2018 年 82 巻 2 号 p. 403-408

2018 年 82 巻 2 号 p. 403-408

Background: Current surgical outcomes of congenital heart surgery for patients with Down syndrome are unclear.

Methods and Results: Of 29,087 operations between 2008 and 2012 registered in the Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database (JCCVSD), 2,651 were carried out for patients with Down syndrome (9%). Of those, 5 major biventricular repair procedures [ventricular septal defect repair (n=752), atrioventricular septal defect repair (n=452), patent ductus arteriosus closure (n=184), atrial septal defect repair (n=167), tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) repair (n=108)], as well as 2 major single ventricular palliations [bidirectional Glenn (n=21) and Fontan operation (n=25)] were selected and their outcomes were compared. The 90-day and in-hospital mortality rates for all 5 major biventricular repair procedures and bidirectional Glenn were similarly low in patients with Down syndrome compared with patients without Down syndrome. On the other hand, mortality after Fontan operation in patients with Down syndrome was significantly higher than in patients without Down syndrome (42/1,558=2.7% vs. 3/25=12.0%, P=0.005).

Conclusions: Although intensive management of pulmonary hypertension is essential, analysis of the JCCVSD revealed favorable early prognostic outcomes after 5 major biventricular procedures and bidirectional Glenn in patients with Down syndrome. Indication of the Fontan operation for patients with Down syndrome should be carefully decided.

Congenital heart disease is reported to be associated in about half of all Down syndrome populations.1–3 The typical diagnosis is atrial septal defect (ASD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), or conotruncal anomaly such as atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and tetralogy of Fallot (TOF); functional single ventricle is sometimes seen. Surgical outcomes and life prognosis had been thought to be poor in patients with Down syndrome, but recent reports have shown that they were not inferior to those of patients without Down syndrome.1–6 It is worth noting that data concerning surgical outcomes for patients with a functional single ventricle and Down syndrome are limited.7–9

A clinical trial of noninvasive prenatal testing, which can detect trisomy 13, 18 and 21 (Down syndrome) from fetal cell-free DNA in maternal plasma, has been ongoing since April 2014.10 For Down syndrome, its sensitivity is 99.1% and specificity 99.9%.11 The current rate of termination of pregnancy for fetal Down syndrome is reported to be 93.8% in Japan.12

The Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database (JCCVSD) is a nationwide congenital heart surgery database, and was organized in 2008. Currently, 120 institutions participate and a total of 60,546 operations have been entered until August 2016.

The purpose of this study was to review the surgical outcomes of congenital heart surgery for patients with Down syndrome by analyzing the JCCVSD.

The Japanese Cardiovascular Surgery Database Organization Committee granted permission to access and analyze data collected in the JCCVSD with a waiver of informed consent.

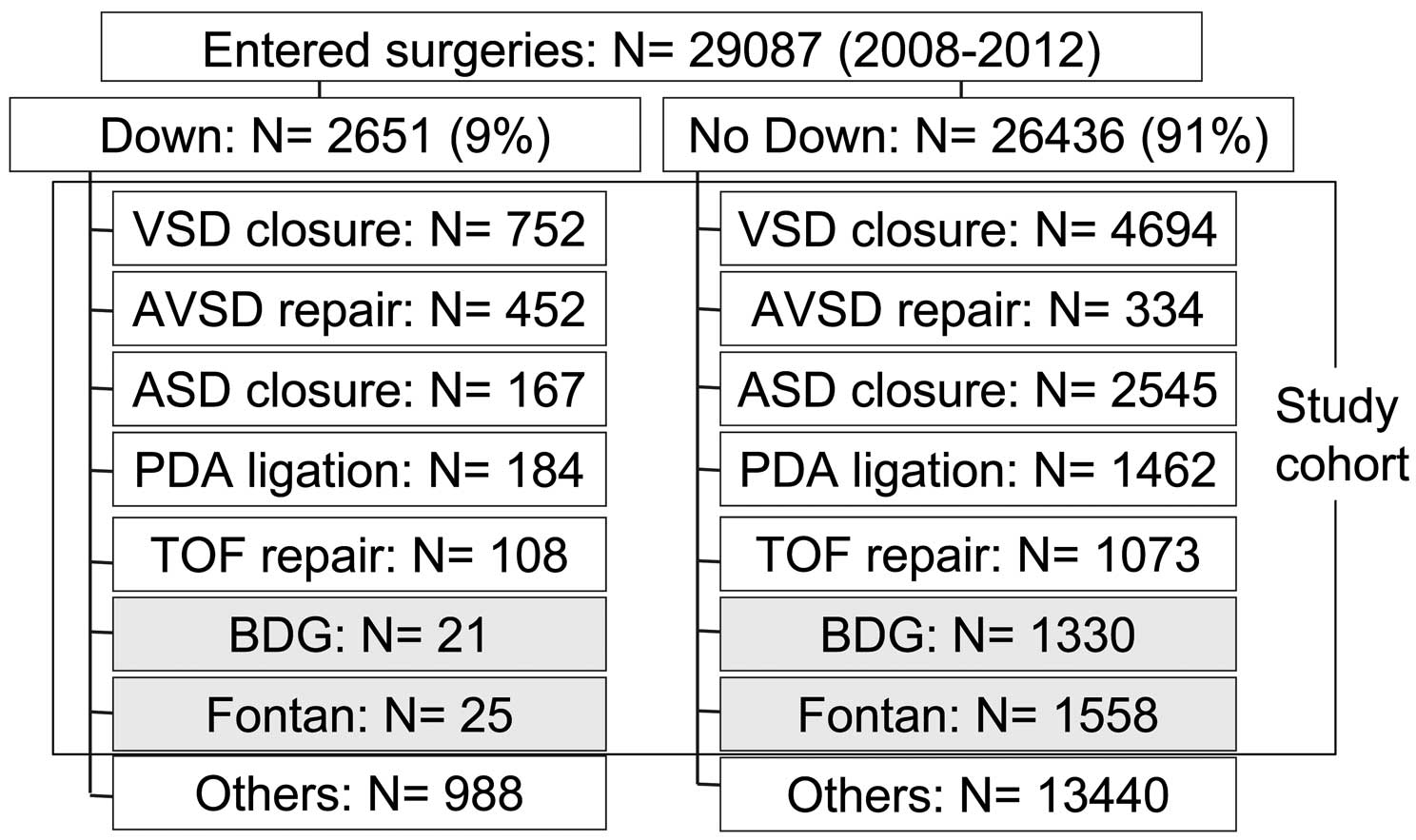

Between 2008 and 2012, 2,651 of 29,087 registered operations (9%) were carried out for patients with extracardiac anomaly: Down syndrome, or chromosomal abnormality: trisomy 21, or syndrome: Down syndrome (trisomy 21). Because 86.1% of all operations were performed for 5 major diagnose [VSD, AVSD, TOF, ASD and PDA: Table S1, Table 1], 5 definitive biventricular procedures [VSD closure (n=752), AVSD repair (n=452), ASD closure (n=167), PDA ligation (n=184), and TOF repair (n=108)] were selected. In addition, 2 major single-ventricle palliations [bidirectional Glenn (BDG) (n=21) and Fontan operation (n=25)] were also chosen [Table S2] and the patients’ outcomes were compared with those of patients without Down syndrome (Figure 1).

| Main diagnosis | Number of surgeries (%) |

|---|---|

| VSD | 891 (33.6) |

| AVSD | 863 (32.6) |

| TOF | 190 (7.2) |

| ASD | 173 (6.5) |

| PDA | 165 (6.3) |

| TOF/AVSD | 88 (3.3) |

| CoA, IAA | 78 (2.9) |

| DORV | 58 (2.2) |

| PA/VSD | 35 (1.3) |

| Single ventricle | 30 (1.1) |

| Unbalanced AVSD | 21 |

| Other | 9 |

| Others | 80 (3.0) |

| Total | 2,651 |

ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; CoA, coarctation of the aorta; DORV, double-outlet right ventricle; IAA, interrupted aortic arch; PA, pulmonary atresia; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

Determination of the study cohort selected from the Japan Congenital Cardiovascular Surgery Database. ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; BDG, bidirectional Glenn; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

For patients undergoing ASD repair, VSD repair, and AVSD repair, preparative pulmonary artery banding was more frequently performed in patients with Down syndrome (Table 2). For patients undergoing AVSD repair, repair of complete-form AVSD was more frequently observed in patients with Down syndrome (Down vs. non-Down: 387/452 (85.6%) vs. 116/334 (34.7%), P<0.001). The age at surgery was younger in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (0.8±1.4 years), AVSD repair (1.2±1.9 years), and ASD repair (2.1±4.2 years), so their weights at surgery were also less. Prevalence of calculated pulmonary vascular resistance [PVR] >4 WU/m2 by preoperative catheter examination was more common in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (31.1%), AVSD repair (28.3%), ASD repair (23.1%), and PDA closure (36.2%); therefore, preoperative medication and home oxygen therapy for pulmonary hypertension (PH) were more frequently required in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (3.3 and 2.8%), AVSD repair (6.8 and 5.8%), and ASD repair (9.8 and 6.6%).

| Procedure | Patient no. |

Female [n (%)] |

Age at op. (years, mean±SD) |

BW at op. (kg, mean±SD) |

Palliative PAB [n (%)] |

Preop. cath. [n (%)] |

PVR >4 [WU/m2, n (%)] |

Medication, PH [n (%)] |

HOT [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSD repair | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 4,694 | 2,180 (46.4) |

3.3±6.9 | 12.5±14.0 | 483 (10.3) |

3,343 (71.2) |

328 (9.8) |

28 (0.8) |

34 (0.7) |

| Down | 752 | 403 (53.6)* |

0.8±1.4* | 5.6±4.6* | 142 (18.9)* |

582 (77.4)* |

181 (31.1)* |

19 (3.3)* |

21 (2.8)* |

| AVSD repair | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 334 | 190 (56.9) |

6.7±13.8 | 15.8±17.2 | 68 (20.4) |

293 (87.7) |

24 (8.2) |

4 (1.4) |

9 (2.7) |

| Down | 452 | 230 (50.9) |

1.2±1.9* | 7.3±7.1* | 221 (48.9)* |

400 (88.5) |

113 (28.3)* |

27 (6.8)* |

26 (5.8)* |

| ASD repair | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 2,545 | 1,496 (58.8) |

13.9±18.5 | 26.8±18.3 | 88 (3.5) |

1,699 (66.8) |

30 (1.8) |

16 (0.9) |

16 (0.6) |

| Down | 167 | 73 (43.7)* |

2.1±4.2* | 9.4±9.8* | 13 (7.8)* |

143 (85.6)* |

33 (23.1)* |

14 (9.8)* |

11 (6.6)* |

| PDA closure | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 1,462 | 830 (56.8) |

0.8±5.0 | 3.4±6.7 | 150 (10.3) |

17 (11.3) |

2 (1.3) |

4 (0.3) |

|

| Down | 184 | 101 (54.9) |

0.5±0.9 | 4.6±5.2 | 58 (31.5)* |

21 (36.2)* |

2 (3.4) |

1 (0.5) |

|

| TOF repair | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 1,073 | 459 (42.8) |

2.1±5.6 | 9.8±8.6 | 1,003 (93.5) |

32 (3.2) |

13 (1.3) |

45 (4.2) |

|

| Down | 108 | 46 (42.6) |

2.6±6.1 | 10.0±10.5 | 101 (93.5) |

7 (7.0) |

1 (1.0) |

9 (8.3) |

|

| BDG | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 1,330 | 584 (43.9) |

1.7±4.6 | 8.2±8.0 | 1,267 (95.3) |

30 (2.4) |

134 (10.6) |

335 (25.2) |

|

| Down | 21 | 9 (42.9) |

1.9±1.7 | 7.6±3.8 | 18 (85.7) |

1 (5.6) |

3 (16.7) |

7 (33.3) |

|

| Fontan | |||||||||

| Non-Down | 1,558 | 712 (45.7) |

4.9±6.7 | 15.4±12.5 | 1,528 (98.1) |

23 (1.5) |

352 (23.0) |

428 (27.5) |

|

| Down | 25 | 6 (24.0)* |

4.9±2.6 | 13.4±3.8 | 22 (88.0)* |

0 (0.0) |

11 (50.0)* |

15 (60.0)* |

|

*P<0.05. BDG, bidirectional Glenn; BW, body weight; Cath., catheterization; HOT, home oxygen therapy; Op., operation; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; SD, standard deviation; WU, Wood units. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Fundamental diagnoses of patients undergoing single ventricular palliations are listed in Table S3. Of 25 enrolled patients with Down syndrome undergoing Fontan operation, 11 had previously undergone BDG during the study period.

For single ventricular palliation procedures, age and body weight at operation were not significantly different. Patients with Down syndrome undergoing Fontan operation more frequently required preoperative pulmonary vasodilators (50.0%) and home oxygen therapy (60.0%) for PH (Table 2).

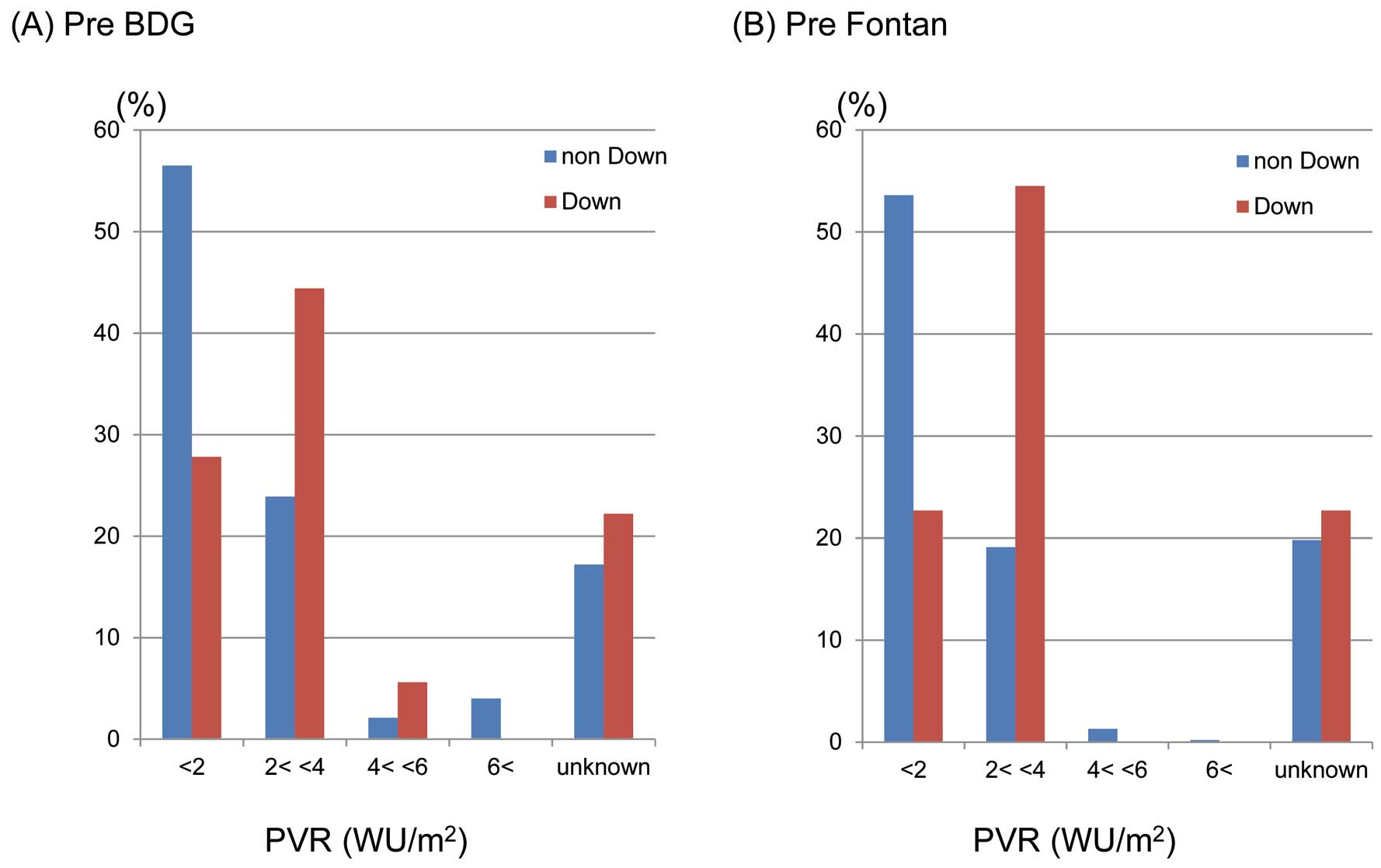

None of the patients with Down syndrome undergoing Fontan operation showed a PVR >4 WU/m2 at preoperative catheter examination, but PVR >2 WU/m2 seemed to be more frequently associated in patients with Down syndrome undergoing single ventricular palliation (Figure 2). The absolute PVR values could not be obtained from this database.

Distribution of pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) at (A) pre-bidirectional Glenn (BDG) and (B) pre-Fontan cardiac catheter examination in patients with and without Down syndrome. WU, Wood units.

At Fontan operation, fenestration was created in 288 of 1,558 patients (18.5%) in patients without Down syndrome and in 13 of 25 patients (52%) with Down syndrome (P<0.001). The size of the fenestration could not be obtained from this database.

Study Methods and Statistical AnalysisThis was a retrospective, multicenter study and the evaluated valuables were as follows. (1) Perioperative and in-hospital outcomes: cardiopulmonary bypass time, aortic cross-clamp time, and frequency of transfusion, use of nitric oxygen, PH crisis, mechanical ventilator support for >7 days and reintubation. (2) Outcomes at discharge and early after discharge: frequency of hospital stay >90 days, 90-day and in-hospital mortality rates, medication for PH, home oxygen therapy, and frequency of re-admission within 30 days.

The accuracy of the 90-day and in-hospital mortality data in JCCVSD has been confirmed.13,14 Statistical analysis was conducted using the Pearson’s chi-squared test and data were analyzed using JMP software version 10 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Cardiopulmonary bypass time was longer in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (110±47 min) and AVSD repair (185±76 min) (Table 3). Aortic cross-clamp time was longer in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (65±30 min). Transfusion was also more frequently required for patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (78.5%), AVSD repair (78.1%), and ASD repair (52.7%), but not PDA closure. Perioperative outcomes were not significantly different in patients undergoing single-ventricle palliation procedures.

| Procedure | CPB time (min, mean±SD) |

ACC time (min, mean±SD) |

Transfusion [n (%)] |

NO inhalation [n (%)] |

PH crisis [n (%)] |

Mechanical ventilation >7 days [n (%)] |

Reintubation [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSD repair | |||||||

| Non-Down | 100±48 | 59±32 | 2,475 (52.7) | 414 (8.8) | 8 (0.2) | 139 (3.1) | 89 (1.9) |

| Down | 110±47* | 65±30* | 590 (78.5)* | 153 (20.3)* | 8 (1.1)* | 50 (6.8)* | 28 (3.7)* |

| AVSD repair | |||||||

| Non-Down | 157±82 | 101±46 | 163 (48.8) | 33 (9.9) | 2 (0.6) | 20 (6.3) | 16 (4.8) |

| Down | 185±76* | 123±47 | 353 (78.1)* | 88 (19.5)* | 1 (0.2) | 58 (13.0)* | 35 (7.7)* |

| ASD repair | |||||||

| Non-Down | 64±34 | 28±24 | 260 (10.2) | 21 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (0.6) | 11 (0.4) |

| Down | 53±25 | 19±15 | 88 (52.7)* | 11 (6.6)* | 0 (0) | 3 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| PDA closure | |||||||

| Non-Down | 563 (38.5)* | 35 (2.4) | 2 (0.1) | 457 (32.8)* | 90 (6.2)* | ||

| Down | 51 (27.7) | 41 (2.5) | 0 (0) | 10 (5.8) | 6 (3.3) | ||

| TOF repair | |||||||

| Non-Down | 177±72 | 103±38 | 780 (72.7) | 53 (4.9) | 4 (0.4) | 57 (5.4) | 35 (3.3) |

| Down | 185±65 | 112±37 | 79 (73.1) | 13 (12.0)* | 1 (0.9) | 10 (9.3) | 8 (7.4)* |

| BDG | |||||||

| Non-Down | 132±75 | 974 (73.2) | 605 (45.5) | 4 (0.3) | 90 (7.0) | 86 (6.5) | |

| Down | 139±77 | 17 (81.0) | 15 (71.4)* | 0 (0) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | |

| Fontan | |||||||

| Non-Down | 135±84 | 1,068 (68.5) | 707 (45.4) | 1 (0.1) | 90 (6.0) | 94 (6.0) | |

| Down | 103±45 | 20 (80.0) | 20 (80.0)* | 0 (0) | 6 (24.0)* | 3 (12.0) | |

*P<0.05. ACC, aortic cross-clamping; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; NO, nitric oxide. Other abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

Nitric oxygen was more frequently required postoperatively in patients with Down syndrome undergoing all of the selected procedures except for PDA closure (Table 3). Postoperative PH crises rarely occurred, but were more frequent in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (1.1%). Requiring >7 days of mechanical ventilator support was comparatively more frequent in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD or AVSD repair, but not PDA closure. Reintubation was more frequently required in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair, AVSD repair, ASD repair, and TOF repair.

Outcomes at Discharge and Early After DischargePostoperative hospital stay >90 days was more frequently observed in patients with Down syndrome undergoing VSD repair (4.0%) and ASD repair (1.8%), but not PDA closure (Table 4).

| Procedure | Hospital stay, >90 days [n (%)] |

90 day and in-hospital mortality [n (%)] |

Medication, PH at discharge [n, (%)] |

HOT at discharge [n, (%)] |

Re-admission within 30 days [n, (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSD repair | |||||

| Non-Down | 103 (2.2) | 10 (0.2) | 268 (5.7) | 112 (2.4) | 79 (1.7) |

| Down | 30 (4.0)* | 4 (0.5) | 203 (27.0)* | 127 (16.9)* | 18 (2.4) |

| AVSD repair | |||||

| Non-Down | 20 (6.0) | 10 (3.0) | 19 (5.7) | 17 (5.1) | 10 (3.0) |

| Down | 33 (7.3) | 10 (2.2) | 101 (22.3)* | 52 (11.5)* | 22 (4.9) |

| ASD repair | |||||

| Non-Down | 7 (0.3) | 1 (0.04) | 30 (1.2) | 14 (0.6) | 43 (1.7) |

| Down | 3 (1.8)* | 1 (0.6)* | 36 (21.6)* | 25 (15.0)* | 6 (3.6) |

| PDA closure | |||||

| Non-Down | 518 (35.4)* | 42 (2.9) | 27 (1.8) | 88 (6.0) | 35 (2.4) |

| Down | 17 (9.2) | 5 (2.7) | 18 (9.8)* | 14 (7.6)* | 6 (3.3)* |

| TOF repair | |||||

| Non-Down | 37 (3.4) | 12 (1.1) | 30 (2.8) | 27 (2.5) | 30 (2.8) |

| Down | 7 (6.5) | 4 (0.5) | 16 (14.8)* | 9 (8.3)* | 7 (6.5) |

| BDG | |||||

| Non-Down | 197 (14.8) | 40 (3.0) | 351 (26.4) | 548 (41.2) | 64 (4.8) |

| Down | 4 (19.0) | 1 (4.8) | 12 (57.1)* | 9 (42.9) | 3 (14.3)* |

| Fontan | |||||

| Non-Down | 62 (4.0) | 42 (2.7) | 538 (34.5) | 479 (30.7) | 72 (4.6) |

| Down | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0)* | 17 (68.0)* | 16 (64.0)* | 5 (20.0)* |

*P<0.05. Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

For all 2,651 patients with Down syndrome, the combined 90-day and in-hospital mortality rate was 2.8%. For all of the 5 selected major biventricular repair procedures, the 90-day and in-hospital mortality rates were similarly low in patients with Down syndrome as compared with non-Down syndrome patients. The mortality rate in patients with Down syndrome undergoing ASD repair was statistically higher than in patients without Down syndrome, but only 1 patient died. On the other hand, the mortality rate in patients with Down syndrome undergoing Fontan operation was significantly higher than in patients without Down syndrome (3/25 (12.0%) vs. 42/1,558 (2.7%), P=0.005).

Medication for postoperative PH was more frequently required at discharge for patients with Down syndrome undergoing all 7 selected procedures. Postoperative home oxygen therapy was more frequently required in patients with Down syndrome undergoing all 5 selected biventricular procedures (7.6–16.9%), as well as the Fontan operation (64.0%). Re-admission within 30 days after discharge was more frequently seen in patients with Down syndrome undergoing PDA closure (3.3%), BDG (14.3%), and Fontan operation (20.0%).

This study especially focused on respiratory and prognostic outcomes in patients with Down syndrome undergoing 5 selected biventricular procedures and 2 single-ventricle palliations. For patients undergoing a biventricular procedure, approximately 30% of the patients with Down syndrome had preoperative PVR >4 WU/m2, and thus were more frequently treated with preoperative pulmonary vasodilator and home oxygen therapy. Postoperative courses were complicated; for example, 6–20% of patients undergoing any of the 5 biventricular procedures excepting PDA ligation required nitric oxygen inhalation to attenuate PH and to prevent a lethal PH crisis. Longer mechanical ventilator support and reintubation were frequently seen. However, PH crises were rarely seen and the 90-day and in-hospital mortality rates were satisfactorily low.

Outcomes after PDA closure seemed to present the opposite result, because patients without Down syndrome undergoing PDA closure included more extremely low birth weight infants with persistent fetal circulation, which is a known risk factor for PH, prolonged mechanical ventilator support and hospitalization.15

More frequently performed preparative pulmonary artery banding and younger age and smaller body weight at intracardiac repair in patients with Down syndrome undergoing ASD, VSD and AVSD repair indicated that patients with Down syndrome had large and complex intracardiac defects and were also complicated by more severe clinical conditions such as PH.

Although patients with Down syndrome and PH are reported to have a poorer response to nitric oxide inhalation,16 the importance of nitric oxide inhalation was also reported to be absolutely essential for the management of post-repair PH, even in patients with Down syndrome.17 Also, pulmonary vasodilator and home oxygen therapy at discharge were much more frequently required by patients with Down syndrome, which contributed to the present favorable early prognostic outcomes.

On the other hand, the early prognostic outcome was not favorable in patients with Down syndrome undergoing the Fontan operation. Although the small number of patients with Down syndrome was a limitation for statistical analysis, 3 of 25 patients (12.0%) died early after the Fontan operation. Reported operative mortality rates in patients with Down syndrome are 12.5% (1/8), 25% (1/4), and 35.3% (6/17),7–9 so the presented outcome was not inferior, but was still higher than in patients without Down syndrome (42/1,558=2.7%). All 3 Down syndrome patients who died after the Fontan operation were diagnosed as unbalanced AVSD. Although no preoperative risk factor was identified and the major cause of death was not revealed in the database, remaining with superior cavopulmonary shunt with leaving antegrade pulmonary blood flow may be an alternative to Fontan, because aggressive biventricular repair for patients with a borderline left ventricle rarely promises good early postoperative outcome or good long-term hemodynamic outcome.

Current development of prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal anomalies forces parents into important decision-making before childbirth. As a result, the number of babies born with Down syndrome is now decreasing. Against the background of this social trend, the presented objective and accurate outcomes of current congenital heart surgery for patients with Down syndrome would be meaningful information for parents and their caregivers.

Study LimitationsFirst, preoperative catheter examination was not routinely performed, as shown in Table 2, and PVR was calculated in approximately 60–90% of patients who underwent it. However, considering the setting of a retrospective multicenter study, the presented dataset is thought to be sufficient for statistical analysis. Second, previous palliative pulmonary artery banding was more frequently performed in patients with Down syndrome undergoing ASD repair, VSD repair and AVSD repair. When taking into account mortality during palliative operation to that during definitive surgery, the presented favorable early prognostic outcomes might pale in significance. However, severe PH was more frequently observed in patients with Down syndrome at pre-definitive surgery evaluation, so the presented outcomes are believed to accurately reflect the patients’ clinical features in the current surgical era.

Although intensive management of PH is essential, favorable early prognostic outcomes after 5 major biventricular repair procedures in patients with Down syndrome were confirmed by the analysis of JCCVSD. Indication of the Fontan operation for patients with Down syndrome should be carefully decided.

None.

Supplementary File 1

Table S1. Selected fundamental diagnoses from database

Table S2. Surgical procedure

Table S3. Fundamental diagnoses of patients undergoing single ventricular palliations

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0483