2021 Volume 68 Issue 6 Pages 621-630

2021 Volume 68 Issue 6 Pages 621-630

Histological classification and cytology reporting format described in General Rules for the Description of Thyroid Cancer, the 8th edition (2019) (the Japanese General Rules) were briefly introduced. Moreover, the differences between “the Japanese General Rules”, and WHO Histological Classification, the 4th edition (2017) and The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology, the 2nd edition (2018) were also explained. The Japanese General Rules did not accept the borderline lesions of thyroid tumor which were newly shown in WHO Histological Classification. We believe it is not necessary to introduce these borderline lesions in daily practice in Japan. Borderline lesions were proposed for avoiding over-surgery for thyroid cancer patients. In the United States, when the patient is diagnosed as malignant on cytology, total thyroidectomy is generally recommended. However, there is no over-surgery in Japan, because surgeons have several choices of treatment for thyroid cancer patients. This article is the first that the Japanese General Rules was shown by foreign language. Therefore, this will be advantageous to us when we present our opinion concerning histology and cytology of thyroid tumor to the world.

The nation-wide standardized terminologies and definitions of the tumors for daily medical practices are provided by the respective medical societies in Japan. For this purpose, a total number of 27 authorized monographs for tumors of various organs and sites have been published at this moment. Concerning thyroid tumors, the eight versions of General Rules for the Description of Thyroid Cancer have been published since 1977. The current version, the 8th edition, edited by Japan Association of Endocrine Surgery and The Japanese Society of Thyroid Pathology appeared in 2019 [1]. Both histological classification and cytological reporting format were basically described along the policies of the WHO Histological Classification, the 4th edition (2017) [2] and The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology, the 2nd edition (2018) (The Bethesda System) [3-5] with some exceptions.

All authors of this article are the members of Thyroid Pathology Diagnosis Consensus Meeting of the Fukushima Health Management Survey [6-8]. The Japanese Government and Fukushima Prefectural Government started Health Management Survey including thyroid ultrasound and pathological examinations in 2011 just after the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident, following the Great East Japan disaster. In this Survey, we engage on making the final histological and cytological diagnoses of the thyroid lesions of the target people. We usually use the terminologies and definitions of the “General Rules for the Description of Thyroid Cancer, the 8th edition (2019)” (the Japanese General Rules). The Japanese General Rules have some differences from WHO Histological Classification (2017) and The Bethesda System (2018).

In this article, we would like to describe the outlines of the Japanese General Rules, and point out of the differences from these internationally accepted histological and cytological standards. There is no foreign version of the Japanese General rules. Therefore, this article will promote to distribute our principal all over the world.

Histological classification of thyroid tumor appeared in the Japanese General Rules is shown in Table 1.

| 1. Benin tumors |

| a. Follicular adenoma |

| Variants |

| 1) Follicular adenoma, oxyphilic cell (oncocytic) variant |

| 2) Follicular adenoma, clear cell variant |

| 2. Malignant tumors |

| a. Papillary carcinoma |

| Variants |

| 1) Papillary carcinoma, follicular variant |

| 2) Papillary carcinoma, macrofollicular variant |

| 3) Papillary carcinoma, oxyphilic cell (oncocytic) variant |

| 4) Papillary carcinoma, diffuse sclerosing variant |

| 5) Papillary carcinoma, tall cell variant |

| 6) Papillary carcinoma, solid variant |

| 7) Papillary carcinoma, cribriform variant |

| 8) Papillary carcinoma, hobnail variant |

| 9) Other variants |

| b. Follicular carcinoma |

| 1) Follicular carcinoma, minimally invasive |

| 2) Follicular carcinoma, encapsulated angioinvasive |

| 3) Follicular carcinoma, widely invasive |

| Variants |

| 1) Follicular carcinoma, oxyphilic cell (oncocytic) variant |

| 2) Follicular carcinoma, clear cell variant |

| c. Poorly differentiated carcinoma |

| d. Anaplastic carcinoma |

| e. Medullary carcinoma |

| f. Mixed medullary and follicular cell carcinoma |

| g. Lymphoma |

| 3. Other tumors |

| a. Hyalinizing trabecular tumor |

| b. Columnar cell carcinoma |

| c. Mucinous carcinoma |

| d. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

| e. Intrathyroid thymic carcinoma (ITTC) |

| f. Spindle cell tumor with thymus-like differentiation (SETTLE) |

| g. Squamous cell carcinoma |

| h. Sarcomas |

| i. Others |

| j. Secondary (metastatic) tumors |

| 4. Unclassified tumors |

| 5. Tumor-like lesions |

| a. Adenomatous goiter |

| b. Amyloid goiter |

| c. Cyst |

All the thyroid tumors and related lesions are roughly divided into 1. Benign tumors, 2. Malignant tumors, 3. Other tumors, 4. Unclassified tumors and 5. Tumor like-lesions. Before description of characteristic findings of each lesion, we would like to show the reason why the Japanese General Rules did not accept the new categories of thyroid borderline lesions proposed by the WHO Histological Classification (2017).

Newly proposed borderline lesions are composed of as follows; (1) Follicular tumor of uncertain malignant potential (FT-UMP), (2) Well-differentiated tumor of uncertain malignant potential (WDT-UMP), (3) noninvasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP). These low-risk, encapsulated follicular epithelial tumors were separated from papillary and follicular carcinomas.

We understand that the patients with thyroid tumors diagnosed as malignant by fine needle aspiration cytology are generally recommended to receive thyroidectomy with additional radiotherapy according to the American Thyroid Association management guideline [9]. Therefore, overtreatment has become the problem in the U.S. For avoiding over-surgery, borderline lesions were proposed. However, in Japan we have several choices of treatment for the thyroid cancer patients, including follow-up without surgery [10]. Then, we have no troubles concerning overtreatment and over-surgery. We believe it is not necessary to introduce the newly proposed borderline lesions in daily medical practice in Japan, and did not describe these lesions in the histological classification of “the Japanese General Rules” [11-13]. Recently, the NIFTP working group members proposed the refined diagnostic criteria of NIFTP [14]. According to their proposal, molecular test will be mandatory for the diagnosis of NIFTP. However, most of the clinicians find it difficult to follow the procedure for diagnosing NIFTP.

The other differences between “the Japanese General Rules” and WHO Histological Classification will be presented later in each tumor category.

Follicular adenoma is a follicular epithelial benign tumor, encapsulated with fibrous capsule. Tumor cells show relatively same shape and size, and basically form follicular structures. There is no evidence of capsular invasion, vessel invasion and metastasis. There are several variants shown in Table 1.

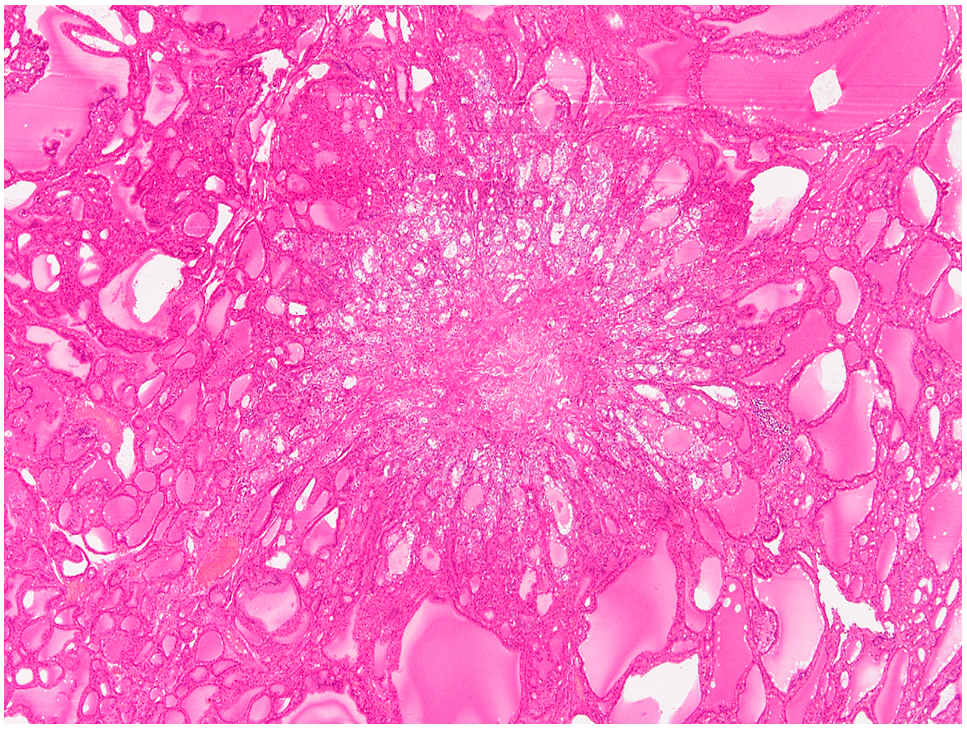

Papillary carcinoma derives from follicular epithelium. Characteristic nuclear findings are essential for diagnosis of papillary carcinoma. Important nuclear features are as follows; ground glass nucleus, overlapping nuclei, nuclear groove and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion (pseudo-inclusion) (Fig. 1). Squamous metaplasia and psammoma body also can be seen. Most of the cases show papillary structures. However, papillary structures are not necessary for making a diagnosis of papillary carcinoma. Papillary carcinoma, follicular variant, has no papillary structure in the tumor.

Papillary carcinoma.

Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions, nuclear grooves, nuclear overlapping, and clear nuclei are seen.

In some cases, solid, trabecular and/or insular structures are combined as a minor component.

There are more than eight variants of papillary carcinoma.

Follicular variant has no papillary structures in the tumor, and should be differentiated from follicular carcinoma (Fig. 2).

Papillary carcinoma, follicular variant.

Carcinoma cells with nuclear features of papillary carcinoma show follicular pattern.

In tall cell variant, tall cell means that the height of tumor cells shows more than three times comparing to the width of tumor cells (Fig. 3). When more than 50% of the tumor cells reveal tall cells, the tumor is called as tall cell variant.

Papillary carcinoma, tall cell variant.

Carcinoma cells are tall columnar, and show nuclear features of papillary carcinoma.

In solid variant, solid and/or trabecular structures should be predominant features.

Cribriform variant occurs sporadically, or accumulates in the same family. Histologically, the tumor shows follicular or cribriform fashion with no colloid in the lumen (Fig. 4a). Nuclear clearing and scattered squamoid morules are also found. Immunohistochemically, beta-catenin shows nuclear and cytoplasmic immunoreactivity (Fig. 4b).

Papillary carcinoma, cribriform variant.

a. Cribriform growth pattern without colloid is seen.

b. Carcinoma cells show nuclear and cytoplasmic immunopositivity for beta-catenin.

In hobnail variant, more than 30% of the tumors show hobnail pattern.

Most of microcarcinoma, whose diameter is less than 1 cm, are papillary carcinoma in the thyroid (Fig. 5).

Papillary microcarcinoma.

The size is less than 1.0 cm.

Follicular carcinoma is a malignant follicular epithelial tumor, and commonly forms follicular structures. More than one features among the findings of capsular invasion (Fig. 6), vessel invasion (Fig. 7) and metastasis should be histologically identified, when the tumor is diagnosed as a follicular carcinoma.

Follicular carcinoma. Capsular invasion is seen in two places.

Follicular carcinoma.

Carcinoma cell nest surrounded with endothelial cells is present in the blood vessel.

Follicular carcinoma can be divided into three types according to patterns of invasion; namely, (1) minimally invasive, (2) encapsulated angioinvasive, and (3) widely invasive. In minimally invasive type, invasion cannot be identified macroscopically. Capsular invasion is found histologically, but there is no vascular invasion. In encapsulated angioinvasive type, vessel invasion is found in or immediately outside the surrounding fibrous capsule. In widely invasive type, fibrous capsule is unclear in some cases.

Oxyphilic cell (oncocytic) variant and clear cell variant have characteristic cytoplasmic features.

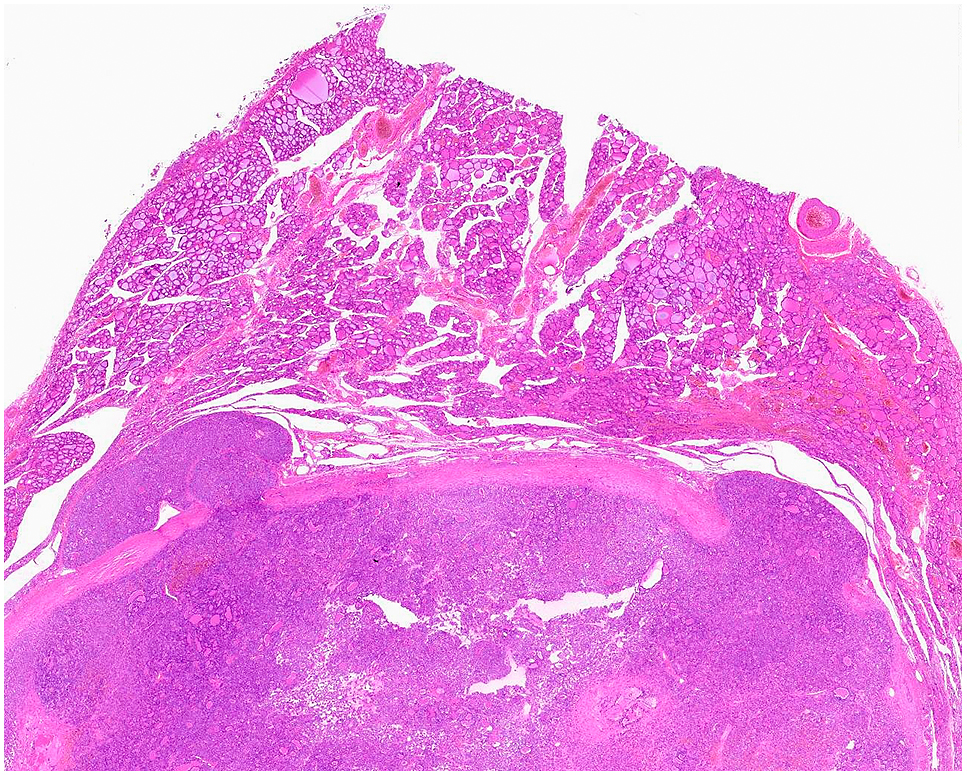

Poorly differentiated carcinomaPoorly differentiated carcinoma represents intermediate biological and histological features between well-differentiated carcinomas (papillary carcinoma and follicular carcinoma) and anaplastic carcinoma. Poorly differentiated components including solid, trabecular and insular patterns occupy more than half of the tumor (Fig. 8). Typical nuclear features of papillary carcinoma are not identified. Mitotic figures are occasionally found. Coagulation necrosis sometimes accompanied in the tumor.

Poorly differentiated carcinoma.

Insular pattern surrounded with thin fibrovascular stroma is seen.

In WHO Histological Classification (2017), the definition of poorly differentiated carcinoma accepted the Turin Proposal (2007) [15]. Namely, more than one finding of convoluted nuclei, high mitotic activity (more than 3 in 10/HPF) and tumor necrosis should be identified for a diagnosis of poorly differentiated carcinoma. However, the Japanese General Rules did not accept above mentioned definition. At least in Japan, the number of the poorly differentiated carcinoma diagnosed by the WHO Classification is quite small, and equivalent to less than 1% of all the thyroid cancer cases. Poorly differentiated carcinoma patients diagnosed by the Japanese General Rules show an intermediate prognosis between well-differentiated carcinoma and anaplastic carcinoma patients. This means reasonable results in the daily practices.

Anaplastic carcinomaAnaplastic carcinoma shows severe cellular and structural atypia with occasional necrosis and hemorrhage (Fig. 9). In some cases, papillary carcinoma, follicular carcinoma and/or poorly differentiated carcinoma components are mixed in part. These are precursor lesions, and it is called anaplastic transformation. The diagnosis of this kind of cases is designated as anaplastic carcinoma, but not mixed carcinoma.

Anaplastic carcinoma.

Large atypical cells individually proliferate. Neutrophilic infiltration is seen in the stroma.

Medullary carcinoma is a malignant thyroid tumor with C-cell differentiation (Fig. 10). Every medullary carcinoma secretes calcitonin. Both amyloid deposition and calcification frequently found. Histological and cytological findings show various features in shape.

Medullary carcinoma.

Amyloid deposition is present in the stroma.

Immunostaining of the tumor cells are positive for calcitonin, CEA, synaptophysin and chromogranin A.

Mixed medullary and follicular cell carcinomaMalignant thyroid tumor shows differentiation of both follicular epithelium and C-cell. This type of the tumor is called as mixed medullary and follicular cell carcinoma.

LymphomaMost of primary thyroid lymphomas develop in the patients with Hashimoto disease. Thyroid lymphoma is generally B-cell origin. MALT lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma are common in the thyroid.

Hyalinizing trabecular tumor is a follicular epithelium origin, and shows trabecular growth with hyalinization (Fig. 11a). Both nuclear groove and intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion are commonly found. Therefore, a misdiagnosis as papillary carcinoma should be avoided. The tumor cells show unique cell membranous immunoreactivity for MIB-1 (Fig. 11b).

Hyalinizing trabecular tumor.

a. Intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusion and yellow bodies are prominent. Hyalinized stroma is present between tumor cell nests, and even between tumor cells.

b. Tumor cells show cell membranous immunopositivity for Ki-67 (MIB-1).

Columnar cell carcinoma is classified as a variant of papillary carcinoma in WHO Histological Classification. However, columnar cell carcinoma is listed in the category of other tumors in the Japanese General Rules, because carcinoma cells lack the conventional nuclear features of papillary carcinoma.

For the differential diagnosis between primary and secondary (metastatic) tumors, immunostaining including thyroglobulin and calcitonin is useful.

Histological classification and recommended clinical management for thyroid nodules in Japan are partly different from those described in the WHO Histological Classification (2017) [2] and The Bethesda System (2018) [3-5], as we already mentioned above. Concerning thyroid cytopathology, Hirokawa, one of the authors, reported as The Japanese reporting system for thyroid aspiration cytology 2019 (JRSTAC2019) [16] as the modified version of the Bethesda System. JRSTAC2019 explained the contents of the cytological aspects of the Japanese General Rules, which is widely used in Japan.

According to the Japanese General Rules, there are seven reporting categories: 1. Unsatisfactory, 2. Cyst fluid, 3. Benign, 4. Undetermined significance, 5. Follicular neoplasm, 6. Suspicious for malignancy, and 7. Malignant (Table 2).

| 1. Unsatisfactory |

| 2. Cyst fluid |

| 3. Benign |

| 4. Undetermined significance |

| 5. Follicular neoplasm |

| 6. Suspicious for malignancy |

| 7. Malignant |

Thyroid FNA samples should be evaluated for specimen adequacy. If the samples do not fall into any of the following four scenarios representing adequacy, they are categorized as “unsatisfactory”:

1. A minimum of six groups of well-visualized follicular cells, with at least 10 cells per group

2. Abundant colloid

3. Cells with significant cytological atypia

4. Inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, plasma cells, or histiocytes

Poorly preserved specimens, including degeneration due to desiccation, poor fixation, obscuring blood, clotting artifacts and smearing failures, are also categorized as “unsatisfactory”. The reasons for categorizing specimens as “unsatisfactory” should be specified in the cytological report. A clinical recommendation for this category is a repeated aspiration. The frequency of aspirated nodules categorized as “Unsatisfactory” is recommended to be ≤10%.

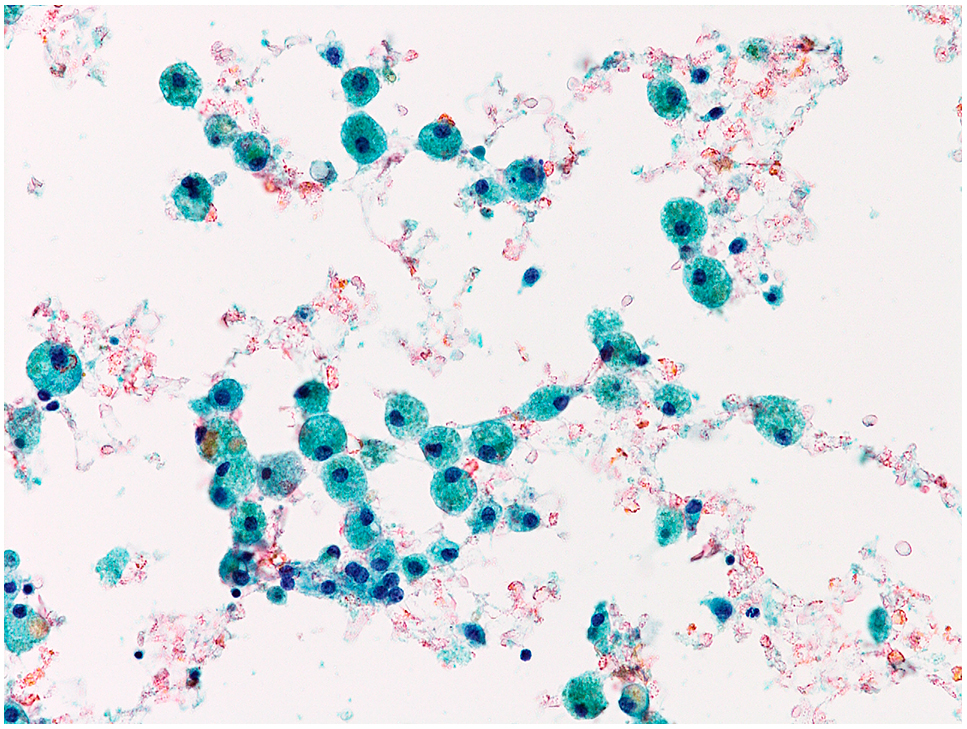

Cyst fluidThe samples obtained from cystic fluid materials are included in this category. The samples often include many foamy histiocytes (Fig. 12). Colloid materials are few or absent. If there are more than six groups with 10 benign follicular cells in the preparations obtained from cystic fluid materials, samples are categorized as “Benign”. Sonographic follow-up is recommended. If the ultrasound examination reveals a solid area in the cystic lesions, repeated fine needle aspiration cytology (FNA) for the solid area is recommended.

Cyst fluid.

Only foamy histiocytes are present.

Adequate samples with no malignant cells are categorized as “Benign”. The samples have benign follicular cells, considerable numbers of inflammatory cells, or abundant colloid materials. Materials having clusters of histiocytes without cystic fluid components are included in this category. This category includes normal thyroid, nodular goiter, colloid nodule, hyperplastic nodule, acute thyroiditis, subacute thyroiditis, chronic thyroiditis (Hashimoto thyroiditis), Riedel thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, etc. Clinical management includes follow-up. When the nodules reveal a suspicious ultrasonographic pattern, repeated FNA should be considered.

Undetermined significanceThis category includes nodules that are challenging to distinguish between benign and malignant, or nodules containing atypical cells where a possibility of malignancy cannot be excluded. They may be follicular cells, lymphoid cells, or other unknown atypical cells. These atypical cells are insufficient cellular and/or architectural atypia to be classified as “Follicular neoplasm”, “Suspicious for malignancy”, or “Malignant”. Most are possible or unexcluded papillary carcinoma cases. Follicular neoplasm-suspected nodules are not included in this category. Clinical management of this category is repeated FNA. We believe that for nodules with the possibility of medullary carcinoma or lymphoma, a measurement of serum calcitonin and flow cytometry are recommended, respectively. The recommended frequency of nodules with “Undetermined significance” is ≤10% of adequate samples.

Follicular neoplasmFollicular neoplasm refers to the nodule in which follicular adenoma or follicular carcinoma is present or suspected. Oxyphilic cell (oncocytic) type adenoma and carcinoma are also included in this category. The samples are cellular and are composed of monotonous follicular cells with a microfollicular pattern, where the follicular cells do not exhibit nuclear features of papillary carcinoma. The background is usually hemorrhagic, and a watery colloid is not observed. Oxyphilic cell type may be associated with foamy histiocytes in the background. Most nodules classified into this category are follicular adenoma or follicular carcinoma, but the benign follicular nodule, the follicular variant of papillary carcinoma, or parathyroid adenoma could also fall into this category. Repeated aspiration for the nodules classified into this category is not recommended because the possibility that the cells would change to another category with repeated aspiration is quite low. The recommended frequency of nodules with “Follicular neoplasm” is ≤10% of adequate samples.

Suspicious for malignancyNodules that are quantitatively or qualitatively insufficient for a definitive malignant diagnosis are categorized as “Suspicious for malignancy (SFM)”. This category includes various malignant tumors, and most of them are suspicious for papillary carcinoma. Hyalinizing trabecular tumor is also included in this category. Nodules suspicious of follicular adenoma and carcinoma are not included in this category. Follicular adenoma with bizarre nuclei, nodular goiter, and chronic thyroiditis may be included. Although the recommended clinical management is surgical resection, active surveillance for nodules with suggested low-risk papillary microcarcinoma is acceptable. It is recommended that more than 80% of nodules with SFM should be proved to be malignant by histological examination.

MalignantThis category is applied when the cytological features are conclusive for malignancy. It is imperative to classify the malignancy in the report, including papillary carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, medullary carcinoma, anaplastic carcinoma, metastatic carcinoma, lymphoma, etc. In papillary carcinoma nodules, the description of the variant can be beneficial in its clinical management. Although the recommended clinical management is surgical resection, active surveillance for nodules with suggested low-risk papillary microcarcinoma is also acceptable.

The terms of the categories used in the Japanese General Rules are partly different from those in The Bethesda System. The categories and abbreviations proposed by The Bethesda System are widely used across the world. The abbreviations may confuse those who are not accustomed to thyroid cytology. Also, some categories have two terms for the same cytological observation, e.g., “Atypia of undetermined significance (AUS)” or “Follicular lesion of undetermined significance (FLUS)”. To avoid such confusions, it would be better if each category could be consisted of a single term. The terms used in the Japanese General Rules are simple and have been widely accepted by Japanese cytopathologists and cytotechnologists.

Cyst fluid lesionsIn Japan, the incidence of malignancy in “Cyst fluid (CF)” lesions was extremely low (0.2%) [17], which was lower than those of Nondiagnostic/ Unsatisfactory (ND/UNS) nodules, excluding CF (5.6%) and benign nodules (1.2%) [18, 19]. Consequently, CF nodules are listed as an independent category in the Japanese General Rules. The follow-up is determined by risk stratification on ultrasound patterns, the same as for “Benign” nodules recommended by American Thyroid Association management guideline [9].

Non-invasive follicular thyroid neoplasm with papillary-like nuclear features (NIFTP)The borderline tumor entity, including NIFTP, was not adopted in the histological classification of the Japanese General Rules. Generally Japanese pathologists tended to diagnose NIFTP as a follicular adenoma [20]. According to our experiences, a total of 29.5% of the tumor diagnosed as follicular adenoma can be classified as NIFTP [20]. Cytologically, in Japan, most of the nodules equivalent to NIFTP are classified into follicular adenoma [11, 12, 21].

Risk of malignancy (ROM)ROMs in each category are affected by various factors including histological and cytological diagnostic criteria, the experience and philosophy of cytopathologists, indication of surgical excision, institutions, race, country, health care system structures, and social backgrounds. Then, ROMs were not described in the Japanese general Rules.

Clinical managementClinical management in Japan is different from that in Western countries. The recommended management of “Follicular neoplasm (FN)” nodules is surgical excision in Western countries, and the option of molecular testing is incorporated before going ahead directly to surgery [5]. In Japan, not all “FN” nodules underwent surgical resection. Half of FN nodules have been followed up without molecular testing [21]. Immediate surgery for “FN” nodules is recommended for patients with the following clinicopathological findings: cytological atypia or ultrasound findings with a possibility of malignancy, large tumor size, serum level of thyroglobulin >1,000 ng/mL, nodules strongly compressing the trachea or esophagus, nodules expanding into the mediastinum, autonomously functioning nodules or nodules with cosmetic problems. Active surveillance for adult patients with low-risk papillary thyroid microcarcinoma is the accepted treatment strategy in Japan [22]. Therefore, resection rates of SFM and malignant nodules were 57.9–64.5% and 68.3–72.1%, respectively [21]. Then, the Japanese General Rules did not adopt the clinical management recommendations of TBS. Overall, it is critical to understand that clinical management strategies between Japan and Western countries differ, resulting in different statistics.

We outlined histological classification and cytology reporting format of thyroid tumor of “General Rules for the Description of Thyroid Tumor”, the 2nd edition (2019) published by the Japanese medical societies. We also described the differences between the Japanese General Rules, and internationally spread terminologies, definitions and cytological categories of thyroid tumor. This article will help us when we would like to show our messages using the concept of “the Japanese General Rules” to the world.

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest.

This article was not supported by any funding sources.