2020 Volume 68 Issue 3 Pages 251-257

2020 Volume 68 Issue 3 Pages 251-257

A concise spherical granulation method is required to prepare extemporaneously granules remanufactured from oral dosage forms for administration to individuals who cannot swallow tablets or capsules. In this study, we determined the feasibility of spherical granulation using a planetary centrifugal mixer. A model formulation, 20% ibuprofen (IBP) granules, was prepared using a lactose/cornstarch (7 : 3, w/w) mixture or D-mannitol as diluents, and changes in granule characteristics (mean diameter (d50), distribution range of granule size (span), and yield) were evaluated according to the amount of water added and the granulation time. The amount of water was assessed using the plastic limit value as measured using a digital force gauge. We successfully produced granules, and larger amounts of water and longer granulation times resulted in larger d50 values and smaller span values. The optimal granulation time was 45 s and the optimal water contents were 70 and 67.5% of the plastic limit value for the lactose/cornstarch mixture and D-mannitol, respectively. When compared to commercial 20% IBP granules, powder X-ray diffraction and differential scanning calorimetry analyses showed that the granulation process did not alter the crystallinity of the drug. Thus, this novel granulation method using a planetary centrifugal mixer may be a promising technique for compounding in pharmacies and in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Granule formulations are superior to powder formulations because they are easier to dispense precisely, and provide for easy dosing of pediatric patients. Pharmacists have proposed use of granule formulations (e.g., 20% aminophylline granule or 0.01% digoxin granule) as hospital preparations to replace powder forms.1,2) These preparations are typically manufactured on a scale of several hundred grams using a manual extrusion method. However, production in pharmacies requires smaller scale preparations due to limited numbers of patients who require these formulations. A large amount of material is required to operate conventional granulators, and preparation of small amounts of granules with high yield is a significant challenge.3) In contrast, manual extrusion methods are labor-intensive and time-consuming. Therefore, a machine is needed that is capable of preparing small batches (tens of grams) with high yield (more than 90%) and high quality (high sphericity). In this study, we used a planetary centrifugal mixer (known as an ointment mixer4) or PCM) to prepare granules in the pharmacy.

A PCM is a type of rotating-vessel mixer with no agitator that produces strong convective flow by means of revolution and rotation.4) Although the PCM has many advantages over other mixing machines for blending materials, it has only been used for kneading ointments in clinical settings.5,6) Recently, we reported the feasibility of using a PCM for producing uniform powder blends7–9) free from cross-contamination due to use of disposable vessels.10) However, use of a PCM for small-scale spherical granulation has not been previously reported.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the feasibility of performing spherical granulation using a PCM. Granule formulations containing ibuprofen (IBP), a common active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), were prepared using two different formulations with 20% IBP content. The effects of water content and granulation time on the characteristics of the resultant granules were thoroughly investigated, as water content is a crucial parameter in wet granulation.11,12)

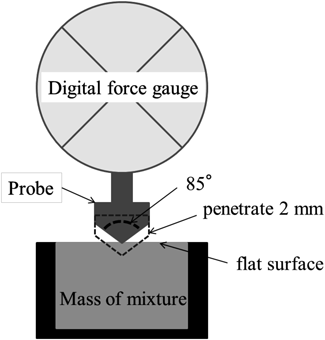

The plastic limit (PL) value, which represents the packing structure of particles and water in powders, was determined to standardize the water content of different materials. Newitt and Conway-Jones proposed the existence of three packing structures with increasing moisture content13): the pendular state, the funicular state, and the capillary state. Surface tension at the particle–liquid interface and the presence of liquid bridges causes formation of first agglomerates in the pendular state. Increasing liquid content results in formation of a continuous network of liquid in the funicular state. Pore spaces are completely filled to produce the capillary state. The water content in the capillary state is referred to as the PL value. To determine the PL value mechanically, we used a digital force gauge to measure penetration resistance force according to a method developed for this study. The penetration resistance force, which was detected when a conical probe penetrated into the mass, reflected the packing structure of the mass.14)

The selected preparations of 20% IBP granules were examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), and dissolution to compare the properties of the granules to those of the commercially available 20% IBP granules, Brufen® Gr. 20%.

Lactose monohydrate and cornstarch were purchased from Pfizer Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and used for a mixture of 7 : 3 (w/w) as a diluent because it is generally used for standard formulations. D-Mannitol (Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) was also used as a diluent. Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Corporation and used as a binder. Ibuprofen 50® (IBP) was supplied by BASF Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) as an API. Brufen® Gr. 20% was purchased from Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). Ultrapure water was used as a wetting agent. Methanol and acetonitrile of HPLC grade were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Corporation. All other reagents were of reagent grade.

Measurement of Penetration Resistance ForceFour grams of powder was weighed into an ointment container (UG35-mL, Umano chemical, Osaka, Japan), a predetermined amount of water was added, and the mixture was kneaded at a speed of 1000 rpm for 60 s in a mixer (NR-500, Thinky Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The wet mass was added to a sample vessel (14 mmϕ ×5 mm) and the surface of the wet mass was flattened using an attachment plate. A conical probe (10 mmφ, taper angle; 85°) connected to a digital force gauge (DST-50N, Imada Co., Ltd., Toyohashi, Japan) penetrated into the mass to a depth of 2 mm as illustrated in Fig. 1. The penetration speed was approximately 1 mm/s. The penetration resistance force was plotted as a function of the water-to-solid ratio to determine the amount of water that resulted in the maximum penetration resistance force. The PL value of the powder or mixture was calculated as the sum of the measured water amount and the absorbed moisture in the powder. Absorbed moisture was measured according to the Japanese pharmacopeia 17th Ed.,15) which instructs that each raw material (5 g) should be heated until a constant weight is achieved.

Twenty percent IBP granules were prepared using two formulation compositions. The formulations were composed of 20% IBP, 5% CMC, and 75% lactose-cornstarch mixture (named PM-A) or 75% D-mannitol (named PM-B). A predetermined amount of each ingredient was weighed into a plastic container (UG58-mL, Umano chemical) and blended at 1200 rpm for 60 s in the PCM (Material Equalizer, Beat Sensing Co., Ltd., Shizuoka, Japan). For all experiments, the filling rate of the vessel was about 20% and the total powder mass was 10 g. A predetermined amount of water was added using a metered spray bottle (0.1 mL/squeeze) and the mixture was granulated at 1200 rpm for the specified times (15, 30, 45, 60, and 75 s) in the PCM. The granules were then dried in an oven at 50°C until they reached a constant weight.

Granule A (GR-A) was prepared from PM-A with a 70% PL value for water and 45 s granulation time. Granule B (GR-B) was prepared from PM-B with a 67.5% PL value for water and 45 s granulation time.

Evaluation of Granulation Efficiency and Granule CharacteristicsYield of GranulesSpherical granule yield was determined by weighing after drying. Dry granules were passed through a 4000-µm sieve followed by a 355-µm sieve to remove any oversized agglomerates and fines. As a result, only spherical granules were collected for this study. The remaining spherical granules were measured, and yield (%) was calculated based on Eq.1.

| (1) |

The particle size distributions of the granules were measured using a series of standard sieves including 355, 425, 500, 600, 710, 850, 1000, 1180, 1400, 1700, 2000, 2360, 2800, and 3350 µm for 20 s, after which 2 g of powder was sieved. The individual sieves were weighed to estimate the amount of the powder remaining. The particle size distribution and accumulated average particle size (d50) were evaluated using a log-normal distribution. The span was defined using Eq. 2.

| (2) |

where d10 and d90 represent the cumulative 10 and 90% of particle size diameters, respectively.

Determination of CircularityGranule shape was determined using a microscope (M3, Schalar Co., Ltd., Tokyo Japan) equipped with a 30× lens (30N, Schalar Co., Ltd., Tokyo Japan). Sphericity was evaluated using the circularity of the projected image of the granules. The images obtained were analyzed using ImageJ (ver. 1.51, National Institute of Health, U.S.A.) for circularity (Eq. 3).

| (3) |

A circularity value of 1.0 indicated a perfect circle. The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.) of thirty granules.

Characterization of 20% IBP GranulesSEMGranules were distributed on double-sided adhesive tape placed over an aluminum stub. The granules were coated with gold in a sputter coater (MSP-1S, Vacuum Device Co., Ltd., Mito, Japan) at 40 mA for 2 min. Imaging was performed using a field emission SEM (TM3030, Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

PXRDThe PXRD was conducted using a MiniFlexII (Rigaku Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a voltage of 30 kV and a current of 15 mA. The samples were scanned across the 2θ range of 5–35° at 4°/min using a Cu-Kα radiation source.

DSCDifferential scanning calorimetry was performed using a DSC instrument (DSC7020, Hitachi Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) under a nitrogen atmosphere. Samples were packed in aluminum pans, then heated at 10°C/min.

Assay of Fractional Content UniformityContent uniformity analysis was performed to evaluate the distribution of the API in the final granules in different sieve fractions. The granules were divided into six fractions: 355–500, 500–710, 710–850, 850–1000, 1000–1400, and 1400–1700 µm. The frequency (%) and drug content of each fraction was determined. Approximately 100 mg of sample was dissolved in 100 mL of dissolution test 2nd fluid and analyzed by HPLC as described in “Determination of IBP by HPLC” All experiments were performed in triplicate. The amounts of the 1700–2000, 2000–2800, and 2800–4000 µm fractions were too small to assay the API content.

DissolutionDissolution was performed according to the dissolution test (paddle method) of the Japanese pharmacopeia 17th Ed. (Ministry of Health Welfare and Labor, 2016) using a dissolution apparatus (NTR-6100 A, Toyama Sangyo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The dissolution medium (900 mL) was phosphate-citrate buffer (pH 5.5), and the temperature was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C. The paddle speed was set to 50 rpm. Granules (1 g) or IBU powder (200 mg) were added to the dissolution medium. Sample medium was collected at 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 360 min, then filtered through a 0.45-µm filter (Minisart RC15, Sartorius Japan K.K, Tokyo, Japan) prior to analysis. The amount of dissolved drug was analyzed using HPLC as described below. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Comparison of dissolution profiles was performed by calculating an f2 value.16) F2 values greater than 50 indicated similar profiles.

Determination of IBP by HPLCThe concentration of IBP was analyzed using an HPLC system (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) that consisted of a pump (LC-10AS), a sample injector (SIL-10A), and a UV-Vis spectrophotometric detector (SPD-10A). A C18 column (Shim-pack GWS, 5 µm, 4.6 mm ×150 mm, Shimadzu GLC Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used for separation, and IBP was detected at 264 nm. The mobile phase was 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 2.6) with acetonitrile (40 : 60, v/v).17)

Our initial results showed that the amount of water is a critical parameter that needs to be precisely controlled. To determine the optimal amount of water, the penetration resistance force of the diluents was plotted as a function of the liquid-to-solid ratio to determine PL value, as shown in Fig. 2. An early sudden increase in the penetration resistance force was noted in the pendular state. Subsequent constant force implied that the powder was in the funicular state. Then, the penetration resistance force increased with addition of more water, with a peak at the PL of the diluents, followed by reduction of the penetration resistance force. The maximum penetration force was identified. The water content of the powder was calculated by summing the amount of added water and the amount of absorbed moisture. The PL values measured in this study are summarized and compared to previously reported values in Table 1.18,19) The measured values in this study were 1.23- to 1.30-fold greater than previously reported values. This indicated that more precise values could be obtained using the present method due to less evaporation of water during measurement. In previous studies that determined PL values, a wet mass was produced using a mortar and pestle, and then rolled into a rod by hand.20) In the present method, a wet mass was produced in a closed vessel using a mixer, and force measurements were acquired within in a few seconds using a digital gauge.

●, lactose; ▲, cornstarch; ■, D-mannitol, □; ibuprofen–cornstarch mixture (1 : 2) Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

| Diluent | Measured value* (mL/g) | Reported value (mL/g) | Ratio of measured/reported value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactose | 0.23 ± 0.01 | 0.18 a) | 1.30 |

| Corn starch | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.67 a) | 1.23 |

| D-Mannitol | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.20 b) | 1.27 |

*: Values are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3). a) ; ref. 18), b) ; ref. 19).

To investigate the feasibility of spherical granulation using a PCM, 20% IBP granules were prepared and evaluated compared to commercial Brufen® Gr. 20%. We used CMC as a binder, and a lactose-cornstarch mixture or D-mannitol as a diluent. The PL values of the ingredients were examined using the method described in “Measurement of Penetration Resistance Force.” Figure 2 shows the penetration resistance force profile of the 1 : 2 mixtures of IBP and cornstarch, which shows that the PL value was 0.61 mL/g. In general, the PL value of a mixture is calculated by summing the PL value of each material multiplied by the content percentage of the material. Therefore, the PL value of IBP was 0.16 mL/g.

Figure 3 shows the penetration resistance force curves of the physical mixtures consisting of API, binder, and diluents. In both formulations, the maximum force point was determined, and the PL value of each formulation was obtained from the result. The measured PL values for PM-A and PM-B were 0.37 and 0.25 mL/g, respectively, and the calculated values of PM-A and PM-B without CMC were 0.36 and 0.24 mL/g, respectively. Thus, the measured PL values were 0.01 mL/g greater than the calculated values for both formulations, indicating that the differences were due to CMC. However, the intrinsic PL value for CMC was unknown because it could not be measured using a general method due to the high viscosity of wetted CMC.

●, PM-A; ■, PM-B; Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

We performed thorough granulation studies using various granulation times and water content to explore water content range for which it was possible to granulate PM-A and PM-B. When the yield of granules (as shown in “Yield of Granules”) was larger than 95%, we considered as “possible.” The results are summarized in Fig. 4. The water amount was normalized by the intrinsic PL values of the lactose-cornstarch mixture (Fig. 4a) or D-mannitol (Fig. 4b). The granulation time ranges examined for PM-A and PM-B were 30–90 and 15–75 s, respectively, because of differences in agglomeration rate for each diluent. The results showed that spherical granulation was possible across relatively wide time ranges when using an appropriate water content.

(a) PM-A, (b) PM-B.

All granules produced in this study were characterized by mean diameter, span, and circularity. The effects of water content and granulation time on the mean diameters are displayed in Fig. 5. In all cases, the mean diameters increased with increased water content. Interestingly, the smallest size was nearly the same regardless of granulation time. As such, granules of the same size could be prepared using different water contents and granulation times.

(a) GR-A, (b) GR-B; ●, 15 s; ▲, 30 s; ■, 45 s; ◆, 60 s; +, 75 s; ×, 90 s.

Figure 6 shows the effects of water content and granulation time on span. Span decreased with increased water content, and lower values differed as a function of water content. Agglomeration progressed with increased granulation time, resulting in larger granules, and decreased numbers of granules, and a narrower span. As a result, the span was decreased.

(a) GR-A, (b) GR-B; ●, 15 s; ▲, 30 s; ■, 45 s; ◆, 60 s; +, 75 s; ×, 90 s.

Circularity ranged from 0.60 to 0.75 in all granules (data not shown). Differences in circularity were relatively small across the ranges of water content and granulation time, which indicated that circularity was not substantially influenced by water content or granulation time. Circularity generally depends on the method of granulation.21) Our results were similar to those obtained with granules produced by rotary granulation, which indicated that the mechanism of granulation in our study was rotation of granules in the vessel.

Effect of Diluent on Product PropertiesTo provide a comparison to Brufen® Gr. 20%, we selected granulation conditions for typical 20% IBP granule products: GR-A and GR-B. The granulation time was 45 s and the water contents for GR-A and GR-B were 70 and 67.5% of the PL values, respectively. Table 2 shows the characteristics of GR-A and GR-B, which had similar mean diameters and circularity values. Brufen® was superior to these formulations in span and circularity.

| Formulation | GR-A | GR-B | Brufen® |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean diameter (µm) | 817 | 880 | 1006 |

| Span | 0.88 | 1.08 | 0.36 |

| Circularity a) | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.79 |

| Yield (%) | 94.0 | 96.5 | — |

a) ; Data are presented as the mean (n = 30).

Table 3 summarizes the drug content uniformity among the size fractions. The contents of each size fraction ranged from 82.1 to 98.3% in GR-A and 80.7 to 107% in GR-B. The drug loading percentage decreased with decreasing granule size. In general, rotary granulation results in low content uniformity.22,23) In this study, the mass percentages of the fractions with the lowest drug content were 6.2 and 8.2% for GR-A and GR-B, respectively. Therefore, the compositions of the formulation needed to be improved to achieve allowable content uniformity for clinical use beyond this feasibility study.

| Size fraction (µm) | GR-A | GR-B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass percent | Drug loading percent | Mass percent | Drug loading percent | |

| 1400–1700 | 13.3 | 98.3 ± 8.3 | 17.8 | 100.8 ± 5.4 |

| 1000–1400 | 24.4 | 95.6 ± 4.7 | 26.2 | 107.0 ± 6.8 |

| 710–1000 | 30.9 | 89.8 ± 4.6 | 24.6 | 101.9 ± 4.0 |

| 500–710 | 20.0 | 85.6 ± 4.3 | 12.7 | 101.6 ± 9.5 |

| 355–500 | 6.2 | 82.1 ± 5.0 | 8.2 | 80.7 ± 1.6 |

Drug loading percent represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

To investigate the properties of the formulations produced in our study, we visualized granule surfaces using SEM. Images are displayed in Fig. 7. Agglomerated particles were observed, and the surfaces of the granules were not smooth. Crystals were observed, which indicated that the diluents did not dissolve or melt during the granulation procedure.

In this study, we used IBP as a model drug. The melting point of IBP is 75–77°C.24) Since melting or dissolution of IBP during granulation could alter its crystallinity, we evaluated the crystallinity of the granules. Figure 8 shows the PXRD patterns of IBP, physical mixtures, and granules. Typical peaks at 6 and 22°25) were observed in all samples, which indicated that IBP remained crystalline after preparation.

(a) IBP, (b) PM-A, (c) GR-A, (d) PM-B, (e) GR-B, (f) Brufen®.

DSC measurements were performed to assess the impact of the granulation procedure on the thermal properties of IBP. Figure 9 shows DSC thermograms of IBP, physical mixtures, and granules. All samples showed similar patterns and peak positions, and an endothermic peak was observed at 77°C, which was due to melting of IBP. This result further suggested that IBP remained in the crystalline state following granulation.

(a) IBP, (b) PM-A, (c) GR-A, (d) PM-B, (e) GR-B, (f) Brufen®.

Figure 10 shows the dissolution profiles of IBP from the granulated formulations. Brufen® showed a rapid dissolution profile indicative of immediate release. In contrast, dissolution of GR-A and GR-B was slightly slower than that of the IBP powder. The similarity factors of GR-A and GR-B to the IBP powder were 58.2 and 47.9, respectively. This indicated that the IBP particles in GR-A were released independently with disintegration of the granule and dissolved into the medium because GR-A contained cornstarch, a disintegrant. In contrast, GR-B disintegrated slowly because no disintegrant was present in the formulation. Therefore, the dissolution of IBP from GR-B was retarded slightly compared to that from GR-A.

●; ibuprofen powder, ▲; GR-A, ■; GR-B, □; Brufen® Each value represents the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

The aim of this study was to demonstrate the feasibility of spherical granulation using a PCM, with the goal of developing a novel granulation technology using dispensing machines present in pharmacies. We successfully prepared a model formulation, 20% IBP granules, and developed a concise method to determine the PL value for selecting the optimal water content. This study was the first to show that spherical granulation using a PCM could be performed in rapidly with high-yield and high-sphericity.

Wet granulation has been used for hospital preparations in pharmacies, where extrusion/spheronization is the most frequently used method. However, this method requires relatively large amounts of materials and long processing times, making it inadequate for extemporaneous preparation in pharmacies. Due to these limitations, we aimed to develop a novel technology. The planetary centrifugal granulation method presented in this study has potential to fulfill the needs of pharmacists to manufacture extemporaneous preparations.

The most critical process parameter of wet granulation is the amount of water used as a binder solution. However, with our wet granulation method, granule growth could not be monitored using a typical on-line torque meter because granulation was performed in a closed system and granulation time was extremely short. Therefore, we also developed a predictive method to estimate the amount of water needed for granulation based on the PL value. Instead of using the typical manual method, we measured penetration resistance force using a digital force gauge (Fig. 1) to determine the PL value of each formulation (Fig. 3). Thus, a process parameter map (water content-granulation time) was constructed from the results of this evaluation to predict granule particle size distribution (Figs. 4, 5). These results indicated that this method could be suitable for use with other formulations.

This study was limited in scope, as we only prepared 20% IBP granules as a model medicine. However, our intent is to use this method for reconstruction of granules from crushed tablets or open capsule contents. Our study demonstrated the feasibility of remanufacturing tablets or capsules to granules for dispensing and dosing. With appropriate quality testing, these granules could be used to treat patients who cannot swallow tablets or capsules.

Granulation is applicable to a wide variety of industries including the food, agricultural, and pharmaceutical industries. The granulation method presented in this study may also benefit other scientific fields.

Spherical granulation using a PCM is efficient for preparing small batches in a short amount of time. Granulation could be performed in small batches (for example, 10 g in a 58-mL vessel) within 15–45 s. Use of a PCM enabled preparation of 20% IBP with high yield and appropriate quality. The method in this study utilized one-pot processing and a closed system, ideal for formulating expensive or potent drugs. This study also proposed methods for measuring PL values and predicting appropriate conditions to prepare the desired granules. This effective granulation method could benefit pharmacists by allowing for extemporaneous compounding of dosages for pediatric patients.

The authors thank BASF Co., Ltd. for kindly supplying Ibuprofen 50®. We also thank Beat Sensing Co., Ltd. for leasing the PCM (material equalizer).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.