2016 年 39 巻 9 号 p. 1482-1487

2016 年 39 巻 9 号 p. 1482-1487

It is thought that eating habits induces individual variation in intestinal absorption and metabolism of drugs. The objective of this research was to clarify the influence of vegetables juices on CYP3A4 activity, which is an important enzyme in intestine. Five vegetables juices (VJ-o, Kagome Original®; VJ-g, Kagome 30 kinds of vegetables and fruits®; VJ-p, Kagome Purple vegetables®; VJ-r, Kagome Sweet Tomato®; and VJ-y, Kagome Fruity Salada®; KAGOME Co., Ltd., Aichi, Japan) were centrifuged (1630×g, 10 min) and filtered using filter paper and 0.45-µm membrane filters. In this study, recombinant CYP3A4 and LS180 cells were used for the evaluation of CYP3A4 activity. The metabolisms to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by recombinant CYP3A4 were significantly inhibited by VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y in a preincubation time-dependent manner, and CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells were significantly inhibited by VJ-o and VJ-y. These results show that the difference in ingestion volume of vegetable juices and vegetables might partially induce individual difference in intestinal drug metabolism.

Congenital factors, such as genetic polymorphisms, and acquired factors, such as eating habit, induce individual variation in intestinal drug absorption and drug metabolism, so it is known that human intestinal absorption and metabolism of drugs varies widely among individuals. The genetic polymorphism of CYP3A5 is an important factor of the intestinal absorption, but that of CYP3A4 is not known. Therefore, the difference of eating habits might be an important for the individual variation of CYP3A4 activity.

Flavonoids, which are contained in various vegetables and fruits,1,2) have a wide range of bioactivities, including anti-oxidative and anti-tumor effects.3,4) Moreover, clinical studies have demonstrated that many flavonoid-containing beverages increase intestinal absorption of CYP3A4 substrates. For example, lime juice and grapefruit juice (GFJ) increase intestinal absorption of felodipine and nisoldipine, respectively.5,6) Because furanocoumarins contained in lime and grapefruit juices inhibit CYP3A4 activity in an irreversible manner, CYP3A4 activity may not recover for more than 3 d after drinking these juices.7,8) In addition, it has been reported that the flavonoid quercetin inhibits CYP3A4 activity in Caco-2 cells,9) and we have reported that various flavonoids inhibit CYP3A4 activity in human microsomes.10) These reports indicate that differences in daily intake of flavonoid-containing foods and beverages may induce individual variation in intestinal drug absorption.

Vegetables juices (VJs) are popular in Japan, where many people have a habit of drinking VJs every day to maintain good health. Several types of vegetables and fruit are used to make VJs (Table 1), which contain many types of flavonoids and may therefore inhibit CYP3A4 activity. The purpose of this study was to assess the effects of VJs on CYP3A4 activity using recombinant CYP3A4 and LS180 cells.

| Category | Materials | VJ-o | VJ-g | VJ-p | VJ-r | VJ-y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetable | Angelica keiskei | ● | ● | |||

| Asparagus | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Beet | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Bell pepper | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Broccoli | ● | ● | ||||

| Brussels sprouts | ● | ● | ||||

| Burdock | ● | |||||

| Cabbage | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Carrot | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Celery | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Chinese cabbage | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Corn | ● | |||||

| Eggplant | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Green peas | ● | |||||

| Japanese radish | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Jew’s mallow | ● | |||||

| Kale | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Komatsuna | ● | ● | ||||

| Lettuce | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Onion | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Parsley | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Pumpkin | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Purple potato | ● | |||||

| Red dell pepper | ● | |||||

| Red perilla | ● | ● | ● | |||

| Spinach | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Tomato | ● | |||||

| Violet cabbage | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| Watercress | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Fruit | Acerola | ● | ● | |||

| Apple | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Banana | ● | ● | ||||

| Black currant | ● | |||||

| Blueberry | ● | |||||

| Camu camu | ● | |||||

| Cranberry | ● | ● | ||||

| Grape | ● | ● | ||||

| Lemon | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Lime | ● | |||||

| Mango | ● | |||||

| Orange | ● | |||||

| Passion fruit | ● | ● | ||||

| Pineapple | ● | |||||

| Pomegranate | ● | |||||

| Prune | ● | |||||

| Raspberry | ● | ● |

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PDH), testosterone, and carbamazepine were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan). Human CYP3A4+P450 Reductase+Cytochrome b5 SUPERSOMES™ were purchased from BD Biosciences (Woburn, MA, U.S.A.). 6β-Hydroxytestosterone was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.). All other chemicals were reagent- or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)-grade commercial products.

VJs (VJ-o, Kagome vegetable life 100 original®; VJ-g, Kagome vegetable life 100 30 kinds of vegetables and fruits®; VJ-p, Kagome vegetable life 100 Purple vegetables®; VJ-r, Kagome vegetable life 100 Sweet Tomato®; and VJ-y, Kagome vegetable life 100 Fruity Salada®) were purchased from KAGOME Co., Ltd. (Aichi, Japan). GFJ (Dole® grapefruit 100%) was purchased MEGMILK SNOW BRAND Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). All juices were centrifuged (1630×g, 10 min) and filtered using filter paper and 0.45-µm membrane filters (Merck Millipore Co., Germany). Following removal of insoluble material by filtration, the juice samples were considered to consist of 100% juice. All VJs used in this study and their constituent vegetables and fruits are listed in Table 1. VJ-o was juice made from carrot, bell pepper, apple, orange, and so on (Table 1). VJ-g, VJ-p, VJ-r, and VJ-y included specific vegetables. Specifically, VJ-g included burdock, green peas, and lime; VJ-p included purple potato, red bell pepper, black currant, blueberry, pomegranate, and prune; VJ-r included tomato, and VJ-y included corn, camu camu, mango, and pineapple.

Detection of Recombinant Human CYP3A4 ActivityHuman CYP3A4 inhibition experiments were performed following a method reported by Nishikawa et al.11) and Patki et al.12) with slight modifications. Each reaction mixture contained 0.6 mM NADP, 6 mM G6P, 2 units/mL G6PDH, a test compound (GFJ (positive control), VJ-o, VJ-g, VJ-p, VJ-r, or VJ-y), and 5–200 µM testosterone (TST) in 0.2 M phosphate buffer with 10 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4). The reaction mixture was incubated at 37°C for 5 min, followed by initiation of the reaction by the addition of 7 pmol/mL of P450 to the human CYP3A4 reaction mixture. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min, followed by termination of the reaction by the addition of 50 µL of 5 M phosphoric acid.

The pre-incubation time-dependent experiments were performed using the methods described above with slight modifications. Each reaction mixture contained 0.6 mM NADP, 6 mM G6P, 2 units/mL G6PDH, a test compound (GFJ (positive control), 10% VJ-o, 10% VJ-g, or 10% VJ-y), and 3 pmol/mL human CYP3A4 and was pre-incubated at 37°C for 2, 4, or 6 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the reaction mixture (20 µL) to 280 µL of 10 µM testosterone in 0.2 M phosphate buffer with 10 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4). The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, followed by termination of the reaction by the addition of 50 µL of 5 M phosphoric acid.

The 6β-hydroxytestosterone assay was conducted using the HPLC-UV method reported by Nishikawa et al.11) with slight modifications. One milliliter of 1 M NaOH, 60 ng of carbamazepine as an internal standard, 350 µL of methanol, 1 mL of ultra-pure water, and 5 mL of toluene were added to 350 µL of the sample, and the mixture was shaken at 300 cycles/min for 10 min. After centrifugation at 1630×g for 20 min, the upper layer of the mixture was collected and evaporated to dryness at 65°C under a stream of N2. The residue was dissolved in the HPLC mobile phase (50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0)–methanol–acetonitrile=50 : 46 : 4), the upper layer was injected into the HPLC column, and the absorbance was measured at 245 nm with a UV detector (SPD-10A, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The HPLC apparatus and conditions were as follows: auto injector, Shimadzu SIL-10A; pump, Shimadzu LC-10AD; column, Inertsil ODS III (5 µm, 250 mm×4.0 mm i.d.); column temperature, 40°C; and flow rate, 1.0 mL/min. The calibration curves for 6β-hydroxytestosterone (0.25–4.0 µM) showed good linearity (R2>0.999).

Detection of CYP3A4 Activity in LS180 Cells Using the P450-Glo™ KitHuman colon adenocarcinoma LS180 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, U.S.A.) were selected for in vitro evaluation of CYP3A4 activity. CYP3A4 activity was measured using the P450-Glo™ assay (Luciferin-IPA: Promega, Madison, WI, U.S.A.) as reported by Cali et al.13) with slight modifications. Luciferin-IPA selectively reacted with CYP3A4, and hardly reacted with CYP3A5 and CYP3A7. LS180 cells were seeded in 24-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, U.S.A.) at 1×105 cells/mL and incubated with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for 4 d. The cells were then treated using luciferin-IPA with or without test juices (10% GFJ [positive control], 10% VJ-o, 10% VJ-g, or 10% VJ-y) for 4 h under shade. The reaction solutions (100 µL) were transferred to a 96-well opaque white luminometer plate, and 100 µL of luciferin detection reagent was added. Luminescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader (GENios, Tecan, Seestrasse, Switzerland). The CellQuanti-Blue™ test (BioAssay Systems, Hayward, CA, U.S.A.) was used to correct for cell amounts and the signal was quantified using a microplate reader (GENios; excitation wavelength, 535 nm; emission wavelength, 590 nm).

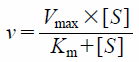

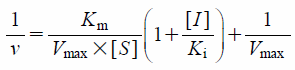

Estimation of Pharmacokinetic ParametersTo calculate the pharmacokinetic parameters (Michaelis constant (Km), maximum velocity (Vmax), and inhibition constant (Ki)) of testosterone metabolism by human recombinant CYP3A4, the following Eqs. 1 and 2 were fitted to the observed data by non-linear least-squares regression analysis with the MULTI program14):

| (1) |

| (2) |

All data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean. The significance of differences between means were determined using Student’s t-test or ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test. p-Values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

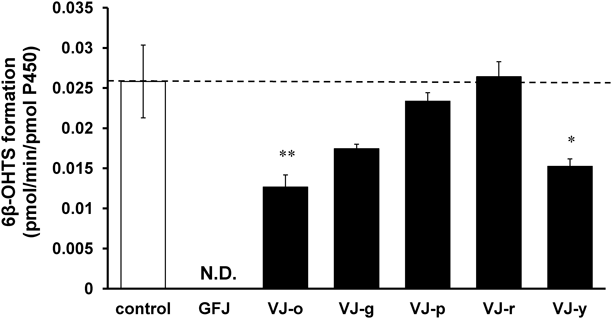

VJ-o and VJ-y significantly inhibited the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4, and VJ-g showed a non-significant tendency to inhibit the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4. VJ-p and VJ-r did not inhibit the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4 (Fig. 1).

The reaction was performed in an NADPH-generating system (final volume of 300 µL) containing human recombinant CYP3A4 (3 pmol/min/pmol P450) and testosterone (10 µM) at 37°C for 10 min after a pre-incubation for 5 min in the absence (control) or presence of 10% vegetable juice or grapefruit juice. Grapefruit juice (10%) was used as a positive control. Each column represents the mean±S.E.M. (n=3 or 4). The significance of the differences between the mean values was determined by Dunnett’s test (* p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 vs. control). N.D.: not detected.

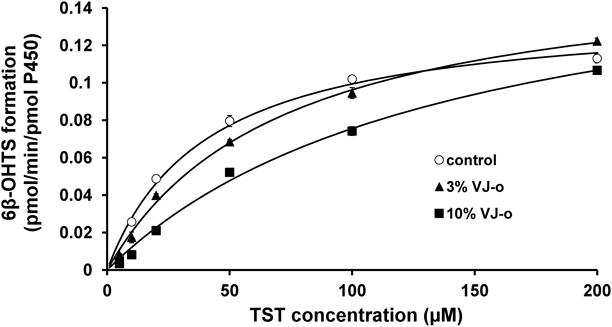

The Km values of the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone in the presence of 3 and 10% VJ-o were 71.3±6.1 and 140.5±17.3 µM, respectively, and these values were higher than that in the absence of VJ-o (40.1±3.1 µM) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). In addition, the Vmax values of the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone in the presence of 3 and 10% VJ-o were 0.17±0.006 and 0.18±0.012 pmol·min−1·pmol P450−1, respectively, and these values were equal to that in the absence of VJ-o (0.14±0.004 pmol·min−1·pmol P450−1) (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Furthermore, the Km values of the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone in the presence of 10% VJ-g and 10% VJ-y were 2.52- and 2.90-fold of that in the absence of VJ, respectively, but the Km values of the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone in the presence of 10% VJ-p and 10% VJ-r were equal to that in the absence of VJ. The tested VJs did not change the Vmax value of the metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4 (Fig. 3).

The reaction was performed in an NADPH-generating system (final volume of 300 µL) containing human recombinant CYP3A4 (3 pmol/min/pmol P450) and testosterone (5, 10, 20, 50, 100, or 200 µM) at 37°C for 10 min after a pre-incubation for 5 min in the absence (control: open circle) or presence of vegetable juice VJ-o (3%: closed triangle; 10%: closed square). Each point represents the mean±S.E.M. (n=4).

| Km (µM) | Vmax (pmol/min/pmol P450) | Vmax/Km (µL/pmol/min/P450) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 40.1±3.1 | 0.14±0.004 | 3.47 |

| 3% VJ-o | 71.3±6.1 | 0.17±0.006 | 2.31 |

| 10% VJ-o | 140.5±17.3 | 0.18±0.012 | 1.29 |

The values of Km and Vmax for the metabolism to 6β-OHTS were determined using human recombinant CYP3A4. Km and Vmax values were caluculated from the Michaeris–Menten kinetics. Each value represents the mean±S.D. (n=4).

The reaction was performed in an NADPH-generating system (final volume of 300 µL) containing human recombinant CYP3A4 (3 pmol/min/pmol P450) and testosterone (5, 10, 20, 50, 100, or 200 µM) at 37°C for 10 min after a pre-incubation for 5 min in the presence of the tested vegetable juices (10%). Changes in Km (A) and Vmax (B) changes were calculated using Michaelis–Menten kinetics. Each bar represents a 95% confidence interval.

The inhibitory constants (Ki values) of VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y were 2.93±0.56, 9.88±3.09, and 3.64±0.57%, respectively (Fig. 4). In addition, 10% VJ-o, 10% VJ-g, and 10% VJ-y significantly inhibited CYP3A4 activity in a manner similar to GFJ in a preincubation time-dependent manner (Fig. 5).

The reaction was performed in an NADPH-generating system (final volume of 300 µL) containing human recombinant CYP3A4 (3 pmol/min/pmol P450), and testosterone (circle: 5 µM; triangle: 20 µM; square: 100 µM) at 37°C for 10 min after a pre-incubation for 5 min in the presence of VJ-o (A), VJ-g (B), and VJ-y (C) (3, 5, 10, and 15%). Each point represents the mean±S.E.M. (n=4).

Grapefruit juice (A), VJ-o (B), VJ-g (C), and VJ-y (D) (all at 10%) were pre-incubated in an NADPH-generating system containing human recombinant CYP3A4 (final concentration of 3 pmol/min/pmol P450). Aliquots were removed from the pre-incubation mixtures at 2, 4, and 6 min and diluted 15-fold for measurement of residual CYP3A4 activity. The reaction was performed at 37°C for 10 min in a final volume of 300 µL containing 10 µM testosterone. Grapefruit juice (10%) was used as a positive control. Each column represents the mean±S.E.M. (n=5 or 6). The significance of the differences between the mean values was determined by unpaired Student’s t-test (* p<0.05 and ** p<0.01 vs. control).

VJ-o and VJ-y significantly inhibited CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells, and VJ-g slightly activated CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells (Fig. 6).

LS180 cells were incubated with Luciferin-IPA (3 µM) for 4 h in the absence (control) or presence of 10% vegetable juices. Luciferin detection reagent was added and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Grapefruit juice (10%) was used as a positive control. Each column represents the mean±S.E.M. (n=6). The significance of the differences between the mean values was determined by Dunnett’s test (** p<0.01 vs. control).

VJ-o and VJ-y significantly inhibited metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4, but VJ-p and VJ-r did not (Fig. 1). These results show that some VJs can inhibit CYP3A4 activity. Moreover, we demonstrated that the inhibitory effects of VJs depend on the types and relative proportions of their constituent vegetables and/or fruits.

The metabolic clearance (Vmax/Km) to 6β-hydroxytestosterone was decreased by VJ-o in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2, Table 1), while 10% VJ-o, 10% VJ-g, and 10% VJ-y increased its Km value by 2.5–3.5 times (Fig. 3A), but changed its Vmax only slightly (Fig. 3B). These results suggest that VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y competitively inhibit the activity of CYP3A4.

Bell pepper (Capsicum annuum) and onion (Allium cepa) were not constituents of VJ-p and VJ-r, which did not inhibit CYP3A4 activity, but they were constituents of VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y, which inhibited CYP3A4 activity (Table 1). Bell pepper and onion contain quercetin and kaempferol, which can inhibit CYP3A4 activity.9,10) Therefore, our results suggest that inhibition of CYP3A4 by some VJs is partly owing to the presence of quercetin and kaempferol from bell pepper and onion. Further studies are needed to identify the vegetables, fruits, and compounds that strongly inhibit CYP3A4.

The metabolism to 6β-hydroxytestosterone by human CYP3A4 was inhibited in a preincubation time-dependent manner by VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y (Fig. 5). Some fulanocumarins present in GFJ can inhibit CYP3A4 in an irreversible manner by bonding covalently with the heme iron in CYP3A4.8) Therefore, some VJs may also inhibit CYP3A4 in an irreversible manner by the same mechanism as grapefruit juice.

Importantly, the inhibitory constants (Ki values) of VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y ranged from 3–10% (Fig. 4), and 10% VJ-o and 10% VJ-y inhibited CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells (Fig. 6). These results suggest that ingestion of VJs can inhibit intestinal absorption of CYP3A4 substrates when the concentration of vegetable juice reaches 10%. VJ concentrations of in the gastrointestinal tract after VJ ingestion have not been studied directly, but these concentrations may be greater than 10% following ingestion of 200–300 mL juice, because the gastrointestinal volume is at most about 2 L. Taken together, our results demonstrate that ingestion of some VJs can increase the bioavailability of some drugs, which is further supported by the report that quercetin pretreatment increases the bioavailability of pioglitazone in rats.15)

VJ-g did not inhibit CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells (Fig. 6), suggesting that the inhibitory compounds present in 10% VJ-g could not penetrate the cell membrane. Indeed, VJ-g activated CYP3A4 activity in LS180 cells (Fig. 6), suggesting that compound(s) in VJ-g that were not present in the other VJs might have penetrated the cell membrane and activated CYP3A4, but further research is required to assess this possibility.

VJ-p and VJ-r did not inhibit CYP3A4 activity in this study (Fig. 1). It was reported, however, that cranberry and raspberry, which are present in VJ-p and VJ-r, can inhibit CYP3A4 activity.16) Therefore, these results suggest that VJ-p and VJ-r did not have sufficient volume or concentration of cranberry or raspberry to inhibit CYP3A4 activity.

In this study, we showed that VJ-o, VJ-g, and VJ-y inhibited CYP3A4 activity in a competitive and irreversible manner, and vegetable juices for the concentration, which is also considered in clinical situation, can inhibit CYP3A4 activity. Because of the distinct inhibitory effects on CYP enzymes of the various vegetables and fruits contained in the wide range of available VJs, individual differences in intestinal drug absorption might be induced by differences in preferences for particular VJs, fruits, and vegetables.

This study was supported financially in part by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan—Supported Program for the Strategic Research Foundation at Private Universities, 2012–2016 (S1201008).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.