2023 Volume 64 Issue 9 Pages 2070-2076

2023 Volume 64 Issue 9 Pages 2070-2076

We have investigated the hydrogen-annealing influence on the crystalline and electronic structures, and magnetic properties of La2/3Ca1/3MnO3 (LCMO). The results have indicated that the annealing at 700 and 900°C (labeled as LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, respectively) readily reduced single-phase LCMO, resulting in a complex phase composition of several isostructural oxygen-deficient perovskite-type phases coexisting with the Ruddlesden-Popper (La/Ca)2MnO4-type phase. While a Mn3+/Mn4+ mixed valence is present in LCMO, the hydrogen-annealed samples mainly have Mn2+ and Mn3+ ions. Under such circumstance, large changes in magnetic parameters have been recorded, such as remarkable decreases in values of the magnetization, the Curie temperature (from 251 K for the as-prepared LCMO through 240 K for LCMO-700 to ∼221 K for LCMO-900), and the magnetic-entropy change. Particularly, the crystal and electronic-structure changes also enhance the magnetic inhomogeneity, resulting in a strong development of the Griffiths phase, and cause the first-to-second-order phase transformation. These results reflect the instability of the LCMO perovskite-type manganite versus hydrogenation.

Fig. 3 K-edge XAS spectra of the fabricated samples compared with those of manganese oxides as references. The arrow shows the absorption-edge (Abs. edge) shift of Mn.

Holed-doped perovskite-type manganites are known as materials with the general formula of Ln1−xMexMnO3, where Ln and Me are usually trivalent rare-earth and divalent-alkali elements, respectively. This material system was firstly investigated by Jonker and Santenin 1950.1) They found a Mn3+/Mn4+ mixed valence and a unusual correlation between electrical conduction and ferromagnetism. In 1951, Zener2) proposed the double-exchange model to explain this unusual correlation. Investigating a series of LnxCa1−xMnO3 compounds, it was discovered a coexistence of ferromagnetic (FM) and anti-FM (AFM) interactions, which were strongly dependent on the concentration ratio of Mn3+/Mn4+, the Mn–O bond distance and the Mn–O–Mn bond angle.3,4) Thus, the double-exchange model was further developed to clarify experimental results.5–8) After these pioneering works, many investigations were carried out that provided much background knowledge about perovskite-type manganites.9–13)

An important milestone in studying Ln1−xMexMnO3 materials is the discovery of the colossal magnetoresistance (CMR) effect (a sharp drop of the electrical resistancejust below the Curie temperature (TC) in the presence of a magnetic field) in 1994 and 1995.14–16) Stimulated by this discovery, more and more theoretical and experimental works were deployed that incessantly enriched the electronic and magnetic phase diagrams of Ln1−xMexMnO3, as shown in review papers.17–19) Millis et al.20,21) suggested a rapid decrease in resistivity to the interplay between the electron-phonon coupling arising from the Jahn-Teller effect and double-exchange mechanism. This suggestion was confirmed upon the studies associated with Raman scattering, neutron diffraction, electron spin resonance, and thermoelectric power.22–24) In an attempt to explain transport and magnetotransport behaviors more reasonably, the two-orbital model,19) phase separation,25) percolative phase separation,4) and Griffiths phase/singularity26) were also proposed. Due to complex couplings among the spin, charge, orbital, and lattice degrees of freedom, apart from the CMR effect, metal-insulator transition and Jahn-Teller distortions, it has also been discovered other intriguing properties, such as the charge/orbital/spin-ordering, electronic-phase separation, finite size effects, grain boundary related effects, magnetic frustration, and so forth.19,27,28)

Among Ln1−xMexMnO3 compounds, La2/3Ca1/3MnO3 (LCMO) has been attracted much more interest because it shows the largest CMR and magnetocaloric (MC) effects near room temperature, Griffiths phase/singularity, and intrinsic first-order phase transition around its ferromagnetic-paramagnetic (FM-PM) transition temperature (TC).29–32) It can be tuned the first-order character of LCMO to the tricriticality (the crossover of the first-order to second-order transition)33) or a second-order character upon the doping into the La/Ca and Mn sites,29,34–36) reducing dimensionality,30,37–39) or applying high magnetic fields.31) Particularly, as studying LCMO materials with oxygen deficiency, it has been found the reduced carrier density and FM order,40,41) and structural phase separation,42) which are ascribed to an increase concentration of Mn4+,40) or Mn3+.41,43) To gain more knowledge about LCMO materials with large oxygen deficiency, we have prepared LCMO samples annealed in hydrogen ambient, and studied their crystalline/electronic structures and magnetic properties. The magnetic-phase-transition character and the magnetic-entropy change around TC have also been taken into account.

Firstly, a polycrystalline sample LCMO was prepared by the solid-state reaction route in air at 1300°C for 24 h. High-purity chemicals of La2O3, CaCO3 and MnO2 (99.9%, Sigma-Aldrich) were used as initial materials. Detailed descriptions of the fabrication were shown in some previous works.31,37) After synthesizing a single-phase LCMO sample, it was divided into two pieces. These pieces were then in sequence annealed in a mixture gas of 90% Ar + 10% H2 (denoted as a hydrogen ambient) at 700 and 900°C for 1 h. The crystalline structure of the final samples were checked by a Bruker X-ray diffractometer (D8 Discover), and Si powder was mixed and used for calibration. Recorded X-ray diffraction patterns were analyzed by the Rietveld technique. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) located at the 8C beamline of the Pohang Accelerator Laboratory (South Korea) was used to analyze the valence change of Mn. Temperature and magnetic-field dependences of the magnetization, M(T, H), were studied by using a superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer.

Firstly, the structural characterizations of the as-prepared and hydrogen-annealed LCMO samples have been studied by means of the X-ray diffraction (XRD), using as-prepared LCMO as reference. For the as-prepared LCMO, as seen in Fig. 1(a), the Rietveld refinement has revealed that the sample is single phase adopting the Pnma orthorhombic perovskite-type structure (as illustrated in Fig. 2(a), labeled as P1 phase) with the lattice parameters a = 5.4872(3), b = 7.7396(7), c = 5.4730(3) Å, and V = 232.43(3) Å3. The refined lattice parameters are similar to those previously reported on stoichiometric La0.7Ca0.3MnO3, evidencing a low oxygen deficiency in the as-prepared sample.23) Furthermore, the XRD pattern of LCMO-700 demonstrates a significant change compared to that of LCMO, indicating a phase transformation. It can be seen from Fig. 1(b), besides the diffraction peaks of the Pnma orthorhombic structure of LCMO, the appearance of extra peaks located at 2θ positions of 23.8, 27.7, 31.2, 43.2, 55.3, and 57.2° as well as a strong enhancement in peak intensity at the 2θ positions 42.1 and 64.7° were detected. Data analysis has shown that these changes corresponding to the formation of the tetragonal I4/mmm Ruddlesden–Popper phase of (La/Ca)2MnO4 (named as P2) having lattice parameters a = b = 3.8905(3) Å, and c = 12.849(2) Å. The crystal structure of the P2 phase is demonstrated in Fig. 2(b). The Rietveld refinement within the combination of the P1 and P2 phases provided a satisfactory fit to the experimental data with good quantity factors Rp = 4.57%, Rwp = 6.18% and Rexp = 6.52%. The weight fraction of these phases was estimated at about 41.4% and 58.6% for the P1 and P2 phases, respectively. Similarly, the formation of the P2 phase was observed upon the reduction of La0.8K0.2MnO3 in the 10% H2 + 90% N2 atmosphere.44)

XRD patterns of as-prepared LCMO (a) and hydrogen-annealed LCMO-700 (b) and LCMO-900 (c) samples and refined by the Rietveld method. Experimental points (blue symbols) and refined curves (red lines) are shown. The inset of (c) shows an enlarged region of the XRD pattern of LCMO-900, demonstrating the coexistence of perovskite-type phases with different oxygen concentrations (La/Ca)MnO3−α and (La/Ca)MnO3−β (α < β).

Crystal structure of (La/Ca)MnO3-type (a) and (La/Ca)2MnO4-type (b) phases.

In the XRD pattern of the LCMO-900 sample, it was clearly observed a dramatic decrease in the relative intensity of diffraction peaks of the P2 phase, indicating the phase reduction. Moreover, a close examination reveals a broadening of the diffraction peaks of the P1 phase as shown in the inset of Fig. 1(c). Data analysis showed that the observation is associated with the formation of a new structural phase, named as P3, having the same perovskite structure as the P1 phase with lattice parameters a = 5.587(3) Å, b = 7.793(2) Å, c = 5.548(2) Å, and V = 241.6(2) Å3 fairly larger compared to the P1 phase. The Rietveld refinement involving a combination of P1, P2 and P3 phases provided a satisfactory fitting quality Rp = 3.88%, Rwp = 6.23%, and Rexp = 6.55%. The weight fractions are about 54.8%, 10.8% and 34.4% for the P1, P2, and P3 phases, respectively.

As a result of the structural refinement, it has been established the P3 phase demonstrates an expansion in the unit cell upon increasing annealing temperature from V = 232.43(3) Å3 for LCMO to V = 233.03(4) and 234.43(8) Å3 for LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, respectively. This observation can be explained by an increase in oxygen deficiency, accompanied by an increase in the proportion of larger and less valent Mn ions as observed for other perovskite-type manganites upon reduction.44–46) Based on this argument, the oxygen deficiency in the P3 phase is expected to be much higher than that in the isostructural P1 phase.

To check the oxidation-state change of Mn, we have analyzed the K-edge XAS spectra of the fabricated samples, and used the XAS spectra of MnO (Mn2+), Mn2O3 (Mn3+) and Mn3O4 (the mixture of Mn2+ and Mn3+) as references. As addressed by Teo,47) a regular XAS spectrum can be divided into the pre-edge, X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES), and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) regions. Among these, the XANES region provides important information about the valence state of an absorbing atom. A shift of the absorption edge reflects the valence change of the an absorbing atom, meaning Mn in our case. As shown in Fig. 3, the Mn K-edge XANES regions of the samples range in the energy region E = 6542∼6558 eV. For LCMO, its absorption edge at ∼6551 eV located between 6548 eV of Mn2O3 and ∼6553 eV of MnO2.48) Meanwhile, the edges of LCMO-700 and LCMO-900 are almost the same at ∼6545 eV lying between the edges of MnO (∼6543 eV) and Mn3O4 (∼6346 eV). Notably, the whole XANES-region energy of LCMO-900 is slightly smaller than that of LCMO-700, and both XANES regions of these two samples occupy on the left of the edge of Mn2O3, see Fig. 3. These features reflect Mn3+ and Mn4+ ions coexisting in LCMO, in good agreement with previous works.34,49) Meanwhile, LCMO-700 and LCMO-900 have mainly Mn2+ and Mn3+ ions, and concentration of Mn2+ tends to increase when the annealing temperature increases. It means that Mn4+ concentration was rapidly decreased by hydrogenation. Reviewing oxygen-deficient perovskite manganites, we collected some following notes. Hossain et al.41) investigated La0.67Ca0.33MnO3−δ annealed in oxygen and reducing atmospheres in order to control the δ value, found the reduction of Mn4+ in oxygen-deficient samples. Similarly, Borca et al.43) studied La0.7Ca0.3MnO3−δ prepared in high vacuum and found the fabricated sample containing mostly Mn3+. For Mn2+, one found it locating at surfaces of La0.7Sr0.3MnO3 films.50) Thiessen et al.51) recorded oxygen reduction in La0.7Ce0.3MnO3 films reduced the Mn valence towards a 2+/3+ mixed state. It has been suggested that a detectable fraction of Mn2+/Mn3+ states is the trace of creating oxygen vacancies in perovskite manganites, which could result in the formation of the nano-sized brownmillerite structure.52) As studying LaMnO3 films, Pomar et al.53) observed the appearance of Mn2+ to form Mn2+[Mn3+]2O4 nanocrystals and the creation of a La-rich phase of La2MnO4, which help to compensate the stoichiometric imbalance. With those results, the mixed valence of Mn2+/Mn3+ found in our LCMO-700 and LCMO-900 samples are completely reasonable. These ions reside in the oxygen-deficient perovskite-type and Ruddlesden-Popper (La/Ca)2MnO4-type phases. Mn4+ ions could still exist in these samples, but its small amount is out of the instrumental detection limit.

K-edge XAS spectra of the fabricated samples compared with those of manganese oxides as references. The arrow shows the absorption-edge (Abs. edge) shift of Mn.

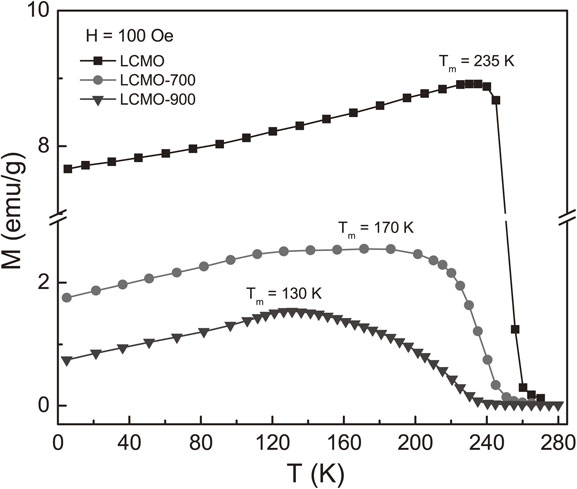

The changes in the structural characterization, the phase separation, and the oxidation state of Mn would remarkably influence the magnetic behaviors. Taking into account for these problems, we have performed M(T, H) magnetization measurements with T = 5∼280 K and H = 0–30 kOe. Herein, measurements were conducted as increasing T and H. Figure 4 shows zero-field-cooled M(T) curves of the samples in the field H = 100 Oe. At low temperatures, in the FM region, M of LCMO is several order larger than that of LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, indicating a rapid decrease in M induced by hydrogenation. With increasing T from 5 K, M gradually increases and achieves the maximum values at critical temperatures (Tm) of about 235, 170 and 130 K for LCMO, LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, respectively. At Tm, thermal energy (Et) is comparable to anisotropy-field energy (Ea) of FM/AFM clusters,54) which are also associated with the P2 and/or P3 phases in the hydrogen-annealed samples. This comparability in LCMO-700 at temperatures around Tm is more stable (resulting in a less change in M in a large range of T from ∼130 K), probably due to a large fraction of the P2 (Ruddlesden-Popper) phase (58.6%) with magnetic interactions competing with the P1 phase (41.4%), and both of them resists thermal activation. According a study of Fawcett et al.,55) Tm could also be related to Ruddlesden-Popper-type Ca2MnO4 with AFM states at TN ∼ 110 K,55) but the presence of La in (La/Ca)2MnO4 (P2) enhances TN towards Tm of LCMO-700 and LCMO-900. An increase in temperature above Tm (Et > Ea) would breaks exchange couplings between Mn ions, reduces M to zero, and causes the FM-PM transition. The FM-PM transition temperature (TC) could be estimated from the minima of the dM(T)/dT curves, as shown in Fig. 5. Here, we have found a decrease of TC from 251 K for LCMO through 240 K for LCMO-700 to ∼221 K for LCMO-900. While the phase transition of LCMO is very sharp, that of two other samples is fairly broad, particularly for LCMO-900. This proves the difference in their magnetic phase-transition characters. With the results of the structural analyses, we think that the additional appearance of the P2 phase in LCMO-700, and the P2 and P3 phases in LCMO-900 widened their FM-PM transition.

ZFC and/or FC M(T) data of the fabricated samples recorded in an applied field H = 100 Oe.

Plots of dM(T)/dT data for LCMO, LCMO-700 and LCMO-900. The inset shows the inverse susceptibility (χ−1 = H/M) at temperatures T > 100 K.

Apart from the widened transition-phase region, the mixed structural phases also lead to magnetic inhomogeneities. Graphing the inverse susceptibility data (χ−1 = H/M) at temperatures T > 100 K (the inset of Fig. 5), one can see an increase of the χ−1(T) data points above TC when the annealing temperature increases. In the investigated temperature range, χ−1(T) dependences of LCMO are linear according to the Curie-Weiss PM law χ−1(T) ∝ 1/(T − θ), where the CW temperature (θ) is about 254 K. However, the downturn in the χ−1(T) curves (some data above TC are departed from the Curie-Weiss (CW) law) are observed for LCMO-700 and LCMO-900. It is indicative of the Griffiths phase associated with FM/AFM clusters confined in the PM matrix.26,29,31) The downturn starts occurring at ∼261 and 250 K for LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, respectively, which are defined as the Griffiths temperatures (TG) of the samples. Above TG, their χ−1(T) data exhibit the pure CW PM behavior, with θ ≈ 230 K for LCMO-700 and 198 K for LCMO-900. It comes to our attention that θ of LCMO is slightly higher than TC, while for LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, their θ values are noticeably smaller than TC. Such features reflect that the FM interaction associated with Mn3+–O2−–Mn4+ double-exchange pairs in LCMO is much stronger than the FM interaction in LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, where Mn2+ and Mn3+ ions play a pivotal role. In other words, there is a strong competition between the FM and AFM phases in the hydrogen-annealed samples with the presence of oxygen-deficient perovskite-type and Ruddlesden-Popper-type phases, leading to a rapid decrease in M, as observed in Fig. 4. It has been assigned the (La/Ca)2MnO4 Ruddlesden-Popper phase P2 to be AFM.55) For perovskite manganites, the Mn3+–O2−–Mn3+ interaction is AFM.2,7,17,18) Because more Mn2+ content creates in LCMO-900 that reduces TC as comparing with LCMO-700, the Mn2+–O2−–Mn2+ exchange interaction also has the AFM character. Meanwhile, the multiple double exchange following the Mn3+–O2−–Mn2+–O2−–Mn3+ path proven in oxygen-deficient perovskite compounds is FM.56) As investigating hexagonal GaMnN, it has also found FM coupling between Mn2+ and Mn3+ ions.57) Depending on the Mn2+/Mn3+ ratio, dominant FM or AFM interaction would be representative of the magnetic properties of a sample.

We have also recorded M(H) in the vicinity of TC, with H = 0–30 kOe and temperature increments maintained at 3 K. M(H) data of LCMO with the first-order nature widely presented elsewhere indicate the S-shaped curves.31,33,36) For the two other samples (LCMO-700 and LCMO-900), their data are shown in Fig. 6(a), (c). Basically, M smoothly increases with increasing H, associated with the alignment of Mn magnetic moments to the magnetic-field direction. No S-shaped curves as the case of LCMO are also observed. When T increases, both M(H) magnitude and curvature gradually decrease because of the thermal decline of exchange interactions between Mn ions, similar to the M(T) variation around TC. Particularly, as plotting M2 versus H/M data, defined as inverse Arrott plots,58) one can see that the slopes of M2(H/M) curves of LCMO-700 at temperatures T > 240 K (T < 240 K) are negative (positive), while those of LCMO-900 are positive, see Figs. 6(b), (d). These features suggest that LCMO-700 has a mixture of the first- and second-order characters, while LCMO-900 has the second-order character only, according to Banerjee’s criteria.59) Here, the first-order nature in LCMO-700 could be related to the as-prepared LCMO crystals (TC ≈ 251 K) with almost no oxygen deficiency occupying inside the particles, while the second-order nature is related to the oxygen-deficient P1 phase (i.e., (La/Ca)MnO3−α) occupying the surface the particles, forming core/shell-type structures. Meanwhile, the second-order nature of LCMO-900 is ascribed to both oxygen-deficient perovskite-type phases P1 and P3. The Ruddlesden-Popper phase (P2, (La/Ca)2MnO4) with weak AFM interactions below Tm less influences the phase-transition characters of the hydrogen-annealed samples with TC ≫ Tm.

M(H) and inverse Arrott plots of two typical samples of (a), (b) LCMO-700 and (c), (d) LCMO-900, where temperature increments are 3 K.

Apart from considering the crystal structure, valence of Mn, and magnetic behaviors, we have also calculated absolute values of the magnetic-entropy change (|ΔSm|) versus T and H upon the M(H) data, and Maxwell’s equation:29,34,60)

| \begin{equation} |\Delta S_{m}(T,H)| = \int\limits_{0}^{H}\left(\frac{\partial M}{\partial T}\right)_{H}dH \end{equation} | (1) |

|ΔSm(T)| data of (a) LCMO-700 and (b) LCMO-900 for the field spans changing from 5 to 30 kOe. The inset plots |ΔSm(T)| data of LCMO at some field spans used for reference.

We have prepared polycrystalline LCMO, and then annealed it in hydrogen ambient at 700 and 900°C for 1 h in order to obtain the two samples of LCMO-700 and LCMO-900, respectively. XRD analyses upon the Rietveld method obtained the following results: (i) for LCMO, it has only the Pnma orthorhombic perovskite-type structure (P1); (ii) for LCMO-700, apart from the oxygen-deficient P1 phase, (La/Ca)MnO3−α, there is the formation of the Ruddlesden-Popper (La/Ca)2MnO4-type phase (P2); for LCMO-900, besides P2, there coexists of perovskite-type phases with different oxygen contents (La/Ca)MnO3−α (P1) and (La/Ca)MnO3−β (P3), with α < β. Together with the structural phase segregations, the hydrogenation also led to the valence shift of Mn3+/Mn4+ (in LCMO) → Mn2+/Mn3+ (in LCMO-700 and LCMO-900). These factors changed magnetic exchange interactions (i.e., Mn3+,4+–O2−–Mn3+,4+ → Mn2+,3+–O2−–Mn2+,3+ and Mn3+–O2−–Mn2+–O2−–Mn3+), caused magnetic inhomogeneities, developed the Griffiths phase, and reduced the values of TC, M and |ΔSm| (|ΔSmax|) characteristic of the magnetic and MC behaviors. Concurrently, the first-to-second order phase transition has also been taken place.

This work was funded by Vingroup Joint Stock Company (Vingroup JSC), Vingroup and supported by Vingroup Innovation Foundation (VINIF) under project code VINIF.2020.DA18. The research was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant No. 2020R1A2C1008115. The work was also supported by National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government’s Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT, 2020R1A2B5B01002184).