2014 年 37 巻 6 号 p. 1062-1067

2014 年 37 巻 6 号 p. 1062-1067

Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is correlated with a reduced risk of cancer through the reduction of inflammation, which is an important risk factor. Several studies have investigated polymorphisms in the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) gene and NSAID use in association with cancer risk. However, these studies yielded mixed results. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the association of PPARγ polymorphisms and NSAID usage with cancer risk. We conducted a comprehensive search of PubMed through May 2013. Odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the fixed-effect or random-effect model. A comprehensive search of the database revealed 6 studies that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. NSAID use was significantly associated with decreased cancer risk regardless of PPARγ rs1801282 genotypes. In a stratified analysis by cancer type, NSAID users who were minor allele carriers had significantly decreased colon cancer risk compared to non-NSAID users (OR=0.73, 95% CI=0.57–0.93), whereas NSAID users homozygous for the major allele had significantly decreased risk for cancers other than colon cancer compared to non-NSAID users (OR=0.79, 95% CI=0.69–0.91). Our results suggest that the association of PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and NSAID use with the risk of cancer may differ according to cancer type.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), which exists as 3 isoforms, PPARγ1, PPARγ2, and PPARγ3, is a nuclear receptor that functions as a transcriptional regulator of metabolism. In the pathophysiology of obesity and insulin resistance, PPARγ is activated by binding to fatty acids, and it promotes the accumulation of adipose tissue. PPARγ agonists induce cell cycle arrest, differentiation, and apoptosis in adipose cells, which enhance insulin sensitivity.1) PPARγ also possesses anti-inflammatory properties.2,3) Activation of PPARγ inhibits the production of cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) by antagonizing the activities of the transcription factors activator protein 1 (AP1), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and nuclear factor-kappa-B (NF-κB), which inhibits induction of the inflammatory response.4–7)

Clinical and epidemiological studies suggest that chronic inflammation predisposes people to several types of cancer, including bladder, cervical, gastric, intestinal, esophageal, ovarian, prostate, and thyroid cancer. The connection between inflammation and cancer is mediated by several mechanisms that generate an inflammatory microenvironment.8,9) Studies suggest that PPARγ activation inhibits the proliferation of malignant cells from different lineages such as liposarcoma, breast adenocarcinoma, prostate carcinoma, colorectal carcinoma, non-small-cell lung carcinoma, pancreatic carcinoma, bladder cancer, and gastric carcinoma.10)

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce inflammation by decreasing the synthesis of prostaglandin (PG), and inhibiting NF-κB and PPARγ activation.11–13) NSAIDs are one of the most widely used medicines for the prevention and/or treatment of various diseases. From several epidemiological studies, it is suggested that NSAID use is correlated to a reduced risk of cancer; however, this is controversial. In addition, genetic variation in PPARγ has been postulated to be related to NSAID use with cancer risk. Although many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are located in the PPARγ region, to date, only the rs1801282 polymorphism (Pro12Ala) has been analyzed in several studies. The Pro12Ala mutation reduces the transcription of PPARγ2.3,14) Activation of PPARγ inhibits the production of inflammatory cytokines4–7) and the proliferation of malignant cells.10) NSAIDs reduce inflammation by activating PPARγ.11–13) Therefore, it is thought that the PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism influences cancer risk in conjunction with NSAID usage. However, the association studies between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and NSAID use with the risk of developing cancer yielded mixed results. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to solve the uncertainty of the association of PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphisms and NSAID use with the risk of developing cancer.

We searched for publications in MEDLINE, Science Direct, and the Cochrane Library using the keywords and strategy terms “peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma” or “PPAR gamma,” “NSAID,” “genotype” or “polymorphism,” and “cancer” or “carcinoma” (the last search was performed in May 2013). Non-controlled trials were excluded. Randomized controlled trials with 3 or more groups were retained if at least 2 groups addressed an eligible comparison. The cited references of articles retrieved after abstract review have been added as relevant studies.

Inclusion CriteriaStudies fulfilling the following criteria were included: (1) full-text articles written in English; (2) controlled trials comparing PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphisms and NSAID usage status with the risk of cancer; (3) sufficient published data for estimating odds ratio (OR) or relative risk with 95% confidence interval (CI); and (4) the number of cases, controls, NSAID users, and non-NSAID-users correlated to PPARγ rs1801282 genotypes. The following details were not considered for selection: (1) blinded nature of the trial, (2) type of cancer, (3) type of NSAID used, and (4) NSAID dosage method.

Data ExtractionData was independently extracted by 2 authors (Nagao and Sato) according to the inclusion criteria using a standard protocol. The following data were extracted: the name of the first author, year of publication, country where research institution was located, type of cancer, study design, age, gender, and the number of cases and controls with NSAID users or non-users by genotype.

Statistical AnalysisAll statistical analyses were performed using the rmeta package for R, version 2.14.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Tsukuba, Japan; http://www.R-project.org). Two-sided probability (p) values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. ORs with 95% CIs were calculated to assess the strength of the following associations: (1) PPARγ rs1801282 genotype of NSAID users and the risk of developing cancer, (2) NSAID use in individuals homozygous for the major allele and the risk of developing cancer, (3) the PPARγ rs1801282 genotype of non-NSAID users and the risk of developing cancer, and (4) NSAID use in individuals with the minor allele and the risk of developing cancer.

Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed by using the Pearson’s χ2 test for genotypes in the control group for each study. All meta-analyses were assessed for inter-study heterogeneity using χ2-based Q statistics for the statistical significance of heterogeneity. If there was no heterogeneity based on a Q-test p value of 0.05, a fixed-effect model using the Mantel–Haenszel (M-H) method was used. Otherwise, the random-effects model using the DerSimonian and Laird method was employed. Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the stability of the results by sequential omission of individual studies. To evaluate possible publication bias, Egger’s test (linear regression method) and Begg’s test (rank correlation method) were used, and p values of <0.05 were considered representative of statistically significant publication bias.

The search strategy retrieved 86 potentially relevant studies. According to the inclusion criteria, 6 studies with full-text were included in the meta-analysis.15–20) The flow chart of study selection is summarized in Fig. 1. The baseline characteristics and methodological quality of all included studies are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1. Six studies reported on the association between the PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and the risk of developing cancer in conjunction with NSAID usage. The genotypes of rs1801282 SNP was in HWE in the control of each study.

| Study | Country | Outcome | Study design | Age | Gender | Case | Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of non-user | No. of user | No. of non-user | No. of user | ||||||

| No. of males/females | CG+GG/CC | CG+GG/CC | CG+GG/CC | CG+GG/CC | |||||

| Pinheiro et al., 201015) | U.S.A. | OC | Case-control study | 32–69 | 0/3176 (females only) | 215/791 | 85/200 | 284/1012 | 132/357 |

| Vogel et al., 200816) | Denmark | LC | Nested case-cohort study | 50–64 | 631/516 | 65/211 | 36/87 | 136/372 | 62/167 |

| Vogel et al., 200717) | Denmark | BCC | Nested case-cohort study | 50–64 | 293/326 | 60/163 | 24/54 | 59/158 | 24/71 |

| Vogel et al., 200718) | Denmark | CRC | Nested case-cohort study | 50–64 | 618/490 | 67/173 | 33/77 | 137/375 | 64/170 |

| Vogel et al., 200719) | Denmark | BC | Nested case-cohort study | 50–64 | 0/712 (females only) | 41/115 | 35/165 | 34/100 | 68/154 |

| Slattery et al., 200620) | U.S.A. | CC | Case-control study | 30–79 | Without details | 216/755 | 125/476 | 252/756 | 225/734 |

CG+GG/CC indicate number of minor allele carriers (CG+GG)/individuals homozygous for the major allele (CC) of PPARγ rs1801282. Abbreviations: non-user, non-NSAID users; user, NSAID users; OC, ovarian cancer ; LC, lung cancer; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; CRC, colorectal cancer; BC, breast cancer; CC, colon cancer.

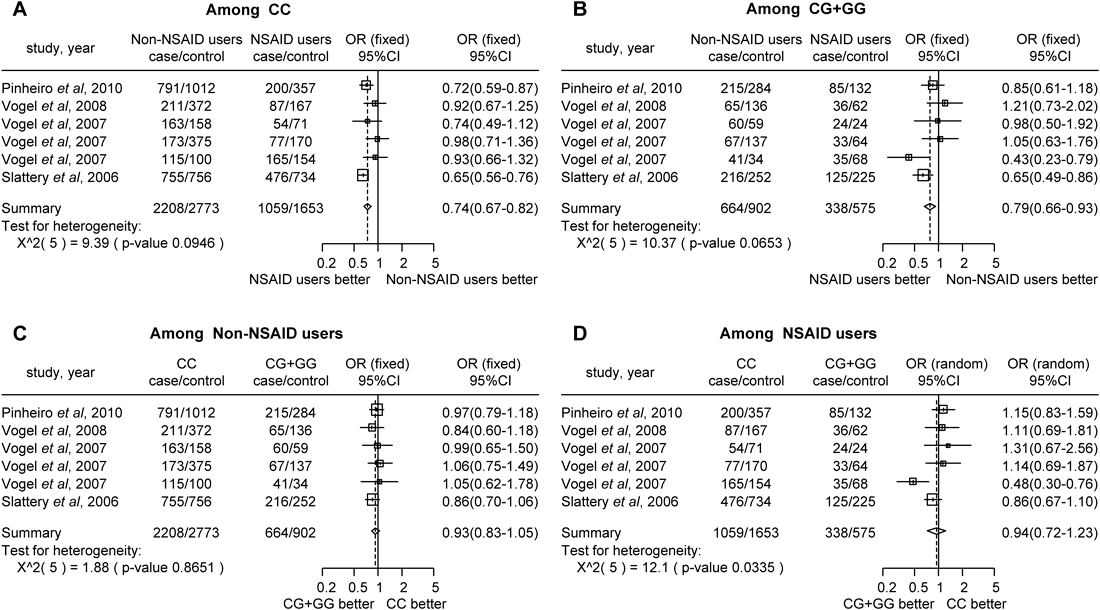

In the meta-analysis, there were significant differences in cancer incidence between NSAID users and non-NSAID users who were both homozygous for the major allele (CC) (Fig. 2A, OR=0.74, 95% CI 0.67–0.82) and minor allele carriers (CG+GG) of PPARγ rs1801282 (Fig. 2B, OR=0.79, 95% CI 0.66–0.93). However, there were no significant differences between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism (CC vs. CG+GG) and cancer risk in both non-NSAID (Fig. 2C, OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.83–1.05) and NSAID users (Fig. 2D, OR=0.94, 95% CI=0.72–1.23). Therefore, NSAID usage significantly decreased cancer risk compared with non-NSAID usage, regardless of the PPARγ rs1801282 genotype. There was significant heterogeneity between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and the risk of cancer in NSAID users (Fig. 2D, p=0.034). However, there was no significant heterogeneity between NSAID usage and the risk of cancer in individuals homozygous for the major allele (Fig. 2A, p=0.095), or minor allele carriers (Fig. 2B, p=0.065), or between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and the risk of cancer among non-NSAID users (Fig. 2C, p=0.865).

The difference in the risk of developing cancer between NSAID users and non-NSAID users among individuals homozygous for the major allele (CC) (A), between NSAID users and non-NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (CG+GG) (B), between non-NSAID users homozygous for the major allele and non-NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (C), and between NSAID users homozygous for the major allele and NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (D). Squares represent study-specific ORs; horizontal lines represent 95% CIs; the size of the square reflects study-specific statistical weight (inverse of the variance); diamonds represent summary OR and 95% CI; ORs (fixed) were analyzed with the fixed-effect model; ORs (random) were analyzed with the random-effect model. CC indicates individuals homozygous for the major allele, and CG+GG indicates the minor allele carriers.

In the stratified analysis by cancer type, there were no significant differences in the risk of developing colon cancer between NSAID users and non-NSAID users homozygous for the major allele (Fig. 3A, OR=0.78, 95% CI=0.52–1.16); however, among minor allele carriers, NSAID users had a significantly lower colon cancer risk than non-NSAID users (Fig. 3B, OR=0.73, 95% CI=0.57–0.93). For cancers other than colon cancer, NSAID users who were homozygous for the major allele had significantly lower cancer risk than non-NSAID users (Fig. 3A, OR=0.79, 95% CI=0.69–0.91). In contrast, there was no significant difference in cancer risk between NSAID users and non-NSAID users who were minor allele carriers (Fig. 3B, OR=0.84, 95% CI=0.67–1.06). Regardless of the cancer type, there was no significant difference between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism (CC vs. CG+GG) and the risk of cancer in both non-NSAID (Fig. 3C) and NSAID users (Fig. 3D). In the subgroup analysis by location, there were no associations among the people of Denmark (Figs. 4A–D). In the U.S.A., NSAID usage in individuals homozygous for the major allele significantly decreased cancer risk compared with non-NSAID usage (Fig. 4A, OR=0.67, 95% CI=0.60–0.76). Similarly, NSAID usage significantly decreased cancer risk compared with non-NSAID usage in minor allele carriers (Fig. 4B, OR=0.73, 95% CI=0.59–0.90). However, there was no significant difference between PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism (CC vs. CG+GG) and the risk of cancer in both non-NSAID (Fig. 4C) and NSAID users (Fig. 4D). Therefore, the risk of developing cancer was not associated with NSAID usage and the PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism in Denmark and the U.S.A.

The difference in the risk of developing cancer between NSAID users and non-NSAID users among individuals homozygous for the major allele (CC) (A), between NSAID users and non-NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (CG+GG) (B), between non-NSAID users homozygous for the major allele and non-NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (C), and between NSAID users homozygous for the major allele and NSAID users who are minor allele carriers (D). Squares represent study-specific ORs; horizontal lines represent 95% CIs; the size of the square reflects study-specific statistical weight (inverse of the variance); diamonds represent summary OR and 95% CI; ORs (fixed) were analyzed with the fixed-effect model; ORs (random) were analyzed with the random-effect model. CC indicates individuals homozygous for the major allele, and CG+GG indicates the minor allele carriers.

The difference in the risk of development of cancer between NSAID users and non-NSAID users among homozygous for the major allele (CC) (A), between NSAID users and non-NSAID users among minor allele carriers (CG+GG) (B), between homozygous for the major allele and the minor allele carriers among non-NSAID users (C), and between homozygous for the major allele and the minor allele carriers among NSAID users (D). Squares represent study-specific ORs; horizontal lines represent 95% CIs; the size of the squares reflects study-specific statistical weight (inverse of the variance); diamonds represent summary OR and 95% CI; ORs (fixed) were analyzed with the fixed-effect model; ORs (random) were analyzed with the random-effect model. CC indicates individuals homozygous for the major allele, and CG+GG indicates the minor allele carriers.

Sensitivity analysis indicated that the independent study by Slattery et al.20) was primarily responsible for the association between NSAID usage and the risk of cancer in minor allele carriers in the overall group. Sensitivity analysis for cancers other than colon cancer indicated that the independent study by Pinheiro et al.15) was primarily responsible for the association between NSAID usage and the risk of cancer in individuals homozygous for the major allele. These results suggested that the existing between-study heterogeneity and the limited number of studies might have influenced the ORs. Publication bias was accessed by Begg’s test and Egger’s test (Table 2). Begg’s test did not suggest any evidence for potential publication bias. Meanwhile, Egger’s test indicated that publication biases might not have a significant effect on the results of the overall analysis except for the association between NSAID usage and homozygosity for the PPARγ rs1801282 major allele (p=0.044).

| PPARγ rs1801282 | Non-user vs. User (CC) | Non-user vs. User (CG+GG) | CC vs. CG+GG (Non-user) | CC vs. CG+GG (User) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | 0.044 | 0.633 | 0.435 | 0.781 |

| PB | 0.348 | 0.851 | 0.573 | 0.348 |

Abbreviations: Non-user, non-NSAID user; User, NSAID user; CC, individuals homozygous for the major allele of PPARγ rs1801282; CG+GG, minor allele carriers of PPARγ rs1801282; PE: P for Egger’s test, PB; P for Begg’s test. The value (in boldface) indicates potential population bias.

In the current study, we performed a meta-analysis to determine the association of PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphisms and NSAID usage with the risk of developing cancer. However, the results of our meta-analysis indicated that NSAID usage significantly decreased the cancer risk regardless of the PPARγ rs1801282 genotype. However, we found that the association of PPARγ rs1801282 genotype and NSAID usage with cancer risk differed according to cancer type. Our meta-analysis showed that NSAID intake among minor allele carriers decreased the risk of developing colon cancer, whereas NSAID intake among individuals homozygous for the major allele decreased the risk of cancers other than colon cancer. The discrepancy in our meta-analysis may be partially explained by the association between diabetes and colon cancer. There is an association between increased risk of colon cancer and diabetes (primarily type 2).21) Possible mechanisms for a direct link between diabetes and cancer include hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and inflammation. The lower transactivation capacity of the Ala variant of PPARγ2 is a potential molecular mechanism underlying the association of this allele with lower BMI and higher insulin sensitivity.3) Two large population-based studies from Finland and Japan suggested that the Ala variant of PPARγ2 is associated with a reduced risk of type 2 diabetes.22,23) One meta-analysis observed that the Ala allele of the PPARγ gene was associated with a reduced risk of colon and rectal cancer.24) Therefore, because minor allele carriers have lower levels of PPARγ transcript than homozygous individuals, NSAID intake further reduces the expression of PPARγ, and decreases the risk of developing colon cancer via the mechanism described above.

In the stratified analysis by location, we found that there was no association of NSAID intake with cancer risk and PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism in Denmark and the U.S.A.; however, further studies with larger sample sizes, including other populations, are required to establish any difference in ethnicity.

In conclusion, our results did not indicate a significant association of the PPARγ rs1801282 polymorphism and NSAID intake with the risk of developing cancer. However, our results suggest that the association of this polymorphism and NSAID intake with the risk of cancer may differ by cancer type.