2016 年 80 巻 8 号 p. 1750-1755

2016 年 80 巻 8 号 p. 1750-1755

Background: The regional clinical alliance path (RCAP) after discharge from an acute-phase hospital is emerging as a tool for bridging acute-phase treatment and chronic-phase disease management. However, the optimal application of RCAP for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains unknown in Japan, and therefore a nationwide survey of hospitals was conducted.

Methods and Results: In 2009, questionnaires were sent to 1,240 cardiology training hospitals authorized by the Japanese Circulation Society. The response rate was 62.9% (780/1,240). Of the 780 responding hospitals, 708 treated AMI, and in these hospitals the number of AMI patients and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures performed were, respectively, 59±52 and 200±206 per year. The implementation rate of emergency PCI was high (91%), but that of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation (OPCR) was very low (18%). The implementation rate of RCAP after AMI was significantly lower (10%) than after stroke (57%). Cardiac rehabilitation (CR) was adopted as part of RCAP in only 19% (13/70) of currently operating RCAP programs.

Conclusions: This first Japanese nationwide survey of RCAP after AMI showed that in contrast to the broad dissemination of acute-phase invasive treatment for AMI, there was infrequent implementation of OPCR, RCAP after AMI, and RCAP including CR. It will be necessary to broaden the use of RCAP after AMI, including OPCR. (Circ J 2016; 80: 1750–1755)

The “regional clinical alliance path” (RCAP), also called “regional liaison critical pathway” or “community cooperation critical pathway”, is a patient care program in which acute-phase specialized hospitals and chronic-phase medical institutions (family physicians and/or rehabilitation facilities) work cooperatively to manage post-acute phase patients in the community. In Japan, the Medical Service Law was revised in 2007 to promote RCAP, aimed at division of roles between acute- and chronic-phase medical institutions and a seamless transition of medical care from the acute to the chronic phase. Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) was listed as a target disease of RCAP.1,2 In response to this government health policy, efforts to promote RCAP for AMI have been started in many regions in Japan.3–6 However, neither the current implementation status nor the details of RCAP programs have been investigated.

Editorial p 1697

Although the acute-phase mortality rate for AMI has been strikingly reduced in recent years,7 the long-term cardiovascular event rate remains high.8–10 Therefore, disease management after hospital discharge has become more important in order to improve long-term prognosis. In addition, because the length of hospital stay has been substantially shortened by the widespread use of primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)/reperfusion therapy, the importance of cooperation between cardiologists in acute-phase hospitals and family physicians in the community has increased.

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR), a post-discharge patient care system consisting of exercise therapy and patient education, has been shown to improve long-term prognoses in patients with AMI, and is therefore strongly recommended by clinical practice guidelines.11–16 However, the implementation of post-discharge outpatient CR (OPCR) has been reported to be remarkably poor in Japan.17–20 In addition, the extent to which OPCR is adopted in RCAP is unknown.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to clarify the current status of both the implementation of RCAP for AMI and the incorporation of OPCR in RCAP in Japan. To this end, we conducted a nationwide survey of all cardiology training hospitals (THs) in Japan authorized by the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS).

This study was conducted as a nationwide survey by “The Research Group of Cardiovascular Disease (20C-7) Granted from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.” At the time of this study in 2009, 934 hospitals were authorized by the JCS as “THs” for Board-Certified Members of the JCS, and 306 were designated as “associated hospitals” (AHs). Questionnaires were sent to these 1,240 cardiology THs and AHs. The response rates were 63% (780/1,240) overall, 64% (597/934) for THs, and 60% (183/306) for AHs. We also analyzed data for RCAP in 961 hospitals treating stroke.

The questionnaire surveyed (1) hospital data: number of beds, number of cardiology beds, number of cardiologists, number of coronary care unit beds, presence of a CR facility; (2) cardiology practice data in 2009: number of hospitalized patients with AMI, implementation of coronary angiography, implementation of PCI, implementation of emergency PCI, number of cardiac surgeries and coronary artery bypass graft surgeries (CABGs); (3) implementation of CR: acute-phase CR for patients with AMI, recovery-phase CR, patient education program-formulated exercise prescriptions based on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPX) with respiratory gas analysis, and presence of OPCR programs after hospital discharge; and (4) implementation of path: intra-hospital clinical path and RCAP. The data sheets were collected and analyzed at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and Rehabilitation, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Center.

We evaluated (1) the status of both cardiology care for AMI and the implementation of CR and RCAP after AMI, (2) the implementation rates of RCAP in AMI and stroke hospitals, (3) characteristics of hospitals implementing and not implementing RCAP, (4) reasons for not implementing RCAP after AMI, and (5) content of RCAP after AMI.

Statistical AnalysisNumerical data are presented as average±standard deviation. Data were compared between the RCAP and non-RCAP hospital groups by the unpaired t-test for numerical data and by the chi-square test for categorical data. P<0.05 was considered to be statically significant.

Of the 780 hospitals surveyed, we analyzed 708 that were treating AMI patients.

Hospital Data for Care of AMIThe hospital data are shown in Table 1. The data for total number of beds, annual numbers of AMI patients, annual PCI volume, and the number of cardiologists indicated that the hospitals surveyed were, on average, middle to large sized. Approximately half of them had a cardiac surgery department.

| Hospital data | (n=780) |

|---|---|

| No. of hospital beds | 415±240 |

| No. of cardiology beds | 39±25 |

| No. of cardiologists | 6.5±7.1 |

| Presence of CCU | 69% (490/708) |

| No. of CCU beds | 3.7±3.8 |

| Presence of cardiac surgery department | 54.2% (384/708) |

| Annual no. of patients with AMI | 59±52 |

| Annual no. of coronary angiography | 560±583 |

| Annual no. of PCI | 200±206 |

| Annual no. of cardiac surgery | 53±88 |

| Annual no. of CABG | 23±37 |

| Average length of stay for AMI (days) | 15.5±6.5 |

| Approved facility for CR | 27.8% (197/708) |

| Facility category I | 21.8% (154/708) |

| Facility category II | 6.1% (43/708) |

| Presence of specialized CR room | 28.2% (200/708) |

| Implementing acute-phase CR for AMI | 57.5% (407/708) |

| Implementing outpatient CR program | 17.7% (125/708) |

| Implementing patient education program | 24.2% (171/708) |

| Implementing cardiopulmonary exercise testing | 20.5% (145/708) |

| Implementing exercise prescription | 23.4% (166/708) |

| RCAP after AMI | 10.0% (70/708) |

Values are mean±standard deviation. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCU, coronary care unit; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCAP, regional clinical alliance path.

With regards to implementation of CR for AMI, only 58% of the hospitals had acute-phase CR programs, and only 28% and 24% had their own CR room and patient education program on CR, respectively. In addition, only 20.5% were implementing CPX with expired gas analysis, and 23.4% prescribed exercises based on the results of CPX.

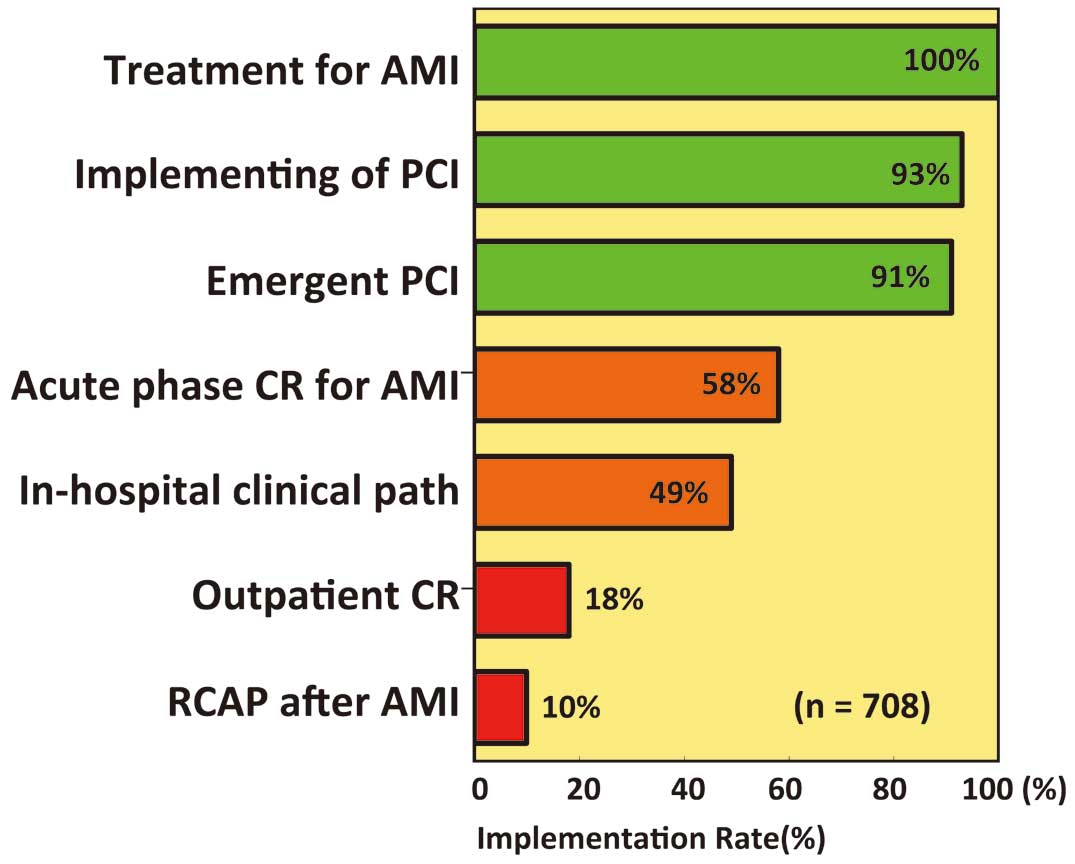

Figure 1 depicts the implementation rates of medical care for AMI patients among the 708 treating hospitals. Although the rates of implementation of PCI and emergency PCI were very high, the rates of implementation of outpatient CR or RCAP were very low. Only 18% (125/708) of the hospitals were implementing OPCR programs after discharge, and 10% (70/708) were implementing RCAP after AMI.

Details of treatment in 708 hospitals treating AMI patients. In contrast to the higher rate of implementation of PCI, the implementation rates for outpatient CR and RCAP after AMI are very poor. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCAP, regional clinical alliance path.

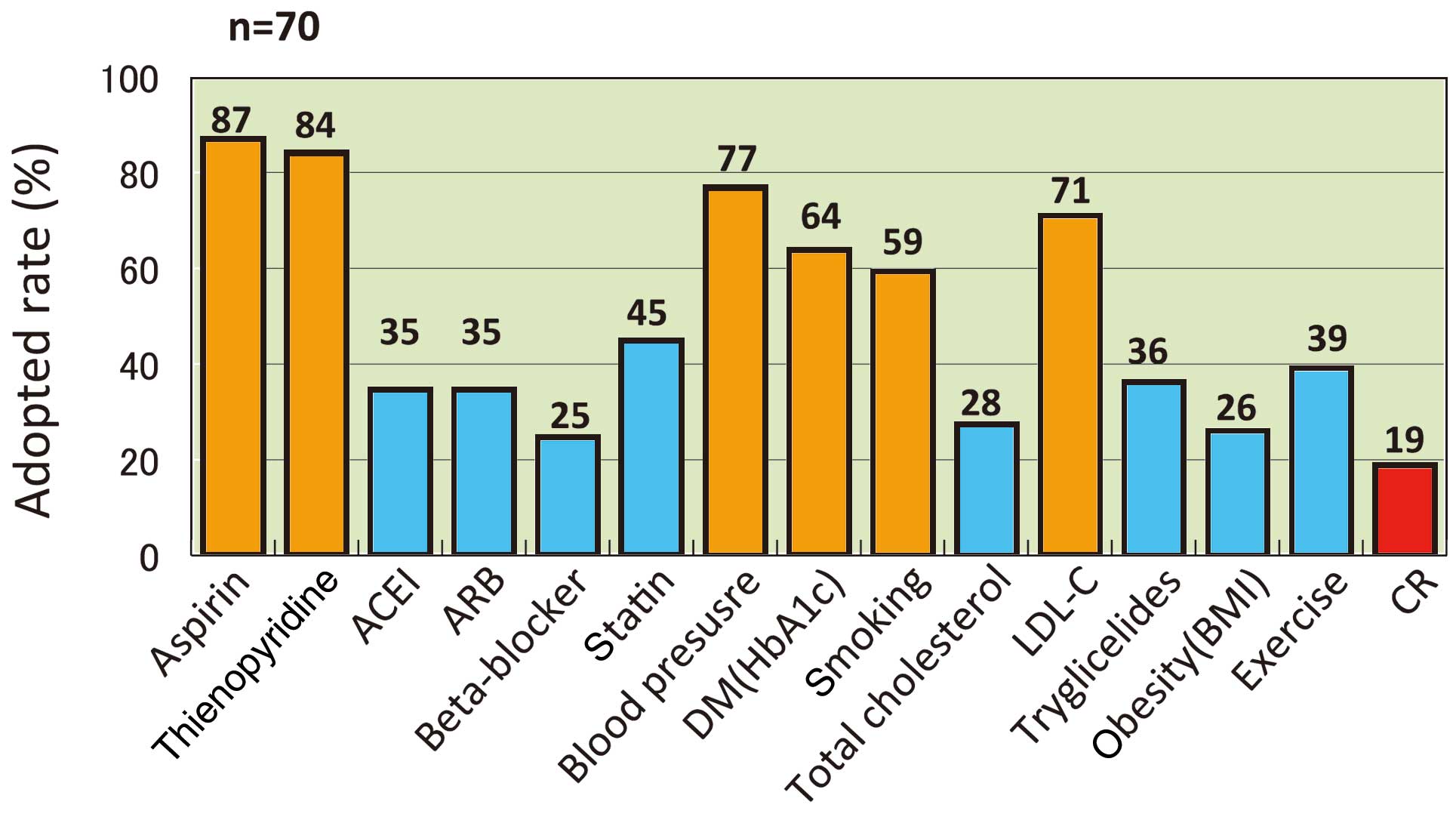

Components of RCAP were analyzed in the 70 hospitals that implemented it (Figure 2). For secondary prevention, modification of coronary risk factors such as blood pressure, HbA1c, smoking and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, were described in 59–77% of RCAP. However, exercise recommendations were made in only 39% of RCAP, and only 19% incorporated a CR program or recommended participation in CR.

Content of RCAP programs after acute myocardial infarction in 70 hospitals currently implementing post-acute care. Although antiplatelet medications and coronary risk factor amelioration were frequently adopted, “exercise” and “CR” are rarely adopted. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index; CR, cardiac rehabilitation; DM, diabetes mellitus; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; RCAP, regional clinical alliance path.

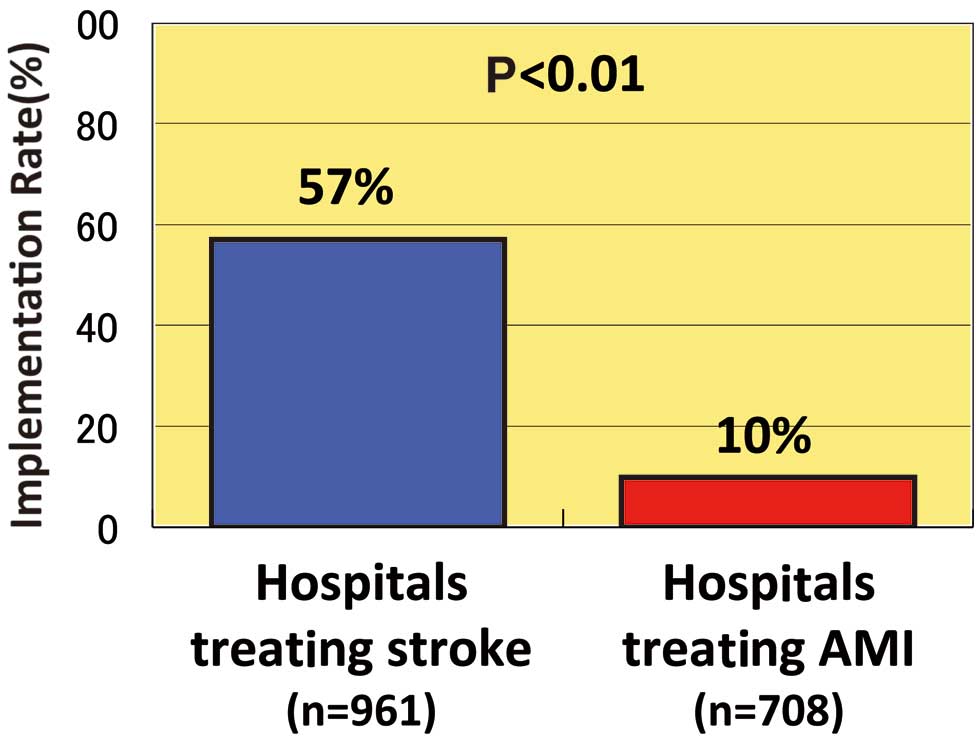

Implementation rates of RCAP in AMI and stroke hospitals are shown in Figure 3. The implementation rate of RCAP in hospitals treating AMI (70/708 hospitals, 10%) was significantly lower than that in hospitals treating stroke (548/961 hospitals, 57%, P<0.01).

Rate of implementation of regional clinical alliance path in hospitals treating acute myocardial infarction or stroke.

The comparison of RCAP hospitals (n=70) and non-RCAP hospitals (n=638) is summarized in Table 2. The numbers of total beds, cardiology beds, and cardiologists, and the annual volumes of hospitalized AMI patients, PCI procedures, cardiac surgeries, and CABGs were all greater in RCAP hospitals than in non-RCAP hospitals. The implementation rates of acute-phase CR, patient education programs, and exercise prescriptions based on CPX were also significantly higher in RCAP hospitals than in non-RCAP hospitals. These data showing higher volumes of medical procedures and services in RCAP hospitals may be attributable to the larger size of these hospitals compared with non-RCAP hospitals. However, both RCAP and non-RCAP hospitals showed equally high implementation rates of CAG, PCI, and emergency PCI, and conversely, equally low implementation rates of OPCR programs. Also, the length of hospital stay was similar between the 2 types of hospitals.

| RCAP (n=70) |

Non-RCAP (n=638) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of total beds | 501±261 | 406±236 | <0.01 |

| No. of cardiology beds | 46±36 | 39±23 | <0.05 |

| No. of cardiologist | 8.0±7.1 | 6.2±6.4 | <0.05 |

| Presence of cardiovascular surgery department | 70.0% | 52.8% | <0.01 |

| Implementing CAG | 97% | 93% | NS |

| Implementing PCI | 96% | 92% | NS |

| Implementing emergency PCI | 87% | 90% | NS |

| Presence of specialized CR room | 43.9% | 28.4% | <0.01 |

| Approved facility for CR | 42.4% | 28.2% | <0.05 |

| Annual no. of AMI patients | 86±62 | 56±50 | <0.001 |

| Annual no. of CAG | 795±631 | 534±572 | <0.001 |

| Annual no. of PCI | 285±231 | 191±201 | <0.001 |

| Annual no. of cardiac surgery | 83±142 | 49±298 | <0.01 |

| Annual no. of CABG | 32±41 | 22±37 | <0.001 |

| Average length of stay for AMI | 15.6±6.6 | 14.8±5.7 | NS |

| Acute-phase CR for AMI | 79.7% | 58.1% | <0.001 |

| Implementing patient education program | 38.6% | 22.6% | <0.005 |

| Implementing exercise prescription based on CPX | 35.7% | 22.1% | <0.05 |

| Implementing outpatient CR program | 24.3% | 16.9% | NS |

Values are mean±standard deviation. Abbreviations as in Table 1.

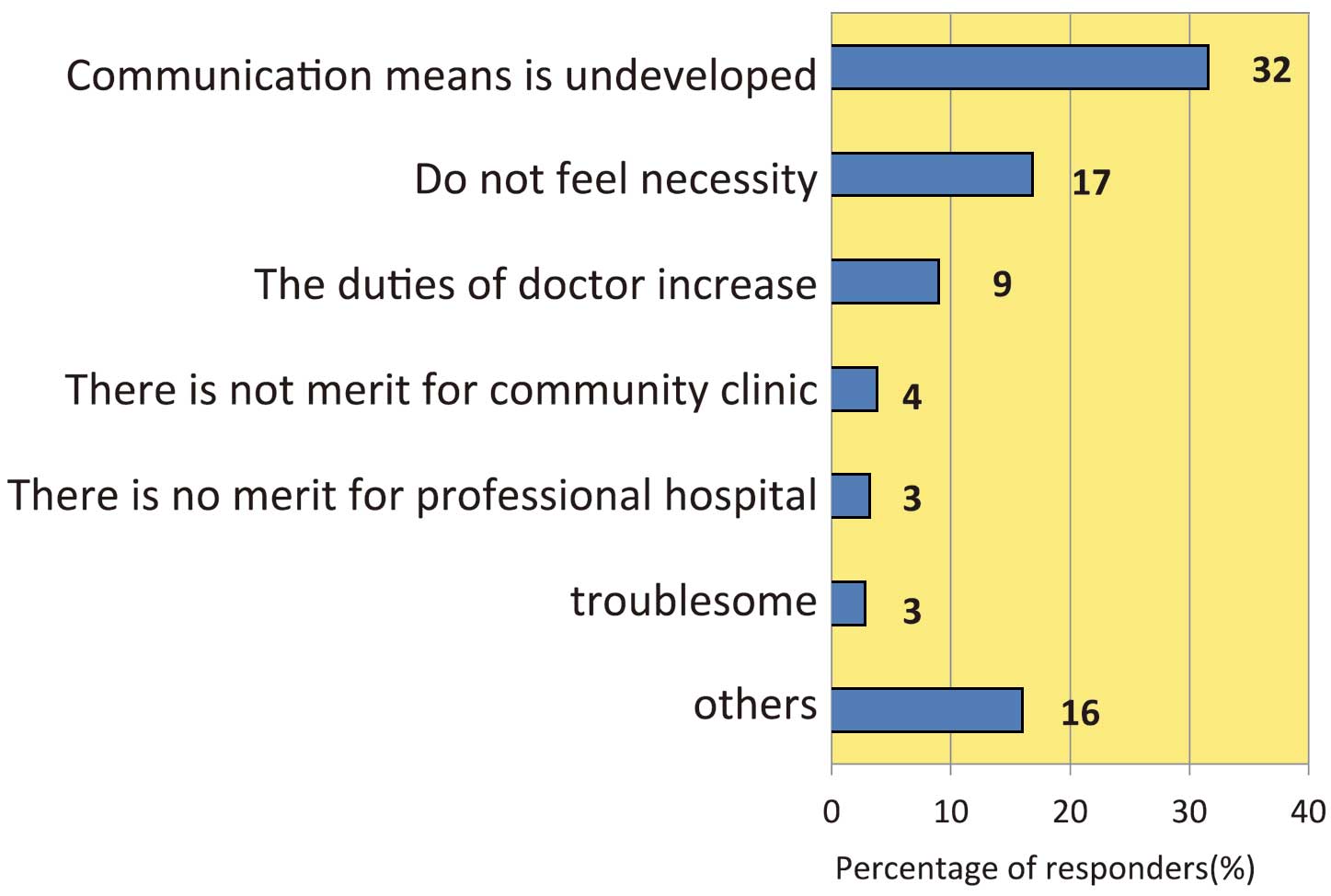

Reasons for non-implementation of CR are shown in Figure 4. When the 1st and 2nd reasons were combined, “Communication methods are undeveloped” and “Do not feel necessity” were common answers, provided by 31.6% (224) and 16% (119) of hospitals, respectively. “Increased duties for doctors” (9%, 64 hospitals) or just “Troublesome” (2.8%, 20 hospitals) were additional reasons. A total of 29% (203/708) of hospitals had plans to implement RCAP after AMI.

Non-implementation of regional clinical alliance path after acute myocardial infarction when the 1st and 2nd reasons are combined.

This is the first nationwide survey on the implementation of RCAP for AMI in Japan. There were 3 major findings. First, although acute-phase invasive procedures were implemented at very high rates in hospitals treating AMI, RCAP had a very low implementation rate of 10%, which was significantly lower than for stroke (57%). Second, the implementation rate of OPCR was remarkably low at 18%, and in the 70 currently operating RCAP programs, CR was included as part of RCAP in only 19%. Third, although patient education programs and exercise prescription based on CPX were implemented at a higher rate in RCAP hospitals than in non-RCAP hospitals, the implementation rate of OPCR was low in both.

Previous StudiesTashiro et al reported that in Fukushima prefecture the introduction of RCAP led to a concentration on specialized medical care by reducing the opportunity for outpatient visits in specialized hospitals, and also increased the patient unit price.4 They also reported that RCAP reduced the transportation time, labor and financial costs of patients for hospital visits, afforded patient relief by 2 attending physicians, and enabled the sharing of information and policies between hospitals and family physicians. Watanabe et al reported an increase in seamless medical care after the introduction of RCAP in 2009 in a rural area of Nagano prefecture, where the population density is low and more than 25% of hospitalized patients are 90 years of age or older.3 Attempts to implement RCAP after AMI have been reported in various areas of Japan, but no systematic surveys have been performed. In addition, although the quality of management after discharge is expected to improve following the introduction of RCAP, because of increased sharing of patient information and treatment goals between hospital physicians and family physicians, no reports on this topic exist.

Present StudyThe present study is not only the first national survey of RCAP after AMI, but it also evaluated the content of RCAP as well as CR status. Although national surveys of RCAP after stroke or femoral neck fracture have been performed,21,22 no surveys of RCAP after AMI have been reported thus far. The present study has therefore demonstrated for the first time that the implementation rate of RCAP after AMI has been very low, occurring in only 10% of Japanese hospitals treating AMI. In addition, CR was included in only 19% of currently operating RCAP programs, and the implementation of OPCR has been very poor in both RCAP and non-RCAP hospitals.

Reasons for Poor RCAP Implementation for AMIThere may be several reasons for the poor implementation of RCAP after AMI in comparison with stroke. The first is the difference between AMI and stroke in terms of the need for rehabilitation prior to returning to daily life. Although RCAP has been recognized as an information transmission tool when a patient is transferred to a convalescent rehabilitation hospital after stroke, RCAP is not considered to be necessary when patients are discharged directly to home after AMI. Second, because non-RCAP hospitals are relatively small, staff shortages may reduce the likelihood of RCAP implementation. However, RCAP in fact can reduce the workload of hospital physicians and would therefore be beneficial in such situations.4 Third, in Japan the PCI implementation rate is very high and the OPCR implementation rate is very low, regardless of hospital size, which suggests that there may be low awareness of the importance of OPCR and RCAP in the post-discharge management and secondary prevention after AMI.

Most reasons for not introducing RCAP can be resolved or are at least in part the product of misunderstandings. A method of transferring information between specialized hospitals and community clinics is necessary regardless of the presence or absence of RCAP, to enable cooperation between these institutions. Also, rather than increasing physician workload, RCAP reduces outpatient visits and thus allows specialized hospitals to concentrate on specialized medical care,4 resulting in a decreased overall workload in these hospitals.

We would speculate that the importance of RCAP will likely increase in the future for the following reasons: (1) the importance of secondary prevention has been recognized more than ever and management targets have been standardized by guidelines;12–16 (2) because treatment of cardiovascular disease has been increasingly specialized, mutual communication between specialized hospitals and community clinics will become even more necessary; and (3) populations are aging and patients have a larger number of comorbidities.

Reasons for Low Incorporation Rate of CR Into RCAPThis study showed that CR was infrequently adopted as part of RCAP programs, and the rate of OPCR implementation was low whether or not RCAP was established. According to other nationwide surveys in Japan, the rate of CR implementation itself remains low,17–19 which may be responsible for the low rate of adoption of CR in RCAP. In the hospitals with RCAP, despite the fact that they are generally large with considerable human resources, the implementation rate of OPCR was low. On the other hand, non-RCAP hospitals tend to be small to medium-sized with more limited human resources, and therefore may not be able to implement OPCR. If this is the case, these smaller hospitals should have more frequently implemented RCAP and entrusted post-discharge management and OPCR to community clinics and OPCR facilities, but the current status was not the case. Therefore, we speculate that the present results might show a lack of recognition of the importance of OPCR and RCAP. Patient management by RCAP and OPCR shares many similarities; for example, multidisciplinary staff are involved in secondary prevention/disease management programs and share the same treatment goals. Although the rate of OPCR implementation was still low (18%) at the time of the present investigation, it has nonetheless risen from the rate of 9% in the previous nationwide survey,17–19 leading us to expect that the adoption rates of OPCR will increase as its importance becomes more widely recognized.

Clinical ImplicationsCardiovascular event rates after discharge are still high, even though acute-phase mortality has declined and the length of hospital stay has been reduced. In fact, Okura et al8 reported that 34% of 2,736 Japanese AMI patients discharged alive died or were rehospitalized for cardiac reasons within 4.3 years, and Jernberg et al10 also reported that 34% of 97,254 patients surviving an AMI experienced cardiovascular events during a 4-year follow-up in Sweden. Because it has been established that long-term prognosis is improved by OPCR participation after discharge,23 high-quality management after discharge is now demanded. For example, Squires et al24 showed that OPCR can serve as a long-term disease management program in achieving and maintaining the secondary prevention goals in patients with coronary artery disease. Against this background, the present study showed that the dissemination of RCAP as a management tool after discharge has occurred very slowly in Japan, and the inclusion of OPCR as a component of RCAP is currently also very uncommon in Japan. In the future it will be important to more widely establish RCAP, not only as a system of patient referral, but also to increase OPCR participation, reduce coronary risk factors, improve quality of life, prevent heart failure, and improve long-term prognosis.

Study LimitationsBecause the present study was questionnaire-based for institutions, we could not confirm the accuracy of data on an individual patient-basis. In addition, caution should be taken in interpreting the present data, because not all patients would participate in RCAP and/or OPCR even in the hospitals implementing RCAP and/or OPCR. Finally, because the number of hospitals implementing RCAP and/or OPCR may have recently increased, the situation at present is expected to have improved from that shown in this study conducted in 2009.

This first nationwide survey of RCAP after AMI showed that in contrast to the wide adoption of acute-phase invasive treatment for AMI, both the implementation of RCAP for AMI and the incorporation of post-AMI OPCR into RCAP were very poor in Japan. Considering the rapid shortening of the length of hospital stay and the established benefits of OPCR, urgent efforts should be made to broaden the implementation of RCAP for AMI and incorporate OPCR into its approach.

Research for Cardiovascular Disease (20C-7) granted from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan.