotime, P2012) were added overnight at 4°C.

After three times washing with IP buffer, the immunocomplexes were separated using 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subjected to Western blot analysis.

Statistical AnalysesAll experiments were performed at least three times independently. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) The differences between groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p < 0.05. Adobe Photoshop CS4 (Adobe, San Jose, U.S.A.) was used to process all images. The relative quantity of the protein bands was analyzed using the Image J software (National Institutes of Health, U.S.A.).

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31501122, 21772065, 81500375, 81603215), Shandong Excellent Young Scientist Award Fund (BS2014SW031), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (JQ201721, ZR2017MH019, ZR2015HQ001), Shandong Provincial Key R&D Project (2018GSF118158), the Science and Technology Developmental Project of Shandong Province (ZR2014CM030), Innovation Team Project of Jinan Science & Technology Bureau (No. 2018GXRC003), and Shandong Talents Team Cultivation Plan of University Preponderant Discipline (No. 10027).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The online version of this article contains supplementary materials.