2023 Volume 70 Issue 3 Pages 275-280

2023 Volume 70 Issue 3 Pages 275-280

Hyperandrogenism is a state of androgen excess that can induce hirsutism and oligo/amenorrhea in women of reproductive age. Therapeutic strategies differ according to etiology. Hence, the differential diagnosis of hyperandrogenism is crucial. The adrenal gland is an important organ that produces androgens. One common cause of hyperandrogenism is androgen-secreting adrenal tumors; however, adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasms (ACONs) are rare. A 23-year-old woman presented with severe hirsutism and menstrual disorders for 2 years. Her Ferriman-Gallway hirsutism score was 15 at her first consultation. Her menstrual cycles were irregular, and her menstrual flow had diminished gradually over the past 2 years. She had a remarkable elevation of total testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate and androstenedione. Pelvic ultrasonography showed normal morphology of the uterus and bilateral ovaries. Computed tomography revealed a giant left adrenal tumor with a diameter of 12 cm. The patient then underwent robotic-assisted adrenal tumor resection. Histopathological assessment indicated adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential. After 4 years of follow-up, no recurrence of symptoms was noted, and this patient delivered a healthy infant on her due date in October 2021. This article reviews the clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment of ACONs and highlights the importance of differential diagnosis for hyperandrogenism in women.

HYPERANDROGENISM is a state of increased androgen production and is one of the most common endocrine disorders among reproductive-aged women, with a prevalence of 5–10% [1]. Cardinal clinical manifestations include hirsutism, acne and oligo/amenorrhea. Other symptoms of virilization, such as androgenic alopecia, deep voice and clitoral enlargement, may occur when androgen levels are greater than 2.5 times above the physiologic level [2]. There are multiple causes of hyperandrogenism, such as polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), androgen-secreting tumors, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), idiopathic hirsutism and iatrogenic causes [3, 4]. Therapeutic strategies differ according to their etiology. Hence, the differential diagnosis of hyperandrogenism is crucial for determining subsequent management.

In this case, a young woman presented with severe hirsutism and menstrual irregularity; her serum testosterone level was elevated 7.3-fold, and radiological imaging revealed a large left adrenal tumor. After robotic-assisted adrenal tumor resection, the histopathological findings confirmed the diagnosis of adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasm (ACON) with uncertain malignant potential. Since such cases are rare and complicated, a thorough preoperative investigation and multidisciplinary management are needed; in addition, regular follow-up, including clinical, biochemical and radiological monitoring, is also essential.

A 23-year-old woman presented to the gynecological endocrinology outpatient clinic of our hospital with progressive symptoms of hirsutism and menstrual disorders for 2 years. She attained menarche at the age of 14 and had regular menstrual cycles. The onset of menstrual irregularity occurred in 2016, her cycles were anywhere from 15 days to 4 months, and the menstrual flow diminished gradually. She also had increased hair growth on her face, abdomen, perineum and upper thighs. She complained of recurrent facial acne and had undergone laser treatment. She denied a history of voice deepening or hair loss. In August 2017, she visited a traditional Chinese medical hospital for menstrual disorders. Her testosterone level was 17.51 nmol/L, a pelvic ultrasonography was normal, and she was administered traditional Chinese medicine for 2 months, but her menstrual periods were still irregular. She then presented to our hospital with amenorrhea for 4 months in February 2018. The patient had no pertinent previous medical or familial history.

A physical examination revealed marked hirsutism with a Ferriman-Gallway hirsutism score of 15 (upper lip 2, chin 1, upper chest 1, upper abdomen 2, suprapubic 2, anterior arms 2, anterior thighs 3, upper back 1, lower back 1). She had slight facial acne but no significant moon face, buffalo hump or acanthosis nigricans. Her blood pressure was normal, and her body mass index was 22.5 kg/m2.

She had a remarkable elevation of total testosterone (18.92 nmol/L), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS, >1,000 μg/dL) and androstenedione (>10 ng/dL), and her sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) had declined to 13.3 nmol/L. Other laboratory data, including follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol, progesterone, thyrotropin, prolactin, 17-hydroxyprogesterone, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, 8 AM plasma cortisol and 24-hour urinary free cortisol, were all within normal limits.

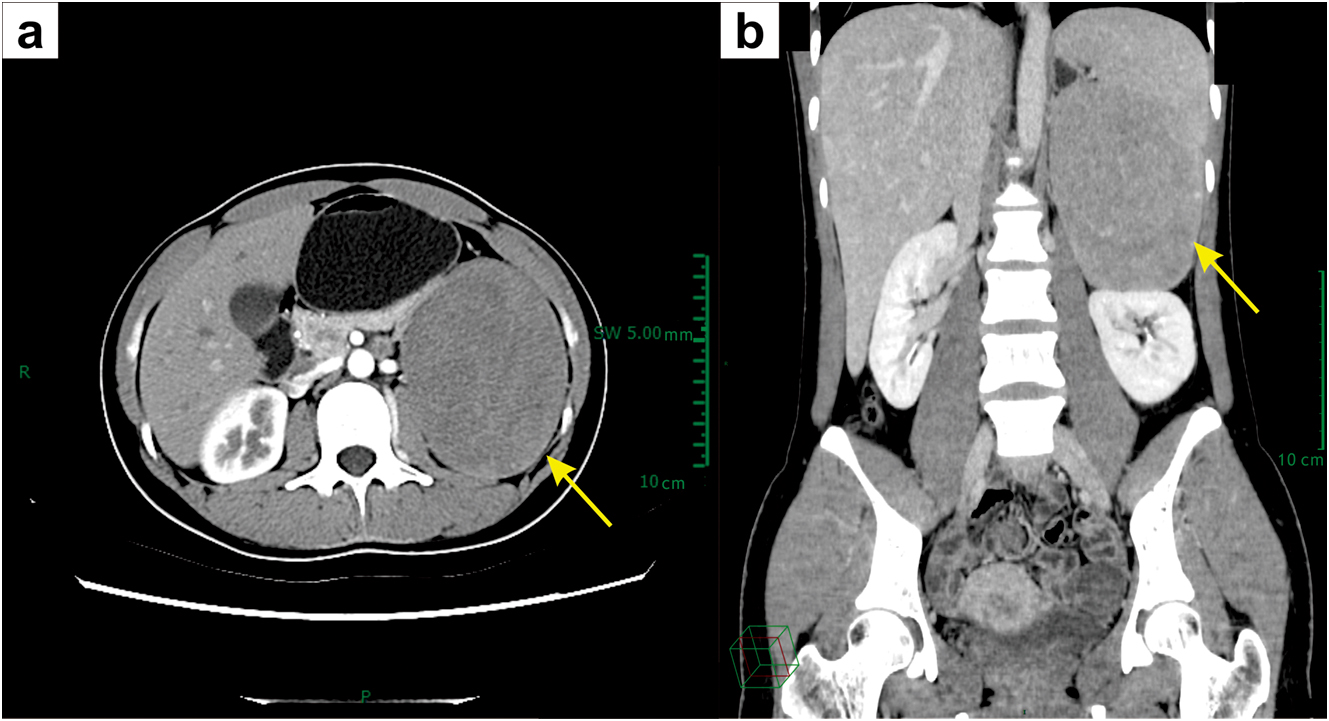

Pelvic ultrasonography showed normal morphology of the uterus and bilateral ovaries. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a left adrenal mass with a diameter greater than 10 cm (Fig. 1). Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and chest CT were normal.

Abdominal CT images. (a) Axial and (b) coronal CT images show a large heterogeneous left adrenal mass (yellow arrows).

After a preoperative multidisciplinary consultation, the patient then underwent robotic-assisted adrenal tumor resection on March 26, 2018. The histopathological assessment indicated a solitary tumor 12.0 × 9.0 × 7.0 cm, and the cross-section was gray-yellow. Microscopically, the tumor cells contained abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and focal necrosis, the mitotic rate was less than 5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields, and neither atypical mitoses nor venous invasion were observed. The non-neoplastic part of the adrenal gland demonstrated cortical atrophy due to the compression of the large tumor (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed immunopositivity for Synaptophysin, Inhibin, Melan-A, CYP11A1, DHEAST and HSD3B2, but negativity for CgA, CYP11B1, CYP11B2 and S-100. The Ki-67 labeling index was 5%, and the Reticulin network was preserved (Fig. 3a–i, 3k–m). Additionally, we performed immunohistochemical staining for P450c17α to evaluate the hormonal activity of the resected adrenal tumor. The results showed that the tumor stained positive for P450c17α (Fig. 3j), indicating that it could have the capacity to produce androgen in situ. Based on these findings, the final diagnosis of the presented case was adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential (For the antibodies used for immunohistochemistry, refer to Supplementary Table).

Histopathological assessment of the resected adrenal tumor. (a) Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows oncocytic cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm; (b) focal necrosis in the tumor; (c) non-neoplastic part of adrenal gland demonstrates cortical atrophy (indicated by red arrow); (d) an amplified area of non-neoplastic part of adrenal gland in panel c.

Immunohistochemical staining of the resected adrenal tumor. (a) Synaptophysin (+); (b) Inhibin (+); (c) Melan A (+); (d) CgA (–); (e) CYP11B1 (–); (f) CYP11B2 (–); (g) S-100 (–); (h) Ki-67 labeling index is 5%; (i) Reticulin network preserved; (j) P450c17α (+) (200×); (k) DHEAST (+); (l) CYP11A1 (+); (m) HSD3B2 (+).

No adjuvant therapies were administered afterward. One month after surgery, she underwent a hormone test, and all of her values had returned to normal (Table 1). Her periods resumed on April 22, 2018, and her menstrual cycles became regular. No recurrence of symptoms was noted at the 4-year follow-up. She delivered a 3.3 kg male infant on her due date on October 28, 2021.

| Reference range | Pre-surgery | Post-surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | 0.35–2.6 nmol/L | 18.92 nmol/L | 2.45 nmol/L |

| Androstenedione | 0.3–3.5 ng/dL | >10 ng/dL | 2.72 ng/dL |

| DHEAS | 80–560 μg/dL | >1,000 μg/dL | 203.8 μg/dL |

| 17-hydroxyprogesterone | 0.15–3.1 ng/mL | 1.80 ng/mL | 2.72 ng/mL |

| 24-hour urinary free cortisol | 21–111 μg | 39.75 μg | 42.98 μg |

| 8 AM plasma cortisol | 185–624 nmol/L | 340.71 nmol/L | 293.58 nmol/L |

| Fasting glucose | 3.90–6.10 mmol/L | 4.10 mmol/L | 5.11 mmol/L |

| Fasting insulin | 2.60–24.90 μIU/mL | 4.01 μIU/mL | 8.64 μIU/mL |

| SHBG | 18–114 nmol/L | 13.3 nmol/L | 29.6 nmol/L |

| LH | 2.12–10.89 IU/L | 5.89 IU/L | 4.85 IU/L |

| FSH | 3.85–8.78 IU/L | 4.57 IU/L | 3.01 IU/L |

| Estradiol | 99.1–447.9 pmol/L | 591 pmol/L | 245.9 pmol/L |

| Progesterone | 0.99–4.83 nmol/L | 13.43 nmol/L | 3.03 nmol/L |

| Thyrotropin | 0.27–4.2 mIU/L | 3.69 mIU/L | 2.22 mIU/L |

| Prolactin | 3.34–26.72 ng/mL | 16.11 ng/mL | 17.65 ng/mL |

Abbreviations: DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate; SHBG, sex hormone-binding globulin; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone

Hyperandrogenism is a relatively common problem that can cause hirsutism, acne, menstrual disorders and infertility. Other symptoms of virilization, such as deepening of the voice, androgenic alopecia and clitoromegaly, may occur when androgens are highly elevated. Determination of the etiology is crucial to guide clinical therapy. The etiology of hyperandrogenism in women can be divided into ovarian origin, adrenal origin, iatrogenic and idiopathic.

The ovarian causes include PCOS, androgen-secreting ovarian tumors and ovarian hyperthecosis. PCOS is the most common endocrinological disorder in reproductive-aged women, with an incidence of 8%–13% [5]. Hyperandrogenism is an important diagnostic criterion for PCOS. However, symptoms of virilization are uncommon in PCOS patients, as the serum androgen levels are generally only elevated mildly to moderately. If serum testosterone levels are elevated more than 2.5-fold the upper limits of normal, pelvic ultrasonography or MRI should be performed to exclude androgen-secreting ovarian tumors, including Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors, steroid cell tumors, granulosa cell tumors, etc. [2]. The typical clinical manifestation is a rapid onset of hirsutism and virilization. Another rare cause of ovarian-derived hyperandrogenism is ovarian hyperthecosis, which is characterized by the presence of luteinized theca cells in the ovaries that secrete androgens. It is typically associated with severe hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance. Ultrasonography often shows enlarged, round-shaped, homogenous ovaries. It is difficult to distinguish it from PCOS, and the diagnosis is established by the pathological assessment of the resected ovarian tissues [6].

The adrenal causes include CAH, androgen-secreting adrenal tumors and Cushing’s syndrome. CAH is a group of autosomal recessive diseases that cause enzyme deficiencies in the adrenal steroidogenesis pathways. The majority of CAH cases are due to 21-hydroxylase deficiency, presenting as decreased cortisol and aldosterone levels but increased androgen levels. An elevated 17-hydroxyprogesterone concentration above 300 nmol/L (10,000 ng/dL) is helpful in confirming the diagnosis of 21-hydroxylase deficiency [7]. Androgen-secreting adrenal tumors are relatively rare, and more than 50% are malignant. They can cause rapid hirsutism and virilization (in a few months) with extremely elevated DHEAS, androstenedione, and testosterone levels [8, 9]. Imaging of the adrenal glands, including ultrasonography, CT and MRI, is required to detect and assess adrenal tumors. Cushing’s syndrome, especially the ACTH-dependent form (pituitary or other ectopic ATCH tumors), should be considered when high levels of cortisol and androgens coexist. The increased ACTH stimulates the adrenal zona reticularis to produce excess androgens and cause their related clinical symptoms. Other dominant clinical manifestations are central obesity, moon face, purple skin striae and proximal limb atrophy. Elevated 24-hour urinary free cortisol can be used for screening in Cushing’s syndrome [10].

The administration of exogenous androgens and some medications, such as nortestosterone-derived synthetic progestogens, anticonvulsants, ACTH analogs, and valproate, can cause iatrogenic hyperandrogenism. Therefore, a detailed medical history is important to define the etiology. Idiopathic hirsutism accounts for 10% of hyperandrogenism cases and is considered a diagnosis of exclusion. It is characterized by regular menses, normal morphology of the ovaries and normal androgen levels. Excess hair growth may be related to the enhancement of 5α-reductase activity in the skin, which can promote the production of dihydrotestosterone. Additionally, an augmentation of androgen receptor activity may also contribute to hirsutism progression [11]. Other etiologies, such as hyperprolactinemia, pregnancy, menopause and stress, may also cause hyperandrogenism.

In this case, severe hyperandrogenism was the prominent symptom; her testosterone and androstenedione levels were increased 7.3-fold and 2.9-fold the upper limits of normal, respectively, and her DHEAS was greater than 1,000 μg/dL. Thus, androgen-secreting tumors should have been considered first. Pelvic ultrasonography revealed normal morphology of the ovaries, while adrenal gland imaging indicated a large left adrenal tumor. The diagnosis was delayed at her first consultation in the traditional Chinese medical hospital because her extraordinary elevation of androgens was neglected. In general, a DHEAS level greater than 800 μg/dL is strongly suggestive of adrenal androgen-secreting tumors, and adrenal imaging examinations are essential in such a case.

Adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasmsAdrenocortical oncocytic neoplasms (ACONs) are extremely rare adrenal cortical tumors, and to our knowledge, only 227 cases have been reported in the English literature [12]. They are usually identified incidentally, and most of them are regarded as benign and nonfunctional. However, up to 20% of ACONs can secrete one or a mixture of hormones, such as cortisol, aldosterone and androgens [13]. ACONs are usually quite large, with an average diameter of 8.4 cm. Imaging examinations have limited value for discriminating between benign and malignant tumors, but surgical resection is commonly recommended due to the large size of ACONs.

The final diagnosis of ACONs depends on its histopathological assessment. Microscopically, the tumors consist of large polygonal cells with abundant eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm. The Lin-Weiss-Bisceglia (LWB) criteria, proposed by Bisceglia in 2004, are used to differentiate between benign and malignant ACONs. There are three major criteria: (1) a mitotic rate of more than 5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields, (2) atypical mitoses, and (3) venous invasion. If any of these major criteria exist, the tumors are classified as malignant. If no major criteria are present, the minor criteria for borderline malignancy must be evaluated: (1) large size (>10 cm and/or >200 g), (2) necrosis, (3) capsular invasion, and (4) sinusoidal invasion. Benign tumors can be diagnosed in the absence of all of the aforementioned criteria [14]. In this case, no major criteria were observed, but two minor criteria (large size and necrosis) were present, so it was considered to have an uncertain malignant potential. In addition to the accepted diagnostic algorithms, immunostaining for Ki-67 and reticulin network can be useful, with adenomas showing a Ki-67 proliferation index of <5% and carcinomas of >5%. Adenomas display a preserved reticulin network, while carcinomas demonstrate an altered network [15]. This tumor displayed a Ki-67 labeling index of 5%, which was intermediate between adenoma and carcinoma, but reticulin staining showed a preserved reticulin network, indicating that this tumor was less likely to be a carcinoma. Taken together, these results suggested that this adrenocortical tumor had an uncertain malignant potential.

The prognosis of ACONs depends on the LWB diagnosis. The 5-year overall survival for benign ACONs is 100%, borderline 88% and malignant 47%. The recurrence rate is 16%, with a median time to recurrence of 18 months after initial diagnosis [13]. In one case, recurrence was diagnosed 11.5 years after the initial diagnosis [16], so long-term follow-up is necessary for our patient.

In conclusion, identifying the etiology of hyperandrogenism in women is critical for therapeutic decision-making. A complete history, a thorough physical examination, and complete biochemistry and imaging assessments are fundamental to pinpointing the exact causes of hyperandrogenism. This article reports a case of an extremely rare borderline adrenocortical oncocytic neoplasm that caused severe hyperandrogenism and oligo/amenorrhea in a young woman. Although surgical resection was curative, long-term follow-up and a thorough clinical, hormonal and imaging evaluation are required because recurrence may occur.

The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for their cooperation.

BZ and GH were the patient’s gynecological endocrinologists; BZ reviewed the literature and contributed to manuscript drafting; HW performed the histopathological analyses and contributed to manuscript drafting; DW and GH were responsible for revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; all authors issued final approval for the version to be submitted.

The literature retrieval was supported by funding from Shanghai Jiao Tong University, No. ZH2018QNA43, and English language editing was supported by funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, No. 82102123 and Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, No. 21ZR1438600.

The authors obtained informed consent from the patient to share data and images.

None of the authors have any potential conflicts of interest associated with this research.