2023 Volume 70 Issue 10 Pages 999-1003

2023 Volume 70 Issue 10 Pages 999-1003

The role of adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT) for locally advanced differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) is controversial because of the lack of prospective data. To prepare for a clinical trial, this study investigated the current clinical practice of adjuvant treatments for locally advanced DTC. A survey on treatment selection criteria for hypothetical locally advanced DTC was administered to representative thyroid surgeons of facilities participating in the Japan Clinical Oncology Group Radiation Therapy Study Group. Of the 43 invited facilities, surgeons from 39 (91%) completed the survey. For R1 resection or suspected residual disease, 26 (67%) facilities administered high-dose (100–200 mCi) radioactive iodine (RAI), but none performed EBRT. For R2 resection or unresectable primary disease, 26 (67%) facilities administered high-dose RAI and 7 (18%) performed adjuvant treatments, including EBRT. For complete resection with nodal extra-capsular extension, 13 (34%) facilities administered high-dose RAI and 1 (3%) performed EBRT. For unresectable mediastinal lymph node metastasis, 31 (79%) facilities administered high-dose RAI and 5 (13%) performed adjuvant treatments, including EBRT. Adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed mainly because of the lack of evidence for efficacy (74%). Approximately 15% of the facilities routinely considered adjuvant EBRT for DTC with R2 resection or unresectable primary or lymph node metastasis disease. Future clinical trials will need to optimize EBRT for these patients.

DIFFERENTIATED THYROID CANCER (DTC) is the most common endocrine cancer, with an increasing incidence worldwide [1]. According to the American Thyroid Association (ATA) and Japanese Society of Thyroid Surgery high-risk disease guidelines, surgery, adjuvant high-dose radioactive iodine (RAI), and thyroid-stimulating hormone suppression are standard treatments for locally advanced DTC [2, 3]. The rate of structural disease recurrence is 30%–40% when gross positive margins, gross extrathyroidal extensions, extra-nodal extensions, and metastatic lymph nodes >3 cm are present [2]. Some retrospective studies have shown evidence of long-term locoregional control using adjuvant external-beam radiotherapy (EBRT) in patients with locally advanced DTC [4-14]. From these results, adjuvant EBRT is recommended for patients with aerodigestive invasion by the ATA and for gross residual or unresectable locoregional disease by the American Head and Neck Society [2, 15]. However, there is no description of adjuvant EBRT in the Japanese Society of Thyroid Surgery, and EBRT has been recommended for alleviating the symptoms associated with advanced or recurrent DTC given that salvage surgery, RAI, or molecularly targeted drugs are not indicated [3].

The guidelines on EBRT for treating locally advanced DTC remain controversial because of the lack of results from comparative studies with a high level of evidence. Thus, to prepare for a clinical trial, the study aim was to conduct a survey to investigate current patterns of practice and use of adjuvant treatment for locally advanced DTC.

The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Radiation Therapy Study Group (JCOG-RTSG) created a survey questionnaire (Table 1) to gather information on treatment selection criteria for locally advanced DTC from representative thyroid surgeons belonging to facilities participating in the JCOG-RTSG. The survey assessed adjuvant treatments that thyroid surgeons would routinely use for hypothetical cases, the reasons why adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed, and the total numbers of patients with gross tumor margins (R2 resection) or unresectable lymph node metastasis in the recent calendar year. Case 1 describes a high-risk patient with DTC infiltrated from the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the entrance of the larynx. In case 1 with situation 1, the recurrent laryngeal nerve was resected, and the postoperative pathological margin was positive (R1 resection) or a microscopic residual tumor was suspected. In case 1 with situation 2, the recurrent laryngeal nerve was resected with R2 resection, or it was determined that the recurrent laryngeal nerve was completely unresectable. Case 2 describes a high-risk patient with DTC who had multiple lymph node metastases, including superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis behind the sternum. In case 2 with situation 1, the superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis was resected with sternotomy, and the postoperative pathological findings revealed a negative margin (R0 resection) and extra-nodal extension. In case 2 with situation 2, it was determined that the superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis was completely unresectable, and a total thyroidectomy and neck dissection were performed. The survey was sent by email to all representative thyroid surgeons belonging to facilities participating in the JCOG-RTSG at 43 facilities in February 2023. As this survey did not have access to individual patient data and all questionnaires were completed voluntarily, the requirement for Institutional Review Board approval was waived.

Survey questionnaire on adjuvant treatment for locally advanced DTC

| All questions refer to the common practice in your hospital. |

| Q1. Hypothetical cases |

| Which adjuvant treatment would you routinely perform for locally advanced differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) in Cases 1 and 2? |

| (Options: Low-dose (30 mCi) radioactive iodine (RAI)/High-dose (100–200 mCi) RAI/External-beam radiotherapy (EBRT)/Low-dose RAI plus EBRT/High-dose RAI plus EBRT/No additional treatments/Others) |

| Case 1. |

| A 50-year-old woman was diagnosed with cT4aN1bM0 stage I papillary thyroid cancer (UICC, 8th edition). The primary lesion infiltrated from the recurrent laryngeal nerve to the entrance of the larynx. She had no complications and tolerated surgery. She had no other high-risk factors (primary tumor >4 cm, metastatic lymph node >3 cm, extra-nodal extension). Her Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) was 0. |

| [Situation 1] The recurrent laryngeal nerve was resected, and the postoperative pathological margin was positive (R1 resection) or a microscopic residual tumor was suspected. |

| [Situation 2] The recurrent laryngeal nerve was resected, and the gross margin was positive (R2 resection) or the recurrent laryngeal nerve was judged to be completely unresectable. |

| Case 2. |

| A 50-year-old woman was diagnosed with cT2N1bM0 stage I papillary thyroid cancer (UICC, 8th edition). She had multiple lymph node metastases, including superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis in the sternum dorsum. She had no complications and tolerated surgery. She had no other high-risk factors (primary tumor >4 cm, metastatic lymph node >3 cm, other organ invasions). Her ECOG PS was 0. |

| [Situation 1] The superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis was resected with sternotomy, and the postoperative pathological findings were negative in the margin (R0 resection) and there was extra-nodal extension. |

| [Situation 2] The superior mediastinal lymph node metastasis was found to be completely unresectable, and total thyroidectomy and neck dissection were performed. |

| Q2. If adjuvant EBRT for locally advanced DTC is not routinely performed, what are the reasons? |

| (Options: Lack of effective response/High invasiveness/Worsening quality of life/Long treatment duration/Keeping opens the option of salvage EBRT/Lack of evidence/Already undergoing adjuvant EBRT/Others) |

| Q3. How many patients with R2 resection or unresectable lymph node metastasis from locally advanced DTC have you experienced in the recent calendar year? |

| (Options: 0/1–5/6–10/≥11) |

DTC, differentiated thyroid cancer; EBRT, external-beam radiotherapy; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; RAI, radioactive iodine; UICC, Union for International Cancer Control

In total, 39 facilities (91% of the JCOG-RTSG facilities) responded between February 2023 and March 2023. Of the respondents, 31 (79%) thyroid surgeons were specialists from the Japanese Society of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery and 8 (21%) were specialists from the Japan Surgical Society. The median number of years since becoming a doctor was 25 (range, 10–40). Among the respondents, 25 (64%) worked at university hospitals, 9 (23%) worked at cancer centers, and 5 (13%) worked at public hospitals. Additionally, 20 (51%) were RAI inpatient facilities.

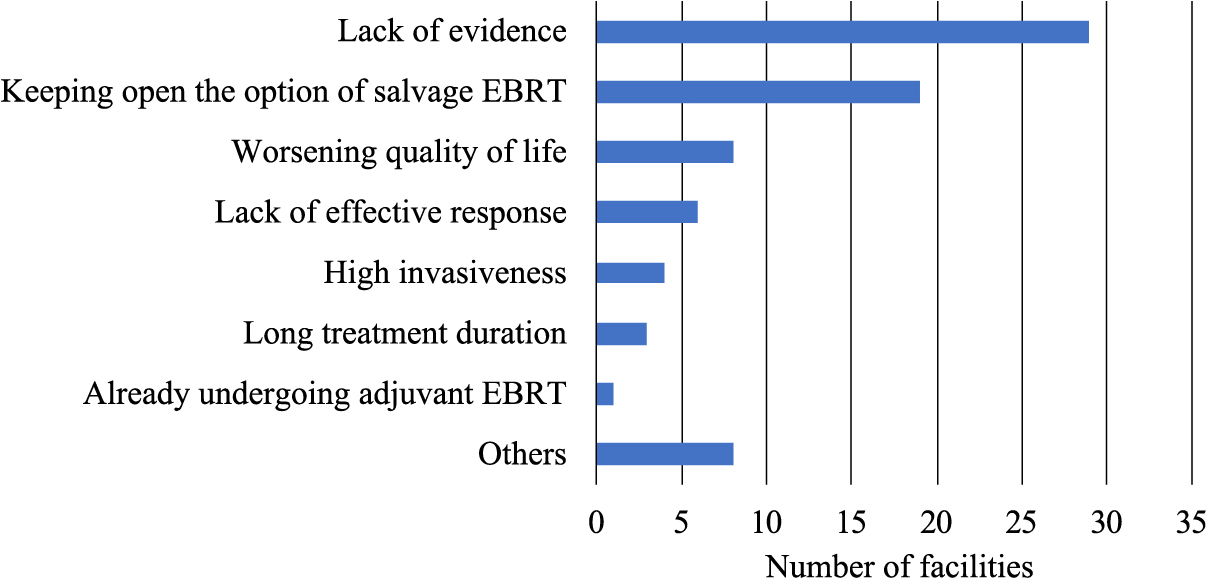

Fig. 1 presents adjuvant treatments routinely performed by thyroid surgeons for hypothetical cases. In case 1 with situation 1, 26 (67%) facilities performed high-dose (100–200 mCi) RAI, 7 (18%) performed low-dose (30 mCi) RAI, 5 (13%) performed no additional treatments, and 1 (2%) performed other treatments. The facility that chose other treatments was unsure of the dose and as a result they would refer the patients to facilities that could perform RAI. In case 1 with situation 2, 26 (67%) facilities performed high-dose RAI, 4 (10%) performed high-dose RAI plus EBRT, 3 (8%) performed low-dose RAI, 2 (5%) performed EBRT alone, 2 (5%) performed no additional treatments, 1 (3%) performed other treatments, and 1 (2%) performed low-dose RAI plus EBRT. Other treatments included laryngectomy. In case 2 with situation 1, 13 (33%) facilities performed high-dose RAI, 12 (31%) performed low-dose RAI, 11 (28%) performed no additional treatments, 2 (5%) performed other treatments, and 1 (3%) performed EBRT alone. Other treatments included multiple options (with no additional treatments or high-dose RAI). In case 2 with situation 2, 31 (79%) performed high-dose RAI, 4 (10%) performed high-dose RAI plus EBRT, 3 (8%) performed other treatments, and 1 (3%) performed low-dose RAI plus EBRT. Other treatments included molecularly targeted drugs (in case of occurrence of disease progression). Fig. 2 presents the reasons given by surgeons for why adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed. The primary reason was the lack of evidence for efficacy (74%). Other reported reasons were keeping open the option of salvage EBRT (49%), worsening of quality of life (QOL) (21%), lack of effective response (15%), high invasiveness (10%), long duration of treatment (8%), already undergoing adjuvant EBRT (3%), and others (7%).

Hypothetical cases for adjuvant treatments.

EBRT, external-beam radiotherapy; RAI, radioactive iodine

The reasons given for why adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed.

EBRT, external-beam radiotherapy

The numbers of patients who underwent R2 resection or unresectable lymph node metastasis from locally advanced DTC per year were 0 for 8 facilities, 1–5 for 30 facilities, and ≥11 for 1 facility.

The survey described in this report further clarified the availability of adjuvant treatments for the management of locally advanced DTC and was able to obtain the responses of most facilities belonging to the JCOG-RTSG.

If EBRT is not performed at all facilities, there is no need for EBRT, and the value of conducting clinical trials is low. Whereas, if EBRT is routinely performed at all facilities, EBRT is considered as the standard treatment despite the lack of clinical trials. Therefore, the current study aimed to identify cases in which the use of EBRT differed between facilities. Our results revealed that among all 39 facilities that were analyzed, 7 (18%) and 5 (13%) performed adjuvant treatments, including EBRT, for R2 resection or unresectable primary disease and for unresectable mediastinal lymph node metastasis, respectively. Although only a few centers opted for EBRT, we believe it was worthwhile to conduct a clinical trial for these cases. Our previous study demonstrated that R2 resection was an independent prognostic factor for locoregional recurrence-free survival and that adjuvant RAI plus EBRT improved locoregional recurrence-free survival versus RAI alone with propensity score matching [13, 16]. Consequently, we expected that at the time of survey planning, there would be increased demand for EBRT for R2 resection or unresectable cases, and the survey results were consistent with expectations. On the other hand, it was concerning that R2 resection or unresectable cases were rare in daily clinical practice. However, a few cases were experienced at many institutions.

We found that adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed primarily because of the lack of evidence for efficacy. These results suggested that there was a demand for adjuvant EBRT for R2 resection or unresectable cases by thyroid surgeons, and that if sufficient evidence can be established, adjuvant EBRT will be increased in clinical practice.

Adjuvant EBRT also was not routinely performed because the surgeons wanted to keep open the option of salvage EBRT. Lamartina et al. reported the risk factors for hemoptysis in patients with thyroid cancer during tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment [17]. Hemoptysis was associated with the presence of airway invasion and a history of therapeutic EBRT, including salvage EBRT (not adjuvant EBRT). Patients who did not receive EBRT exhibited a lower risk of hemoptysis (3%) than those who received adjuvant EBRT (7%) (p = 0.3), whereas those who received therapeutic EBRT carried the highest risk of hemoptysis (31%) (p = 0.003). This result suggested that it is better to use adjuvant EBRT rather than salvage EBRT for DTC patients who will receive tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment.

The third reason explaining why adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed was the worsening of QOL. Hedman et al. reported lower health related QOL scores in the areas of physical functioning, general health, vitality, social functioning, and mental health for patients with recurrent DTC than for patients without [18]. The importance of preventing disease recurrence is demonstrated by the fact that even patients without recurrence fear it to the extent that it lowers QOL scores in the areas of general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role functioning, and mental health. Moreover, Romesser et al. reported no differences in oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal domain-specific modified barium-swallow study scores assessed before and after EBRT [19]. These results suggested that adjuvant EBRT to prevent recurrence was considered better for preserving QOL for high-risk DTC patients.

Some facilities without RAI inpatient facilities did not perform high-dose RAI on high-risk patients with DTC. The lack of medical facilities for RAI has become one of the most important medical issues in Japan because RAI is performed in limited numbers of medical facilities associated with strict regulation of radioactive substances [20]. The Japanese Society of Nuclear Medicine is currently promoting the implementation of adjuvant RAI in outpatient settings.

Our survey had a limitation that should be considered. Adjuvant treatments for hypothetical cases might not accurately reflect clinical management. In particular, the definition of unresectable varies according to the institution and surgical skills. Therefore, we attempted to present the information on resection as a situation for hypothetical cases. However, it is extremely important to understand practice patterns, and the survey findings will be considered in future clinical trials.

In conclusion, approximately 15% of facilities routinely considered adjuvant EBRT for DTC with R2 resection, unresectable primary, or lymph node metastatic disease. Adjuvant EBRT was not routinely performed primarily because of the lack of evidence for its efficacy. The results of this survey indicated that there is scope for considering the eligibility for EBRT, which supports conducting a clinical study to optimize EBRT use in future trials.

We are grateful to all the co-investigators in the Radiation Therapy Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group and the survey respondents for their cooperation in filling out the questionnaire survey. We thank Dr. Takeshi Kodaira for his useful discussions.

TK prepared the manuscript and conducted the literature search; TK reviewed and edited the manuscript; and TK, KY, YI, SZ, KS, NS, NN, and TM reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (22K07779) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan.

Conflict of interestDr. Mizowaki received honoraria from Varian Medical Systems, Hitachi Ltd., Brainlab AG, and Elekta KK outside the submitted work. Dr. Mizowaki belongs to leadership position in Japanese Society for Radiation Oncology, Japan Radiological Society, Japan Society of Clinical Oncology, and Japan Society of Urologic Oncology. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.