2018 年 82 巻 2 号 p. 361-368

2018 年 82 巻 2 号 p. 361-368

Background: The European Society of Cardiology recommends a risk-based antithrombotic strategy for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) based on CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. However, because it is unclear if that strategy can be generalized to Asians, we aimed to describe antithrombotic therapies among Japanese patients.

Methods and Results: Using a nationwide claims database in Japan, this retrospective cohort study identified AF patients who underwent PCI from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015. The primary outcome was utilization of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents before PCI, at discharge, and 6, 9, and 12 months after PCI. The secondary outcome was incidence of stroke after PCI. We identified 10,862 patients and 87.5% of them had high CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores. There were no significant differences in antithrombotic therapies across the risk strata. More than 30% of patients at high risk of thrombosis did not receive oral anticoagulant prescriptions at discharge. The hazard ratio of incidence of stroke in patients with prior stroke compared with patients without prior stroke was 9.09 (95% confidence interval 7.86–10.50, P<0.01).

Conclusions: Among Japanese AF patients who underwent PCI, prescriptions for antiplatelet agents were more common than those for anticoagulant agents. The majority of study participants were classified as high risk, suggesting a need for a new risk classification that reflects the risk profiles of Japanese patients.

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most common arrhythmia in the elderly, is often accompanied by vascular comorbidities.1–4 Approximately 20% of patients with AF undergo a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass graft.5 In addition to anticoagulant agents, patients with AF who undergo PCI receive antiplatelet agents such as aspirin and clopidogrel to prevent stent thrombosis,1,6 but the optimal combination and duration that balances the benefit of stent thrombosis prevention and the risk of bleeding remain controversial.

In a randomized clinical trial of 573 patients, the bleeding risk during the 1-year follow-up was higher with triple therapy (TT: an anticoagulant and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT)) than that with double therapy (DT: an anticoagulant and single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT)) without enhanced risks of vascular events.7,8 In the ISAR-TRIPLE Trial,9 which compared TT of different durations (6 months and 6 weeks), in AF patients undergoing interventions with drug-eluting stents (DES), there were no significant differences in cardiac death, myocardial infarction, definite stent thrombosis, and ischemic stroke.

At an individual level, a patient’s stroke and bleeding risks may be assessed by the CHA2DS2-VASc score10 and HAS-BLED score.11 The Joint Consensus Report of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recommends choosing an antithrombotic strategy based on risk assessment.1 In this recommendation, the duration of the initial DT or TT ranges from 4 weeks to 12 months based on a patient’s risks. The guidelines on PCI of the Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) state that the duration of discontinuation of both aspirin and thienopyridines should be as short as possible in patients with a high risk of bleeding.6 However, it is unclear whether the strategy recommended for European patients can be generalized to Asians because cardiovascular risks depend on ethnicity.12 Furthermore, the CREDO-Kyoto Registry Cohort-2 reported underuse of oral anticoagulant (OAC) for Japanese patients.13 We therefore aimed to identify prescription of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents among AF patients undergoing PCI using a claims database that universally covers health insurance in Japan.

This was a retrospective cohort study using the National Database of Health Insurance Claims and Specific Health Checkups of Japan (NDB), a nationwide claims database created and maintained by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry (MHLW) based on the Elderly Health Care Security Act.14 The NDB has held more than 90% of the health insurance claims for medical fees and dispensing fees for all insured people in Japan since April 2009. Data on regular health checks have been also collected since fiscal year (FY) 2008. In this study, we obtained NDB data from April 1, 2009 to March 31, 2015. The database covers all claims from all medical institutes in Japan but unique identifiers of institute were not available. According to a previous report of The Japanese Registry Of All cardiac and vascular Diseases (JROAD) at least 1,200 cardiovascular medicine/surgery institutes are included in the database.

Because the data are completely de-identified before being provided to researchers, this study was exempt from obtaining individual informed consent according to the Ethical Guidelines on Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and the MHLW. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kyoto University Graduate School and Faculty of Medicine (E2456).

Study ParticipantsWe identified AF patients who underwent PCI from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015 in Japan. The criteria for eligibility were ischemic heart disease (ICD-10 code: I20, I21, I22, I248, I249, I251, I252, I259) treatment with PCI, having AF (ICD-10 code: I48, I978) within 1 year before undergoing PCI, and prescription of anticoagulant agents (warfarin, apixaban, dabigatran, edoxaban and rivaroxaban) or antiplatelet agents (aspirin, clopidogrel, ticlopidine, cilostazol, alprostadil afadex, dipyridamole, sarpogrelate, prasugrel, icosapent ethyl, beraprost, limaprost and ozagrel) within 1 year before undergoing PCI. Edoxaban and prasugrel were approved in September 2014 and March 2014, respectively. All the other anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents had been approved by April 2013. Definitions of each disease according to whether it was (1) a solo ICD-10 code or a (2) solo medication/operation code or (3) a combination of an ICD-10 code and its medication/operation and diagnosis tests, information on ICD-10 codes used to identify each disease and each disease’s ATC code used to identify each prescription are shown in Tables S1–S3.

OutcomesThe primary outcome was utilization of anticoagulant agents and antiplatelet agents before PCI, at discharge, and 6, 9, and 12 months after PCI. The secondary outcome was incidence of stroke after PCI. Drug utilization was classified as SAPT, DAPT, DT, and TT. The list of ATC codes for each agent is provided in Table S1. We defined stroke as having both related disease name records and medical practice records of image diagnosis (computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)). The disease name codes included cerebral infarction (ICD-10 code: I63.x, I693), subarachnoid hemorrhage (I60.x), intracerebral hemorrhage (I610, I611, I613, I614, I615, I616, I619) and nontraumatic intracranial hemorrhage (I620, I629).

Risk StratificationRisks of thrombosis and bleeding for each patient were assessed by the modified CHA2DS2-VASc score (congestive heart failure, hypertension, age, diabetes mellitus, stroke, vascular disease, and sex) and the modified HAS-BLED score (hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke and thromboembolism, bleeding, age, drug consumption) based on claims records.1 The definitions and code lists are provided in Table S2 and Table S3. Patients were classified into 4 groups according to high (H) or low (L) thrombosis and bleeding risks before PCI: CV(L)-HAS(L), CHA2DS2-VASc <2 and HAS-BLED <3; CV(L)-HAS(H), CHA2DS2-VASc <2 and HAS-BLED ≥3; CV(H)-HAS(L), CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 and HAS-BLED <3; CV(H)-HAS(H), CHA2DS2-VASc ≥2 and HAS-BLED ≥3.

Statistical AnalysisData are represented as values and percentages and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR). Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test with CV(H)-HAS(H) as the reference. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the risks of stroke. We expressed the associations between risk stratification by CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED score or history of stroke and incidence of stroke as hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) estimated by Cox regression. All reported P-values were 2-sided, and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted by academic researchers (FO and ST) using SAS software version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

We initially identified 18,658 Japanese patients with AF who underwent PCI from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015 using claims records provided by the NDB (Figure 1). Among these, we further identified 10,862 patients who were prescribed anticoagulant agents or antiplatelet agents within 1 year before PCI. The average durations covered by the NDB before and after PCI treatment were 1,829 days (min: 28, max: 2,160) and 159 days (min: 0, max: 334), respectively.

Flowchart of a study of anticoagulant and antiplatelet prescription for patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in Japan.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 10,862 patients according to thrombosis and bleeding risks; 87.5% of the entire patient population were classified as CV(H)-HAS(H) with high thrombosis and bleeding risks. Compared with the other groups, patients in CV(H)-HAS(H) were older and had significantly more comorbidities: 97.5% had hypertension, 85.0% had heart failure, 41.3% had diabetes mellitus, 44.2% had a myocardial infarction, 9.0% had renal dysfunction, 14.5% had a history of acute coronary syndrome, and 35.2% had a stroke history. More than 80% of patients underwent PCI with a DES and there were no differences in the proportions of stents or DES employed.

| CV(L)-HAS(L)* (n=167) |

P value | CV(L)-HAS(H)† (n=17) |

P value | CV(H)-HAS(L)‡ (n=1,172) |

P value | CV(H)-HAS(H)§ (n=9,506) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, median (IQR) |

1 (1, 1) | <0.01 | 1 (1, 1) | <0.01 | 3 (2, 4) | <0.01 | 5 (4, 6) |

| HAS-BLED score, median (IQR) |

2 (1, 2) | <0.01 | 3 (3, 4) | <0.01 | 2 (2, 2) | <0.01 | 4 (3, 4) |

| Age 65–74 years | 26.9% | 0.02 | 52.9% | 0.15 | 17.9% | <0.01 | 36.0% |

| Age ≥75 years | 0.0% | 1.00 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 22.0% | <0.01 | 59.5% |

| Male | 98.8% | <0.01 | 100.0% | 1.00 | 87.9% | <0.01 | 73.6% |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 1.8% | <0.01 | 5.9% | 0.33 | 10.1% | <0.01 | 14.5% |

| Heart failure | 17.4% | <0.01 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 82.0% | <0.01 | 85.0% |

| Hypertension | 34.7% | <0.01 | 41.2% | <0.01 | 59.8% | <0.01 | 97.5% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3.0% | <0.01 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 40.8% | 0.74 | 41.3% |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 0.0% | 1.00 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 2.4% | <0.01 | 35.2% |

| Myocardial infarction | 5.4% | <0.01 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 46.4% | 0.14 | 44.2% |

| Renal dysfunction | 1.8% | <0.01 | 41.2% | <0.01 | 0.1% | <0.01 | 9.0% |

| Prior stroke | 0.0% | 1.00 | 5.9% | 0.03 | 2.4% | <0.01 | 36.2% |

| Bleeding | 0.0% | 1.00 | 5.9% | 0.95 | 0.0% | 1.00 | 5.5% |

| Anemia | 0.0% | 1.00 | 88.2% | <0.01 | 0.4% | <0.01 | 29.0% |

| Bleeding/anemia | 0.0% | 1.00 | 88.2% | <0.01 | 0.4% | <0.01 | 30.3% |

| Prescriptions of antiplatelet agents | 95.8% | <0.01 | 100.0% | 1.00 | 93.3% | <0.01 | 98.9% |

| Prescriptions of NSAIDS | 29.3% | <0.01 | 58.8% | 0.20 | 32.4% | <0.01 | 43.0% |

| Drug-eluting stent | 86.2% | 0.08 | 76.5% | 0.64 | 81.6% | 0.57 | 80.9% |

| Stent | 94.0% | 0.02 | 82.4% | 0.48 | 87.5% | 0.64 | 88.0% |

Data are n (%) unless stated otherwise. *CV(L)-HAS(L): patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc score and low HAS-BLED score; †CV(L)-HAS(H): patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc score and high HAS-BLED score; ‡CV(H)-HAS(L): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and low HAS-BLED score; §CV(H)-HAS(H): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and high HAS-BLED score. IQR, interquartile range; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2 is a comparison of regimens before PCI and at discharge between the CV(H)-HAS(L) and CV(H)-HAS(H) groups (comparison of all groups is shown in Table S4). Before PCI, in each subgroup some patients had not been prescribed anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet agents and the percentage of those patients was the lowest in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group. Approximately 15% of patients in each group received DAPT. The proportion of patients receiving DT increased as thrombosis and bleeding risks increased and approximately 22% of patients had DT at most in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group. Except for the CV (L)-HAS (H) group, approximately 25% of patients in each group had TT. Considering the types of anticoagulant agents, the proportion of patients with a combination of novel oral anticoagulant (NOAC) and DAPT in the CV(H)-HAS(H) was significant lower than in the CV(L)-HAS(L) and CV(H)-HAS(L) groups. On the other hand, the combination of warfarin and DAPT showed the opposite tendency. In general, there were no regimens specific to each group before PCI.

| Before PCI | At discharge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV(H)-HAS(L)* (n=1,172) |

CV(H)-HAS(H)† (n=9,506) |

P value | CV(H)-HAS(L)* (n=1,172) |

CV(H)-HAS(H)† (n=9,506) |

P value | |

| None | 9.6% | 6.6% | <0.01 | 5.2% | 1.2% | <0.01 |

| SAPT | 8.1% | 10.7% | 0.01 | 2.1% | 2.3% | 0.54 |

| DAPT | 21.0% | 15.1% | <0.01 | 30.6% | 27.3% | 0.02 |

| NOAC | 12.5% | 10.3% | 0.02 | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.09 |

| DT (NOAC and SAPT) | 9.0% | 9.3% | 0.70 | 3.2% | 2.6% | 0.20 |

| TT (NOAC and DAPT) | 14.9% | 10.1% | <0.01 | 31.9% | 28.1% | 0.01 |

| Warfarin | 7.5% | 10.1% | <0.01 | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.07 |

| DT (warfarin and SAPT) | 6.0% | 12.7% | <0.01 | 1.8% | 2.8% | 0.05 |

| TT (warfarin and DAPT) | 9.4% | 13.0% | <0.01 | 21.2% | 31.9% | <0.01 |

| Other | 2.0% | 2.1% | – | 2.6% | 3.2% | – |

Data are n (%) unless stated otherwise. *CV(H)-HAS(L): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and low HAS-BLED score; †CV(H)-HAS(H): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and high HAS-BLED score. DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DT, double therapy; NOAC, novel oral anticoagulant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy; TT, triple therapy.

At hospital discharge, the proportion of patients receiving the regimen described as “none” decreased in each subgroup and the highest number was 5.2% of the CV(H)-HAS(L) group. The result of 1.2% of the CV(H)-HAS(H) group was significantly lower than for the CV(H)-HAS(L) and the CV(L)-HAS(L) groups. The proportion of patients with DAPT largely increased nearly 2-fold in each group, ranging from 27.3% to 38.3% and the highest proportion in the CV(L)-HAS(L) group was significantly higher than the lowest proportion in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group. Approximately half of the patients received TT in each group. According to the types of anticoagulant agents in TT, the prescription tendency at discharge was similar to that before PCI treatment. In contrast, the proportion of patients receiving DT at discharge largely decreased, ranging from 0% to 5%. In general, DAPT and TT were most frequently given to each group at hospital discharge.

Table 3 shows results of a comparison of agents prescribed before PCI and at discharge between the CV(H)-HAS(L) and CV(H)-HAS(H) groups (comparison of all groups is shown in Table S5). Before PCI, at least half of the patients in each group had been prescribed warfarin or a NOAC and the proportion increased as thrombosis and bleeding risk increased. The proportion of patients given warfarin was significantly higher in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group than in the CV(L)-HAS(L) and CV(H)-HAS(L) groups, whereas the proportion of patients given a NOAC increased as thrombosis and bleeding risk decreased. In each group, approximately half of the patients were given aspirin and approximately 40% were given clopidogrel. There were no significant differences among groups for prescriptions of aspirin and clopidogrel.

| Before PCI | At discharge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV(H)-HAS(L)* (n=1,172) |

CV(H)-HAS(H)† (n=9,506) |

P value | CV(H)-HAS(L)* (n=1,172) |

CV(H)-HAS(H)† (n=9,506) |

P value | |

| Warfarin | 24.9% | 37.9% | <0.01 | 26.4% | 38.2% | <0.01 |

| NOACs | 38.4% | 31.9% | <0.01 | 38.5% | 34.2% | <0.01 |

| Apixaban | 11.5% | 10.2% | 0.15 | 13.4% | 14.0% | 0.60 |

| Dabigatran | 10.5% | 8.6% | 0.03 | 9.4% | 7.6% | 0.03 |

| Rivaroxaban | 17.3% | 13.8% | <0.01 | 16.6% | 14.1% | 0.03 |

| Edoxaban | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.47 | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.61 |

| Aspirin | 59.1% | 60.2% | 0.47 | 80.5% | 86.5% | <0.01 |

| Combination: aspirin/clopidogrel | 5.5% | 3.8% | <0.01 | 13.4% | 11.1% | 0.02 |

| Clopidogrel | 44.0% | 38.9% | <0.01 | 78.6% | 83.3% | <0.01 |

| Ticlopidine | 3.0% | 3.0% | 0.97 | 2.9% | 2.9% | 0.99 |

| Prasugrel | 1.3% | 0.8% | 0.12 | 6.6% | 8.5% | 0.03 |

| Cilostazol | 2.0% | 5.1% | <0.01 | 2.6% | 4.7% | <0.01 |

Data are n (%) unless stated otherwise. *CV(H)-HAS(L): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and low HAS-BLED score; †CV(H)-HAS(H): patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and high HAS-BLED score. Abbreviations as in Table 2.

At hospital discharge, the percentage of patients with warfarin and a NOAC in each subgroup did not greatly change after PCI. In contrast, the percentage of patients given antiplatelet agents such as aspirin and clopidogrel greatly increased to as high as 86.5% (maximum in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group). There were no significant differences between prescription of aspirin and clopdogrel among the subgroups.

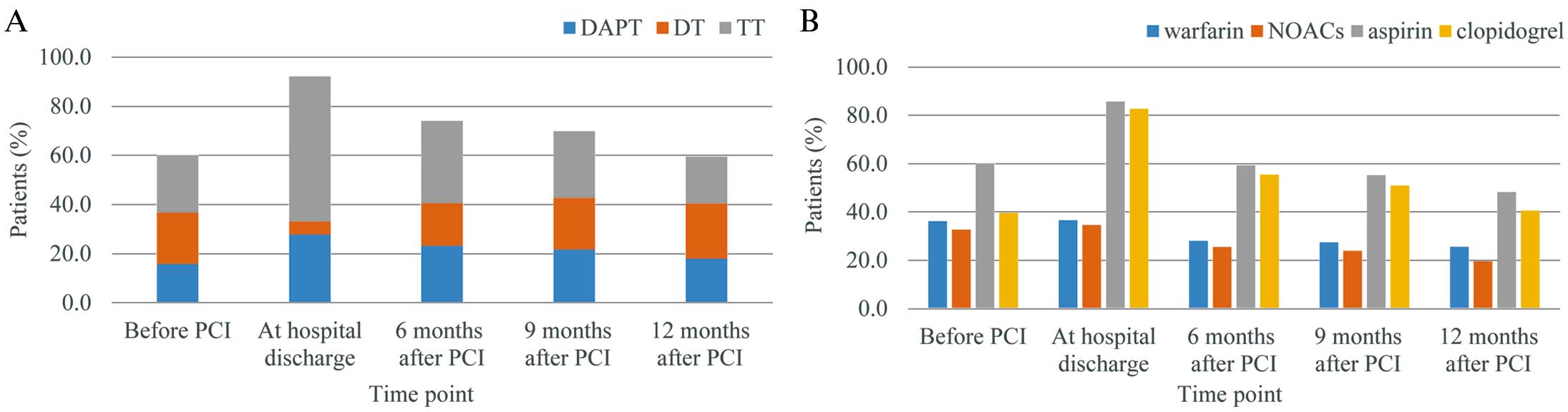

Figure 2A shows the transition of regimens for thrombosis before and after PCI in the entire population. Before PCI, DAPT, DT and TT were comparable, with proportions of 15.8%, 21.0% and 23.2%, respectively. At hospital discharge, TT was the most general followed by DAPT with proportions of DAPT, DT and TT being 27.8%, 5.3% and 59.1% respectively. However, at 6 months after PCI, TT greatly decreased to 33.5% and DT increased to 17.3%. At 9 months after PCI, the tendencies noted after PCI continued and finally, 12 months after PCI, the distribution of the regimens was similar to that before PCI (DAPT, DT, and TT were 18.0%, 22.5% and 19.0%, respectively).

Transition of treatment for thrombosis before and after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). (A) Transition of regimens (DAPT, DT, TT); (B) transition of prescriptions (warfarin, NOACs, aspirin, clopidgrel). DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DT, double therapy; NOAC, novel oral anticoagulant; TT, triple therapy.

Figure 2B shows the transition of prescriptions of warfarin, NOACs, aspirin, and clopidogrel over time. Before PCI, the proportion of prescriptions for warfarin and NOACs were comparable; warfarin and NOACs were prescribed for 36.2% and 32.7% of patients, respectively. Aspirin was used more than clopidogrel, with aspirin prescribed for 60.0% and clopidogrel in 39.6% of patients, respectively. At hospital discharge, prescriptions of warfarin and NOACs were hardly affected by PCI, remaining at 36.6% and 34.6%, respectively. Conversely, prescriptions of aspirin and clopidogrel greatly increased up to 85.7% and 82.7%, respectively. However, 6 months after PCI, prescriptions of aspirin and clopidogrel largely decreased approximately 60% and their prescription had been gradually decreasing by 12 months after PCI. The proportions of prescription of warfarin and clopidogrel slightly decreased and the tendency as antiplatelet agents had continued by 12 months after PCI. Finally, 12 months after PCI, the proportions of prescriptions of warfarin, NOACs, aspirin, and clopidogrel were 25.6%, 19.6%, 48.2%, and 40.6%, respectively, all of which were lower than before PCI.

Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for the incidence of stroke according to risk stratification by CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores and prior stroke history. Overall, 1,087 patients experienced stroke within 1 year after PCI. The hazard ratio in patients in the CV(H)-HAS(L) and CV(L)-HAS(L) groups compared with patients in the CV(H)-HAS(H) group was 0.16 (95% CI 0.16–0.33, P<0.01) and 0.10 (95% CI 0.03–0.42, P<0.01), respectively. The hazard ratio for patients with prior stroke compared with patients with no prior stroke was 9.09 (95% CI 7.86–10.50, P<0.01).

Kaplan-Meier curves for incidence of stroke. (A) Comparison among subgroups stratified by thrombosis and bleeding risk. Low-Low: patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc score and low Has-BLED score; Low-High: patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc score and high Has-BLED score; High-Low: patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and low Has-BLED score; High-High: patients with high CHA2DS2-VASc score and high Has-BLED score. (B) Comparison between subgroups with/without prior stroke. No prior stroke: patients without stroke history before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI); Prior stroke: patients with stroke history before PCI.

This retrospective cohort study of 10,862 AF patients selected from a database of nationwide health insurance claims in Japan described prescriptions for patients until 1 year after PCI. Use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents was classified as SAPT, DAPT, DT, and TT based on prescription records of warfarin, NOACs, aspirin, thienopyridines (clopidogrel, ticlopidine, prasugrel) and cilostazol. At discharge, more than 80% of patients received DAPT or TT, and more than 30% of patients were not treated with anticoagulant agents despite being at high risk of thrombosis. TT was prescribed to more than half of the patients at discharge and was decreased to half that proportion after 6 months, but was continued at 12 months in nearly 20% of patients. The incidence rate of stroke was increased by 10-fold among patients with a stroke history, which accounted for one-third of patients, suggesting a possibility of further risk stratification.

Based on a previous report on the prevalence of patients undergoing PCI in Japan (253,370 patients), the prevalence of patients with AF requiring antithrombotic therapy in Japan is estimated to be 7.4% among patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) who need PCI. Among the study population of 10,862 patients, approximately 60% were ≥75 years and at high risk of thrombosis and bleeding. The patients in this study were therefore slightly older than patients in previous studies in Japan13 and other countries.15,16 Prevalence of acute coronary syndrome was only 14% (Table 1). The remaining patients were considered to have stable CAD, presumably because of the frequency of PCI among Japanese patients with stable CAD.

The consensus report1 and ESC guidelines2 recommend that TT should be given for 4 weeks or 1 month, respectively, after PCI in patients at higher risk of thrombosis and bleeding, mainly because DT is associated with a lower rate of bleeding without an increase in the rate of thrombotic events.7,8 In the current study in Japan, however, nearly 40% of patients had continued TT or DAPT for 12 months (Figure 2). A previous study of 371 patients with AF who underwent stent implantation in Europe also found overuse of antiplatelet agents.17 The JCS guidelines also recommend that TT should be given for the shortest possible time,6 but the duration of TT is not indicated.6 A clear statement on the duration of TT would contribute to adherence to the guidelines.

It is surprising that more than 30% of AF patients at high risk of thrombosis did not receive anticoagulant therapy before PCI or at discharge. However, a similar evidence-practice gap was also reported in previous studies in Japan13 and Europe.17 In the CREDO-Kyoto Registry Cohort-2, more than half of patients did not receive anticoagulant therapy and the type of AF, such as persistent/permanent or paroxysmal, was associated with the use of anticoagulant agents.13 In the study in Europe that assessed adherence to antithrombotic therapy as recommended by the ESC guidelines,17 the rate of anticoagulant therapy at discharge was approximately 30%, and age >75 years, CHA2DS2-VASc score of ≥2, and use of OACs before stent implantation were associated with underuse. Our study confirmed the problem of OAC underuse previously reported using a nationwide database of health insurance claims in Japan.

The ESC,2 AHA/ACC/HRS,3 and JCS4 guidelines all recommend risk-based antithrombotic therapy for patients with AF. However, the present study revealed that prescription of anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents was similar across risk strata at hospital discharge (Tables 2,3). A possible reason for the lack of clear differences is that most patients in Japan are older than 70 years and are classified as being at high risk of thrombosis and bleeding. An important finding in this study is that more than 30% of patients had experienced stroke prior to PCI and had a 10-fold increased risk of stroke relative to those without prior stroke (Figure 3). As for predicting bleeding, a prospective study of 929 patients with AF who underwent PCI revealed that the HAS-BLED score was useless for high-risk populations around 75 years of age.18 The CHA2DS2-VASc score and HAS-BLED score are often binarized at some cutoff values,18,19 but careful consideration of the cutoff values is necessary to avoid ceiling effects. Our findings indicated the importance of treatment after stroke for secondary prevention, and higher cutoff values or further classification of patients with CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥2 or HAS-BLED score ≥3 may contribute to more accurate risk assessment when these scores are applied to populations at a high risk of stroke.

Study LimitationsFirst, the NDB did not include approximately 10% of claims data because some medical institutes had not introduced an electronic claims system. Actually, approximately 10% of clinics used paper claims systems, whereas almost all hospitals had already introduced electronic claims systems. Moreover, it was reported that in Japan there is a difference in prescription of anticoagulant agents between clinics and general hospitals: underuse in clinics20 and overuse in general hospitals.21 Therefore, the difference in coverage of electronic claims between clinics and hospitals may have affected the primary outcomes in this study, resulting in overestimation of the frequency of patients with prescription of anticoagulant agents. Second, the record linkage rate in the NDB is not 100% for technical reasons mainly related to ID.14 In the current study, we tried to link monthly claims records within individuals, but it is possible there were some unlinked records. However, the record linkage rate within the health claims database is much higher than that across the health claims database and errors in identifiers used in this study were not systematic. On the other hand, only 10% of patients in this study were followed up at 12 months, mainly because of a limited period of PCI covered by the dataset we obtained. Taken together, the influence of failure in record linkage on the results was small, but the 6–12-month data may have been subject to bias caused by losses to follow-up. Third, in the risk assessment, we modified the original versions of the CHA2DS2-VASc score and HAS-BLED score because clinical information was not available in the NDB. Specifically, the labile international normalized ratio and alcohol abuse were not included in the modified HAS-BLED score. Thus, it is possible that the modified scores underestimated the true risks of individual patients. Most of the patients in this study were, however, at high risk of thrombosis and bleeding despite potential underestimation. Thus, classification based on the true risks of individual patients seems to result in a slightly higher proportion of those at high risk of thrombosis and bleeding. Therefore, risk classification based on the original/modified CHA2DS2-VASc score and HAS-BLED score did not seem to make a difference in the primary outcomes of this study. Fourth, the proportions of prescriptions may have been underestimated for several reasons. For example, it was difficult in the claims records to distinguish patients who were not actually treated from those who did not visit the hospitals. Furthermore, it was possible that patients were admitted to the hospitals with their daily medications that had been prescribed while in other institutes previously, and such medications were not recorded in the claims databases. Fifth, identification of stroke based on claims data may not be accurate. However, a validation study of stroke using a Japanese healthcare claims database showed that the positive predictive values (PPVs) of the definition of stroke and intracranial bleeding using ICD-10 were relatively high at 74.0% and 85.0%, respectively.22 A systematic review of validation studies of cerebrovascular accident also reported that PPV of some definitions of stroke by ICD was over 80%.23 In our study, we used an algorithm using not only ICD-10 but also records of imaging such as CT and MRI, which are usually required for definitive diagnosis of stroke.

In conclusion, among AF patients undergoing PCI in Japan, prescription for antiplatelet agents was common after PCI. In contrast, more than 30% of AF patients with high thrombosis risk did not receive OAC prescriptions at discharge. TT was prescribed to more than half of patients at discharge but decreased by half after 6 months. The majority of study subjects were classified as high risk according to modified CHA2DS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scores, suggesting a need for a new risk classification that reflects the risk profiles of Japanese patients.

This work was financially supported by the Kyoto University Global Frontier Project for Young Professionals: the John Mung Program.

K.K. reports lecture fees from Eisai Co., Ltd., DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY, LIMITED, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., Novartis Pharma K.K., Pfizer Japan Inc. and Sanofi K.K., research grants from Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd. and Novartis Pharma K.K., and payment as an advisor from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., outside this manuscript; F.O. became an employee of Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., after completion of the study; S.T.’s wife had engaged in a research project of Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd.; The other authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Supplementary File 1

Table S1. Definitions of conditions based on disease, medication/operation and diagnosis information

Table S2. International statistical classification of disease 10th revision codes used to identify diseases

Table S3. Anatomical therapeutic chemical codes used to identify prescriptions

Table S4. Comparison of regimens before and after PCI according to thrombosis and bleeding risk

Table S5. Comparison of prescriptions before and after PCI according to thrombosis and bleeding risk

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0547