2020 年 43 巻 12 号 p. 1831-1838

2020 年 43 巻 12 号 p. 1831-1838

Hemorrhoids are a common anorectal disease. Epidemiological studies on medication trends and risk factors using information from real-world databases are rare. Our objective was to analyze the relationship between hemorrhoid treatment prescription trends and several risk factors using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) Open Data Japan and related medical information datasets. We calculated the standardized prescription ratio (SPR) based on the 2nd NDB Open Data Japan from 2015. The correlation coefficients between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and those of “antispasmodics,” “antiarrhythmic agents,” “antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators,” “purgatives and clysters,” “hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics,” “psychotropic agents,” and “opium alkaloids preparations” were 0.7474, 0.7366, 0.7184, 0.6501, 0.6320, 0.4571, and 0.4542, respectively. The correlation coefficient between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and those of “average annual temperature,” “percentage of people who were smokers,” and “percentage of people who drank regularly” were −0.7204, 0.6002, and 0.3537, respectively. The results of cluster analysis revealed that Hokkaido and Tohoku regions tended to have low average annual temperature values and high percentage of people who were smokers and had comparatively high SPRs of “antispasmodics,” “antiarrhythmic agents,” “antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators,” “purgatives and clysters,” “hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics,” “psychotropic agents,” and “opium alkaloids preparations.” Antihemorrhoidals are frequently used in Hokkaido and Tohoku, Japan; thus, it is important for these prefectural governments to focus on these factors when taking measures regarding health promotion.

As the most common anal disease, hemorrhoids are characterized by the symptomatic enlargement and distal displacement of the anal cushions,1–3) via projections of anal mucosa formed by loose connective tissues, smooth muscle, and arterial and venous vessels.4) Hemorrhoids are commonly asymptomatic but can be complicated by painless bleeding, prolapse, soiling, and pruritus ani.5) Symptomatic hemorrhoidal disease is one of the most prevalent ailments associated with a significant effect on a patient’s QOL.6)

The risk factors for the development of hemorrhoids include aging, constipation, obesity, abdominal obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, depressive mood, and pregnancy.7–9) Some types of food and lifestyles, including smoking, alcohol intake, low fiber diet, and spicy foods, are suspected to be associated with the development of hemorrhoids and the aggravation of acute hemorrhoidal symptoms.8,10,11) Constipation is suspected to be associated with hemorrhoids. Therefore, the relationship between the use of purgatives and clysters for the treatment of constipation and hemorrhoids was examined.12,13) Anticholinergic agents that possess a high affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors are also known to cause constipation.14) Several drugs have been implicated in the development of constipation.12,13) Furthermore, the everyday lifestyle guidance provided to patients includes taking precautions when working at cold temperatures. The patients are instructed to avoid letting their bodies get too cold.1,15) However, the data are inconsistent, and these factors have not been well investigated.

The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) has been conducting the “Comprehensive Survey of Living Conditions (CSLC)” every year since 1986 based on the “Statistics Law.”16) The CSLC was conducted with approximately 277000 households from across the country in 2016.16,17) The purpose of the survey is to understand the actual living conditions of the participants and use basic statistical methods to draw conclusions for the population in Japan. The CSLC provides results such as family composition, health status, income status, employment situation, and nursing care status. Furthermore, the MHLW conducts other official statistical surveys, such as “Vital Statistics (VS)” and “National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan (NHNS).” All medical information datasets from National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB) Open Data Japan, CSLC, VS, and NHNS are open for public use and can be obtained from the MHLW and e-Stat websites.18)

Various large-scale medical information databases have been used for clinical and epidemiological research in Japan.19,20) In 2009, the MHLW developed the NDB, which covers over 95% of current insurance claim information provided by health insurance in Japan.21,22) The NDB contains data that has been prepared to optimize medical expenses. However, as the NDB contains most of the available data in the national healthcare insurance system and reflects the trends in medical care in Japan, it can be used to inform government policy and clinical research. Recently, the MHLW released the “NDB Open Data Japan (NODJ)” online; it provides various summary tables from the NDB that are freely available for use by the general public.

Compared to the data obtained by sampling survey, NDB data comprise a comprehensive dataset from individuals who have received a specific health checkup in Japan. As the survey covers the entire country, it is considered suitable for grasping the situation in each prefecture.23) Because NODJ is open data, it has only a few labor, cost, and ethical constraints, and research using it can be conducted in a relatively short time. To the best of our knowledge, hemorrhoid surveillance using NODJ has not been performed. Therefore, our objective was to analyze the relationship between hemorrhoids treatment prescription trends based on the standardized prescription ratio (SPR)24) using the population of each prefecture and several risk factors using NODJ and related databases.

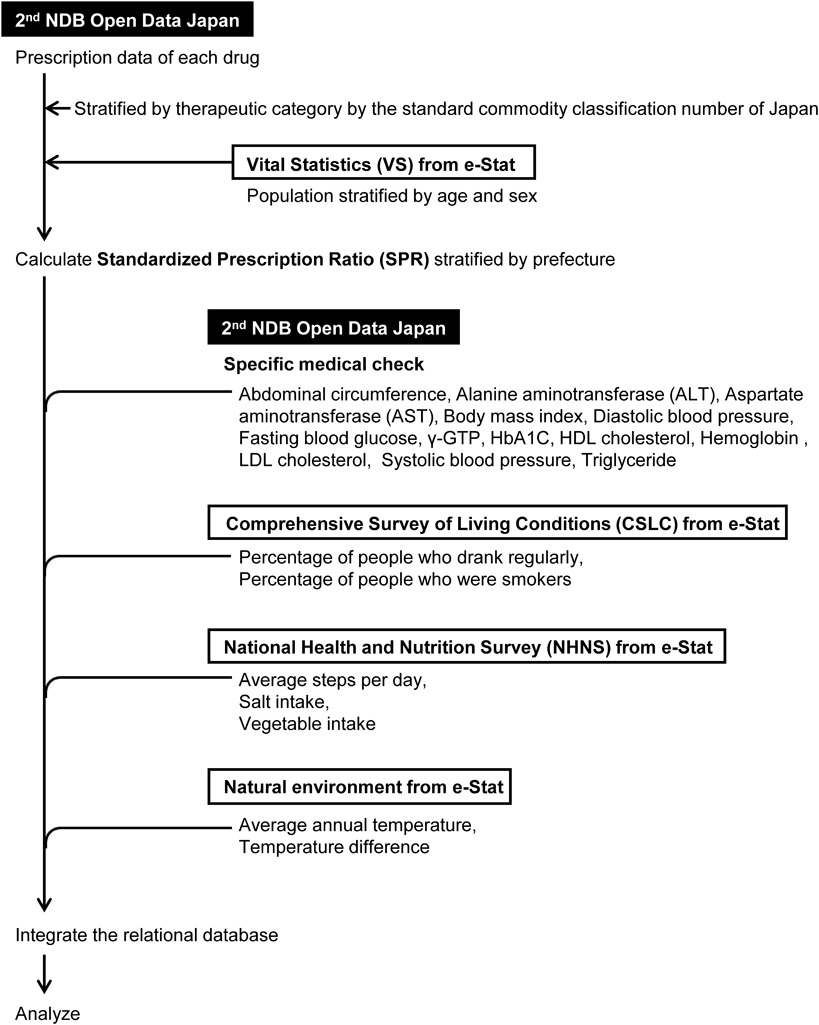

The NDB is based on claims from outpatients, inpatients, diagnosis procedure combinations, prescriptions, dental treatments, and specific checkup data.21) We obtained data from the MHLW website for NODJ25) and the e-Stat website for VS, CSLC, and NHNS (Fig. 1). We extracted data on drug usage (prescription) and specific medical checks [abdominal circumference, body mass index (BMI), etc.] from the second NODJ from 2015. In this study, we summed up the number of prescription drugs (internal/external/injection, outpatient/hospitalization, out-of-hospital prescription/hospital prescription) using the data tables (0000177287.xls, 0000177288.xls, 0000177289.xls, 0000177290.xls, 0000177291.xls, 0000177292xls, 0000177293.xls, 0000177294.xls, 0000177296.xls, and 0000177297.xls) from the MHLW website for NODJ.25) The percentage of individuals who were smokers and percentage of individuals who drank regularly were obtained from the CSLC in 2016.26,27) A person was defined as a smoker based on the following two criteria: “smoking every day” and “occasional smoking.” A person who drinks more than 3 d a week was defined as “people who drank regularly.” The average steps per day, salt intake, and vegetable intake were obtained from the NHNS in 2016.28) The average annual temperature was obtained from “natural environment” of e-Stat,29) and the temperature difference was calculated as the difference between the highest temperature (highest monthly average of daily maximum temperature) and lowest temperature (lowest monthly average of daily lowest temperature) from “natural environment” of e-Stat.29)

According to the region categories in the NHNS, we stratified 47 prefectures into 12 regions: Hokkaido (Hokkaido), Tohoku (Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, Akita, Yamagata, and Fukushima), Kanto I (Saitama, Chiba, Tokyo, and Kanagawa), Kanto II (Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Yamanashi, and Nagano), Hokuriku (Niigata, Toyama, Ishikawa, and Fukui), Tokai (Gifu, Shizuoka, Aichi, and Mie), Kinki I (Kyoto, Osaka, and Hyogo), Kinki II (Nara, Wakayama, and Shiga), Chugoku (Tottori, Shimane, Okayama, Hiroshima, and Yamaguchi), Shikoku (Tokushima, Kagawa, Ehime, and Kochi), Kita-Kyushu (Fukuoka, Saga, Nagasaki, and Oita), and Minami-Kyushu (Kumamoto, Miyazaki, Kagoshima, and Okinawa).

Furthermore, we obtained population data for each prefecture stratified by age and sex from the VS in 2015.30) We calculated the SPR using the population of each prefecture.24) Age class was calculated every 5 years.

|

where, A is the number of prescriptions by age group and B = (population of age group) × (prescription incidence by age group in Japan). We used the therapeutic categories described by the Standard Commodity Classification Number of Japan.31) All generic names of drugs were verified and subsequently linked to the corresponding therapeutic category codes. According to the therapeutic category, all drugs were classified (S1 Table). The SPR of each prefecture was calculated. The SPR of 100 is equivalent to the national average. If the SPR is greater than 100, it indicates that, even when adjusted for sex and age in the prefecture, the prescribed amount of the drug is greater than the national average. Conversely, if the SPR is less than 100, it indicates that the prescribed amount of the drug is less than the national average.

A linear regression analysis was performed. The p-value was used to test the hypothesis that there is no relationship between the predictor and response, that is, to test the hypothesis that the true slope coefficient is zero.

To investigate the regional similarity in factors considered to be associated with hemorrhoidal disease, a hierarchical cluster analysis of the SPR of drugs of other therapeutic categories that did not include antihemorrhoidals (code: 255) and the associated factors with p values less than 0.05 in the above-mentioned linear regression analysis was performed. Clusters were formed using the Ward’s method with Euclidean distance. The number of clusters was determined based on the characteristics of each cluster.32) Due to the 2016 Kumamoto earthquake, there is no survey data of people who drank regularly, people who were smokers, and salt intake. Kumamoto prefecture is excluded from the cluster analysis.

The data were integrated in a relational database system using FileMaker Pro 13 software (FileMaker, Santa Clara, CA, U.S.A.). Data analyses were performed using JMP 13.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

A summary of regression coefficients between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals (code: 255) and those of other therapeutic categories is presented in S1 Table. One hundred and thirty-six therapeutic categories of drugs were reported in the 2nd NODJ (S1 Table). There were 54 therapeutic categories with p-values less than 0.05 in the linear regression analysis of the SPR of antihemorrhoidals (Table 1). The correlation coefficients between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and those of “antispasmodics (code: 124),” “antiarrhythmic agents (code: 212),” “antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators (code: 231),” “purgatives and clysters (code: 235),” “hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics (code: 112),” “psychotropic agents (code: 117),” and “opium alkaloids preparations (code: 811)” were 0.7474, 0.7366, 0.7184, 0.6501, 0.6320, 0.4571, and 0.4542, respectively (Table 1).

| Code | Therapeutic categories described by Standard Commodity Classification Number of Japan | Correlation coefficient | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 124 | Antispasmodics | 0.7474 | <0.0001 |

| 212 | Antiarrhythmic agents | 0.7366 | <0.0001 |

| 231 | Antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators | 0.7184 | <0.0001 |

| 223 | Expectorants | 0.7002 | <0.0001 |

| 259 | Other agents for uro-genital and anal organ | 0.6791 | <0.0001 |

| 214 | Antihypertensives | 0.6653 | <0.0001 |

| 235 | Purgatives and clysters | 0.6501 | <0.0001 |

| 332 | Hemostatics | 0.6484 | <0.0001 |

| 122 | Skeletal muscle relaxants | 0.6465 | <0.0001 |

| 391 | Agents for liver disease | 0.6428 | <0.0001 |

| 112 | Hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics | 0.6320 | <0.0001 |

| 225 | Bronchodilators | 0.6067 | <0.0001 |

| 319 | Other vitamin preparations | 0.6031 | <0.0001 |

| 114 | Antipyretics, analgesics and anti-inflammatory agents | 0.5916 | <0.0001 |

| 722 | Reagents for various function tests | 0.5603 | <0.0001 |

| 395 | Enzyme preparations | 0.5549 | <0.0001 |

| 213 | Diuretics | 0.5467 | <0.0001 |

| 133 | Antimotionsickness agents | 0.5370 | <0.0001 |

| 211 | Cardiotonics | 0.5325 | 0.0001 |

| 216 | Vasoconstrictors | 0.5315 | 0.0001 |

| 396 | Antidiabetic agents | 0.5222 | 0.0002 |

| 232 | Agent for peptic ulcer | 0.5176 | 0.0002 |

| 132 | Agents for otic and nasal use | 0.5158 | 0.0002 |

| 449 | Other antiallergic agents | 0.5066 | 0.0003 |

| 421 | Alkylating agents | 0.4939 | 0.0004 |

| 217 | Vasodilators | 0.4826 | 0.0006 |

| 719 | Other agents for dispensing use | 0.4818 | 0.0006 |

| 322 | Mineral preparations | 0.4803 | 0.0006 |

| 711 | Excipients | 0.4706 | 0.0008 |

| 249 | Other hormone preparations (including antihormone preparations) | 0.4698 | 0.0009 |

| 117 | Psychotropic agents | 0.4571 | 0.0012 |

| 811 | Opium alkaloids preparations | 0.4542 | 0.0013 |

| 264 | Analgesics, anti-itchings, astrigents and anti-inflammatory agents | 0.4416 | 0.0019 |

| 441 | Antihistamines | 0.4385 | 0.0021 |

| 613 | Antibiotic preparations acting mainly on Gram-positive, Gram-negative bacteria | −0.4245 | 0.0029 |

| 239 | Other agents affecting digestive organs | 0.4222 | 0.0031 |

| 229 | Other agents affecting respiratory organs | 0.4164 | 0.0036 |

| 224 | Antitussives and expectorants | 0.4036 | 0.0049 |

| 236 | Cholagogues | 0.4022 | 0.0051 |

| 313 | Vitamin B preparations (except Vitamin B1) | 0.3907 | 0.0066 |

| 218 | Agents for hyperlipidemias | 0.3885 | 0.0070 |

| 119 | Other agents affecting central nervous system | 0.3643 | 0.0118 |

| 323 | Saccharide preparations | −0.3554 | 0.0142 |

| 59 | Other crude drug and chinese medicine formulations | −0.3472 | 0.0168 |

| 325 | Proteins, amino acid and preparations | 0.3343 | 0.0216 |

| 339 | Other agents relating to blood and body fluides | 0.3317 | 0.0227 |

| 333 | Anticoagulants | 0.3298 | 0.0236 |

| 234 | Antacids | −0.3228 | 0.0269 |

| 123 | Autonomic agents | 0.3199 | 0.0284 |

| 131 | Agents for ophthalmic use | 0.3093 | 0.0344 |

| 263 | Dermatics for purulence | 0.3058 | 0.0366 |

| 399 | Agents affecting metabolism, n.e.c. | 0.3029 | 0.0385 |

| 616 | Antibiotic preparations acting mainly on acid-fast bacteria | −0.2961 | 0.0433 |

| 233 | Stomachics and digestives | 0.2929 | 0.0457 |

Regression coefficients between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and the results of specific medical checks from the 2nd NODJ and other factors from CSLC, NHNS, and natural environment are summarized in S2 Table. The number of applicable factors was 33 (S2 Table). There were 14 factors with p-values less than 0.05 in the linear regression analysis of the SPR of antihemorrhoidals shown in S2 Table (Table 2). The correlation coefficients between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and those of “average annual temperature,” “percentage of people who were smokers,” and “percentage of people who drank regularly” were −0.7204, 0.6002, and 0.3537, respectively (Table 2). The correlation coefficient between the SPR of antihemorrhoidals and average steps per day was −0.2504 (S2 Table). In the Hokkaido and Tohoku regions, the SPR of antihemorrhoidals was greater than 100, indicating that antihemorrhoidals were prescribed more in these regions than in the other prefectures. In addition, the SPR of purgatives and clysters was greater than 100 in the Hokkaido and Tohoku regions (data not shown). The lowest SPR of hemorrhoid preparations and the highest abdominal circumference and BMI were observed in Okinawa prefecture in the Minami-Kyushu region.

| Correlation coefficient | p-Value | Data set | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average annual temperature on 2016 (°C) | −0.7204 | <0.0001 | ES |

| Percentage of people who were smokers | 0.6002 | <0.0001 | ES |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in male (U/l) | 0.5869 | <0.0001 | NODJ |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in male (U/I) | 0.5472 | <0.0001 | NODJ |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) in female (U/I) | 0.5108 | 0.0002 | NODJ |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) in female (U/I) | 0.4369 | 0.0021 | NODJ |

| Salt intake (g/d) | 0.4198 | 0.0037 | ES |

| Triglyceride in male (mg/dL) | 0.3875 | 0.0071 | NODJ |

| γ-GTP in male (U/l) | 0.3798 | 0.0085 | NODJ |

| Percentage of people who drank regularly | 0.3537 | 0.0159 | ES |

| Diastolic blood pressure in female (mmHg) | 0.3478 | 0.0166 | NODJ |

| γ-GTP in female (U/l) | 0.3422 | 0.0186 | NODJ |

| Temperature difference on 2016 (°C) | 0.3014 | 0.0395 | ES |

| Diastolic blood pressure in male (mmHg) | 0.2970 | 0.0427 | NODJ |

NODJ: NDB Open Data Japan; ES: e-Stat.

A cluster analysis of the SPR of drugs of other therapeutic categories that did not include antihemorrhoidals (Table 1) and the associated factors (Table 2) was performed. The clustering analysis results were demonstrated as a dendrogram report (Fig. 2). The cluster means plots displayed the structure of observations in each cluster (Fig. 3). These plots connected line segments that represent each raw data in a data table and demonstrated how the clusters differ. Cluster 1 included Hokkaido and six prefectures in Tohoku and tended to have low average annual temperature values and high percentages of people who were smokers. The SPRs of “antispasmodics (code: 124),” “antiarrhythmic agents (code: 212),” “antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators (code: 231),” “purgatives and clysters (code: 235),” “hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics (code: 112),” “psychotropic agents (code: 117),” and “opium alkaloids preparations (code: 811)” in cluster 1 were comparatively high (Fig. 2). Clusters 2 and 3 included the Kanto I, Kanto II, Hokuriku, Kinki I, Kinki II, Chugoku, Shikoku, Kita-Kyushu, and Minami-Kyushu regions; the average annual temperature values, percentage of people who were smokers, and the SPRs of therapeutic categories were moderate. Cluster 4 included the Okinawa prefecture and tended to have high average annual temperature values and low percentage of people who were smokers. The SPRs of “antispasmodics (code: 124),” “antiarrhythmic agents (code: 212),” “antidiarrheals, intestinal regulators (code: 231),” “purgatives and clysters (code: 235),” “hypnotics and sedatives, antianxietics (code: 112),” “psychotropic agents (code: 117),” and “opium alkaloids preparations (code: 811)” were comparatively low in the Okinawa prefecture.

The axis ranges from two standard deviations above and below the mean. If a cluster mean falls beyond this range, the axis is extended to include it.

In this study, we aimed to determine the relationship between drug prescription trends based on SPR values using the population of each prefecture and several risk factors using the NODJ and related databases. In the present study, we demonstrated a relationship between the amounts of antihemorrhoidals (code: 255) and purgatives and clysters (code: 235) that might be used to treat constipation. Antispasmodics (cade: 124), such as scopolamine butylbromide, and antiarrhythmic agents (code: 212), such as cibenzoline and disopyramide, which are considered to have anticholinergic effects, frequently cause constipation as an adverse effect. Psychotropic agents (code: 117) were associated with the SPR of antihemorrhoidals. Benzodiazepines, which are anticholinergic drugs, were included in the “psychotropic agents (code: 117)” category. The correlation coefficient between the SPRs of psychotropic agents (code: 117) and purgatives and clysters (code: 235) was 0.5316 (data not shown). Opium alkaloids preparations (code: 811), which are known to cause constipation,12,13) were associated with the SPR of hemorrhoid preparations. Our results support the findings of previous studies5,7,11,33) reporting that constipation might be associated with an increased risk of hemorrhoids. We examined the effects of drugs based on the therapeutic categories according to the Standard Commodity Classification Number of Japan.31) As the symptoms of constipation are considered to differ with the type of drugs, future research should examine differences among drugs based on pharmacological action.

In this study, we interpreted the association between the incidence of hemorrhoids and regional characteristics in Japan using cluster analysis. Antihemorrhoidals are frequently used in the cold regions of Hokkaido and Tohoku in Japan. The lowest SPR of hemorrhoid preparations and the highest BMI and abdominal circumference were observed in the Okinawa Prefecture (data not shown). The treatments for hemorrhoids range from dietary and lifestyle modifications to radical surgery, depending on the degree and severity of symptoms.34–36) It is important for these prefectural governments to focus on the above factors when taking measures for health promotion. Lifestyle guidance on avoiding working in cold conditions may be particularly useful in Hokkaido and Tohoku.

Cluster analysis helps in grouping similar observations and classifying them into homogeneous clusters.32) As cluster analysis does not include objective variables, it is a method of data summarization, compared with other multivariate analysis methods, and an exploratory data analysis method. Therefore, data can be divided into any number of cluster formations, based on the subjectivity or viewpoint of a researcher, using cluster analysis. The validity of results can be judged only by external knowledge; if a researcher can interpret the results of data division, then it can be said that the number of clusters is “correct.”32) We finally set the number of cluster formations to 4. The determined characteristics for each cluster indicate the tendency of occurrence of factors common to the regions belonging to the cluster.

Several lifestyle modifications, such as exercising regularly, refraining from a sedentary lifestyle, refraining from straining on the toilet, improving anal hygiene, increasing the intake of dietary fiber and oral fluids, and avoiding drugs that cause constipation or diarrhea, might be useful to decrease the incidence of hemorrhoids; however, the evidence for these strategies is poor.34,35,37) As the SPR of antihemorrhoidals demonstrated a negative correlation with the average number of steps per day, regular exercise may slightly lower the risk of hemorrhoids.

Smoking causes both arterial and venous vascular injuries.9) An association between smoking and hemorrhoids has been reported, with the risk of developing hemorrhoidal vascular injuries among smokers being 2.4 times greater than that among nonsmokers.9) Our results also suggested an association between smoking and hemorrhoids. A previous study reported that alcohol consumption is not associated with the risk of developing hemorrhoids.38) Our results suggested a significant association between hemorrhoids and the percentage of people who drank regularly. Obesity has been reported to be related to hemorrhoids;8,38,39) however, our results did not show a clear association between hemorrhoids and abdominal circumference or BMI (S2 Table).

Although hemorrhoids are recognized as a common cause of rectal bleeding and anal discomfort, the true epidemiology of this disease is unknown because patients tend to self-medicate rather than seek proper medical attention.3) The biggest advantage of research using NODJ and e-Stat is that it is possible to clarify the current state of medical care in Japan. Although the NODJ does not contain data on individual patients and disease, the annually prescribed numbers of pharmaceutical products and specific medical examinations, such as BMI and laboratory data, are available.

There were some limitations to the present study using the NODJ. The receipt data, the source of the NDB data, are originally intended for billing medical fees. The percentage of specific health checkups that are covered in the NDB should be lower than the percentage of whole health insurance claims.40) NDB data are for specific health checkups only; therefore, we could not evaluate non-checkups.40,41) Therefore, it is necessary to pay attention to the possibility that the risk factor possession rate is underestimated in prefectures where the rate of specific health checkups is low. The limits of these NDB data also apply to NODJ. There is a possibility that the results will be misinterpreted during secondary use without an understanding about the system for requesting medical fee and billing requirements.22,40,41)

Furthermore, the medication usage records in the 2nd NODJ are restricted to the top 100 medication codes for each therapeutic category.22,25) Thus, not all medication codes in the NDB are included. Therefore, medications that we investigated are not representative of all medications for the respective therapeutic categories. The proportion of the investigated medications to all medications was assumed to have been different among the categories. These should be taken into account when interpreting the NODJ results.

OTC medications for hemorrhoids, purgatives and clysters, are available in Japan.42) However, it is difficult to know the exact amount of OTC drug used in each prefecture; therefore, we did not further investigate the influence of these OTC medications in the present study.

In this study, we investigated the correlation at the regional level. Regional correlation studies cannot show an association between individual-level exposure and outcome and cannot elucidate causal relationships and risk assessment of hemorrhoid at the individual level. Overall, it is important for prefectures to pay attention to these factors when formulating health promotion measures.

Several possible influencing factors were examined based on NODJ. Antihemorrhoidals are frequently used in Hokkaido and Tohoku in Japan; thus, it is important for these prefectural governments to focus on these factors when taking measures regarding health promotion. Our study will make a valuable contribution to information available for clinicians and will help improve the management of hemorrhoids.

This research was partially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI [Grant No. 17K08452].

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The online version of this article contains supplementary materials.