2014 年 79 巻 1 号 p. 185-192

2014 年 79 巻 1 号 p. 185-192

Background: Improvements in life expectancy among adults with congenital heart disease (ACHD) provide them with unique challenges throughout their lives and age-related psychosocial tasks in this group might differ from those of healthy counterparts. This study aimed to clarify age-related differences in psychosocial functioning in ACHD patients and determine the factors influencing anxiety and depression.

Methods and Results: A total of 133 ACHD patients (aged 20–46) and 117 reference participants (aged 20–43) were divided in 2 age groups (20 s and 30 s/40 s) and completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, Independent-Consciousness Scale, and Problem-Solving Inventory. Only ACHD patients completed an illness perception inventory. ACHD patients over 30 showed a significantly greater percentage of probable anxiety cases than those in their 20 s and the reference group. Moreover, ACHD patients over 30 who had lower dependence on parents and friends, registered higher independence and problem-solving ability than those in their 20 s, whereas this element did not vary with age in the reference participants. Furthermore, ACHD patients may develop an increasingly negative perception of their illness as they age. The factors influencing anxiety and depression in patients were aging, independence, problem-solving ability, and NYHA functional class.

Conclusions: Although healthy people are psychosocially stable after their 20 s, ACHD patients experience major differences and face unique challenges even after entering adulthood. (Circ J 2015; 79: 185–192)

Remarkable advances in medical and surgical management have enabled many infants with congenital heart diseases (CHD) to survive into adulthood. Thus, the number of adult CHD (ACHD) patients has increased during the past few decades, outnumbering pediatric patients.1,2 Most ACHD patients have a longer life span than was previously possible, but must deal with different challenges compared with those who do not have the disease. Consequently, some studies are now focusing not only on medical support throughout patients’ lives, but also patients’ psychosocial functioning and quality of life (QOL). It has been established that there is a significant comorbidity of mental disorders with various physical conditions,3–5 particularly for older age groups.6 Therefore, comprehensive studies are required in order to explore the mental disorders of patients with chronic physical conditions, including age-related changes in their psychological functioning.

Previous studies on the psychosocial features of ACHD patients were conducted by means of interview or questionnaire surveys,7–17 but results regarding the psychosocial state of patients have been inconsistent.18 According to some reports, psychiatric diagnostic interviews with ACHD patients indicate that between one- and two-thirds of patients exhibit psychiatric issues such as anxiety and mood disorders.7–9 Meanwhile, the results of questionnaire studies vary considerably: some have shown symptoms of anxiety/depression and low emotional functioning (ie, low independence, low self-esteem),10,11 whereas other studies have shown that emotional functioning does not differ from that of healthy individuals.12–15 Furthermore, adult patients with cyanosis or who have undergone the Fontan procedure have shown a higher ratio of depressive symptoms.16,17 The reasons for these inconsistent findings may include differences in sample size, recruiting sources, sociocultural background, etc. However, 2 other issues remain: many investigations did not have specified reference groups and some psychological differences in healthy participants have not yet been ascertained.18 Moreover, clear-cut results have not been obtained because the effects of age were not taken into account, as the targeted age range of ACHD patients in previous studies has been very broad.

A patient’s age may affect psychosocial health and QOL,6,19–21 but comprehensive analyses of differences across age groups in ACHD patients have not been properly implemented. Because the tasks that patients must perform generally change with their developmental stage, the issues they must face will also change accordingly. Thus far, only minimal research has been conducted into the relationship between ACHD patients’ psychosocial functioning and age.19–21 In order to provide appropriate and effective support to patients, it is essential that we consider their developmental stage.

Therefore, the present study used a reference group and aimed to (1) clarify how psychosocial functioning, such as the presence and severity of anxiety and depression, differ according to the age of ACHD patients’ and (2) determine the factors that influence ACHD patients’ anxiety and depression with age.

ACHD patients, all monitored by the same physician (M.N.), were recruited from the databases of 2 institutions: the Tokyo Clinic and the Southern Tohoku General Hospital in Japan. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosed with CHD and had medical records that could be reviewed; (2) able to read and complete the consent form and questionnaires, which were written in Japanese; and (3) between the ages of 20 and 49. The exclusion criteria were having any cognitive and/or physical limitations that would prevent the potential participant from filling out the questionnaires.

The reference group consisted of 117 participants (65 women; age range 20–43 years) recruited from a local seminar, local universities, or who were parents of students at local schools.

ProcedureThe 258 eligible patients received by mail an information letter, a set of questionnaires, and a stamped and addressed return envelope. An informed consent form was included and had to be personally signed by the patient. They were asked to complete the set of questionnaires themselves and to return them within 3 weeks. Informed consent was given by each patient and the study protocol was approved by the medical ethics committee of the Southern Tohoku General Hospital, Japan.

Variables and MeasuresDemographic Variables and Disease Severity Demographic questions were included to obtain each participant’s age, sex, education level, condition of employment, marital status, and presence/absence of children.

Based on the initial diagnosis or the specific type of operation, the cardiac defects were classified as being of “simple”, “moderate”, or “great” complexity in accordance with the definitions used in the 2008 ACC/AHA ACHD Guidelines.22 To assess current functional status, the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classes were used. They were grouped as NYHA I vs. NYHA II and III, because the numbers of patients classified as NYHA II and III were small.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale23 This scale measures the presence and degree of anxiety and depression symptoms. We used the Japanese version of this scale,24 which consists of 7 items (each rated on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3) for each of 2 subscales (anxiety and depression). Scores on each subscale range between 0 and 21. Scores of 0–7 correspond to not having anxiety or depression symptoms (hereafter, “no” case), 8–10 to “possible” anxiety or depression, and 11–21 to “probable” anxiety or depression. A higher score indicates a greater likelihood and severity of anxiety or depression symptoms. Reliability scores (Cronbach’s alpha) were 0.83 for anxiety and 0.63 for depression.

Independent-Consciousness Scale25 This scale was originally created in Japanese and measures the transition from dependence to independence in adolescents. For this study, 5 items were selected from 2 subscales: “Independence” (the ability to make decisions regarding one’s future and any difficulties encountered) and “Dependence on parents” (dependence on parents resulting from an inability to make one’s own decisions and the sense of security obtained from being with parents). Additionally, in order to measure their relationships with friends, a new subscale was created, called “Dependence on friends”, which we designed by replacing the word “parents” in all items on the “Dependence on parents” subscale with the word “friends”. The Independent-Consciousness scale, with the inclusion of the newly created subscale, included 15 items in total, each rated on a 5-point scale, as per the original version (and for all subsequent rating procedures). The average for each subscale was calculated and used in our analyses. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.72 for “Independence”, 0.86 for “Dependence on parents”, and 0.82 for “Dependence on friends”.

Problem-Solving Inventory (PSI)26 The PSI measures the social skills used for effectively solving problems encountered in daily life. We used a Japanese translation,27 which comprises 32 items in the original version; however, we used a short version (14 items)11 of the scale, created by Heppner and Petersen. Items were rated on a six-point scale; the PSI score was calculated by averaging the 14 items. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.83.

Illness Perception We assessed illness perception using a set of 12 items developed for this study, which were derived from previous research28 and qualitative interviews with ACHD patients in a pilot study. Items were rated on a 5-point scale. Through repeated factor analyses (using the maximum likelihood method with a promax rotation), 2 factors were extracted, each with 4 items. We eliminated 4 items because they either had small factor loadings in the post-rotation factor matrix or had high loadings with other factors. Cumulative contribution was 54.5% and the factor loading range of items was from 0.613 to 0.936 for the first factor and from 0.412 to 0.760 for the second factor. Cronbach’s alphas were 0.84 and 0.76, respectively. The first factor included items that assessed individuals’ negative perceptions of their illness (eg, “I cannot do what I want because of my illness.”), and thus was labeled “Negative perception”. The second factor included items that assessed individuals’ desires for their illness to be understood by friends and acquaintances (eg, “I want people around me to understand the seriousness of my illness.”), and thus was labeled “Desire to be understood”. This score was calculated by averaging each of the subscale items.

Statistical AnalysisData analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Japan Inc, Tokyo, Japan). To examine group differences, Fisher’s exact tests for categorical data were performed, together with t-tests and ANOVAs for continuous variables. To identify the associations between depression/anxiety and other variables, Spearman’s correlation and hierarchical regression analysis were calculated. We performed hierarchical regression analysis for ACHD patients, with the dependent variables related to anxiety and depression and the explanatory variables organized in 4 blocks: demographics, illness perception, independent consciousness, and social problem solving. These 4 blocks were determined by reference to a previous study.11 The significance level was set at P<0.05 for all analyses.

A total of 258 ACHD patients were contacted by mail and of them, 133 (51.6% response rate) returned completed questionnaires with consent forms. Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics, as well as the distribution of the cardiac defects and the NYHA functional class of the ACHD patients. Table 2 presents the most common cardiac defects classified by complexity. As shown in Table 1, compared with the reference group, there were fewer graduates of higher education, fewer full-time workers, more part-time workers, and more homemakers among ACHD patients (residual analysis: P<0.05, respectively).

| Variable | ACHD patients, n (%) |

Reference group, n (%) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years, mean±SD (range)) | 28.77±6.83 | 29.39±5.07 | NS |

| 20–29 | 88 (66.2) | 56 (47.9) | |

| 30–46 | 45 (33.8) | 61 (52.1) | |

| Female | 89 (66.9) | 65 (55.6) | NS |

| Ethnicity | Japanese | Japanese | |

| Education level | 0.002 | ||

| >High school education | 106 (80.9) | 110 (94.0) | |

| Employment | 0.004 | ||

| Full-time worker | 74 (55.6) | 82 (70.1) | |

| Part-time worker | 18 (13.5) | 6 (5.1) | |

| Unemployed | 4 (3.0) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Homemaker | 20 (15.0) | 6 (5.1) | |

| Student | 15 (11.3) | 21 (17.9) | |

| Other | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.9) | |

| Marital status | NS | ||

| Married | 43 (32.3) | 47 (40.2) | |

| Have child/children | 33 (25.0) | 34 (29.1) | NS |

| NYHA: total/20–29 years, 30–46 years* | 0.00 | ||

| I | 119 (89.5)/80 (90.9), 39 (86.7) | ||

| II, III | 14 (10.5)/8 (9.1), 6 (13.3) | ||

| Defect complexity: total/20–29 years, 30–46 years** |

NS | ||

| Simple | 35 (26.3)/22 (25.0), 13 (28.9) | ||

| Moderate | 41 (30.8)/24 (27.3), 17 (37.8) | ||

| Great | 57 (42.9)/42 (47.7), 15 (33.3) |

*Fisher’s exact test for 2 age groups×NYHA was not significant. **Fisher’s exact test for 2 age groups×defect complexity was not significant. ACHD, adult congenital heart disease; NS, not significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class.

| Simple CHD (n=35) | |

| Repaired ASD/VSD | 15 |

| Isolated small ASD/VSD | 14 |

| Isolated aortic valve disease | 3 |

| Other simple defects | 3 |

| Moderate complexity CHD (n=41) | |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 13 |

| VSD with any valve problems and/or obstruction | 9 |

| Atrioventricular canal/septal defects | 4 |

| Anomalous pulmonary venous drainage (partial or total) | 4 |

| Coarctation of the aorta | 3 |

| Pulmonary valve stenosis | 2 |

| Other defects of moderate complexity | 6 |

| Great complexity CHD (n=57) | |

| Univentricular anatomy (Fontan procedure) | 14 |

| Repaired transposition of the great arteries (atrial or arterial procedure) | 12 |

| Conduits (valved or non-valved) | 12 |

| Cyanotic heart disease or Eisenmenger syndrome | 5 |

| Congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries | 4 |

| Double outlet ventricle | 5 |

| Single ventricle | 2 |

| Other defects of great complexity | 3 |

ASD, atrial septal defect; CHD, congenital heart disease; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

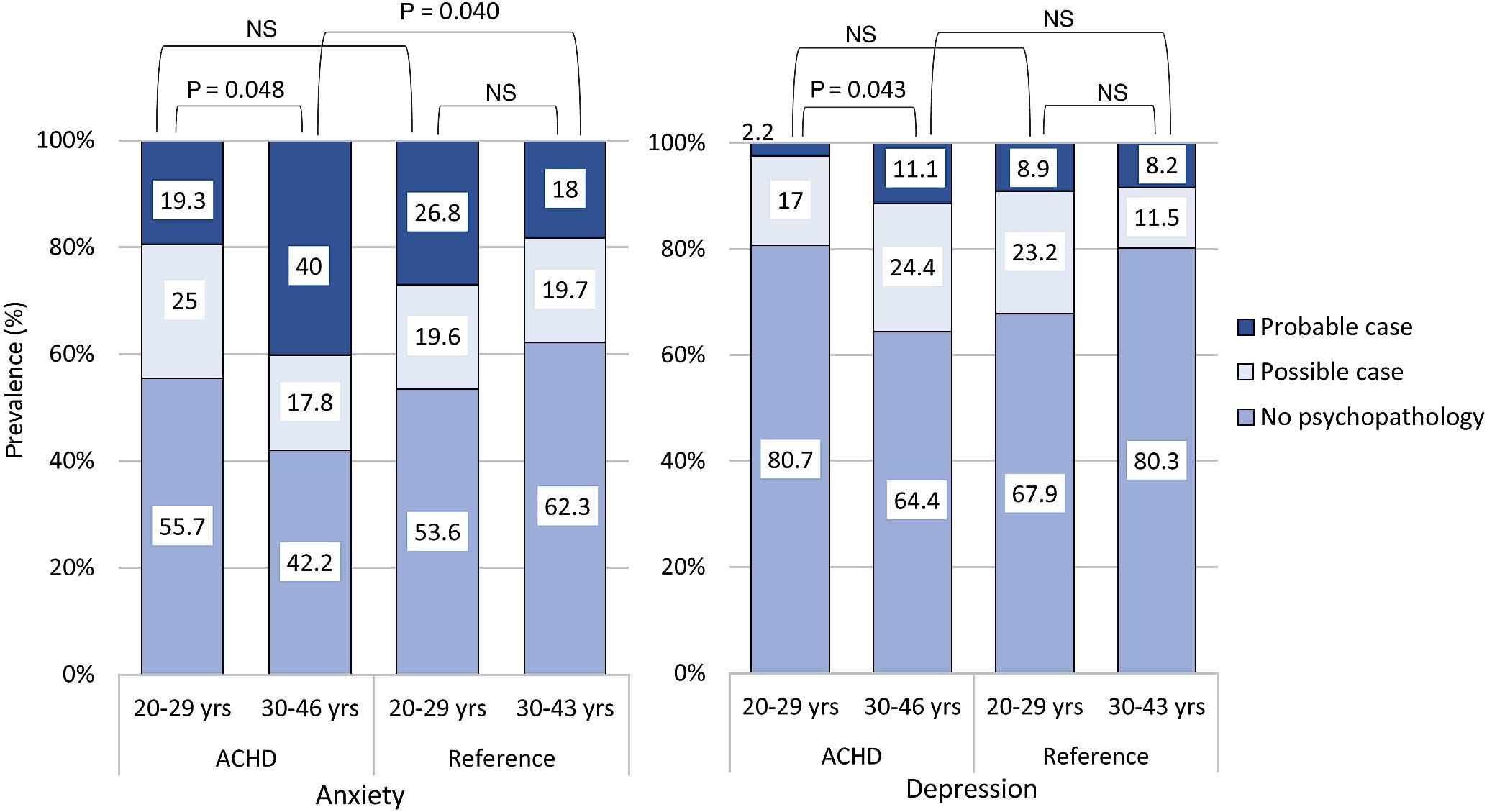

As shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences in the total scores for anxiety and depression between the ACHD and reference groups. According to symptom level analyses (Figure), ACHD patients over 30 years of age (hereafter, “patients over 30”) presented a significantly higher number of “probable” clinical anxiety cases (scores 11–21) and fewer “no” cases (scores 0–7) than did matched reference group participants (residual analysis: P<0.05, respectively). Furthermore, there were significant age differences in the ratios of the 3 symptom levels of anxiety and depression only in the ACHD group. As the results of the residual analysis showed, ACHD patients over 30, compared with those in their 20 s, had significantly more “probable” cases of anxiety and depression and fewer “no” cases of depression (residual analysis: P<0.01, respectively).

| ACHD patients | Reference group | t-test | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | t-test (2 vs. 3) | Age | t-test (5 vs. 6) | 1 vs. 4 | 2 vs. 5 | 3 vs. 6 | ||||||||||

| 1. Total |

2. 20–29 years |

3. 30–46 years |

95% CI | P value | 4. Total |

5. 20–29 years |

6. 30–43 years |

95% CI | P value | 95% CI | P value | 95% CI | P value | 95% CI | P value | |

| HADS† mean | ||||||||||||||||

| Anxiety (SD) |

7.90 (4.03) |

7.56 (3.67) |

8.58 (4.65) |

−2.61, 0.57 |

NS | 7.45 (4.21) |

7.76 (4.63) |

7.15 (3.79) |

−0.95, 2.18 |

NS | −1.48, 0.58 |

NS | −1.24, 1.66 |

NS | −3.12, 0.27 |

NS |

| Depression (SD) |

5.53 (3.07) |

5.17 (2.61) |

6.22 (3.67) |

−2.28, 0.17 |

NS | 5.97 (2.95) |

6.00 (3.08) |

5.93 (2.84) |

−1.03, 1.16 |

NS | −0.31, 1.19 |

NS | −0.12, 1.77 |

NS | −1.60, 1.02 |

NS |

| Independent-Consciousness†† mean | ||||||||||||||||

| Independence (SD) |

3.74 (0.66) |

3.66 (0.64) |

3.92 (0.69) |

−0.51, −0.02 |

0.037 | 3.67 (0.69) |

3.70 (0.72) |

3.64 (0.66) |

−0.20, 0.31 |

NS | −0.25, 0.09 |

NS | −0.19, 0.27 |

NS | −0.55, −0.02 |

0.034 |

| Dependence on parents (SD) |

3.35 (0.92) |

3.49 (0.86) |

3.06 (0.98) |

0.09, 0.78 |

0.008 | 3.25 (0.84) |

3.19 (0.83) |

3.31 (0.84) |

−0.43, 0.19 |

NS | −0.32, 0.12 |

NS | −0.60, −0.02 |

0.014 | −0.10, 0.60 |

NS |

| Dependence on friends (SD) |

3.23 (0.84) |

3.37 (0.77) |

2.96 (0.91) |

0.84, 0.72 |

0.008 | 3.36 (0.71) |

3.32 (0.80) |

3.38 (0.62) |

−0.31, 0.21 |

NS | −0.70, 0.32 |

NS | −0.30, 0.23 |

NS | 0.10, 0.73 |

0.025 |

| PSI# mean (SD) |

3.79 (0.61) |

3.70 (0.63) |

3.96 (0.54) |

−0.47, −0.05 |

0.039 | 3.86 (0.67) |

3.82 (0.71) |

3.89 (0.63) |

−0.32, 0.18 |

NS | −0.95, 0.22 |

NS | −0.11, 0.34 |

NS | −0.30, 0.16 |

NS |

| Illness Perception## mean | ||||||||||||||||

| Negative perception (SD) |

2.40 (1.11) |

2.19 (1.00) |

2.81 (1.22) |

−1.04, −0.20 |

0.005 | |||||||||||

| Desire to be understood (SD) |

2.74 (0.87) |

2.59 (0.82) |

3.04 (0.89) |

−0.77, −0.14 |

0.004 | |||||||||||

*Total=133; 20–29 years=88, 30–46 years=45. **Total=117; 20–29 years=56, 30–43 years=61. †HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, total score range 0–21; ††Independent-Consciousness, score range 1–5; #PSI, Problem Solving Inventory, score range 1–6; ##Illness Perception, score range 1–5. CI, confidence interval. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Prevalence of symptom levels of anxiety and depression in adult congenital heart disease patients (total=133; 20–29 years=88, 30–46 years=45) and a reference group (total=117; 20–29 years=56, 30–43 years=61).

Comparisons among the cardiac defect subgroups of the ACHD group showed there were no significant differences in either the total scores or the 3 symptom levels of anxiety and depression. However, there were significant differences by NYHA class, both according to the total mean scores for anxiety (P=0.008) and across the 3 symptom levels of anxiety (Fisher’s exact tests: P=0.015). NYHA II and III patients presented significantly higher anxiety scores and more “probable” cases (residual analysis: P<0.01) and fewer “no” cases (residual analysis: P<0.05) of anxiety than did NYHA I patients.

Other Aspects of Psychosocial FunctioningAs shown in Table 3, there were no significant differences in the total scores of the other psychosocial functioning measures between the ACHD and reference groups. Age-specific scores in psychosocial functioning showed that the ACHD patients in their 20 s had significantly higher dependence on parents, while patients over 30 had higher independence and lower dependence on friends than did the age-matched references. Only in the ACHD group did we find age differences, with patients over 30 having significantly higher scores on the “Independence” subscale and “PSI”, and significantly lower scores on “Dependence on parents” and “Dependence on friends” than did those in their 20 s. There were no significant differences among the cardiac defect subgroups or NYHA class on any scales.

Illness Perception Illness perception was evaluated in the ACHD patients only. As shown in Table 3, there were significant differences between the 2 age groups, with patients over 30 having significantly higher scores on “Negative perception” and “Desire to be understood” than did those in their 20 s.

The cardiac defect and NYHA class subgroups showed that patients with defects of “moderate” or “great” complexity had significantly higher scores on “Negative perception” (P<0.001) and “Desire to be understood” (P=0.033) and patients with NYHA II and III class had significantly higher scores on both illness perception subscales (P<0.001 for “Negative perception”, P=0.003 for “Desire to be understood”).

Psychosocial Factors Associated With Anxiety and DepressionAs shown in Table 4, symptoms of anxiety and depression exhibited a significant negative correlation with “Independence” and “PSI” for almost all participants. Furthermore, anxiety in patients over 30 was significantly and positively correlated with “Desire to be understood” and NYHA class.

| ACHD group | Total (n=133) | 20–29 years (n=88) | 30–46 years (n=45) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | Depression | |

| Independence | −0.31** | −0.38** | −0.32** | −0.36** | −0.33* | −0.48** |

| Dependence on parents | −0.10 | −0.19* | −0.13 | −0.14 | −0.07 | −0.24 |

| Dependence on friends | −0.04 | −0.19* | −0.10 | −0.17 | 0.14 | −0.14 |

| Problem-Solving Inventory | −0.33** | −0.27** | −0.28** | −0.26* | −0.46** | −0.35* |

| Negative perception | 0.21* | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| Desire to be understood | 0.28** | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.35* | 0.24 |

| NYHA | 0.24** | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.34* | 0.16 |

| Defect complexity | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.00 | −0.10 | 0.15 | −0.03 |

| Anxiety | 0.53** | 0.50** | 0.58** | |||

| Reference group | Total (n=117) | 20–29 years (n=56) | 30–43 years (n=61) | |||

| Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | Depression | Anxiety | Depression | |

| Independence | −0.36** | −0.38** | −0.38** | −0.20 | −0.30* | −0.57** |

| Dependence on parents | 0.10 | −0.18 | 0.06 | −0.31* | 0.16 | 0.00 |

| Dependence on friends | 0.22* | −0.07 | 0.25 | −0.10 | 0.15 | −0.05 |

| Problem-Solving Inventory | −0.39** | −0.45** | −0.41** | −0.33* | −0.32* | −0.56** |

| Anxiety | 0.40** | 0.36** | 0.41** | |||

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. Abbreviations as in Table 1.

As shown in Table 5, in the hierarchical regression analysis for the ACHD group, anxiety and depression symptoms were positively associated with age and NYHA class, and negatively associated with “Independence”. Additionally, anxiety was negatively associated with “PSI” scores, and depression was negatively associated with graduates of higher school education and “Dependence on parents”. The model explained 32.5% and 33.3% of the variance in anxiety and depression symptoms, respectively.

| Independent variable | Anxiety | Depression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | P value | β | 95% CI | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age (30–46) | 0.21 | 0.15, 3.45 | 0.033 | 0.25 | 0.35, −2.83 | <0.001 |

| Sex (female) | 0.05 | −1.13, 1.99 | NS | −0.00 | −1.18, −1.15 | NS |

| Education | ||||||

| >High school education | −0.13 | −3.10, 0.48 | NS | −0.18 | −2.70, −0.02 | 0.047 |

| Employment | ||||||

| Full-time worker/homemaker | −0.08 | −2.47, 1.06 | NS | −0.26 | −2.40, −0.24 | NS |

| Married (yes) | −0.22 | −4.42, 0.62 | NS | −0.13 | −2.75, −1.11 | NS |

| Have a child (yes) | 0.03 | −2.39, 3.00 | NS | 0.05 | −1.68, −2.36 | NS |

| NYHA (II, III) | 0.21 | 0.38, 5.41 | 0.024 | 0.22 | 0.38, −4.15 | 0.019 |

| Defect complexity | ||||||

| Moderate | −0.16 | −3.22, −0.46 | NS | –0.22 | −1.61, −1.15 | NS |

| Great | −0.06 | −2.31, −1.35 | NS | –0.04 | −2.71, −0.04 | NS |

| ΔR2 | 0.15 | ΔF=2.25 | 0.023 | 0.15 | ΔF=2.27 | 0.022 |

| Illness perception | ||||||

| Negative perception | 0.12 | −0.35, −1.24 | NS | 0.03 | −0.54, −0.68 | NS |

| Desire to be understood | 0.16 | −0.20, 1.70 | NS | 0.02 | −0.65, −0.81 | NS |

| ΔR2 | 0.05 | ΔF=3.27 | 0.041 | 0.00 | ΔF=0.09 | NS |

| Independent-Consciousness | ||||||

| Independence | −0.29 | −2.78, −0.73 | 0.001 | −0.34 | −2.33, −0.84 | <0.001 |

| Dependence on parents | −0.11 | −1.28, −0.36 | NS | −0.24 | −238, −0.20 | 0.010 |

| Dependence on friends | −0.04 | −1.07, −0.71 | NS | −0.11 | −1.05, −0.25 | NS |

| ΔR2 | 0.09 | ΔF=4.61 | 0.004 | 0.18 | ΔF=9.99 | <0.001 |

| Problem-Solving Inventory | −0.29 | −3.32, −0.56 | 0.006 | −0.12 | −1.63, −0.42 | NS |

| ΔR2 | 0.05 | ΔF=7.78 | 0.006 | 0.01 | ΔF=1.37 | NS |

| Total R2 | 0.33 | F=3.62 | <0.001 | 0.33 | F=3.76 | <0.001 |

R2, coefficient of determination; ΔR2, R2 change. Other abbreviations as in Tables 1,3.

This study highlighted the influence of age on the psychosocial features of ACHD patients and revealed the factors associated with anxiety and depression. Our results indicated that ACHD patients show more conspicuous attitudinal differences with age.

Anxiety and DepressionOur results showed a notable increase in psychopathological symptoms among patients over 30 compared with patients in their 20 s and the matched referents. Although no differences were recorded between the age groups in the reference group, there was a 2-fold increase in probable clinical anxiety cases and a 5-fold increase in probable clinical depression cases for ACHD patients aged over 30. Previous studies that used the same measure of psychopathology as the present study (ie, HADS) noted the following results: in both a British study29 (patients’ mean age was 37.2) and an Iranian study10 (mean age was 33.2), 13% and 38.3% (26.3% in our study) of ACHD patients, respectively, were probable anxiety cases, and 5% and 17.9% (5.3% in our study), respectively, were probable cases of depression. An Australian study30 focusing on adolescent patients with heart disease (mean age was 16; 90% diagnosed with CHD) showed that 10% were probable anxiety cases and 3% were probable cases of depression. The results differed among countries, but, overall, the number of patients with anxiety and depression increased with age.

So, what factors lead to the increased anxiety and depression with age? Moons et al21 showed that a patient group, 18–66 years old, presented significantly lower values compared with a reference group with regards to “future” or “financial means and/or marital well-being” as important aspects of QOL. This shows that a larger proportion of ACHD patients have an ambiguous view of their future, rather than a positive view. This ambiguity may lead to a higher level of anxiety and depression in these patients with age.

Other Aspects of Psychosocial Functioning and Illness PerceptionThe reference group generally maintained a stable psychological course throughout their lives, without any noticeable differences after their 20 s; in contrast, the ACHD patients attempted to become much more independent after 30 years of age. Specifically, ACHD patients in their 20 s had a higher dependence on parents while those over 30 had a higher independence than did the age-matched reference group. It seems that patients commence asserting their independence in their adulthood instead of in their adolescence. It is important to offer patients appropriate support to help smooth their transition from adolescence to adulthood.

Our research also shows that ACHD patients develop an increasingly negative perception of their illness as they age, as well as a stronger desire to be understood by others. Previous study indicated that most ACHD patients regard their health condition as the main factor contributing to their QOL with age,21 which explains why they pay so much attention to their disease. This attention may cause them to develop an increasingly negative perception of it, which in turn, perhaps enhances their desire to have their condition understood by others.

Association of Psychosocial Factors With Anxiety and DepressionAnxiety and depression were found to be closely related to patients’ aging, so healthcare personnel must pay close attention to the issues that develop with age in ACHD patients. In addition, independence and problem-solving ability were strongly and negatively associated with anxiety and depression. In other words, symptoms of anxiety and depression increase when such psychosocial factors are low. A previous study also showed that problem-solving ability and independence are related to mental health;11 thus, encouraging the development of these aspects in patients (ie, patients having adequate relationships with their parents and friends in accordance with their age and making decisions about their future based on knowledge of their physical condition) will help prevent psychopathological symptoms from developing. In addition, it is considered that these approaches help patients transition smoothly from adolescence to adulthood.

Moreover, anxiety and depression, especially anxiety in ACHD patients aged over 30, were found to be related to NYHA class. A previous study showed that patients’ QOL and psychological functioning were much more influenced by their current physical functional status, such as NYHA class, than by their initial diagnosis,31 and this finding was supported by our study. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, most ACHD patients regard their health condition as the main factor contributing to their QOL with age.21 Thus, mainly the patients aged over 30 with higher NYHA class worry about their health condition and their future, which might make them anxious. Healthcare personnel should pay attention to patients’ physical status, because it will play a major role in preventing escalation of their psychological issues.

Additionally, feelings of anxiety, especially in ACHD patients aged over 30, were significantly related to illness perception. Therefore, trying to understand patients’ subjective perceptions of their condition would be helpful in preventing exacerbation of anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, symptoms of depression in patients were negatively associated with dependence on parents. This suggests that a certain degree of dependence on parents was necessary for ACHD patients’ mental well-being, because it was important for them to join adult society while being supported in their independence by those closest to them.

Study LimitationsThe main limitation is generalizability: this study was conducted at 2 ACHD centers with patients under the regular care of 1 doctor; therefore, these results may not be generalized to patients who are not under constant medical supervision or who are not currently engaged in regular CHD follow-up at a specialized center. The present study also used a cross-sectional design, rather than a longitudinal one. If the longitudinal design had been used, it would have been possible to present a more definite picture of the age-related differences in psychopathological symptoms and psychosocial functioning in ACHD patients.

This comparative study found that while the reference group was psychosocially stable in their 20 s, 30 s, and 40 s, ACHD patients can experience drastic changes in psychosocial functioning and face unique challenges, even after entering adulthood. Therefore, it is important to identify the issues they will face in subsequent developmental stages, and to create a management strategy that will enable them to lead more stable lives even in later years. To that end, healthcare personnel should provide patients with suitable information and they should periodically address their complaints and worries. It is also important to help patients become increasingly independent and develop better social skills starting from childhood. In summary, healthcare personnel should try to understand CHD patients’ developmental process throughout their increasingly long lives, and provide them with the appropriate support at each stage.

The authors thank all the patients who participated in this study for their cooperation, because this research would not have been possible otherwise.

This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant Number 22730556 offered to JE. However, this body was not involved in the design or conduct of the study nor in the decision to submit it for publication.