2012 年 62 巻 4 号 p. 340-347

2012 年 62 巻 4 号 p. 340-347

The relationship between characterictics of flour of common wheat varieties and fresh pasta-making qualitites was examined, and the fresh pasta-making properties of extra-strong varieties that have extra-strong dough were evaluated. There was a positive correlation between mixing time (PT) and hardness of boiled pasta, indicating that the hardness of boiled pasta was affected by dough properties. Boiled pasta made from extra-strong varieties, Yumechikara, Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259, was harder than that from other varieties and commercial flour. There was a negative correlation between flour protein content and brightness of boiled pasta. The colors of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of standard manuring culture were superior to those of boiled pasta made from other varieties. Discoloration of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture was caused by increase of flour protein content. On the other hand, discoloration of boiled pasta made from Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture was less than that of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara. These results indicate that pasta made from extra-strong wheat varieties has good hardness and that Hokkai 262 has extraordinary fresh pasta-making properties.

“Pasta” is a general term for fresh or dried dough with various shapes, e.g., spaghetti and macaroni. It is usually made from durum wheat, and it has a very elastic texture. The production of pasta began about 100 years ago in Japan and production increased after the Second World War. Annual production of pasta in Japan is now about 290,000 t (Japan Pasta Association 2012) and pasta is now a major part of the diet in Japan. Pasta was made from common wheat flour for bread in the early period of pasta production in Japan because imports of durum wheat were restricted. Pasta made from common wheat had a weak texture in comparison with that made from durum wheat. However, a large percentage of pasta in Japan is now made from durum semolina because import of durum wheat has been deregulated and consumers now demand high-quality pasta (Tsukamoto 2000).

It is known that protein content and gluten properties are important for pasta-making properties (Matsuo and Irvine 1970, Matsuo et al. 1972). D’Egidio et al. (1990) concluded that it is a valid goal for breeding to improve the intrinsic characteristics of durum wheat varieties by enhancing the protein content and gluten quality. Mariani et al. (1995) reported that pasta properties were determined by additive effects of the environment for protein content and genotype for gluten quality.

HMW-GSs (high molecular weight glutenin subunits), which are encoded by Glu-A1 and Glu-B1, have been reported to affect dough strength and pasta-making properties using durum wheat that lacks the D genome. Pogna et al. (1990) reported that HMW-GS 7 + 8 gave higher elastic recoveries to gluten than did subunits 6 + 8 and 20. Kovacs et al. (1993) reported that a higher pasta disc viscoelasticity (PDV) value, an important indicator of pasta quality, was associated with HMW-GS 6 + 8. LMW-GSs (low molecular weight glutenin subunits), which are encoded by Glu-A3 and Glu-B3, also affect dough quality and pasta-making properties. Callio et al. (2000) showed that LMW-GSs were the most important prolamins influencing pasta quality. Durum wheat is classified into ‘LMW-1’ and ‘LMW-2’ types based on gel-resolution patterns of LMW-GSs. The dough of ‘LMW-2’ type durum wheat is more viscoelastic (stronger) than that of ‘LMW-1’ type and ‘LMW-2’ allele gives better pasta-making properties (Pogna et al. 1990, Kovacs et al. 1995). Ponga et al. (1990) reported that the positive effects of LMW-2 glutenin subunits and HMW-GS 7 + 8 on pasta-making properties were additive. Nieto-Taladriz et al. (1997) showed that the LMW-2 allele are corresponded to the allelic nomenclature of LMW-GSs by Gupta et al. (1990) and that LMW-2 glutenin subunits is mixture of various subunits encoded by different alleles at Glu-A3 and Glu-B3 loci.

The characteristics of starch have also been reported to affect the properties of noodles, including white salted noodles (WSN), yellow alkaline noodles (YAN) and pasta noodles. Ishida et al. (2003) reported that WSN made from flour of single-null type, which lacks either the Wx-B1 or Wx-D1 protein, and flour of double-null types, which lacks both the Wx-A1 and Wx-D1 proteins, had desirable texture. Ito et al. (2007) examined the relationship between starch properties and physical properties of YAN, and they showed that a variety having low amylose content had high elasticity and smoothness. For fresh pasta noodles using common wheat, Maeda (2009) reported that waxy wheat flour increased the viscous and sticky textures of boiled noodles and that high-amylose wheat flour suppresssed the damage of noodles during boiling, resulting in properties similar to those of durum pasta. Colors of noodles are also an important characteristic. Durum pasta with low brownness and high yellowness is preferable in the world market (Royo et al. 2005).

In a previous study (Ito et al. 2011) on common wheat, we found a relationship between allelic variations on three important loci (Glu-D1, Glu-A3 and Glu-B3) and dough strength. Common wheat lines with appropriate allelic combinations of the loci have extremely strong dough properties, and bread loaves made from the extra-strong lines were smaller than those made from strong lines. However, we expect that these extra-strong common wheat materials would be useful for fresh pasta-making because fresh pasta needs to have a very elasitic texture, with which a strong dough property is correlated. Pasta-making using domestically produced extra-strong common wheat would have an impact in the Japanese food market since no durum wheat varieties are cultivated in Japan. The relationship between dough peoperties of extra-strong wheat and pasta-making quality has not been investigated in previous studies. In the present study, we examined the relationship between characteristics of common wheat varieties including extra-strong varieties and fresh pasta-making properties and we evaluated the properties of extra-strong varieties for fresh pasta.

We used flour of four hard winter wheat varieties, flour of two hard spring wheat varieties and commercial flour for pasta. Seeds of the four winter varieties, Yumechikara, Kitanokaori, Hokkai 259 and Hokkai 262, were sown in late September 2008 in the research field at the National Agricultural Research Center for Hokkaido Region, Memuro, Hokkaido. These varieties were grown in an experimental plot consisting of 8 rows with length of 5 m and width of 15 cm under standard field management conditions, except for nitrogen fertilization. We used two methods of nitrogen fertilization for cultivation of Yumechikara and Hokkai 262: standard manuring culture for hard wheat varieties in Hokkaido (5-6-0-0 kgN/10 a: basal dressing-topdressing at regrowing stage-topdressing at flag leaf stage-foliar application after flowering stage) and heavy manuring culture (5-6-6-3 kgN/10 a).

Wheat samples of the four winter wheat varieties harvested in the experimental field were milled with a Buhler test mill (Buhler Inc., Uzwil, Switzerland). The flour of the two spring wheat varieties, Haruyokoi and Haruyutaka and commercial flour for pasta (blended flour of common wheat flours) were prepared by Ebetsu Flour Milling Co., Ltd., Ebetsu, Japan.

Protein content was measured using a near-infrared reflectance instrument (Inframatic 8120, Percon Co., Hamburg, Germany). Amylose content was measured by starch-iodine starch reaction. One hundred mg of wheat flour was applied to the ‘Auto Analyzer III’ system (BL TEC K. K., Japan) based on a method described by Juliano (1971) and then absorbance at 600 nm of each sample was measured. To calculate amylose content, the waxy wheat variety ‘Mochihime’ was regarded as amylopectine (0% amylose), and flour blends of Mochihime and 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30% amylose (type III: from potato, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were assayed and then a calibration curve was produced from the absorbance. The calculated content was adjusted for 13.5% water-content base. Mixing peak time (PT) was measured using a 2-g mixograph (National Manufacturing Division of TMCO, Lincoln, NE, USA).

The measurements of protein content, amylose content and dough properties were carried out in duplicate.

Glutenin preparationThe extraction solution (ES) consisted of 50% (v/v) 1-propanol and 0.08 M Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Albumin, globulin and gliadin fractions were extracted from ground flour (30 mg) in 600 μl of ES by incubating at 60°C for 30 min with gentle shaking (36 rpm). After a brief centrifugation (18,000 × g, 20°C), the supernatant was removed. This extraction was repeated three times. The glutenin fraction was extracted by resuspending the pellet in 150 μl of ES containing 60 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) at 65°C for 1 hr. After centrifugation, the supernatant (glutenin fraction) was alkylated by adding an equal volume of ES containing 1.4% vinyl-pyridine (v/v) to the supernatant. After incubation at 65°C for 30 min, 1.2 ml of acetone was added to the alkylated fraction. After centrifugation, the pellet was dried at 60°C.

Determination of Glu-1, Glu-3 and Wx-1 genotypesThe genotypes (alleles) of Glu-A1, Glu-B1 and Glu-D1 (HMW-GSs) in each variety were determined by performing SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and comparing the resolution patterns to those shown in the catalogue by Payne and Lawrence (1983). The glutenin pellet was dissolved in 100 μl of sample buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS and 0.002% (w/v) bromophenol blue (BPB). The glutenin solution was subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained using a coomassie brilliant blue (CBB) solution (0.25% (w/v) CBB, 45% (w/w) methanol and 10% (w/w) acetic acid).

The genotypes of Glu-A3, Glu-B3 and Glu-D3 were determined by performing SDS-PAGE and 2-dimensional (2D)-PAGE and by comparing the resolution patterns to that of each allele shown by Gupta and Shepherd (1990), Ikeda et al. (2006) and Jackson et al. (1996). The 2D-PAGE analysis was performed following the method described by Ikeda et al. (2006).

The genotypes of Wx-A1, Wx-B1 and Wx-D1 were determined using PCR assay for detecton of null alleles of the waxy genes, as described by Nakamura et al. (2002).

Preparation and mechanical measurement of fresh pastaThe ingredients of fresh pasta were 100 g wheat flour, 50 g egg and 2 g salt. All of the ingredients were mixed by a food processor (MK-K80P-W, Panasonic Corporation, Osaka, Japan) for 1 min and then the dough was pushed out through a dice with holes of 2 mm in diameter by high pressure using a pressing noodle machine (Kikouti-meijin, Ohotsuku-buturyu Co., Ltd., Abashiri, Japan). The noodles produced by pressing were cut into strips of approximately 20 cm in length using kitchen scissors. Raw noodle strips were cooked in 3 L of boiling water for 7 min and rinsed in a water bath at 20°C for 1 min. Water on the surface of the noodles was dried by wiping with tissue paper.

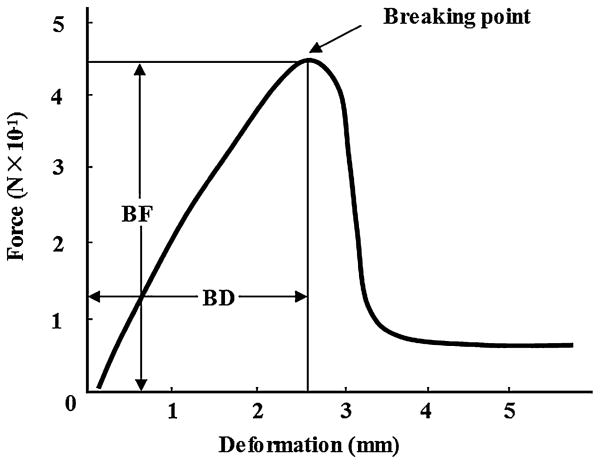

Instrumental texture measurements were performed using a REONER (model RE-33005, YAMADEN Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) fitted with a 2000-g load cell. A cutting test using boiled noodles was performed with a cutting plunger (Type No. 21, YAMADEN Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) at a speed of 5 mm/s. The noodles, cut into 5-cm-long pieces, were placed in the center at right angles to a slot on the sample table (Type No. 102, YAMADEN Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) and crosswise with the stainless steel cutter of a cutting plunger. From the force-deformation curves (Fig. 1), the maximum force (breaking force: BF) and breaking deformation (BD) were determined, and the breaking force/breaking deformation (BF/BD) ratio was calculated. The assay was carried out in triplicate.

Force-deformation curve showing the mechanical properties of noodles. BF: breaking Force, BD: breaking Deformation.

The colors of flour and boiled noodles were evaluated with a chromameter (CM-3500d, Minolta Camera Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) using the Commission International De l’Eclairage (CIE) L* (brightness) a* (red-green) b* (yellow-blue) color system. The measurement of color was carried out in duplicate.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using the software ‘Excel-Toukei 2008’ (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The multiple range test was performed according to Turkey’s method.

Glutenin genotype compositions of the six varieties used in this study are shown in Table 1. Haruyokoi carried Glu-A1b encoding high molecular weight glutenin subunit (HMW-GS) 2* and other varieties carried Glu-A1a encoding 1. Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 carried Glu-B1b encoding 7 + 8, Hokkai 259, Kitanokaori and Haruyokoi carried Glu-B1c encoding 7 + 9 and Haruyutaka carried Glu-B1i encoding 17 + 18. Haruyutaka carried Glu-D1a encoding 2 + 12 and other varieties carried Glu-D1d encoding 5 + 10. Glu-A1a and Glu-A1b on the 1A chromosome, Glu-B1b, Glu-B1c and Glu-B1i on the 1B chromosome and Glu-D1d on the 1D chromosome contribute to strong dough property and good-bread-making properties (Campbell et al. 1987, Cressy et al. 1987, He et al. 2005, Lagudah et al. 1987, Lawrence et al. 1984, Moonen et al. 1982, Payne et al. 1981, Wrigley 2003). Therefore, it was shown that all varieties except for Haruyutaka carried genes contributing to strong dough property on three glutenin loci encoding HMW-GSs.

| Varieties | Glutenin gene (Glu-) | Waxy gene | Flour protein content (%) | Amylose content (%) | Mixograph | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMW-GS | LMW-GS | Wx | Peak time (min) | Peak value (BU) | |||||||||

| A1 | B1 | D1 | A3 | B3 | D3 | A1 | B1 | D1 | |||||

| Yumechikara | a | b | d | f | b | a | a | b | a | 11.2 c | 22.4 ab | 6.72 b | 42.0 b |

| Hokkai 262 | a | b | d | d | g | a | a | b | a | 9.4 e | 23.0 ab | 8.97 a | 36.6 c |

| Hokkai 259 | a | c | d | f | g | a | a | a | a | 12.4 b | 24.6 a | 8.32 a | 38.2 bc |

| Kitanokaori | a | c | d | f | j | c | a | b | a | 10.1 d | 22.5 ab | 5.50 b | 35.9 c |

| Haruyokoi | b | c | d | c | h | a | a | b | a | 12.1 b | 22.4 ab | 5.25 b | 39.5 bc |

| Haruyutaka | a | i | a | c | h | b | a | b | a | 12.3 b | 19.6 b | 4.05 c | 38.3 bc |

| CM | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 11.4 c | 21.6 ab | 5.01 b | 39.7 bc |

| Yumechikara (HM) | a | b | d | f | b | a | a | b | a | 14.1 a | – | 5.05 b | 50.9 a |

| Hokkai 262 (HM) | a | b | d | d | g | a | a | b | a | 11.9 b | – | 9.70 a | 39.1 bc |

Values followed by the same letter in the same column are not significantly different according to the multiple range test of Tukey’s method. CM: commercial flour, HM: heavy manuring culture.

Regarding the LMW-GSs, Yumechikara, Hokkai 259 and Kitanokaori carried Glu-A3f, Hokkai 262 carried Glu-A3d and the two spring wheat varieties carried Glu-A3c at Glu-A3 locus. Gupta et al. (1991) reported that LMW-GS alleles could be ranked with respect to their effects on maximum dough resistance (Rmax), b > d = e > c at Glu-A3 locus and Ito et al. (2011) reported that wheat dough with Glu-A3d was stronger than that with Glu-A3f. Therefore, it was shown that Hokkai 262 carried an allele contributing to strong dough property at Glu-A3 locus. Yumechikara carried Glu-B3b (Liu et al. (2010) reported that Glu-B3ab, Glu-B3ac and Glu-B3ad were could only be identified by the 2-D PAGE method from Glu-B3b, Yumechikara had Glu-B3ab according to the method of classification by Ikeda et al. (2009)), Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259 carried Glu-B3g, Kitanokaori carried Glu-B3j and the two spring wheat varieties carried Glu-B3h at Glu-B3 locus. It has been reported that Glu-B3b and Glu-B3g contribute to strong dough property (Eagles et al. 2002, Funatsuki et al. 2007) and that Glu-B3j produced dough with low Rmax and extensibility value (Eagles et al. 2002). Furthermore, in some previous studies, dough with Glu-B3g was shown to be stronger than that with Glu-B3b (Funatsuki et al. 2007, Ito et al. 2011). Thus, Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259 carried an allele being the most effective for strong dough, followed by Yumechikara at Glu-B3 locus. On the other hand, Kitanokaori carried an allele preventing strong dough. Kitanokaori carried Glu-D3c, Haruyutaka carried Glu-D3b, and the other varieties carried Glu-D3a at Glu-D3 locus. It has been reported that the contribution of Glu-D3 alleles to dough property is less than that on other glutenin loci (Gupta et al. 1994).

These results indicated that Hokkai 262 carried glutenin genes contributing to strong dough at all glutenin loci.

Waxy gene genotype and amylose contentWaxy gene genotypes of the six varieties are shown in Table 1. Hokkai 259 showed DNA markers corresponding to three wild Wx-1 genes (Wx-A1a, Wx-B1a and Wx-D1a). Other varieties showed Wx-A1a, Wx-B1b and Wx-D1a markers (Wx-B1 protein deficiency type).

The amylose content of Hokkai 259 was higher than those of other varieties and commercial flour, presumably due to the wild Wx-1 genotype. Haruyutaka had lower amylose content than those of other varieties and the lower amylose content is thought to due to unknown factors other than the Wx-1 gene.

Flour protein content and dough propertiesThe flour protein content and parameters of dough properties measured by a 2-g mixograph are shown in Table 1. Hokkai 259, Haruyokoi and Haruyutaka had the highest flour protein contents, followed by Yumechikara and commercial flour and Hokkai 262 had the lowest flour protein content. The flour protein contents of Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture were 2 to 3 percent higher than those of the same varieties grown under the condition of standard manuring culture.

Longer PT corresponds to stronger dough, as PT indicates strength of dough. Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259 showed the longest PTs among all varieties. Yumechikara had longer PT than those of Kitanokaori, Haruyokoi and Haruyutaka, though the difference was not significant. Haruyutaka had the shortest PT presumably due to the fact that Haruyutaka does not carry Glu-D1d, which is thought to play the most important role in dough property. Hokkai 262, Hokkai 259 and Yumechikara have glutenin allelic combinations contributing to strong dough property on HMW-GS and LMW-GS loci, e.g., Glu-D1d, Glu-A3d, Glu-B3b and Glu-B3g; however, the contribution of the combination in Yumchikara to the strong dough properties is less than that of combinations in Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259 have.

Relationship between flour properties and texture of boiled pastaThe relationship between flour protein content and breaking force of boiled pasta is shown in Fig. 2. There was no significant correlation between flour protein content and hardness of boiled pasta. Boiled pasta made from Yumechikara, Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259, which have extra strong dough, was harder than that made from other varieties and commercial flour. Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture had the hardest boiled pasta.

Relationship between flour protein content and hardness of boiled pasta. Vertical bars indicate standard errors. CM: commercial flour, HM: heavy manuring culture.

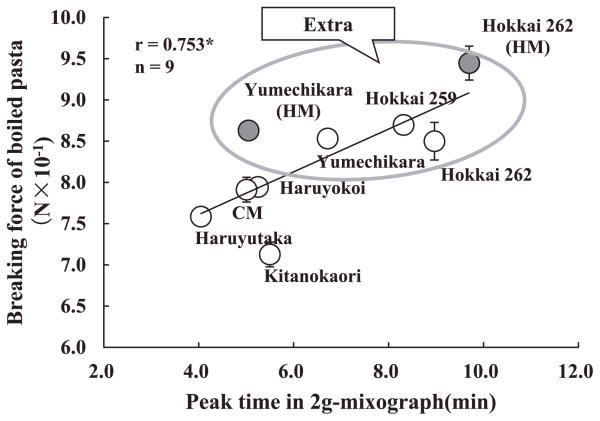

The relationship between PT in a 2-g mixograph and breaking force of boiled pasta is shown in Fig. 3. There was a positive correlation between PT and hardness of boiled pasta, indicating that the hardness of boiled pasta was affected by dough strength. Although Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of standard manuring culture had the lowest flour protein content, the hardness of the boiled pasta was equal to those of Yumechikara and Hokkai 259. It is thought that the glutenin allelic composition of Hokkai 262 increased the hardness of boiled pasta of common wheat in nature. Since only Hokkai 262 possessed all of the alleles Glu-D1d, Glu-A3d and Glu-B3g, the combination of three alleles may be crucial for the hardness of boiled pasta.

Relationship between peak time in a 2 g-mixograph and hardness of boiled pasta. Vertical bars indicate standard errors. CM: commercial flour, HM: heavy manuring culture.

In durum wheat, it is thought that the combination of Glu-A3 and Glu-B3 alleles is crucial for dough strength. LMW-2 type was related to good pasta quality. LMW-2 type durum varieties show five alleles at the Glu-A3 locus and four at Glu-B3. Glu-A3c, Glu-A3d, Glu-A3f and Glu-B3g are included among these alleles; however, Glu-B3h, Glu-B3b and Glu-B3j are not (Nieto-Taladriz et al. 1997). It is therefore thought that Glu-B3g may greatly contribute to good texture of boiled pasta made from durum wheat and Hokkai 262.

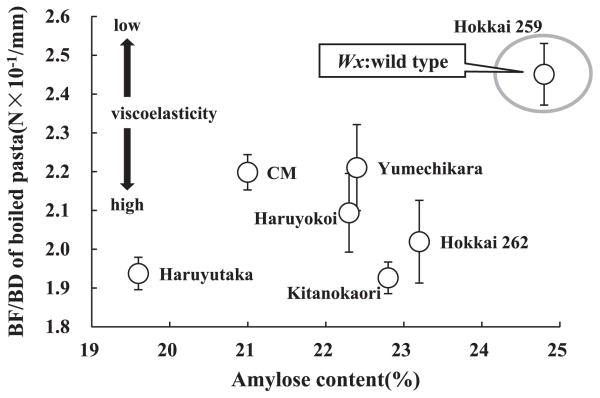

Relationship between amylose content and viscoelasticity of boiled pastaThe relationship between amylose content and BF/BD of boiled pasta is shown in Fig. 4. Hokkai 259 carrying wild-type waxy genes had the highest amylose content and the highest BF/BD, indicating that boiled pasta made from Hokkai 259 had the lowest viscoelasticity. The other varieties and commercial flour lacking Wx-B1 protein had lower amylose content and lower BF/BD than those of Hokkai 259. Boiled pasta made from these varieties had high viscoelasticity. The texture of boiled pasta made from Hokkai 259 was most similar to that made from durum wheat, which has a normal range of amylose contents.

Relationship between amylose content and viscoelasticity of boiled pasta. Vertical bars indicate standard errors. CM: commercial flour.

The colors of flour paste and boiled pasta are shown in Table 2. For flour paste, the brightness (L* value) of Hokkai 262 was the highest, followed by Yumechikara, and Haruyutaka had the lowest L*. The degree of red (a* value) was lowest for Hokkai 262 and highest for Haruyutaka. The degree of yellow (b* value) was highest for Kitanokaori and lowest for Haruyutaka. Flour paste brightness values of Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture were lower than those of the same varieties grown under the condition of standard manuring culture. Similarly, flour redness values of Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture were higher than those of the same varieties grown under the condition of standard manuring culture. The flour of these varieties was discolored by increase of protein content under the condition of heavy manuring culture.

| Varieties | Flour color | Noodle color | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L* | a* | b* | L* | a* | b* | |

| Yumechikara | 88.5 b | 0.77 cd | 14.0 c | 76.6 a | 2.45 cd | 30.1 c |

| Hokkai 262 | 88.8 a | 0.53 f | 13.8 d | 76.7 a | 2.46 cd | 32.3 b |

| Hokkai 259 | 87.3 e | 0.92 b | 13.7 d | 71.7 f | 2.70 bc | 25.0 e |

| Kitanokaori | 87.9 d | 0.81 bc | 18.4 a | 75.8 bc | 2.96 a | 34.4 a |

| Haruyokoi | 87.1 f | 0.82 bc | 13.1 e | 75.2 c | 2.88 ab | 29.3 c |

| Haruyutaka | 86.4 g | 1.01 a | 12.7 f | 74.0 d | 2.91 ab | 30.3 c |

| CM | 87.8 d | 0.64 e | 16.3 b | 76.4 ab | 3.02 a | 32.6 b |

| Yumechikara (HM) | 87.1 f | 0.65 e | 14.0 c | 72.8 e | 2.31 d | 25.8 de |

| Hokkai 262 (HM) | 88.2 c | 0.67 de | 13.6 d | 75.4 c | 3.06 a | 27.2 d |

Values followed by the same letter in the same column are not significantly different according to the multiple range test of Tukey’s method. CM: commercial flour, HM: heavy manuring culture.

For boiled pasta, the brightness of Hokkai 262 and Yumechikara was highest, followed by commercial flour and Kitanokaori, and Hokkai 259 had the lowest L*. The degree of redness was lowest for Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 and highest for Kitanokaori and commercial flour. The degree of yellowness was highest for Kitanokaori and lowest for Hokkai 259. The results indicated that the colors of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of standard manuring culture were superior to those of boiled pasta made from other varieties. However, the L* value of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture was inferior to the values of boiled pasta made from other varieties except for Hokkai 259.

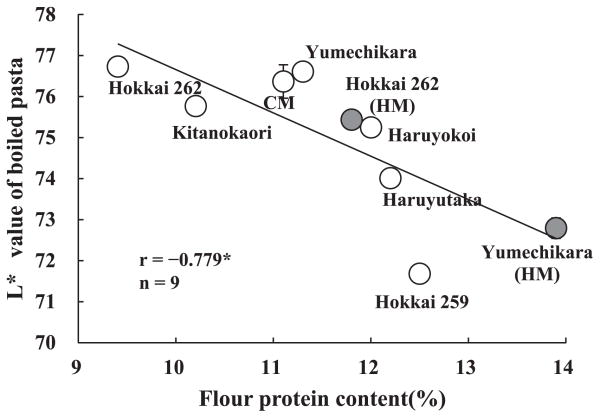

The relationship between flour protein content and L* value of boiled pasta is shown in Fig. 5. There was a negative correlation between flour protein content and brightness of boiled pasta. This result suggests that discoloration of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture (3.8% reduction in L* compared to that of the standard condition) was caused by increase of flour protein content. On the other hand, discoloration of boiled pasta made from Hokkai 262 grown under the condition of heavy manuring culture was less than that of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara (1.3% reduction in L* compared to that of the standard condition).

Relationship between flour protein content and brightness of boiled pasta. Vertical bars indicate standard errors. CM: commercial flour, HM: heavy manuring culture.

Many previous studies showed that the discoloration of raw noodles such as yellow alkaline noodles during storage was influenced by polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activities in wheat flour (Baik et al. 1994, 1995, Kruger et al. 1992, 1994a, 1994b). Accordingly, we attempted to clarify the difference of flour PPO activity between flours of Hokkai 262 and those of Yumechikara grown under the same manuring conditions as this study (standard and heavy manuring culture) in 2010–2011. PPO activities were evaluated by the L* value of a simple method (Ito et al. 2008). Hokkai 262 had a higher L* value (standard manuring: 45.2a, heavy manuring: 44.9a) than that of Yumechikara (standard manuring: 39.4c, heavy manuring: 43.6b, Values followed by the different letter are significantly different according to the multiple range test of Tukey’s method). Therefore, this result showed that Hokkai 262 had lower PPO activity in flour and it is expected that discoloration of raw pasta noodle made from Hokkai 262 is less than that of raw pasta noodle made from Yumechikara.

Evaluation of fresh pasta-making propertiesFresh pasta made from Yumechikara, Hokkai 262 and Hokkai 259 carrying glutenin alleles contributing to strong dough property was harder than that made from other varieties. Furthermore, fresh pasta made from Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 had high viscoelasticity resulting from a lack of Wx-B1 protein and low amylose content. Therefore, these two varieties had good fresh pasta-making properties for preferable texture. Hokkai 262 carries a glutenin allelic composition contributing to the strongest dough property among the varieties used in this study and it has good fresh pasta-making properties for hardness.

Moreover, the noodle color of fresh pasta made from Yumechikara and Hokkai 262 is superior to that of fresh pasta made from other varieties. However, the brightness of boiled pasta made from Yumechikara declined remarkably when its flour protein content increased with heavy manuring culture. On the other hand, boiled pasta made from Hokkai 262 had higher brightness in color under both standard and heavy manuring conditions. Therefore, the results suggested that pasta made from Hokkai 262 has a better color than that of pasta made from Yumechikara.

Hokkai 259 had a different texture from other varieties. Boiled pasta made from Hokkai 259 had low viscoelasticity because of the presence of wild-type alleles on three Wx loci and higher amylose content. Therefore, the results suggested that consumers can taste pasta noodles having characteristic texure (noodles can be easily bitten off without being sticky) made from Hokkai 259.

To sum up the results, pasta made from extra strong wheat varieties has good hardness and Hokkai 262 has extraordinary fresh pasta-making properties. Consumers can choose between two types of noodle, noodles having high viscoelasticity and noodles being easily bitten off, as the occasion demands.