2023 Volume 64 Issue 9 Pages 2134-2142

2023 Volume 64 Issue 9 Pages 2134-2142

Binary copper oxides with different copper ion oxidation states including cuprous Cu2O and cupric CuO have already been successfully synthesized by the simple and highly repeatable grow-up technique from the modified copper Cu sheet. By controlling the annealing time and temperature, the copper oxide (CuO, Cu2O) composites were hierarchically formed on Cu surface. All obtained samples were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The results showed that the modified Cu sheets after annealing in air yielded the mixture of CuO and Cu2O phases. The obtained Cu2O/CuO composites have been used as active photocatalysts to decolourize the 10 ppm dyes rose bengal solution with the degradation efficiency of 73% over a period of 3 h under UV-A irradiation after three uses. These results make them attractive as reusable photocatalytic materials in form of flat sheet. The other testing conditions as pH values and oxidant agent (H2O2) was carried out. It was observed that the photodegradation achieved up to 96% with the presence of H2O2.

Water pollution treatment by photocatalytic technology has been achieving great progresses.1,2) However, some high requirements as visible light absorption, good charge separation, reusability and stability as well as environmental benignity have been still expected. Semiconductors including various oxides and sulfides, have been synthesized and used for the removal and degradation of organics in water sources (i.e. antibiotics in natural waters, dyes in industrial waters,…) due to their compositional simplicity and stoichiometric diversity. Among metal oxides, cupric oxide (CuO) and cuprous oxide (Cu2O) are low cost, abundant resources, non-toxicity, and chemical stability.3) Additionally, they are the p-type semiconductors have relatively narrow and direct bandgaps of 2.0–2.5 eV and 1.2–1.7 eV, respectively.4,5) Their small bandgap energies allow them to absorb a broad range of solar spectrum with a large absorption coefficient.4) CuO possesses synergistic effects when coupling with Cu2O as well as improves the kinetic stability of Cu2O. Since both conduction and valence band edges of Cu2O are at more negative potentials than those of CuO, the photogenerated electrons in conduction band of Cu2O will be injected into that of CuO at the Cu2O/CuO interface under visible-light irradiation.5,6) Besides, the photogenerated holes in valence band of CuO are injected into that of Cu2O. As a result, the Cu2O/CuO heterojunction facilitates the electron-hole separation.

Cu2O, CuO, and/or Cu2O/CuO have been generally studied for gas sensors, photodetectors, photovoltaic, and supercapacitor applications.7) Recently, some studies have reported the application of both CuO and Cu2O as photocatalysts for the photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants in aqueous media. The CuO–Cu2O heterojunction thin films were used for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue (MB) under the visible light.6) The CuO/Cu2O heterostructure with different morphologies of CuO crystals (nanowires, nano-tetrahedra, and nanospheres) significantly improved the methyl orange (MO) degradation under visible irradiation.8) Different morphologies of CuO have resulted in dramatic effects on photocatalytic activity and stability of CuO/Cu2O system. In other study, heterostructure photocatalyst of CuO–Cu2O was also prepared in which the impact of the Cu2O content on the photocatalytic activity and mechanism was investigated by the MB and MO degradation under the visible light irradiation.9) The degradation efficiency was increased by the higher content of Cu2O. Qing Jiang’s group reported the preparation of CuO/Cu2O composite particles that exhibited as high as 97% photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B (RhB) in 5 minutes under visible light in the presence of H2O2.10) As the noticeable report, Zhang’s group mentioned the composite of in situ grown CuO–Cu2O over graphene oxide (GO) surface which enhanced the photocatalytic capacity to degrade tetracycline and methyl orange when comparing with CuO–Cu2O nanoparticles.11) The abundant exposed adsorption and reaction sites from the GO protective layer for CuO–Cu2O in the heterojunction were confirmed to promote the high photogenerated electron-hole transport with high catalytic surface area. As the further review, the bi-component material from the heterostructure of Cu2O–CuO in functions to degrade organic compounds was confirmed to be better than that of individual Cu2O or CuO.12) However, the reduction of the photocatalytic functions with the reunitition of each component and the instability of Cu2O are formidable challenges to obtain the perfect materials.

In the same contest but into the different purposes, some publications mentioned the role of copper oxides (CuxO) with nanostructure of flower and needle shapes to enhance the onset potential and redox current as the results in the improvement of the effectively electrochemical density and surface area for a superior catalytic performance.13) Xu’s group also mentioned that the microstructure of copper oxides over Cu surface affected charge-transfer/ion diffusion resistance and reaction kinetics on the surface.14) The electrochemical behavior of the CuxO/Cu system could be considered as a clear clue to confirm the electron-hole interaction in water phase under light exposure. Bayat et al. also did some exploration for the relationship between the ratio of CuO/Cu2O and the photocatatalitic ability under the visible light.15) The present of •OH was considered as the more effective oxidative agent to degradate the dye methylene blue, accompanying of higher amount of Cu2O which can enhance the photocatalytic performance in visible light while the higher amount of CuO reduce that with the photodegradation yield of 32%.

Besides, an additional solution to get over the backdraw from the Cu2O–CuO bilayered composites in the reusability and stability of photocatalytic materials should be noticed. Thus, photocatalyst based thin film will provide a feasible option for water and wastewater treatment applications.16–18) They will improve the recovery efficiency of photocatalysts after water treatment while avoiding their consequent dispersion in water. Obviously, they will lessen the technical and financial burdens but have been rarely reported in the previous publications.

Due to the higher popularity of CuO than Cu2O in normal conditions and the low effective photodegradation of CuO in visible light, we focused on enhancing the photocatalytic performance of the heterostructure of Cu2O–CuO with the small amount of H2O2 as the resource of •OH and the exposure under the UVA light which is highly commonplace in the sunlight (up to 95% of the sun’s UV ray). The effect of the flexible exchange between the oxidation levels of copper (0, 1+, 2+) under the excitation from UVA light have not been mentioned in the photodegradation before. The presence of Cu metal from the regrid supporter with multiple oxidation states may also play an important role to efficiently absorb higher energy wavelengths (UV light) than capacities of each Cu2O (visible light) or CuO (infrared-red light), individually. The thin copper sheets were utilized to grow CuO/Cu2O crystal mixture on their surface by an easy oxidation route. In addition, in order to obtain films with different contents of CuO and Cu2O phases, the as-oxidized CuxO films are subsequently annealed in air at temperatures of 100–500°C for 1 to 8 h. Furthermore, not only the morphological and structural properties of the films are characterized but also the photocatalytic properties are investigated. In addition, the influence of thermal annealing on the relationship among morphological, structural, and photocatalytic properties are discussed.

All chemicals were of analytical grade without further treatment. Copper (Cu) sheets (≥ 99%, China), sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (≥ 96%, Merck), ammonium persulfate (NH4)2S2O8 (≥ 98%, Merck), rose bengal (≥ 99%, Sigma-Aldrich).

2.2 Growth of CuO/Cu2O composites on Cu sheetsCopper sheets of 1 mm thick were cut into sizes of 2 × 5 cm2 and cleaned with distilled water and alcohol, and then used as substrates for the further CuO/Cu2O crystal mixture growing process. After cleaning, the copper sheets were immersed in the solution mixture of 20 mL (NH4)2S2O8 (0.2 M) and 20 mL of NaOH (2.5 M) for 30 minutes. Cu(OH)2 were formed by in-situ oxidation on the surface of Cu sheets. The oxidized Cu sheets were then carefully cleaned with distilled water, and naturally dried at ambient temperature. The formation and growth of CuO/Cu2O crystal mixture was performed by annealing the oxidized Cu sheets in a furnace at various temperatures (100°C, 300°C, 400°C, and 500°C) for different durations (1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 h), thereafter naturally cooled to room temperature.

In this work, ammonium persulfate (NH4)2S2O8 was used as an oxidizing agent, and CuO/Cu2O mixed products were formed according to the following reaction steps:

| \begin{align} &\textit{Cu} + (\textit{NH}_{4})_{2}S_{2}O_{8} + \textit{NaOH}\\ &\quad \to \textit{Cu}(\textit{OH})_{2} + (\textit{NH}_{4})_{2}\textit{SO}_{4} + \textit{Na}_{2}\textit{SO}_{4} \end{align} | (1) |

| \begin{equation} \textit{Cu}(\textit{OH})_{2}\xrightarrow{T}\textit{CuO} \end{equation} | (2) |

| \begin{equation} \textit{CuO} + \textit{Cu}\xleftarrow{\to}\textit{Cu}_{2}O \end{equation} | (3) |

The structural and morphological properties of CuO/Cu2O crystal mixtures were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Bruker diffractometer XRD D5005) employing CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI Nova NanoSEM 450).

2.4 Photocatalytic testingThe CuO/Cu2O@Cu sheets were set up at an angle of 10° against the wall of the 250 mL batch-photoreactor containing the 250 mL of 10 ppm RB solution as a model pollutant (Fig. 1). The photoreactor was placed in a stainless-steel box, where a small fan and a UV-A light system with a total power of 90 W were set on the top, respectively, to avoid evaporation during the photocatalytic experiments. To recirculate the flow of RB dye solution during the photocatalytic reaction, a mini peristaltic pump and a 250 mL beaker were used. Before UV illumination, whole RB solution and photocatalyst were maintained in darkness for 30 minutes to establish the adsorption-desorption equilibrium. The solution in the beaker was stirred by a magnetic bar.

Experimental setup used in the photodegradation of rose bengal.

The treated RB solution was collected over a period (15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 4 h, 5 h) and determined the corresponding absorbance (A) by a UV-1800 Shimadzu spectrophotometer at the wavelength of 547.5 nm. The photodegradation efficiency of rose bengal (H) was calculated by the formula:

| \begin{equation*} H = \frac{A_{0} - A_{t}}{A_{0}}.100\% \end{equation*} |

X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement was carried out to identify crystal structure and phase composition of the CuO/Cu2O crystal mixture obtained after annealing from 100 to 500°C for 1 h. The mixture phase of CuO and Cu2O was detected in all samples after the annealing. In more detail, before the annealing the XRD pattern (Fig. 2(a)) shows two clear peaks appeared at 16.79° and 23.88° (Fig. 2(a)_left) representing to Cu(OH)2 phase (JCPDS No. 35–0505) and a strong peak located at 50.41° (Fig. 2(a)_right) corresponding to the metallic Cu (JCPDS No. 04–0836) that also appeared in all XRD patterns of all samples. For thermally treated samples (Fig. 2(b)–(e)_right), diffraction peaks at 29.63°, 36.28°, and 42.14° are attributed to (110), (111), (200) planes of Cu2O phase (JCPDS No. 05-0667) and the rest of diffraction peaks can be assigned to monoclinic CuO structure, 32.43°, 35.47°, 38.66°, 48.74°, 53.38°, and 58.27° corresponding to (110), (11-1), (111), (20-2), (020), and (202) planes of CuO phase (JCPDS No. 45–0937), respectively.

The influence of annealing temperature on the structural properties of CuxO films: (a) 25°C, (b) 100°C, (c) 300°C, (d) 400°C, (e) 500°C.

The CuO formation was observed by two strong diffraction peaks at 35.47° and 38.66° with an increase of annealing temperature from 100 to 400°C. At the higher temperature (500°C), their intensity dramatically decreased. Meanwhile, the Cu2O phase was gradually crystallized by the appearance of the broad diffraction peak at 29.63°, the relatively weak signal at 36.28° that overlapped with that of CuO, and the other at 42.14°. Noticeably, an intense Cu2O peak at 36.28° with the dominant orientation of (200) plane clearly appeared in the XRD pattern of sample calcined at 500°C with the high intensity when comparing relatively with ones of the other peaks from Cu2O phase at 29.63° and 42.14°, and from the CuO phase at 35.47° and 38.66°. Hence, we hypothesize the Cu(OH)2 intermediate was formed, and it had different chemical affinity to CuO and Cu2O as well as inherent growth orientation leading to the competitive appearance between CuO and Cu2O consequently. The Cu2O crystals grew quickly in both the quality and quantity, finally covering the wire form of CuO phase over the surface of the Cu sheet, which caused the reduction of the CuO signals in XRD pattern (Fig. 3 and Table 1). In addition, the obtained results suggest the formation of a thin Cu2O layer on the CuO layers over Cu sheet with the ratio of CuO/Cu2O depending on the annealing temperature.

Fitting plots of diffraction peaks at 35.47° and 36.28° corresponding to CuO and Cu2O phases, respectively, fitted to the Gaussian function of samples calcined at 100°C, 300°C, 400°C.

The formation of Cu2O/CuO heterolayers was also investigated on the annealing time. Figure 4 shows the XRD patterns of samples calcined at 400°C for different durations (1–8 h). The overlap of Cu2O and CuO phases was maintained. The same tendency was obtained. The dominated formation of CuO phase in the very early stage was observed (Fig. 4(a)), and then it was partly transformed to Cu2O phase. The more annealing time prolongs the more Cu2O phase forms. With annealing time of 8 h, the most intense peak of Cu2O was clearly observed at 36.28°.

The influence of annealing time on the structural properties of CuxO films calcined at 400°C for (a) 1 h, (b) 2 h, (c) 3 h, (d) 5 h, (e) 8 h.

CuO and Cu2O phases were not easily distinguished from each other at early stages (calcined below 500°C or for 1–2 h) due to the proximity of the associated components. The detailed their growth processes were investigated by SEM images as presented in Fig. 5–7. The SEM image of Cu(OH)2 wires shows the uniform dense 1D structure morphology and the wires array is roughly vertically grown on the Cu surface (Fig. 5(a)). The wires are several tens to over one hundred nanometers in width and a few micrometers in length. Figure 5(b)–(e) show the SEM images of Cu2O/CuO crystal mixtures formed during the annealing process in air at various temperatures of 25°C (room temperature), 100°C, 300°C, 400°C, and 500°C. Compared with the SEM image of Cu(OH)2 wires, it can be seen that the wires become more in number and longer in length, and get a little bent due to the dehydration of Cu(OH)2 to CuO and Cu2O during the annealing. Additionally, flower-like crystals were parallelly formed with a diameter of a few micrometers uniformly. The magnified image of a single micro-flower shows that it consists of dense nanosheets with thickness of about 50–100 nm. The higher annealing temperature did not change the morphology of Cu2O/CuO-mixed samples, but did increase the ratio of flowers/wires form which absolutely matched the results of the XRD patterns in Fig. 2(e) with the majority of Cu2O phase. We confirmed that the wire form might be in the CuO phase while the flower form may be in the Cu2O form that was covered majorly over the surface of the system responding to the higher ratio of Cu2O/CuO in relatively XRD peaks intensities at 35.47° and 36.28°.

The influence of annealing temperature on the morphological properties of CuxO films: (a) 25°C, (b) 100°C, (c) 300°C, (d) 400°C, (e) 500°C, and (f) high magnification for sample annealed at 500°C.

The influence of annealing time on the morphological properties of CuxO films calcined at 400°C for 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, 8 h (low magnification).

The influence of annealing time on the morphological properties of CuxO films calcined at 400°C for 1 h, 2 h, 3 h, 5 h, 8 h (high magnification).

The stability of Cu2O in the annealing conditions at higher temperature (400°C and 500°C) and longer time as shown in Fig. 6 and 7 in air should be noticed particularly because CuO can be prioritized to react with oxygen in air immediately to form Cu2O phase, in fact the amount of Cu2O increased with higher annealing temperature. That can be explained by the advance from the micro-flower form with many small and thin flats folded together in term of “closest packed structures” leading to a decrease in surface area that exposed to air atmosphere during heating treatment. On the other hand, we supposed a hypothesis that the melting occurred at the edge of the CuO wire near the Cu surface to encourage the thermal fusion of Cu metal atoms into the lattices of CuO to form Cu2O and extend its morphology into flat form. These flat crystals appeared in all directions to create the micro-flower form where all flat crystals folded together. A good agreement with growth mechanism and reactions at the interface between oxide phases has been proposed in a new publication.20) At the interface, the oxide phases are in the following equilibrium:

| \begin{equation*} \text{CuO} + \text{Cu} \rightleftharpoons \text{Cu$_{2}$O} \end{equation*} |

The ability of as-synthesized materials in degrading pollutants was tested with dyes rose bengal (RB) chosen as a model organic compound for the treatment of wastewater at very low concentration (∼ppm). Rose bengal is a water-soluble, halogen-containing, fluorescent hazardous dye and has adverse toxic effects.19) It is a triarylmethane dye, which contains triphenylmethane backbones. Photocatalytic performances of the as-synthesized copper oxide samples were evaluated by monitoring the changes observed in the absorption spectra of RB and its decolourization during reaction under low concentration of 10 ppm. Figure 8(a) and (b) summarizes the results of these studies over the Cu2O/CuO-mixed crystals samples obtained after annealing at various temperatures for different durations. Normally, CuO and Cu2O materials could be considered as active photocatalysts under the visible light range. Especially for this work, it shows that all samples are active under the UVA-illumination for 180 minutes. Among them, the sample annealed at 400°C for 3 h exhibited the best photocatalytic property with the photodegradation yield of 73% (Fig. 8(c) and (d)).

The influence of annealing conditions on the photocatalytic properties of Cu2O/CuO/Cu samples: (a) temperature and (b) time. (c) The change in absorption spectra and (d) percentage of decolourization of RB dyes solution over Cu2O/CuO/Cu sample annealed at 400°C for 3 h.

In the Fig. 8(c) and (d), the RB photodegradation over Cu2O/CuO-mixed crystals sample obtained after annealing at 400°C took place rapidly in the first 60 minutes (up to 62%), then gradually decreased until the end of reaction, finally reached about 73% after 180 min. Besides the decrease in intensity of 547.5 nm peak, its blue-shift suggests the formation of intermediates during the photocatalytic reaction. Before UVA-illumination, the testing system was always maintained in the darkness for 30 minutes to balance the adsorption-desorption of rose bengal molecules on the surface of photocatalytic samples. Therefore, the decrease in decolorization speed after the first 60 minutes can be explained that the active radicals as O2•−, OH•, O• from the interaction between the Cu2O/CuO surface and the UV light were captured by the intermediates or the intermediates blocked the surface of Cu2O/CuO. That had high agreement to the results of XRD patterns and SEM images. The micrometer structure of the sample calcined at 400°C consisted of thin, long wires and flower-like crystals foamed on the Cu surface could play two roles for the photocatalyst to decolorize the dye RB. The first, the interaction between the two oxidation stages of copper at +1 (Cu2O) and +2 (CuO) could be the bridge to transfer electrons in the system to promote the absorption of the UV-A light, then to devolve the energy into smaller one which may be suitable for the formation of the active radicals based on the in-house electronic structure of the materials. The latter, the foam form of the system with a lot CuO wires interleaving each other and the multilayer of small flat from flower form could be good spaces as mini-reactor for compound transferring.

To estimate the environmental factors on the RB photodegradation, the various values of pH were applied. We used HCl 0.1 M and NaOH 0.1 M to adjust the pH of the solution, then slowly dropped them into the reaction solution before performing the experiment over the Cu2O/CuO mixture film. The results of decolourization at various pH values were presented in Fig. 9. There are minor differences among the decolouring processes over different pH values with the decolouring yields among 68 to 74%. In the case of the lowest pH at 3.5, there was a similarity to the reactions at the other pH in the first 30 min. After that, from 30 min to 90 min, the rate of the decomposition decreased, and then increased again after 90 min reaction time to reach the same decomposing yield of RB at 68%. The best result to degrade RB up to 74% with pH at 7.5 after 180 min reaction time. Therefore, it can be concluded that CuO can work for photodegradation in solution at various pH values. That can be the advantage point for this material to further applications.

The effect of pH on the photodegradation of RB over Cu2O/CuO crystal mixtures annealed at 400°C.

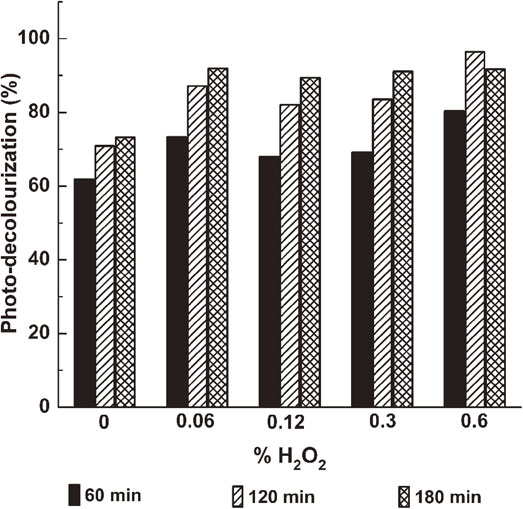

We supposed that the presence of oxygen is one of the main factors in the photodegradation, so we added various H2O2 amounts as an alternative oxidant before operating the photocatalytic reaction. Figure 10 shows that the presence of H2O2 in the nitrogen atmosphere facilitated the photocatalytic reaction. In detail, when the concentrations of H2O2 were 0.06%, 0.12%, and 0.30%, the decolouring yields were 84%, 86%, and 88%, respectively, compared with the case without using H2O2 (74%) after 2 h of UVA irradiation. To verify the role of photocatalyst, the reactions were repeated with the same conditions but without photocatalyst. As a result, there was no decomposition of RB with the concentration of H2O2 at 0.06%, 0.12%, and 0.30%.

The effect of H2O2 adding on the photodegradation of RB over Cu2O/CuO crystal mixtures annealed at 400°C.

For the concentration of H2O2 was at 0.60%, the decolouring yield got the best result, about 96% RB was degraded after 2 h under UVA irradiation which was higher than the results reported in Ref. 15) (32% yield). However, the degradation rate decreased after 3 h of reaction. At the higher concentration of H2O2 (> 0.60%), we could observe the decomposition of the RB reaching 96% yield without photocatalyst. The reactions with and without photocatalyst were accompanied with the presence of bubbles from the decomposition of H2O2 into O2. In addition, the reaction between the RB and H2O2 without photocatalyst did not occur in the darkness.

After all, we supposed that the Cu2O/CuO/Cu system played the role of the catalyst as a photo-Fenton agent with the low concentration of H2O2 to decolorize the dye rose bengal. With higher concentration of H2O2 over 0.6%, the decomposition of H2O2 under UV-A light got advantages to promote the RB decolouring.

To evaluate the capacity of Cu2O/CuO mixture for the scale up testing application, the reusability of this sample was tested for three cycles. Figure 11 presents the degradation percentage from the three cycle tests using sample annealed at 400°C for 3 h. As can be seen, the degradation percentage was repeatable (73%, 74%, and 72%, respectively). The reduction in photocatalytic degradation percentage after three cycles was less than 5%. Stability and durability of the sample are not affected much by the testing cycles. The surface morphology and crystal structure results of the sample after testing were checked by Raman scattering and XRD measurements (Fig. 12). It was clear that the morphology on the reused material surface had difference from the pre-used one on which the flower like Cu2O appeared less and the wire-like CuO increased in the area ratio. It may come from the instability of Cu2O which can be easy to transform into the CuO or come back to Cu metal when interaction with oxidative agents or reduction agent like oxygen, and radicals. The upper position of Cu2O flower-like clusters on the surface may also be in advantage because they can be removed from the photocatalyst surface due to the mechanic interaction with the flowing solution. We saw a very small amount of black precipitation on the bottom of the testing beaker after each recycled cycle. Fortunately, the change above did not influence into the excellent decoloring property of photocatalytic materials which is totally in agreement with our previous conclusion that the small appearance of Cu2O led to the improvement of photocatalytic decoloring of the Cu2O/CuO/Cu system photocatalysts.

Reusability of Cu2O/CuO mixture under UVA light irradiation during RB degradation.

(a) Raman spectra and (b) XRD patterns of Cu2O/CuO/Cu system before and after testing for 3 cycles, (c), (d) SEM images after testing for 3 cycles.

The relationship between the morphology of CuO and Cu2O, the components of CuO/Cu2O grown up on the surface of Cu sheets, and the annealing conditions (time and temperature) was investigated to optimize the best material for high-photodegradation of dye rose bengal. The best sample was obtained with the mixture of CuO and Cu2O crystals covering the surface of copper sheets. The Cu2O/CuO composite increases the ability to decolour the rose bengal up to 74% with various pH values from 3.5 to 10.5, and up to 90%, 96% in the addition of 0.30%, 0.60% H2O2 to RB solution, respectively. The simple preparation and renewability of the Cu2O/CuO/Cu system make it an active photocatalytic material in decolouring the dye agents.

This research is funded by Viet Nam National Foundation for Science and Technology Development via grant no. 103.99-2020.33. Also, we would like to thank the National Key Laboratory for Electronic Materials and Devices, Institute of Materials Science, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology for photocatalytic experiments; laboratories from the Faculty of Physics and Chemistry, VNU - Hanoi University of Science, Vietnam National University for material synthesis, XRD, SEM, and UV-vis spectroscopy measurements.