2023 年 7 巻 2 号 p. 1-11

2023 年 7 巻 2 号 p. 1-11

Objective

Japan is experiencing an influx of foreign healthcare workers, who are members of racial and/or ethnic minority groups and are likely to face ethical challenges. To help address these challenges, we developed a measurement scale to assess the psychosocial work environment of nurses and examined its reliability and validity.

Method

We developed a preliminary measurement scale comprising 40 questions based on discussions with researchers, nursing managers, and published literature. The questions focused on social capital, ethical climate (including social exclusion), and ethical leadership. A three-round Delphi panel survey was conducted with nursing department directors (N = 302) to reach consensus on the items to be included in the new scale, which was tested in a cross-sectional survey of all staff nurses (N = 1,114). First, an exploratory factor analysis was conducted, and examined the construct validity from the results of the factor structure. Next, based on results of the factor analysis, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to confirm reliability. The validity was further examined and confirmed using the K6 scale confirmed the validity, a screening measure of psychological distress. Desirability of the nursing practice environment was measured using the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index.

Result

The nursing department directors agreed on 78% of the original 40 items. Factor analysis revealed three factors, namely “social capital in the workplace,” “ethical leadership,” and “exclusive workplace climate,” with high internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha: .87 – .95). Construct validity was established via high factor loadings for each item. Pearson’s correlations and t-tests confirmed criterion-related and construct validity between each variable.

Conclusion

We confirmed the reliability and validity of the Social Capital and Ethical Climate of the Workplace scale. The scale could be a useful tool to help nurse managers and hospital employers maintain a healthy work environment for both native and racial and/or ethnic minority health care providers who face ethical challenges at their workplace.

The global population is rapidly aging (United Nations, 2019). In Japan, which has the largest aging population globally, the government has established new systems since 2008 to accept foreign care workers (FCWs) to meet the increased demand for health and welfare workers (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2019). This suggests that nurses’ workplaces in Japan are becoming more multicultural.

Globally, nurses are impacted by ethical challenges in their working environment. Healthcare workers in European countries were exposed to adverse social behavior, including physical and verbal violence and intimidation (Eurofound, 2012). In Japan, the healthcare and welfare industry was ranked the highest concerning the number of workers’ compensation cases reported due to mental illness caused by ethical challenges such as harassment from supervisors in the work environment (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2022). Furthermore, healthcare providers from racial and/or ethnic minority groups are more likely to face workplace bullying (Lu et al., 2022), and migrant healthcare workers may face discrimination and inequalities in treatment from residents, managers, or colleagues (Dahle & Seeberg, 2013). Since the ethical climate plays a vital role in influencing registered nurses’ professional turnover intentions (Hart, 2005), the work challenges may escalate the human resource issues of nurses, including foreign nurses who will work at hospitals in Japan.

To address the above-mentioned issues, a measurement scale to evaluate the extent to which the psychosocial work environment is supportive and ethical for nurses, both in Japan and abroad, would be useful. In this context, “social capital” is a beneficial concept. Read (2014) defines nurses’ workplace social capital as shared assets and ways of being and knowing that are evident in and available through nurses’ networks of social relationships at work”. Social capital in the hospital workplace is associated with depressive symptoms (Jung et al., 2012), emotional exhaustion among hospital nurses (Kowalski et al., 2010), and poor-quality patient care and job satisfaction among nurses (Shin & Lee, 2016).

However, the mechanisms of social capital might have other undesirable consequences, such as feelings of exclusion (Hofmeyer & Marck, 2008). Workplace exclusion is directly associated with employees’ intentions to quit (Zheng et al., 2016). Given the current circumstances in nurses’ work environment in Japan, wherein there has been an increasing influx of FCWs (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2019), who are healthcare providers from racial and/or ethnic minority groups and more likely to face ethical challenges (Lu et al., 2022; Dahle & Seeberg, 2013), we proposed that social capital should be included in measurement scales that assess the supportive and ethical aspects of work environment considering the limitation of the mechanisms of social capital.

While social capital includes elements of trust (Kawachi, 1999; Read, 2014), trust is also associated with ethical leadership and the degree to which leaders display fair and moral behavior (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008). In contrast, Kalshoven et al. (2011) argue that although perceived ethical leadership is positively associated with trust, trust and ethical leadership are different constructs.

Although previous studies have measured social capital in nurses’ work environments (Middleton et al., 2018; Shin & Lee, 2016), they did not consider the elements of social capital, ethical climate, and ethical leadership in combination. Here, we developed a new multidimensional assessment scale, the Social Capital and Ethical Climate at the Workplace (SEW), that combines these elements to evaluate the psychosocial work environment of hospital nurses and examined its reliability and validity. The new scale would help nurse managers and hospital employers enhance occupational health in Japanese hospitals’ work environment, which is becoming more multicultural for both native and healthcare providers from racial and/or ethnic minority groups who face ethical challenges.

Two quantitative studies were conducted: a three-round Delphi panel survey to determine the scale questions and a cross-sectional survey to test the reliability and validity of the SEW.

2. Setting and SampleThe participants included individual nurses (staff nurses) and hospital organizations (nursing department directors). First, to reach consensus among the latter regarding the 40 question items, we conducted a three-round Delphi panel survey with nursing department directors. Through questionnaires, the Delphi technique aggregates the views and judgments of all participants to identify mutual positions and establish priorities (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004).

To examine the reliability and validity of the SEW, which used the original questionnaire items selected through the three-round panel survey, we designed a cross-sectional survey with convenience sampling. Staff nurses from 11 hospitals in a Japanese prefecture acted as participants. All individuals consented to participate.

3. Data CollectionThe three-round Delphi panel survey was conducted in 2015. Anonymous self-administered questionnaires were distributed to all hospitals’ nursing department directors (or an equivalent position) (N = 302) in a specific prefecture in western Japan. In the first round, participants completed and returned the questionnaire. In the second and third rounds, we sent a summary of the previous round results. Participants confirmed that the summary was accurate and provided their opinions via questionnaire. The response rates from the first-panel survey to the third-panel survey were 26% (n = 78), 25% (n = 77), and 25% (n = 74), respectively.

Next, we conducted a cross-sectional survey from September to November 2015 to assess the SEW’s reliability and validity. Anonymous self-administered questionnaires were distributed to all staff nurses (N = 1114) through administrators of 11 hospitals (66 wards), which accepted to cooperate this survey in the specific prefecture in western Japan. The participants completed and returned the questionnaire to a researcher by postal mail (response rate = 83%). We analyzed only completed questionnaires (n = 779; valid response rate = 74%).

4. Questionnaire for the Three-round Delphi Panel SurveyThe anonymous self-administered questionnaire collected demographic data and included 40 question items of the SEW on social capital, ethical climate including social exclusion, and ethical leadership (Hofmeyer, 2003; Read, 2014), which were developed after several discussions with researchers and nursing managers.

Of those, 26 items assessed favorable conditions for a supportive work environment on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 7 (very important). Higher scores represented greater importance for fostering a supportive work environment. The remaining 14 items addressed unfavorable conditions of an ethical work environment that were evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not problematic at all) to 7 (very problematic). Higher scores represented more problematic conditions from an ethical standpoint.

5. Questionnaire for the Cross-sectional SurveyThe anonymous self-administered questionnaire included demographic data and the items of the SEW, which were chosen based on the results of the Delphi panel survey. In addition, to assess the SEW’s validity, we used the K6 scale (Kessler et al., 2003; Furukawa et al., 2003;2008), an epidemiologic screening measure of psychological distress. K6 has demonstrated validity for major depressive disorder and other mental disorders and high internal consistency. The Japanese version of K6 demonstrated screening performances equivalent to the original English version regarding validity, and the scales are widely available on government websites. The participants were asked about any recently experienced symptoms or behaviors related to depression or anxiety. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 4 = all of the time to 0 = never. Therefore, the unweighted summary scale has a 0–24-point range. Based on total scores, the participants were dichotomized into a high- (≥ 5) and low-risk group (< 5) for depression and anxiety (Kessler et al., 2003; Furukawa et al.`, 2003;2008).

To further assess the SEW’s validity, we used the Japanese version of the Practice Environment Scale of the Nursing Work Index (PES-NWI) after obtaining the creator’s permission. The PES-NWI measures the hospital practice nursing environment (Lake, 2002) and comprised 31 items with five subscales: “nurse participation in hospital affairs,” “nursing foundations for quality of care,” “nurse managers’ ability, leadership, and support of nurses,” “staffing and resource adequacy,” and “collegial nurse-physician relations” (Lake, 2002; Ogata et al., 2008). It has demonstrated internal consistency and content validity with high reliability for nurses (Lake, 2002). The items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The average score on each subscale was calculated. Higher scores indicated higher desirability.

6. Sample SizeThe sample size was calculated for the primary analysis that examined criterion-related validity using G*Power 3.1.9.2 (Faul et al., 2009). Assuming an alpha level of .05 and 95% power when a t-test was used for differences between two independent means (two groups), the required sample sizes for effect sizes 0.30 and 0.25 were 580 and 834, respectively.

7. Data AnalysisFirst, descriptive statistics were calculated for the data gathered from the three-round Delphi panel survey. As a ranking process in the Delphi survey (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004), we calculated mean scores and standard deviations (SD). We then calculated the consensus ratio (the percentage of responses with scores of 6 or 7) and ranked the items by consensus ratio. Each item was regarded as being agreed upon by the participants if the item attained a set consensus ratio of ≥ 75.1% and mean score ≥ 6.1. Moreover, we confirmed the participants’ opinions via the second- and third-round panel surveys to refine the items.

Next, based on the results from the three-round Delphi panel survey, items for the SEW were carefully selected for the cross-sectional survey. We checked each item for the ceiling (mean +1 SD > 7) and floor effects (mean –1 SD < 1) and assessed the participants’ opinions written in the questionnaires.

Regarding the cross-sectional survey, we calculated descriptive statistics using complete data after excluding missing data. Exploratory factor analysis using Principal factor methods with oblimin rotation was performed on selected questionnaire items to assess construct validity. Data of the results (the value of KMO and Bartlett's Test, eigenvalue, variance explained, factor loading) were confirmed.

We calculated the mean scores for three SEW subscales based on the factor analysis results to assess the SEW’s internal consistency and reliability. We calculated Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, corrected item-total correlation. Additionally, we confirmed whether there was subscale for which Cronbach’s alpha increased if an item was deleted.

Furthermore, to assess criterion-related validity, we calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients between subscales of the SEW and that of the PES-NWI and K6 scales. We also conducted t-tests to compare scores of each sub-scale of the SEW between the high-risk (K6 score ≥ 5) and low-risk (K6 score < 5) groups. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 25.0 (IBM Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A p-value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

8. Ethical ConsiderationThe panel survey was approved by Kyoto Tachibana University Ethics Screening Committee in 2013 (#13-13), and the cross-sectional study was approved by the ethics review board of Tokyo Gakugei University in 2015 (#247). Participation was voluntary with freedom to withdraw at any time. Participants were assured of confidentiality.

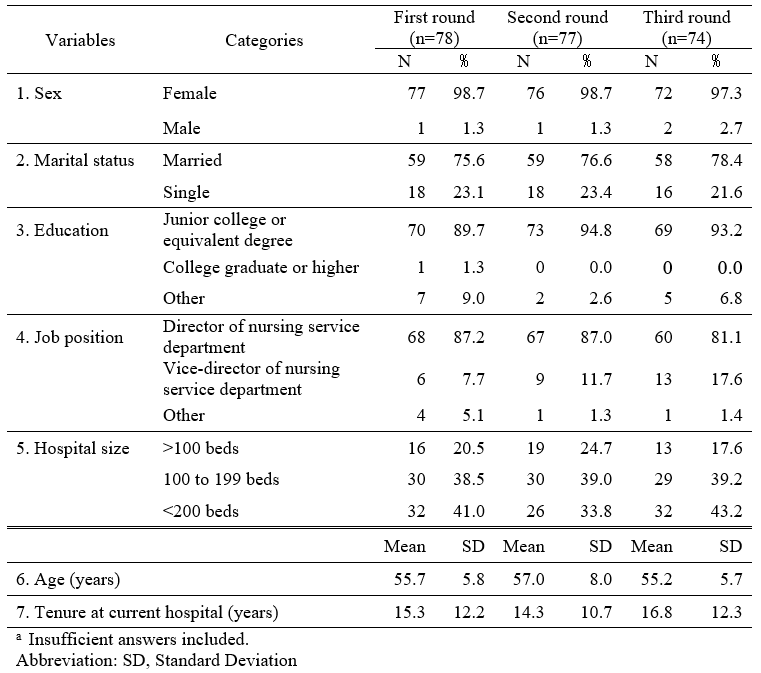

The participants’ characteristics in the three-round Delphi panel survey for hospital organizations (nursing department directors) did not vary substantially over rounds (Table 1). More than 80% of the participants in the panel surveys were in their fifties, with an average of 8 years in their current position.

Table 1. Basic attributes and characteristics a

Based on the three-round Delphi panel survey results, we excluded nine out of the original 40 items, which were regarded as not in agreement among participants since they did not reach a consensus level: calculated percentage ≥75.1%, mean score ≥ 6.1. The remaining 31 items were included in the SEW for the cross-sectional survey as they reached a level of consensus after the third round.

In the results of descriptive statistics in the cross-sectional study for staff nurses, 93% (n = 724) of all participants (n = 779) were female. The mean age was 37.42 years, and the mean tenure of employment at the current hospital was 6.57 years. Most reported having a junior college degree or vocational school equivalency (n = 669; 85.9%). In addition, most reported working for general private hospitals (n = 486; 62.4%), whereas the size of the hospitals varied.

After excluding missing data, we calculated descriptive statistics for the 31 remaining SEW items using completed data. We excluded seven items with a ceiling or floor effect (Problems arising in the workplace are resolved early and effectively) and two word-deficient items. Subsequently, we conducted a factor analysis and excluded the two items identified as double loadings items (≥ .30).

Then, we conducted a final factor analysis with the remaining 20 items. Three factors- “social capital in the workplace,” “ethical leadership,” and “exclusive workplace climate” explained 67.9% of the variance. They all showed high internal reliability (Cronbach’s alphas: .87 – .95) (Table 2). We calculated the mean score for the three SEW subscales. Greater mean scores on the two subscales (“social capital in the workplace; the mean score for nine items” and “ethical leadership; the mean score for five items”) denoted greater perceived favorable characteristics; larger score on the subscale of exclusive workplace climate subscale (mean score for six items) denoted greater perceived unfavorable work environment characteristics.

Table 2. Factor analysis of Social Capital and Ethical Climate in the Workplace scale (SEW) (n=779)a

Although not shown in the table, the corrected item-total correlations were .60 –.79 for “social capital in the workplace,” .64 –.77 for “ethical leadership,” and .71 –.84 for “exclusive workplace climate” (data not shown). Additionally, there was no subscale where Cronbach’s alpha increased when an item was deleted.

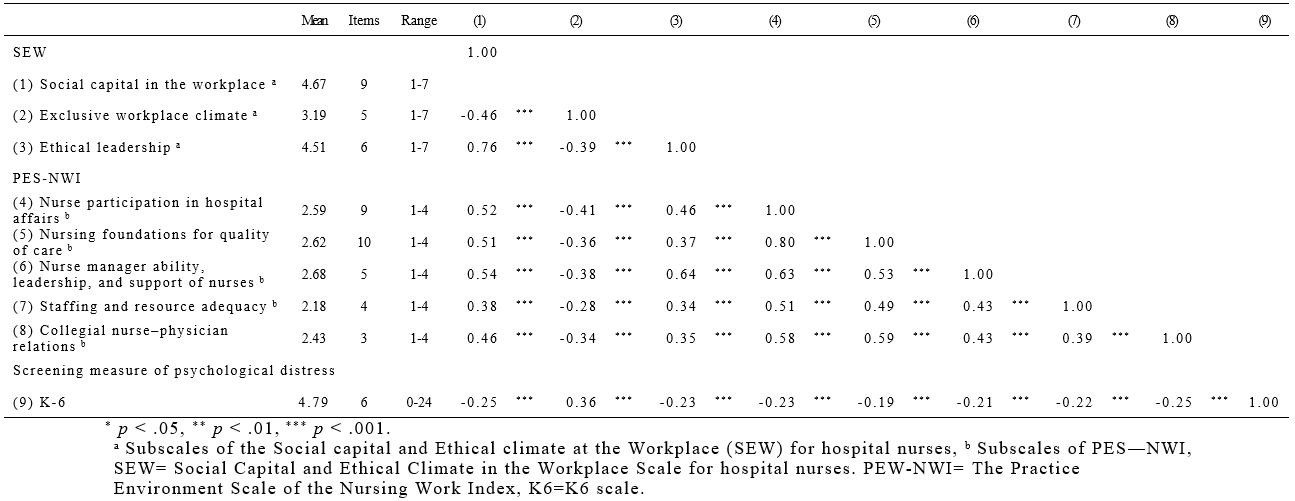

As shown in Table 3, the three subscales were moderately correlated (r = .39 –.76, p < .001). Similarly, correlations between the subscales of the SEW and the PES-NWI were moderately strong (p < .001), confirming criterion-related validity. “Ethical leadership” of the SEW and “nurse managers’ ability, leadership, and support of nurses” of the PES-NWI had the strongest positive correlation (r = .64, p < .001).

Table 3. Pearson’s correlations between the SEW, PES-NWI, and K6

The mean scores of the three subscales of the SEW differed significantly between the high- and low-risk groups of psychological distress (p < .001). The high-risk group perceived less “social capital in the workplace” and “ethical leadership,” and perceived greater “exclusive workplace climate” (Table 4).

Table 4. T-tests for each Subscale of the SEW between Two Psychological Health-Status Groups (n=779) a.

We developed a new multidimensional assessment scale for evaluating the extent to which the psychosocial work environment is supportive and ethical for hospital nurses. The SEW included items representing three elements- social capital, ethical climate including social exclusion, and ethical leadership. High factor loadings of the final 20 items into one of three factors provided evidence of construct validity. In addition to high internal consistency evidenced by the Cronbach’s alpha values, validity of the SEW was established using two external measurement tools.

The factor analysis of the SEW reflected the a priori elements of social capital, ethical climate including social exclusion, and ethical leadership, explaining 67.9% of the total variance, exceeding the minimum acceptable target of 60% for scale development. Moreover, we could not identify any subscales where deletion of an item resulted in a higher Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach’s alpha values of the three subscales of SEW (.87–.95) showed high internal consistency. These values were satisfactory for use of the scale as a research tool (Tavakol & Dennick, 2011).

Regarding construct validity, measurements may not include all dimensions and thus be too narrow, or measurements may include dimensions that are related to distinct constructs and may thus be too broad (Messick,1995). In our factor analysis, the three-factor structure confirmed construct validity, while criterion-related validity was established by strong correlation coefficients between the SEW and the PES-NWI and K6 scales.

Two sub-scales of the SEW, for which higher scores denoted more favorable characteristics (social capital in the workplace and ethical leadership), were positively correlated with all the subscales of the PES-NWI, which is widely used to assesses characteristics of nurses’ favored practice environment (Lake, 2002). The remaining subscale of the SEW (exclusive workplace climate), for which higher scores denoted more unfavorable characteristics, was negatively correlated with the PES-NWI subscales, and vice versa for the K6. These findings support the SEW’s concurrent and criterion-related validity. However, since the correlation regarding “exclusive workplace climate” was relatively weak (r = .28 – .41), further studies should examine its validity.

The strongest correlation was between the SEW’s “ethical leadership” and “social capital in the workplace” (r = .76) sub-scales, followed by that between the SEW’s “ethical leadership” and PES-NWI’s “nurse managers’ ability, leadership, and support of nurses” (r = .66) sub-scales. These findings suggest that nurse leaders in hospitals can contribute to strengthening social capital and enhancing relationships between nurses. Meanwhile, the relatively strong correlation coefficients suggest that ethical leadership is associated with trust (De Hoogh & Den Hartog, 2008).

In terms of criterion validity, participants in the high-risk group for depression (K6 score > 5) had low levels of perceived social capital and experienced greater social exclusion, consistent with previous findings (Jung et al., 2012). Previous studies have also found that nurses with the lowest levels of perceived workplace social capital showed elevated mental distress and poorer self-rated health (Middleton et al., 2018). Moreover, our findings provide new insights into undesirable conditions caused by extreme social capital deficits at work (Hofmeyer & Marck, 2008), which may cause psychological adverse effects (Williams & Nida, 2009) and influence their intentions to quit (Zheng et al., 2016).

Taken together, we show that the three-factor SEW may be a useful, multidimensional tool for assessing supportive and ethical work environments for hospital nurses. Currently, hospitals in Japan are required to prevent harassment (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2022) and discrimination against migrant healthcare workers (Lu et al., 2022; Dahle & Seeberg, 2013). The SEW could assess the conditions of nurses' work environment and help facilitate intervention to address these issues.

Our findings may be limited by the low response rate for the three-round panel survey, and the items may not represent the views of all organizations. However, Delphi groups do not rely on size to obtain statistical power, but rather on group dynamics to arrive at consensus among experts (Okoli & Pawlowski, 2004). Therefore, our findings may be sufficient considering that the response ratio was approximately the same for all panel rounds, and homogeneity and consensus were achieved on all items. Additionally, participants in the three-round panel and cross-sectional surveys were nursing department directors or staff nurses recruited through convenience sampling. Thus, the results might have been influenced by sampling bias. Lastly, since this study was conducted before the coronavirus disease pandemic, it does not consider changes in the healthcare environment since then. In light of these changes, large, longitudinal studies are required to examine further the SEW’s reliability, validity, and generalizability to promote its future utilization.

We developed a new scale, the SEW, which exhibited high internal consistency and criterion-related and construct validity. The SEW may be a useful tool to help nurse managers and hospital employers encourage a healthy work environment for native nurses and ethnic minority healthcare providers who face ethical challenges in their workplace (Lu et al., 2022; Dahle & Seeberg, 2013).

No conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP25463657 and JP16H05612. The authors deeply appreciate the cooperation of all respondents from the hospitals.

MT, principal author, contributed to the study concept and design, data collection, statistical analyses and interpretation, and drafting and final revision of the manuscript. MN contributed to the study design, drafting, and final manuscript revision. All authors met the authorship criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.