2025 Volume 73 Issue 9 Pages 783-786

2025 Volume 73 Issue 9 Pages 783-786

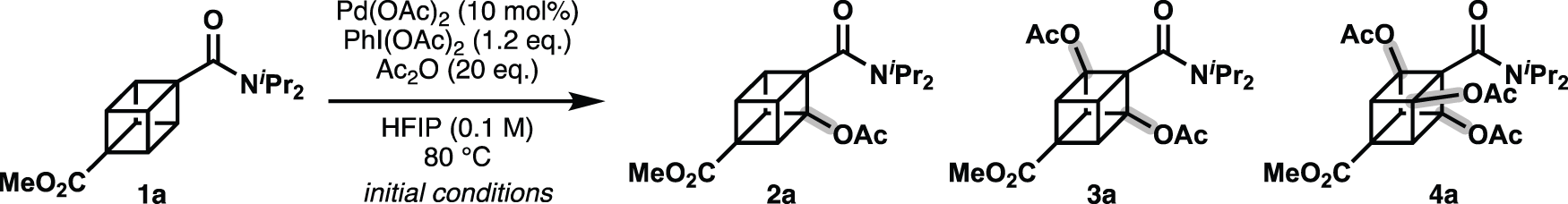

In this study, a palladium-catalyzed, amide-directed C–H acetoxylation of cubanes has been developed. The ortho positions of the amide directing group on cubanes were selectively acetoxylated without any stoichiometric strong bases. The number (1–3) of acetoxy groups introduced was determined by the amount of PhI(OAc)2 used. Substitution at the C4 position of cubane dramatically affected the outcome of the acetoxylation reaction.

Cubane is a hydrocarbon with a unique cubic carbon skeleton1,2) (Chart 1a). This fascinating structure has attracted widespread attention from chemists, and extensive research has been conducted in a wide range of fields, including physical organic chemistry and materials chemistry.3) Recently, the medicinal use of cubane as a bioisostere of the benzene ring has increased because of its structural similarity to substituted benzenes (Chart 1b). Since its feasibility was first demonstrated,4) related studies have been extensively performed, and its utility has been broadly elucidated.5–7) Further expansion of cubane’s applications in various scientific fields requires precise methods for its decoration, but such methodologies remain limited.

The C–H functionalization methodology is useful for obtaining multifunctionalized cubanes. Historically, amide-directed C–H metalation was the first disclosed method for cubane C–H functionalization8) (Chart 2a). Cubane tertiary amides have predominantly been employed for this purpose, and several functionalizations based on this methodology have been reported.9–14) Our group expanded the directed metalation methodology into directed C–H activation, developing a C–H acetoxylation of cubanes using an oxime-directing group.15) This directing group is removable by reductive cleavage of its N–O bond, allowing acetoxylated cubanes to be derivatized into analogs of pharmaceutically relevant scaffolds containing benzene rings (Chart 2b). Given the precedent of amide-directed metalation with strong bases, we questioned whether the amide group could also serve as a directing group for the C–H activation of cubanes (Chart 2c). Although harsh conditions are required for further transformations, amide groups can be easily introduced into the cubane core from commercially available cubane dicarboxylates. Herein, we describe the Pd(II)-catalyzed, amide-directed C–H acetoxylation of cubanes (Chart 2d).

Following reported tertiary amide-directed C–H acetoxylation,16–21) our study began with attempts to acetoxylate cubane diisopropylamide 1a using a Pd(OAc)2-PhI(OAc)2 system22–26) (Table 1). Gratifyingly, monoacetoxylated cubane 2a and diacetoxylated cubane 3a were obtained using 10 mol% Pd(OAc)2, 1.2 equivalents (equiv.) of PhI(OAc)2, and 20 equiv. of acetic anhydride (Ac2O) in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) (entry 1). Similar to oxime-directed acetoxylation, other oxidants failed to produce acetoxylated compounds and instead caused degradation of 1a (entry 2). With an increased amount of Pd(OAc)2 (20 mol%), the reaction was accelerated, but no improvement in yield or selectivity was observed (entry 3). Without Pd(OAc)2, no progress of the desired reaction was observed (entry 4). Next, we screened other solvents that had previously been employed as optimized solvents for Csp3–H acetoxylation and observed a significant solvent effect. Toluene exhibited inferior reactivity and a prolonged reaction time compared to HFIP (entry 5). 1,2-Dichloroethane (1,2-DCE) showed similar reactivity to HFIP but required a prolonged reaction time (entry 6). In contrast, acetic acid exhibited improved selectivity for the mono-acetoxylated compound (2a), with a slightly longer reaction time than HFIP (entry 7). In view of the reactivity, reaction rate, and reagent handling, we concluded that HFIP was the most versatile solvent. The amount of Ac2O affected the reaction rate, requiring a longer reaction time when 10 equiv. of Ac2O were used instead of 20 equiv. (entry 8). A comparable yield was observed even in the absence of Ac2O, although the conversion of 1a was only around 70% (entry 9). In both entries 8 and 9, the formation of a black precipitate, which may be generated from Pd(OAc)2, occurred before complete consumption of starting 1a. These results indicated that Ac2O is not necessary for this reaction, but it affects the reaction rate and catalyst lifetime.

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Deviations from initial conditions | Time (h) | 1H-NMR yield (%)a) | |||

| 2a | 3a | 4a | 1a | |||

| 1 | None | 2 | 33 | 22 | 5 | 5 |

| 2 | Oxone or K2S2O8 instead of PhI(OAc)2 | 4 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| 3 | 20 mol% of Pd(OAc)2 | 1 | 32 | 20 | 5 | 8 |

| 4 | Without Pd(OAc)2 | 24 | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 98 |

| 5 | Toluene instead of HFIP | 17 | 15 | Trace | N.D. | 10 |

| 6 | 1,2-DCE instead of HFIP | 17 | 30 | 11 | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | AcOH instead of HFIP | 4.5 | 45 | 14 | Trace | 7 |

| 8 | 10 equiv. of Ac2O | 3 | 36 | 16 | 3 | 16 |

| 9 | Without Ac2O | 3 | 34 | 13 | 2 | 28 |

a) The 1H-NMR yield was determined by using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as an internal standard. N.D.: not detected.

Next, we examined how the equivalents of PhI(OAc)2 influenced the number of acetoxy groups introduced (Chart 3). As shown in Table 1, 1.2 equiv. of PhI(OAc)2 yielded a 2 : 1 mixture of mono- and diacetoxylated cubanes (2a and 3a). Doubling the amount (2.4 equiv.) produced di- and trisubstituted cubanes (3a and 4a), with only trace amounts of 2a remaining. Although 3.6 equiv. of PhI(OAc)2 did not fully convert all material into 4a, 5 equiv. predominantly yielded 4a.

With the optimized conditions established, we evaluated the scope of amide-directed acetoxylation (Chart 4). Consistent with previous reports on oxime-directed acetoxylation, the C4 substituent on the cubane significantly influenced the reaction outcome. Chlorine (1b) and bromine (1c) substitutions were tolerated, yielding mono-, di-, and triacetoxylated cubanes in moderate to high yields depending on the amount of PhI(OAc)2. The strongly electron-withdrawing cyano group suppressed cubane C–H bond reactivity, resulting in low yields of mono- and diacetoxylated cubanes (1d, 2d, and 3d). Even with 10 equiv. of PhI(OAc)2, the triacetoxylated cubane 4d was not obtained in isolable amounts.

1,4-Bis(diisopropylamide)cubane (1e) afforded reasonable yields of monoacetoxylated cubane 2e and small amounts of diacetoxylated cubane 3e with 1.2 equiv. of PhI(OAc)2. However, using additional equivalents of PhI(OAc)2 produced an inseparable mixture of multi-acetoxylated cubanes.27)

O-Tert-butyldiphenylsilyl cubylcarbinol (1f) yielded di- and triacetoxylated cubanes (3f and 4f) in low yields despite complete conversion of the starting material 1f. Notably, in our oxime-directed C–H acetoxylation experiments, similar substrates provided only trace amounts of acetoxylated products. These results suggest that amide-directed C–H activation extends the applicability of acetoxylation to electron-donating substituents.

Unfortunately, other electron-donating groups (R = Ph (1g), NHBoc (1h)) and unsubstituted cubaneamide (1i) proved incompatible with the reaction conditions, yielding complex mixtures.

In summary, we developed an amide-directed catalytic C–H acetoxylation of cubanes. This methodology represents a new strategy for cubane C–H functionalization, facilitating the discovery of novel functional molecules containing cubane scaffolds, such as drug candidates. Our group is currently expanding this approach for versatile cubane C–H bond functionalization.

This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI Grants for Early-Career Scientists (JP21K15218 and JP23K14315 to S.N.) and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (25K09866 to S.N.), the Tokyo Biochemical Research Foundation (S.N.), the Teijin Pharma Award in Synthetic Organic Chemistry, Japan (S.N.), and the Research Support Project for Life Science and Drug Discovery (BINDS) from AMED (Grant JP22ama121040j0001 to Y.I.). We deeply appreciate the late Professor Philip E. Eaton for providing the opportunity to conduct this research, his insightful suggestions, and his continuous encouragement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supplementary materials.