2025 年 13 巻 4 号 p. 75-91

2025 年 13 巻 4 号 p. 75-91

Phytophthora capsici is a significant pathogen that causes foot rot disease in black pepper, leading to considerable yield losses. Although chemical fungicides are effective, they pose environmental and health risks. Conversely, botanical fungicides derived from plants offer an eco-friendly alternative. However, their efficacy may be inferior to that of conventional chemical fungicides in certain applications. This paper evaluated the mode of action and efficacy of several botanical pesticides as alternatives for managing P. capsici infections in black pepper, emphasizing the potential of these biopesticides as sustainable disease management tools.

Black pepper, often referred to as the “King of Spices”, is a critical cash crop in many tropical countries, especially in Indonesia. Recently, Indonesia’s pepper production has declined at an average annual rate of about 0.6% between 2013 and 2022. Pepper productivity, in both smallholders and state-owned farms, remains relatively low at less than 1 ton per hectare. The pepper production from smallholder plantations in 2023 was 70,200 tons, a decrease of 6.65% compared to the previous year. Smallholder plantations contribute up to 96.81% of Indonesia’s total pepper production [1]. This decline in pepper production has led to a decrease in pepper exports, from 13,182.2 tons to 9,276.2 tons (a 29.63% drop) [2]. To address this issue, efforts are being made to improve pepper productivity through the use of seed technology, processing efficiency, and better cultivation practices. However, black pepper cultivation is severely constrained by Phytophthora capsici, a soil-borne oomycete that causes foot rot and substantial yield losses.

Phytophthora capsici, as one of the most destructive and widespread phytopathogens, is a major problem in black pepper cultivation worldwide [3]. A recent study in India revealed that the economic loss due to P. capsici infection in black pepper reached USD 902.04/ha [4]. Under favorable environmental conditions and in the absence of effective control, this pathogen can cause total yield loss [5]. Similar conditions were also reported in Bangka Regency, one of the centers for black pepper production in Indonesia. The disease severity due to P. capsici infection was as high as 43.11% [6]. Vietnam, as the world’s largest peppercorn producer, is also facing the same threat. In 2020, Nguyen et al [7] reported that the P. capsici infection caused pepper production to decrease around 15–20% per year.

Conventional management of P. capsici relies heavily on synthetic fungicides. These fungicides usually contain one or more active ingredients that are already proven to be able to control the pathogen. Permana and Diyasti [8] reported that fungicides containing phosphite acid have an efficacy rate of 30.06 % in controlling P. capsici, while the efficacy rate of the mancozeb, azoxystrobin, and klorotalonil was 28.23%, 29.01% and 4.13% respectively. Each active ingredient operates through a distinct mode of action. Phosphite acid (H₃PO₃) is the reduced form of phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) and has a structure that allows this compound to interact effectively with plants and pathogens. Phosphite interferes with oomycete metabolism by disrupting enzymes involved in respiration and ATP synthesis [9], as well as by inhibiting spore germination and zoospore motility [10]. The phosphite acid also has the ability to move systemically in plants. After applying, phosphite can move upwards (from roots to leaves) or downwards (from leaves to roots), thus protecting all parts of the plant from pathogen infection [11, 12]. Phosphite application can elevate levels of chlorogenic, caffeic, and salicylic acids, which play key roles in plant defense [13]. Although it is considered a low-toxicity fungicide to humans, further study about the environmental buildup effect still needs to be investigated.

One of the most commonly applied fungicides to control P. capsici is mancozeb. It works by inhibiting enzyme activity in fungi, hence disrupting their metabolism [43]. It also works as a nutrient-chelating agent, therefore inhibiting fungal growth. Mancozeb is a combination of two essential metal elements, namely manganese (Mn) and zinc (Zn), with a dithiocarbamate group. The dithiocarbamate group in Mancozeb can bind to the sulfhydryl groups of fungal enzymes, thereby disrupting enzyme function and stopping fungal growth [15]. According to the Fungicide Resistance Action Committee (FRAC), mancozeb is classified as an M3 fungicide, generally considered a low-risk group with no evidence of cross-resistance [16]. However, recent study revealed that it exhibits aquatic toxicity that causes developmental malformations in zebrafish [17].

Another fungicide that is commonly used in black pepper cultivation is azoxystrobin. The fungicide was applied in the nursery to prevent seedling blight caused by P. capsici [18]. Azoxystrobin is a systemic fungicide from the strobilurin group [19]. Strobilurin is a compound inspired by a natural compound produced by the fungus Strobilurus tenacellus [20]. The mechanism of action of this fungicide is to bind to the complex group located in the inner mitochondrial membrane of fungi and other eukaryotes, thereby blocking the transfer of electrons that will disrupt the energy cycle in fungi by stopping ATP production [19]. In other words, mycelial growth, spore germination, and sporangium formation in Phytophthora capsici can be inhibited [21]. Azoxystrobin is one of the most widely used in the world because of its effectiveness and broad spectrum of action. Previous study revealed that azoxystrobin was not only effective in controlling Phytophthora [21] but also Colletotrichum capsici, Botrytis cinera, Rizoctonia solani, and Magnaporthe grisea [22]. In addition, azoxystrobin is effective against Fusarium fujikuroi [23], Aspergillus niger (peanut collar rot disease) [24], Plasmopara viticola (downy mildew disease) [25], as well as Uncinula necator (powdery mildew disease) [26]. However, recent findings revealed azoxystrobin-resistant P. capsici that start causing pepper blight in China [27].

Metalaxyl is another highly effective systemic fungicide against oomycetes such as Phytophthora [28]. Due to its effectiveness, metalaxyl was recommended for the management of wilting disease of black pepper caused by P. capsici [29]. The fungicide strongly inhibits the incorporation of nucleotides into nucleic acids [30]. Metalaxyl also works by inhibiting uridine incorporation into RNA and specifically inhibiting RNA polymerase [31].

Although synthetic fungicides are effective, they contribute significantly to environmental pollution. Mancozeb has been proven to affect soil microflora, the nitrification process, soil biomass, carbon mineralization, and soil enzymes [32], which in turn would have a negative impact on nutrient uptake and plant growth. Metalaxyl is also considered as a potential threat to the environment due to its carcinogenic and mutagenic nature toward the mammals and aquatic organisms. Previous study showed that the fungicide metalaxyl might have inhibited the growth of Solanum nigrum due to impairment of photosynthesis caused by the decrease of amount and activity of the Rubisco enzyme [33]. Several studies have reported that prolonged use of mancozeb would cause ethylenethiourea (ETU) buildup [34]. ETU is recognized as a hormone disruptor, teratogenic, mutagenic and carcinogenic compound [35]. Some studies also stated that long-term exposure to mancozeb might have premalignant changes in human ovaries, impair reproduction at the cellular level, damage DNA, and initiate tumors in fetal cells, which might lead to infertility or at least complicate pregnancy [36, 37]. Fungicide use often results in the accumulation of considerable residues. Azoxystrobin exhibits hepatotoxic effects in mammals [38] and induces genotoxicity and oxidative stress in aquatic organisms [39]. Mefenoxam exhibits low to moderate acute mammalian toxicity, corrosive eye irritation and dermal irritation [40]. While azoxystrobin is less toxic than metalaxyl, azoxystrobin left a higher amount of residue in multiple foods [41, 42]. Given the documented adverse effects associated with synthetic fungicides, there is an increasing need to explore safer and more sustainable alternatives. Botanical fungicides, derived from plant-based compounds, offer a promising approach due to their biodegradability, lower toxicity, and potential for integration into environmentally friendly pest management strategies.

Botanical fungicides, derived from plants with pesticidal properties, have been used as alternatives in plant disease management. The active ingredients in botanical fungicides generally come from plant extracts, essential oils, gums, resins, and others that have natural antimicrobial or antifungal properties [43]. These active compounds are secondary metabolites produced by plants in the form of phenolics, fatty acids, flavonoids, alkaloids, glycosides, terpenoids, and tannins [44]. Previous study reported that cinnamon oil showed a fungicidal effect at all concentrations, neem oil showed a decrease in the growth of F. solani and F. oxysporum by 42.3% and 27.8% and was able to inhibit the growth of P. capsici mycelium by 53.3% and Goetrichum sp. by 20.9% and black sapodilla extract inhibited 21.9–28.6% of the growth of all fungi [45]. Botanical fungicides are in high demand because they are more environmentally friendly and have a low residual impact compared to synthetic fungicides.

Botanical fungicides are persistent and easily degradable. It causes no harm to the soil microbial composition and helps in maintaining soil properties. The botanical fungicides also lack cross-resistance due to their different modes of action from synthetic fungicides. Moreover, it is also known to have a minimum negative impact on the physiological process of plants [44]. These characteristics make botanical fungicides advantageous over synthetic fungicide.

The growing interest in botanical fungicides is largely driven by the need for safer and more sustainable alternatives to synthetic chemicals, which pose environmental and health concerns. As awareness of these adverse effects increases, research efforts have intensified to identify plant-derived compounds with potent antifungal activity. The demand for botanical fungicides is further supported by their compatibility with ecological farming practices and their potential role in integrated pest management (IPM) systems. This shift toward botanically based solutions provides an opportunity to harness naturally occurring bioactive compounds for effective disease control, particularly in the management of soil-borne and foliar pathogens.

These natural products are biodegradable, less toxic to non-target organisms, and reduce the risk of resistance development in pathogens. This paper reviews the effectiveness of various botanical pesticides against P. capsici in black pepper, emphasizing their mechanisms of action, application methods, and potential integration into sustainable pest management strategies.

Phytophthora capsici threatens black pepper at nearly all growth stages. Although P. capsici is not typically seedborne, the seedling blight of black pepper is one of the major diseases in black pepper nurseries [18]. Infected nursery conditions or contaminated tools and irrigation water can facilitate early-stage infections. In poorly drained nurseries, zoospores can quickly infiltrate the root zone, causing root necrosis and reducing seedling vigor. Infected seedlings often exhibit chlorosis, wilting, and root rot, which severely limit their establishment upon transplantation [46].

Nursery environments are particularly conducive to P. capsici proliferation due to the dense planting arrangements, frequent irrigation, and high humidity. Contaminated soil, organic matter, and water sources act as reservoirs for inoculum buildup [47]. The pathogen primarily infects the root system, but under favorable conditions, it may also reach the collar and stem base. Asymptomatic infections during this stage may predispose young plants to severe diseases that outbreak post-transplantation.

In field conditions, P. capsici causes the most recognizable and economically damaging disease known as foot rot or quick wilt [48]. Initial symptoms include leaf yellowing and wilting, which rapidly progress to defoliation, blackening of stems, and plant death within days [49]. The pathogen enters through natural openings or wounds, colonizing vascular tissues and disrupting water transport [50]. The extensive root damage impairs nutrient and water uptake, further weakening the plant [51]. Continuous cropping and lack of rotation could lead to the buildup of inoculum in the rhizosphere. Secondary infection through rain splash or irrigation water can lead to aerial blight, where lesions form on leaves and stems [52]. The pathogen can also survive in plant debris and soil as chlamydospores or oospores for up to 19 months without a host [53], making eradication difficult without proper field sanitation and crop management practices.

Botanical fungicides exert their effects through two primary mechanisms: direct antifungal activity and the induction of plant systemic resistance. Direct antifungal activity involves the inhibition of fungal growth, spore germination, and mycelial development. In addition to this direct toxicity, many botanical extracts have been shown to enhance the plant’s innate immune response by triggering systemic acquired resistance (SAR) or induced systemic resistance (ISR).

3.1 Direct antifungal propertiesPlant-based fungicides contain compounds such as alkaloids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and phenolics, which exhibit antifungal properties. A recent study showed that alkaloids could change the mycelial morphology of P. capsici, revealing swollen, fragmented, or deformed hyphae after the treatment (Fig.1) [54]. This is due to the ability of alkaloids to inhibit beta 1,6-glucan biosynthesis in fungal cell walls [55]. Other alkaloids extracted from Dichroa febrifuga leaves contain febrifugine that inhibit the zoospore release and germination of Phytophthora sp. [56].

A natural flavonoid found in licorice, liquiritin, could induce autophagy, apoptosis, and reduce the intracellular Ca2+ that inhibits the mycelial growth of P. capsici [57]. It also inhibits the expression of PcCRN4 and Pc76RTF virulence genes [57]. The PcCRN4 gene induces cell death in the host plant suppressing its expression could significantly reduce pathogen virulence [58]. Another flavonoid extracted from Mentha leaves also showed good antifungal ability against Phytophthora [59]. The high concentration of eriocitrin found in the Mentha leaf extract was believed to hold antimicrobial effect, though the mode of action still needs to be investigated [60].

A high concentration of citral, terpenoids found in lemongrass, affected the P. capsici growth and morphology, zoospore germination, and cell membrane permeability [61]. Citral works by affecting ERG6, inhibiting the ergosterol biosynthesis [62]. Ergosterol is a vital component in the fungal cell membrane that is responsible for its structure, fluidity, and permeability [63]. The defect in ergosterol biosynthesis not only deformed the hyphae but also limit its ability to interact with protein related pathogenicity [64].

3.2 Induced plant disease resistanceSome botanical fungicides can induce disease resistance in plants, enhancing their ability to withstand pathogen attacks. Proanthocyanidin and phenolic compounds extracted from the shell and husk of pecan (Carya illinoinensis) were proven to induce resistance of pepper plants towards P. capsici by leading to the production of salicylic acid [65]. Another beneficial plant-based fungicide is ginger essential oil, which significantly reduces the leaf necrosis due to the infection of P. colocasiae [66]. The ginger essential oil consisted of citral (95%) [66], a compound which able to enhance the plant resistance by inducing the activity of peroxidase, which holds an important role in cellular detoxification, wound healing, and phenolic compound oxidation [67]. Citral activated the systemic acquired resistance (SAR) in plants through the SA pathway by inducing the overexpression of genes related to salicylic acid (SA) biosynthesis.

Citral also induced the overexpression of defense enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) in tobacco as well as induced the overexpression of PR proteins, including NPR1, PR1, PR2, and PR5 [68]. SAR can also be activated by the accumulation of ROS [69]. Flavonoids extracted from Citrus reticulata, naringenin, induced the accumulation of reactive oxygen species in the host plant [70]. It also induced the expression of the basal pathogen resistance gene PR1 and the SAR8.2 gene that contributes to plant resistance to Phytophthora [71]. The difference botanical fungicide mode of action between direct antifungal properties and induced plant resistance was shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Aspect | Direct Antifungal Activity | Induced Plant Disease Resistant |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Direct inhibition of fungal pathogens through toxic effects on fungal cells. | Activation of the plant’s innate immune system to resist pathogen infection. |

| Primary Target | Pathogen (fungal cells, spores, or mycelia) | Host plant defense system |

| Mode of Action | Disrupts fungal cell walls and membranes. Inhibits key enzymes and biosynthetic pathways (e.g., β-1,6-glucan, ergosterol); Interferes with fungal metabolism, respiration, and virulent gene expression. | Triggers Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR) or Induced Systemic Resistance (ISR); Activates defense-related enzymes (POD, SOD, CAT, PAL); Induces PR proteins (NPR1, PR1, PR2, PR5); Stimulates salicylic acid (SA) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling |

| Representative Compounds | Alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, phenolics. | Flavonoids, terpenoids, phenolics, proanthocyanidins. |

| Main Biological Outcome | Fungal growth inhibition, spore germination suppression, hyphal deformation, and cell death. | Enhanced plant tolerance, faster defense response, reduced disease severity, and systemic immunity. |

| Typical Observation | Morphological damage to fungal hyphae observed under SEM; membrane collapse and cytoplasmic leakage. | Increased activity of defense-related enzymes and upregulation of resistance genes in treated plants. |

| Advantages | Rapid action; directly lethal to pathogens. | Provides long-term protection; less likely to cause pathogen resistance. |

| Limitations | Short persistence may require higher concentrations; possible phytotoxicity. | Slower onset; variable response depending on plant species and environmental conditions |

A meta-analysis study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of different plant-based pesticides against P. capsici. In total, 30 reports that were published between 2006 and 2023 were analyzed. Consisting of 80 studies that met the criteria and were included in the final database. The criteria such as inclusion of inhibitory data, laboratory condition research, and complete data provided.

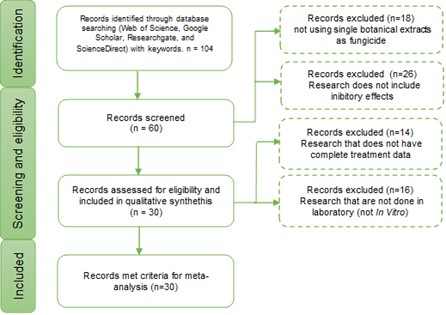

The data selection and literature search were conducted mainly in two stage: 1) Identification (to develop a database by digital literature search), 2) Screening (to filter out the literature and data that is eligible for meta-analysis). The first stage (identification) was carried out using Web of Science, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and ScienceDirect (Figure 2). The keywords used in this literature search were P. capsici, botanical fungicide for P. capsici, botanical extracts against P. capsici, Inhibitory effects P. capsici, and antifungal activity against P. capsici. Additional research was also carried out in the literature found in the first search to find more accurate information. A systematic review to develop a database (data selection) was conducted between November 2023 to July 2024. A total of 104 studies were evaluated and screened using criteria needed for meta-analysis.

The screening stage is mainly conducted using some criteria established to make an accurate analysis. Reports that did not use botanical extracts as pesticide were excluded. If the botanical extract was used as a mixed pesticide, the reports would be excluded as well. Reports that did not include inhibitory effects were eliminated, as the basis of the meta-analysis carried out was the antifungal activity of the pesticide against P. capsici. The literature whose research was carried out in non-laboratory conditions was also excluded, as the conditions would be too varied. The reports that did not provide complete data (ex, concentration, time of application, no repetition counts) were eliminated as it could not be used in Meta-Analysis. A total of 30 reports (published around 2006–2022) comprising of 80 studies met the criteria above and compiled as a final database were shown in Table 2.

| No | Plant name | Family | Botanical formulation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Uvularia grandiflora | Colchicaceae | Extract | [72] |

| 2 | Tetradium sp. | Rutaceae | Essential oil | [73] |

| 3 | Zanthoxylum armatum | Rutaceae | Essential oil | [73] |

| 4 | Gautieria sp. | Gomphaceae | Essential oil | [73] |

| 5 | Citrus medica | Citron | Essential oil | [73] |

| 6 | Berberus vulgaris | Berberidaceae | Extract | [74] |

| 7 | Tamarix tetranda | Tamaricaceae | Extract | [74] |

| 8 | Boerhavia difussa | Nyctaginaceae | Extract | [75] |

| 9 | Eupatorium adenophorum | Asteraceae | Extract | [76] |

| 10 | Inula britannica | Asteraceae | Esential oil | [77] |

| 11 | Allium sativum | Amaryllidaceae | Extract | [78] |

| 12 | Origanum vulgare | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 13 | Palmarosa | Poaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 14 | Thymus serpyllum | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 15 | Syzygium aromaticum | Myrtaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 16 | Cinnamomum verum | Lauraceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 17 | Cymbopogon nardus | Poaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 18 | Mentha piperita | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 19 | Mentha spicata | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 20 | Pimenta racemosa | Myrtaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 21 | Salvia lavandulifolia | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 22 | Foeniculum vulgare | neem | Essential oil | [79] |

| 23 | Melaleuca alternifolia | Myrtaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 24 | Rosmarinus officinalis | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 25 | Lavandula officinalis | Lamiaceae | Essential oil | [79] |

| 26 | Curcuma zedoaria | Zingiberaceae | Essential Oil | [80] |

| 27 | Yucca | Asparagaceae | extracted | [81] |

| 29 | Parthenium hysterohorus | Asteraceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 29 | Azadirachta indica | Meliaceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 30 | Calotropis gigantea | Apocynaceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 31 | Cassia fistula | Fabaceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 32 | Ocimum basilicum | Lamiaceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 33 | Nerium oleander | Apocynaceae | Extracted | [82] |

| 34 | Phyllostachys pubescens | Poaceae | Extracted | [83] |

| 35 | Cinnamomum verum | Lauraceae | Essential Oil | [84] |

| 36 | Diospyros nigra | Ebenaceae | Extracted | [84] |

| 37 | Azadirachta indica | Meliaceae | Essential Oil | [84] |

| 38 | Piper chaba | Piperaceae | Extract | [85] |

| 39 | Larrea tridentata | Zygophyllaceae | Extract | [86] |

| 40 | Silene armeria | Caryophyllaceae | Essential oil | [87] |

| 41 | Azadirachta indica | Meliaceae | Extract | [88] |

| 42 | Tridax procumbens | Asteraceae | Extract | [88] |

| 43 | Venonia amygdalina | Asteraceae | Extract | [88] |

| 44 | Larrea tridentata | Zygophyllaceae | Extract | [89] |

| 45 | Quercus pungens | Fagaceae | Extract | [89] |

| 46 | Flourensia cernua | Lycopodiaceae | Extract | [89] |

| 47 | Fragaria viridis | Rosaceae | Extract | [90] |

| 48 | Fragaria x ananassa | Rosaceae | Extract | [90] |

| 49 | oroxylum indicum | Bignoniaceae | Extract | [91] |

| 50 | Embelia ribes | Primulaceae | Extract | [91] |

| 51 | Celastrus paniculatus | Celastraceae | Extract | [91] |

| 52 | Saraca asoca | Fabaceae | Extract | [91] |

| 53 | Allamanda cathartica) | Apocynaceae | Extract | [92] |

| 54 | Areca catechu | Areceae | Extract | [93] |

| 55 | Uncaria gambir | Rubiaceae | Extract | [93] |

| 56 | Piper betle | Piperaceae | Extract | [93] |

| 57 | Allium sativum | Amaryllidaceae | Extract | [94] |

| 58 | Prunus mume | Rosaceae | Extract | [95] |

| 59 | Helianthus tuberosus | Asteraceae | Extract | [96] |

| 60 | Capsicum annuum | Solanaceae | Extract | [97] |

| 61 | Therminalia chebula | Combretaceae | Extract | [98] |

| 62 | Helianthus tuberosus | Asteraceae | Extract | [99] |

| 63 | Eucalyptus grandis | Myrtaceae | Nano emulsification | [100] |

| 64 | Jatropha curcas | Euphorbiaceae | Extract | [101] |

| 65 | Ageratum houstonianum | Asteraceae | Extract | [102] |

The efficacy of different botanical fungicide was calculated using Hedge’s g effect size model in the R environment. Hedge’s g is a standardized mean difference that has been adjusted for positive bias. This is calculated by dividing the raw mean difference by the pooled standard deviation of the two groups. Additionally, this metric works better than the log-response ratio for including values in our dataset that are zero or almost zero [103].

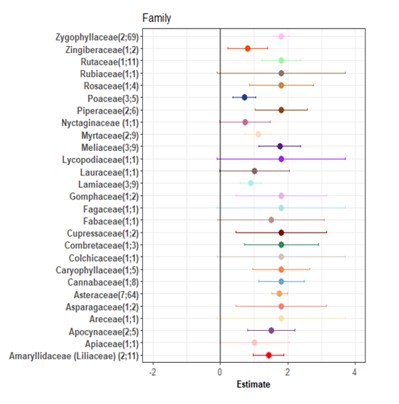

In this study, a forest plot was used to illustrate the estimated effects of various plant families on the response variable. From the diagram, it is evident that some plant families show strong positive estimates, suggesting a higher association or influence with the efficacy in controlling Phytophthora, while others display lower or even negative estimates (Figure 3). For example, Amaryllidaceae, Zygophyllaceae, and Apocynaceae distinctively positive, indicating the highest efficacy against fungal phytopathogens. Conversely, families like Nyctaginaceae, Lauraceae, and Apiaceae exhibits estimates that are closer to the null line (estimate = 0), suggesting no statistically significant effect or a more moderate influence.

Zygophyllaceae, including Larrea tridentata, exhibits antifungal activity primarily through its rich content of phenolic compounds, especially nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) [104]. NDGA exhibits antimicrobial activity by targeting the cell membrane [105]. L. tridentata extract also contain meso-dihydroguaiaretic acid, that reported to hold antifungal properties [106].

The Amaryllidaceae contain 3-vinyl-1,2-dithiacyclohex-5-ene and 3-vinyl-1,2-dithiacyclohex-4-ene as major active compounds. These compounds were causing a change in membrane permeability that led to the destruction of the structural integrity of cell membranes [107]. Allium sativum, a member of Amaryllidacea used in this study, contains allicin that is able to react with thiol groups in fungal enzymes and protein, causing enzyme inactivation as well as protein denaturation [108].

Calotropis procera, a member of Apocynaceae family, contains osmotin that could inhibit fungal spore germination [109]. The osmotin induced the membrane permeabilization of spores and hyphae [109]. Another member of the Apocynaceae family in this study is Nerium oleander. The plant extract investigation showed that it rich in alkaloids, tannins, flavonoids, steroids, and terpenoids [110]. This compound is well known for its antimicrobial activities.

The meta-analysis indicates that botanical fungicides derived from certain plant families could be promising candidates for controlling P. capsici. By harnessing these plant-based compounds, we could develop sustainable pest control strategies that not only target P. capsici but also reduce reliance on synthetic chemicals. Moreover, as botanical pesticides are often biodegradable and less toxic to non-target organisms, their use could improve biodiversity and support ecological balance within farming systems.

1. StandardizationDespite the promising results, the use of botanical fungicides faces several challenges:

2. Shelf LifeThe efficacy of botanical pesticides can vary depending on the source and preparation of the plant material, making standardization difficult. Challenges include the absence of Good Agricultural and Collection Practices (GACP), limited transparency within the raw material supply chain, and difficulties in the authentication of herbal raw materials, and a widespread lack of awareness regarding the importance of minimizing phytochemical variability in these materials [111]. As a result, it is difficult to standardize their use in applications like fungicides. For example, essential oil extracted from Alpina nigra cultivated in Kalimpong, India, primarily contained β-pinene, with myrtenol, alpha-humulene, and alpha-farnesene as secondary compounds [112]. Meanwhile, essential oil from A. nigra grown in Guwahati, India, had β-caryophyllene, β-pinene, and α-humulene as its main constituents [113]. Samples from the same species of plant grown in Northeast India have 1,8-cineole as its major compound [114].

Botanical pesticides often have a shorter shelf life compared to synthetic chemicals, limiting their practicality for large-scale use. Most chemical fungicides have an indicated shelf life, usually 2 years after the manufacture date. However, botanical fungicides, due to their natural attributes, usually decompose within days or even hours after the preparation and application. This natural biodegradation means that botanical fungicides’ residue, unlike its synthetic competitor, does not accumulate in plants. This natural biodegradation usually differs from one botanical fungicide to another, due to their different chemical composition and their natural attributes, so botanical fungicides might need more in-depth research to find the best formulations or storage methods to extend their shelf life.

Botanical fungicide represents a promising alternative to synthetic chemicals in the management of Phytophthora capsici in black pepper cultivation. Their efficacy, coupled with environmental and health benefits, makes them suitable candidates for inclusion in sustainable pest management strategies. However, further research and development are required to overcome existing challenges and ensure their widespread adoption by farmers.