Abstract

Background:

Patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases. However, little is known regarding the risk of ischemic stroke in HIV-infected individuals with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Methods and Results:

From the Korean National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2016, we analyzed 962,116 patients with prevalent non-valvular AF aged ≥18 years. The overall HIV prevalence in AF patients was 0.17% (1,678 of 962,116). Oral anticoagulant (OAC)-naïve non-valvular AF (NVAF) patients with HIV had increased risks of ischemic stroke/systemic embolism (SE) [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 1.37; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.21–1.54], and major bleeding (adjusted HR 1.29; 95% CI, 1.15–1.46), compared with those without HIV. The incidence of ischemic stroke/SE in NVAF patients with HIV without any risk factors was similar to that of those without HIV at intermediate risk (i.e., male CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1) (2.04 vs. 2.18 events per 100 person-years). However, the use of OACs in AF patients with HIV was suboptimal, being only 8.9% at the time of AF diagnosis and 31.8% throughout the study period.

Conclusions:

The risks of ischemic stroke/SE and major bleeding were significantly higher in HIV-infected patients compared with non-HIV-infected patients with AF. Despite this, the actual use of OACs among AF patients with HIV was suboptimal.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia and is associated with a 5-fold increase in stroke risk. Therefore, stroke prevention is the most important management consideration for patients with AF.1–4

This is of particular concern in the HIV population because studies have shown not only a greater burden of cardiac arrhythmias, but also a higher prevalence of cerebrovascular events among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).5–7

The HIV pandemic continues to be a major public health problem.8

As early and effective antiretroviral therapy (ART) has become more widespread, HIV has transitioned from a progressive, fatal disease to a chronic, manageable disease marked by elevated risk of chronic comorbid diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD).9

HIV-infected individuals have been reported to have an increased CVD risk, with multiple studies demonstrating a 1.5–2-fold increase in the risk of stroke or myocardial infarction compared with non-HIV-infected individuals.10,11

In US national data, over a median follow-up of 6.8 years, 2.6% HIV patients developed AF.12

Another study reported that there were 2.0% confirmed AF/atrial flutter (AFL) cases and 1.57% AF/AFL among uninfected controls.13

Low CD4 counts (<200 cells/mm3) were also associated with elevated incidence and prevalence of AF among people living with HIV.12,13

Moreover, traditional AF risk factors, including increased age, white race, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, alcoholism, proteinuria, and reduced kidney function, were also strongly and independently associated with increased AF risk in the HIV setting.12

However, the risk of stroke or systemic embolism (SE) and major bleeding in HIV-infected patients with AF has not been evaluated. The aim of the current study was to assess the magnitude of increase in stroke and major bleeding risk in AF patients with associated HIV compared with AF patients without HIV.

Methods

This study was based on the national health claims database established by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of the Republic of Korea.1–4,14

The NHIS is the single insurer managed by the Korean government, and covers the entire Korean population. The following data are provided: sociodemographic information, individuals’ use of inpatient and outpatient services, pharmacy dispensing claims, and mortality data. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System (4-2016-0179), and informed consent was waived.

Study Population

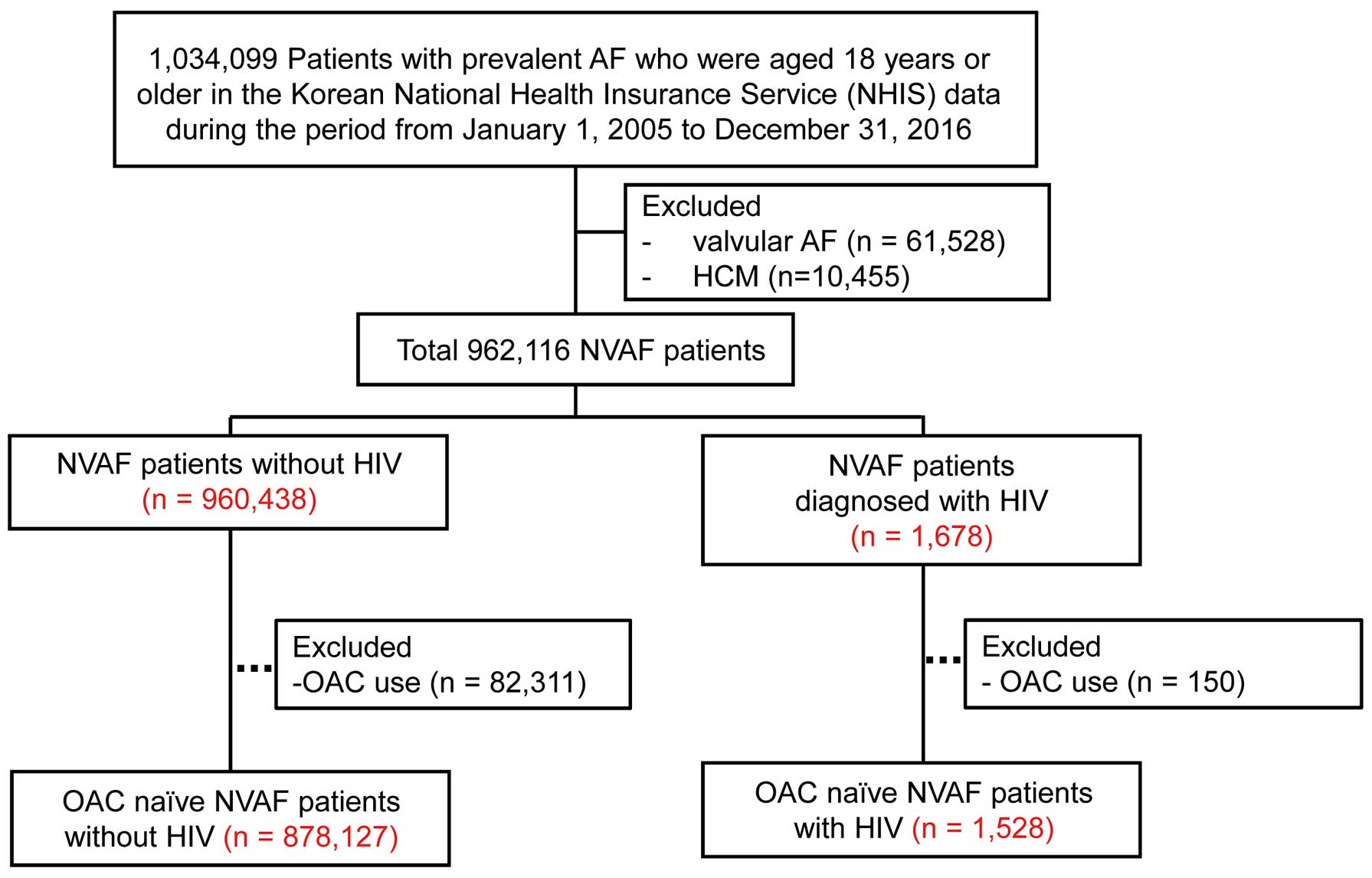

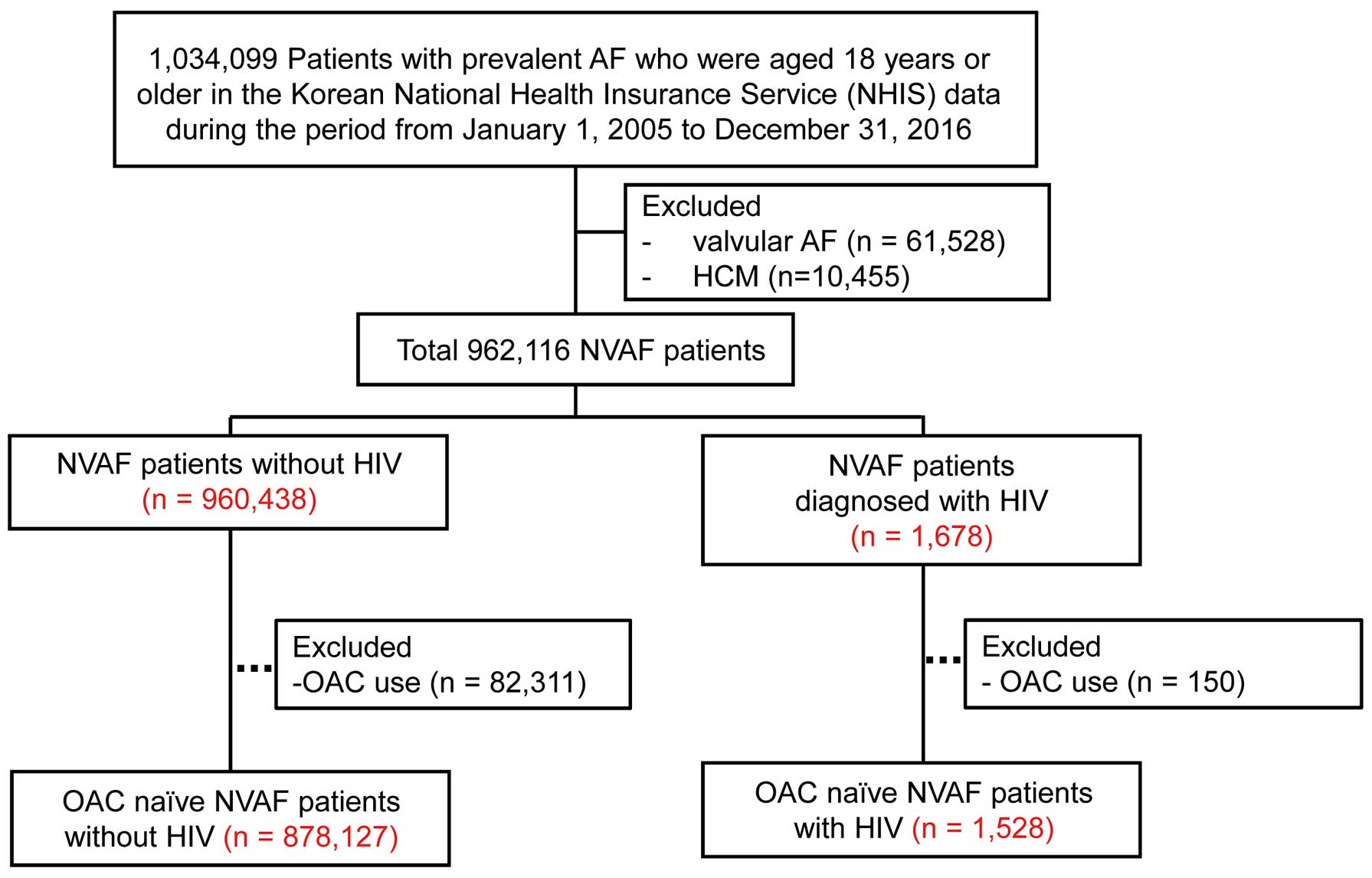

In the Korean NHIS data from January 1, 2005 to December 31, 2016, 1,034,099 patients aged 18 years or older with prevalent AF were identified. Patients with valvular AF, with a diagnosis of mitral valve stenosis and prosthetic valve disease were excluded (n=61,528). Because of their high risk of stroke,15

NVAF patients diagnosed with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) were also excluded (n=10,455). Among the remaining 962,116 patients with prevalent non-valvular AF, the prevalence of HIV was evaluated. Estimated timing from HIV infection to diagnosis has been reported to occur at a median of 4 years in Asians,16

so only patients diagnosed with HIV before AF diagnosis or within 4 years after AF diagnosis were considered to have HIV infection at the time of AF diagnosis. To assess the magnitude of increase in stroke risk in AF patients with HIV, HIV patients with oral anticoagulant (OAC) use (n=150) and non-HIV subjects with OAC use (n=82,311) at baseline were excluded. Finally, stroke stratification was analyzed in the remaining 879,655 OAC-naïve patients (Figure 1).

AF was diagnosed using the following International Classification of Disease 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes: I48 (AF and AFL), I48.0 (AF), and I48.1 (AFL). Moreover, to ensure diagnostic accuracy, patients were defined as having AF only when they were given AF as a discharge diagnosis or when this diagnosis was confirmed more than twice in the outpatient department. The diagnosis of AF has been validated in the NHIS database, with a positive predictive value of 94.1%.1–4,14,15

Patients with a diagnosis of HIV were identified using the ICD-10 codes (B20–B24).

In Korea, HIV-infected patients are registered in the national registry for rare diseases and can receive large medical expense reductions. Therefore, the HIV diagnostic code entry is very strictly controlled. To evaluate the accuracy of our definition of HIV, we conducted a validation study in 1,034 patients with the ICD-10 codes (B20–B24). The patients’ medical records and laboratory test results were reviewed by 2 physicians (P.-S.Y. and B.J.). Patients were ascertained to have HIV infection if the patient had a positive HIV antibody test confirmed by a second HIV antibody test relying on different antigens, and/or a positive virological test for HIV confirmed by a second virological test obtained from a separate determination.17

The positive predictive value was 97.3%.

Baseline Comorbidities and Medications

Baseline comorbidities were defined using the medical claims data according to ICD-10 codes and prescription medication use. The definitions of comorbidities and main diagnoses given during hospitalization are presented in

Supplementary Table 1.3,4,18

The presence of comorbidities was assessed at the time of AF diagnosis.

To evaluate the effect of OACs on primary prevention of stroke, we identified 1,201 patients with HIV and NVAF without a history of ischemic stroke or intracranial hemorrhage (320 OAC users, 881 OAC non-users). The cardiovascular outcomes of the OAC users who were enrolled at the date of OAC initiation were compared with those of the OAC non-users.

Exposure to ART was defined if ≥1 antiretroviral medication (nucleoside analog reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors or fusion inhibitors) was prescribed for >30 days. The cardiovascular outcomes of ART users who were enrolled at the date of ART initiation were compared with those of ART non-users.

Outcome Events

The primary endpoint was ischemic stroke/SE during the follow-up period. Any diagnosis of ischemic stroke with concomitant brain imaging studies, including computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, was defined as incident ischemic stroke. The accuracy of the diagnosis of ischemic stroke in the NHIS claims data has been validated.3,4,18

Secondary outcome events were the occurrence of ischemic stroke, major bleeding, gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial bleeding, and acute myocardial infarction. Major bleeding was defined as gastrointestinal bleeding or cerebral hemorrhage episode that required hospital admission and/or a blood transfusion.

Stroke and Bleeding Risk Stratification

The incidence rates of the thromboembolic endpoints according to the CHA2DS2-VASc (Congestive heart failure, Hypertension, Age ≥75 (doubled), Diabetes mellitus, prior Stroke or transient ischemic attack (doubled), Vascular disease, Age 65–74, female) score are presented as events per 100 person-years. The incidence rates for bleeding events are presented as events per 100 person-years according to the modified HAS-BLED scores [Hypertension, Abnormal renal function, abnormal liver function, history of ischemic Stroke, history of previous Bleeding, Elderly status (age >65 years), and concomitant Drugs (antiplatelet usage)]. Labile international normalized ratio and alcohol consumption were left out because these data were unavailable in the NHIS-NSC database. Exposure to antiplatelet usage was defined only if prescriptions were filled for >3 months.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±standard deviation, and categorical variables are reported as number of patients (percentage). The cumulative incidence of outcomes and differences according to CHA2DS2-VASc score were estimated by Fine and Gray regression to account for the competing risk of death. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to investigate the association between comorbidities and the incidence of endpoints, and a multivariate-adjusted analysis was performed after adjusting for all clinically significant variables including age, sex, hypertension, previous transient ischemic attack/ischemic stroke, previous hemorrhagic stroke, previous vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, history of malignant neoplasm, chronic kidney disease (CKD), dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and medications.

In order to quantify the predictive value of the CHA2DS2-VASc score for ischemic stroke and the composite thromboembolism endpoint during the follow-up period, we calculated the c-statistic and tested the hypothesis that these schemes performed significantly better than chance (indicated by a c-statistic ≥0.5). All tests were two-tailed, with P<0.05 considered to be significant. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and SPSS version 23.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The overall prevalence of HIV in the NVAF patients was 0.17% (1,678 of 962,116). Their baseline characteristics, with or without HIV, are presented in

Table 1. NVAF patients with HIV were younger than those without HIV (63.0±14.8 vs. 65.0±15.0 years, P<0.001). NVAF patients with HIV had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores (P<0.001) and more comorbidities than those without HIV (all P<0.001). ART was initiated in 11.5% (98/851) at the time of enrollment in AF patients diagnosed with HIV and 12.2% (187/1,528) during the whole follow-up period.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of NVAF Patients With and Without HIV

| |

Total |

OAC naїve |

Without HIV

(n=960,438) |

HIV

(n=1,678) |

P value |

Without HIV

(n=878,127) |

HIV

(n=1,528) |

P value |

| Age, years |

65.0±15.0 |

63.0±14.8 |

<0.001 |

64.8±15.2 |

62.7±15.0 |

<0.001 |

| <65 |

408,956 (42.6) |

818 (48.7) |

<0.001 |

380,045 (43.3) |

764 (50.0) |

<0.001 |

| 65–74 |

270,196 (28.1) |

469 (27.9) |

0.673 |

241,303 (27.5) |

412 (27.0) |

0.478 |

| ≥75 |

281,286 (29.3) |

391 (23.3) |

<0.001 |

256,779 (29.2) |

352 (23.0) |

<0.001 |

| Men |

511,401 (53.2) |

1,038 (61.9) |

<0.001 |

464,185 (52.9) |

946 (61.9) |

<0.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score |

3.19±2.12 |

3.41±2.24 |

<0.001 |

3.10±2.11 |

3.32±2.25 |

<0.001 |

| HAS-BLED score |

2.33±1.46 |

2.77±1.63 |

<0.001 |

2.27±1.46 |

2.71±1.64 |

<0.001 |

| Previous TIA |

71,004 (7.4) |

190 (11.3) |

<0.001 |

62,878 (7.2) |

166 (10.9) |

<0.001 |

| Previous ischemic stroke |

184,890 (19.3) |

411 (24.5) |

<0.001 |

150,414 (17.1) |

353 (23.1) |

<0.001 |

| Previous hemorrhagic stroke |

22,823 (2.4) |

69 (4.1) |

<0.001 |

19,937 (2.3) |

67 (4.4) |

<0.001 |

| Atherosclerotic disease |

| Previous MI |

86,067 (9.0) |

268 (16.0) |

<0.001 |

72,206 (8.2) |

232 (15.2) |

<0.001 |

| PAD |

99,696 (10.4) |

260 (15.5) |

<0.001 |

87,147 (9.9) |

217 (14.2) |

<0.001 |

| Vascular disease |

167,773 (17.5) |

468 (27.9) |

<0.001 |

144,284 (16.4) |

404 (26.4) |

<0.001 |

| Heart failure |

258,774 (26.9) |

566 (33.7) |

<0.001 |

221,209 (25.2) |

499 (32.7) |

<0.001 |

| History of malignant neoplasm |

209,089 (21.8) |

604 (36.0) |

<0.001 |

190,240 (21.7) |

540 (35.3) |

<0.001 |

| Hypertension |

688,630 (71.7) |

1,253 (74.7) |

0.007 |

615,282 (70.1) |

1,118 (73.2) |

0.008 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

225,798 (23.5) |

570 (34.0) |

<0.001 |

201,362 (22.9) |

510 (33.4) |

<0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia |

542,536 (56.5) |

1,197 (71.3) |

<0.001 |

485,269 (55.3) |

1,079 (70.6) |

<0.001 |

| COPD |

272,358 (28.4) |

626 (37.3) |

<0.001 |

246,998 (28.1) |

563 (36.8) |

<0.001 |

| CKD |

55,574 (5.8) |

362 (21.6) |

<0.001 |

49,122 (5.6) |

319 (20.9) |

<0.001 |

| History of liver disease |

347,964 (36.2) |

946 (56.4) |

<0.001 |

319,106 (36.3) |

859 (56.2) |

<0.001 |

| Major bleeding |

127,432 (13.3) |

403 (24.0) |

<0.001 |

113,751 (13.0) |

359 (23.5) |

<0.001 |

Values are percentage or mean±standard deviation. Vascular disease: previous MI, PAD or aortic plaque. CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ESRD, endstage renal disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; MI, myocardial infarction; NVAF, non-valvular atrial fibrillation; OAC, oral anticoagulant; PAD, peripheral artery disease; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

OAC-naïve NVAF patients with HIV (n=1,528) were younger and had higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores and more comorbidities than those without HIV (n=878,127) (Table 1).

Primary and Secondary Endpoints in OAC-Naïve NVAF Patients

During the mean follow-up period of 50.6±48.8 months, compared with patients without HIV, OAC-naïve NVAF patients with HIV had higher incidence rates (5.45 vs. 3.73 per 100 person-years, P<0.001) and risk of ischemic stroke/SE (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 1.37, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.21–1.54) (Table 2). The risk for ischemic stroke/SE was consistently increased in patients who were diagnosed with HIV after (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.26–1.76) and before AF diagnosis (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.06–1.49).

Table 2.

Event Rates and Risk for Primary and Second Endpoints in OAC-Naїve NVAF Patients Without and With HIV

| |

Without HIV

(n=878,127) |

HIV

(n=1,528) |

P value |

| Ischemic stroke/systemic embolism |

| No. of events |

130,413 |

274 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

3.73 (3.71–3.75) |

5.45 (4.82–6.13) |

<0.001 |

| Adjusted HR* (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.37 (1.21–1.54) |

<0.001 |

| Ischemic stroke |

| No. of events |

118,473 |

228 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

3.36 (3.34–3.38) |

4.43 (3.87–5.04) |

<0.001 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.28 (1.12–1.46) |

<0.001 |

| Major bleeding |

| No. of events |

99,328 |

262 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

2.88 (2.86–2.90) |

5.29 (4.67–5.97) |

<0.001 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.29 (1.15–1.46) |

<0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding |

| No. of events |

65,383 |

177 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

1.83 (1.82–1.85) |

3.41 (2.92–3.95) |

<0.001 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.23 (1.06–1.43) |

0.005 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage |

| No. of events |

21,379 |

52 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

0.58 (0.58–0.59) |

0.95 (0.71–1.24) |

<0.001 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.27 (0.97–1.67) |

0.084 |

| Acute MI |

| No. of events |

26,663 |

58 |

|

| Incidence/100 PYs (95% CI) |

0.73 (0.73–0.74) |

1.06 (0.81–1.38) |

0.005 |

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) |

Referent |

1.17 (0.90–1.51) |

0.231 |

*HR was adjusted for clinical variables including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, history of hemorrhagic stroke, history of major bleeding, history of ischemic stroke/TIA, dyslipidemia, ESRD, CKD, COPD, liver disease, malignant neoplasm, and vascular disease. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; PYs, person-years. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

The risks of ischemic stroke (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.12–1.46), major bleeding (HR 1.29; 95% CI, 1.15–1.46), and gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 1.23; 95% CI, 1.06–1.43) were also increased in HIV patients compared with non-HIV patients. However, the risk of intracranial bleeding and myocardial infarction was not significantly different between non-HIV and HIV patients (Table 2).

Incidence of Ischemic Stroke/SE and Major Bleeding According to Stroke and Bleeding Risk

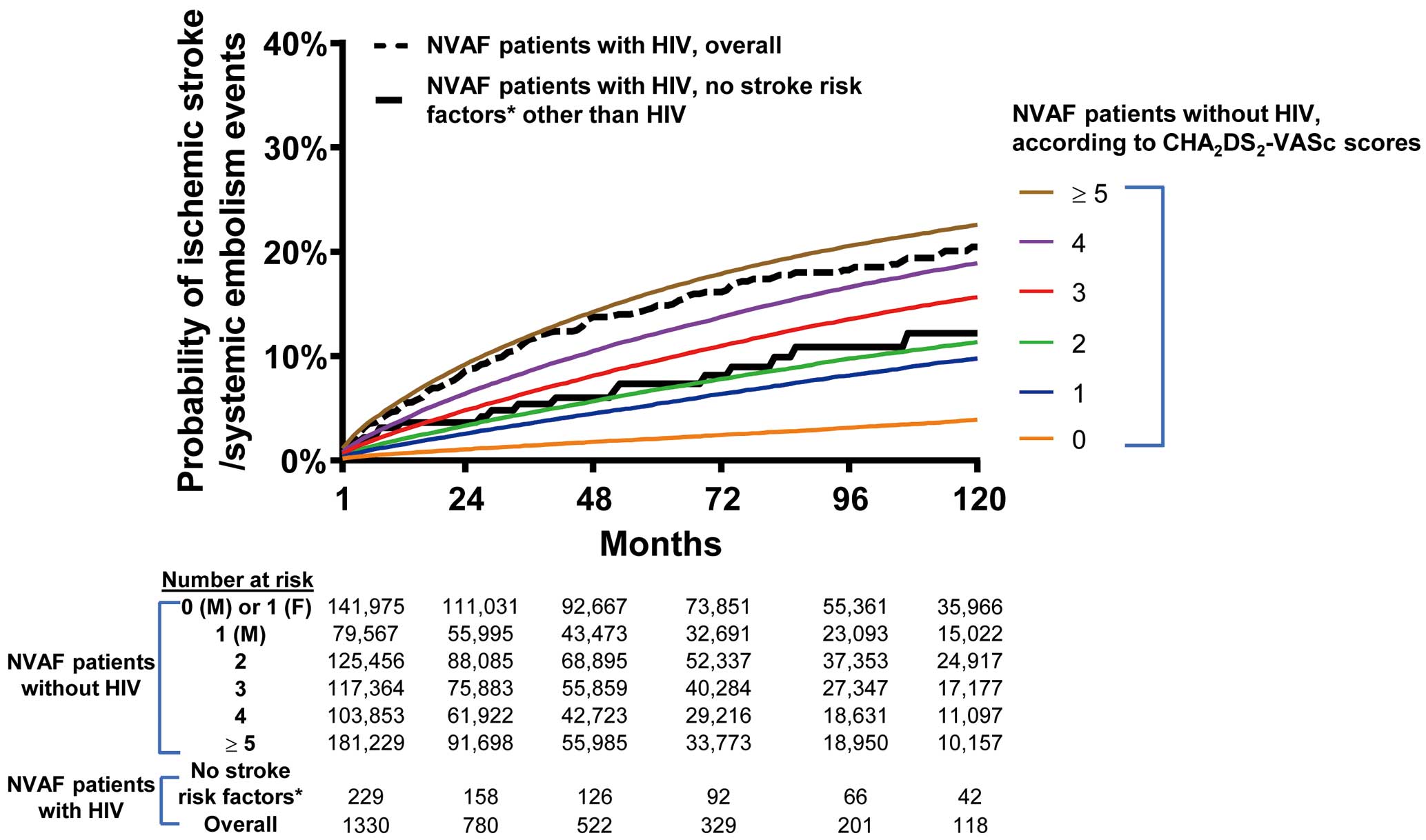

Figure 2

shows the cumulative incidence rates for ischemic stroke/SE to account for the competing risk of death in OAC-naïve NVAF patients with and without HIV. The crude cumulative incidence of ischemic stroke/SE in male HIV patients without any stroke risk factors (thick black line in

Figure 2) was similar to that of non-HIV patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1 (blue line in

Figure 2).

The incidence of ischemic stroke/SE in NVAF patients with HIV at low risk was similar to that of those without HIV at intermediate risk (2.04 vs. 2.18 events per 100 person-years). HIV infection was associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke/SE in all low (HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.30–2.90), intermediate (HR 1.88, 95% CI 1.23–2.85) and high (HR 1.28, 95% CI 1.13–1.46) stroke risk patients (Table 3). The CHA2DS2-VASc score predicted ischemic stroke/SE in HIV and non-HIV patients with c-indexes of 0.603 and 0.635, respectively (both P<0.001).

Table 3.

Incidence Rates and Risk of Ischemic Stroke/Systemic Embolism in Relation to CHA

2DS

2-VASc Scores in OAC-Naїve NVAF Patients With and Without HIV

| Stroke risk |

CHA2DS2-VASc

Score |

HIV |

No. of

patients |

Incidence

(/100 PYs) |

Adjusted HR

(95% CI) |

P value |

| Low |

0 (male) or

1 (female) |

No |

153,595 |

0.93 |

1.95 (1.30–2.90) |

0.001 |

| Yes |

243 |

2.04 |

| Intermediate |

1 (male) |

No |

89,961 |

2.18 |

1.88 (1.23–2.85) |

0.003 |

| Yes |

166 |

3.54 |

| High |

2 |

No |

143,403 |

2.56 |

1.28 (1.13–1.46) |

<0.001 |

| Yes |

212 |

3.60 |

| 3 |

No |

138,891 |

4.07 |

| Yes |

217 |

6.51 |

| 4 |

No |

125,877 |

5.64 |

| Yes |

220 |

5.07 |

| 5 |

No |

98,641 |

7.20 |

| Yes |

184 |

10.34 |

| ≥6 |

No |

127,759 |

10.59 |

| Yes |

286 |

13.14 |

| Overall |

|

No |

878,127 |

3.73 |

1.37 (1.21–1.54) |

<0.001 |

| Yes |

1,528 |

5.45 |

Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

HIV infection was associated with significantly increased risk of major bleeding in both low and high bleeding risk patients (Table 4). The incidence of major bleeding in HIV patients with a HAS-BLED score of 1 was similar to non-HIV patients with HAS-BLED score of 3 (4.23 vs. 3.52 events per 100 person-years). The modified HAS-BLED score predicted major bleeding with c-indexes of 0.547 and 0.565 in HIV and non-HIV, respectively (all P<0.001).

Table 4.

Incidence Rates and Risk of Major Bleeding in Relation to HAS-BLED Scores in OAC-Naїve NVAF Patients With and Without HIV

| Bleeding risk |

HAS-BLED

score |

HIV |

No. of

patients |

Incidence

(/100 PYs) |

Adjusted HR

(95% CI) |

P value |

| Low |

0 |

No |

153,595 |

1.12 |

1.53 (1.27–1.84) |

<0.001 |

| Yes |

243 |

2.13 |

| 1 |

No |

89,961 |

2.11 |

| Yes |

166 |

4.23 |

| 2 |

No |

143,403 |

2.88 |

| Yes |

212 |

6.00 |

| High |

3 |

No |

138,891 |

3.52 |

1.24 (1.06–1.46) |

0.008 |

| Yes |

217 |

4.23 |

| 4 |

No |

125,877 |

4.87 |

| Yes |

220 |

6.13 |

| 5 |

No |

98,641 |

7.49 |

| Yes |

184 |

10.04 |

| 6 |

No |

127,759 |

13.13 |

| Yes |

286 |

15.08 |

| 7 |

No |

449 |

21.12 |

| Yes |

10 |

40.00 |

| Overall |

|

No |

878,127 |

2.88 |

1.29 (1.15–1.46) |

<0.001 |

| Yes |

1,528 |

5.29 |

Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

Among 1,678 NVAF patients with HIV, 150 (8.9%) patients received OAC at the time of AF diagnosis. During the study period, the prescription rate of OAC was 34.0% and 31.6% in HIV-infected patients and non-HIV-infected subjects, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5.

OAC Prescription Rates According to CHA

2DS

2-VASc Scores in NVAF Patients With and Without HIV

| CHA2DS2-VASc score |

NVAF patients without HIV |

NVAF patients with HIV |

No. of

patients |

At the time of

enrollment |

Within follow-up

period |

No. of

patients |

At the time of

enrollment |

Within follow-up

period |

| 0 (male) or 1 (female) |

155,385 |

2,820 (1.8) |

155,385 (18.2) |

244 |

8 (3.3) |

38 (15.6) |

| 1 |

93,837 |

4,400 (46.9) |

29,914 (31.9) |

166 |

1 (0.6) |

29 (17.5) |

| 2+ |

711,216 |

75,076 (10.6) |

268,764 (37.8) |

1,264 |

141 (11.1) |

463 (36.5) |

| Overall |

960,438 |

82,312 (8.6) |

326,883 (34.0) |

1,678 |

150 (8.9) |

530 (31.6) |

Abbreviations as in Tables 1,2.

Compared with OAC non-users, OAC users were older and had more comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, CKD, and vascular disease (all P<0.05). The risk of cardiovascular outcomes, including ischemic stroke/SE, major bleeding, heart failure and myocardial infarction, were similar between OAC users and non-users. However, use of OAC was related to a trend of lower risk of ischemic stroke/SE without statistical significance (adjusted HR 0.90, 95% CI 0.59–1.36) (Supplementary Table 2).

There was no significant difference in the risk of various cardiovascular events between ART users and non-users (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

The principal finding of this study is that NVAF patients with HIV are associated with a higher risk of ischemic stroke/SE than those without HIV. The incidence of ischemic stroke/SE was similar between HIV patients with low stroke risk and non-HIV patients with intermediate stroke risk. Second, despite this, OAC prescription rate was suboptimal in HIV patients, being only 31.6% throughout the study period. Finally, the risk of major bleeding was also higher in HIV patients compared with non-HIV patients. These findings suggested that close follow-up and management of NVAF in patients with HIV are warranted.

Risk of Ischemic Stroke/SE in NVAF Patients With HIV

This study showed that OAC-naïve NVAF patients with HIV had an increased risk of ischemic stroke/SE compared with those without HIV. HIV infection is known to be an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis and stroke,6,19

and similar mechanisms may be involved in the genesis of atherosclerotic CVD and AF. The proportion of ischemic strokes attributed to HIV-infected persons was found to increase in the USA from 1997 to 2006.6,20

The increased stroke rate in HIV infection most probably results from complex interactions among traditional risk factors, direct effects of uncontrolled HIV replication, and the harmful side effects of some antiretroviral medications: inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and macrophage activation.21,22

Despite the high risk of stroke, the OAC prescription rate throughout the present study period was suboptimal, being only 31.6% and 34.0% in AF patients with and without HIV, respectively. The OAC rate in Korea was 36.4–40.3% in AF patients with regular hospital visits as assessed by the NHIS database.2,23

This prescription rate was similar to results from the Taiwan Stroke Registry, where only 28.28% of patients with AF were prescribed OACs.24

Risk of Major Bleeding in NVAF Patients With HIV

In this study, HIV infection was associated with increased risks of major bleeding and GI bleeding in AF patients. The incidence of major bleeding in HIV patients with a HAS-BLED score of 1 was similar to that of non-HIV patients with a HAS-BLED score of 3. The predictive value of the HAS-BLED score in HIV patients was similar to that in non-HIV AF populations.25

Although the incidence of thrombocytopenia has declined in the era of potent ART, the frequency of platelet counts <150,000/mL remains between 10% and 15%.26

The GI tract is one of the most common sites involved in opportunistic processes in patients with AIDS, and up to 90% of HIV-infected patients develop GI manifestations during the course of their disease. Consistently, this study showed that OAC-naïve NVAF patients with HIV had an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding compared with those without HIV. An association of HIV with intracranial bleeding has also been reported.27,28

In this study, patients with HIV showed a trend for higher risk of intracranial bleeding compared with those without HIV, although the trend was not statistically significant.

Study Limitations

Although administrative databases are increasingly used for clinical research, such studies are potentially susceptible to errors arising from coding inaccuracies. To minimize this problem, we applied the definition that we had validated in previous studies that used a Korean NHIS sample cohort.1–4,14

Also, similar to other large administrative databases, the risk of overpowered comparisons (i.e., type 1 error-false positive) may be high. Finally, we were unable to define the type of AF (paroxysmal vs. persistent). Despite these limitations, this study included an evaluation of longitudinal data from the entire Korean adult population. Therefore, our findings reflect the ischemic stroke risk in OAC-naïve AF patients with HIV on a nationwide scale.

Conclusions

The risks of ischemic stroke/SE and major bleeding were significantly higher in HIV-infected vs. non-HIV-infected AF patients. Despite this, the actual use of OACs among AF patients with HIV was suboptimal.

Acknowledgments

This study used the National Health Information Database (NHIS-2018-4-018) provided by the National Health Insurance Service of Korea.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by a research grant from the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (NRF-2017R1A2B3003303) and grants from the Korean Healthcare Technology R&D project funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare (HC16C0058, HC15C1200).

Disclosures

G.Y.H.L.: Consultant for Bayer/Janssen, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Verseon and Daiichi-Sankyo. Speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo. No fees directly received personally. B.J.: Speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, and Daiichi-Sankyo, and recipient of research funds from Medtronic and Abbott. No fees directly received personally. None of the other authors have any disclosures.

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0527

References

- 1.

Kim D, Yang PS, Jang E, Yu HT, Kim TH, Uhm JS, et al. 10-year nationwide trends of the incidence, prevalence, and adverse outcomes of non-valvular atrial fibrillation nationwide health insurance data covering the entire Korean population. Am Heart J 2018; 202: 20–26.

- 2.

Kim D, Yang PS, Jang E, Yu HT, Kim TH, Uhm JS, et al. Increasing trends in hospital care burden of atrial fibrillation in Korea, 2006 through 2015. Heart 2018; 104: 2010–2017.

- 3.

Kim TH, Yang PS, Kim D, Yu HT, Uhm JS, Kim JY, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc score for identifying truly low-risk atrial fibrillation for stroke: A Korean nationwide cohort study. Stroke 2017; 48: 2984–2990.

- 4.

Kim TH, Yang PS, Uhm JS, Kim JY, Pak HN, Lee MH, et al. CHA2DS2-VASc Score (Congestive Heart Failure, Hypertension, Age >/=75 [Doubled], Diabetes Mellitus, Prior Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack [Doubled], Vascular Disease, Age 65–74, Female) for stroke in Asian patients with atrial fibrillation: A Korean nationwide sample cohort study. Stroke 2017; 48: 1524–1530.

- 5.

d’Arminio A, Sabin CA, Phillips AN, Reiss P, Weber R, Kirk O, et al. Cardio- and cerebrovascular events in HIV-infected persons. AIDS 2004; 18: 1811–1817.

- 6.

Chow FC, Regan S, Feske S, Meigs JB, Grinspoon SK, Triant VA. Comparison of ischemic stroke incidence in HIV-infected and non-HIV-infected patients in a US health care system. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012; 60: 351–358.

- 7.

Chow FC, He W, Bacchetti P, Regan S, Feske SK, Meigs JB, et al. Elevated rates of intracerebral hemorrhage in individuals from a US clinical care HIV cohort. Neurology 2014; 83: 1705–1711.

- 8.

Hopkins RS, Jajosky RA, Hall PA, Adams DA, Connor FJ, Sharp P, et al. Summary of notifiable diseases: United States, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2005; 52: 1–85.

- 9.

Feinstein MJ, Hsue PY, Benjamin LA, Bloomfield GS, Currier JS, Freiberg MS, et al. Characteristics, prevention, and management of cardiovascular disease in people living with HIV: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019; 140: e98–e124.

- 10.

Triant VA, Lee H, Hadigan C, Grinspoon SK. Increased acute myocardial infarction rates and cardiovascular risk factors among patients with human immunodeficiency virus disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 92: 2506–2512.

- 11.

Freiberg MS, Chang CC, Kuller LH, Skanderson M, Lowy E, Kraemer KL, et al. HIV infection and the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 614–622.

- 12.

Hsu JC, Li Y, Marcus GM, Hsue PY, Scherzer R, Grunfeld C, et al. Atrial fibrillation and atrial flutter in human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons: Incidence, risk factors, and association with markers of HIV disease severity. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: 2288–2295.

- 13.

Sanders JM, Steverson AB, Pawlowski AE, Schneider D, Achenbach CJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Atrial arrhythmia prevalence and characteristics for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons and matched uninfected controls. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0194754.

- 14.

Kim D, Yang PS, Kim TH, Jang E, Shin H, Kim HY, et al. Ideal blood pressure in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018; 72: 1233–1245.

- 15.

Jung H, Yang PS, Sung JH, Jang E, Yu HT, Kim TH, et al. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in patients with atrial fibrillation: Prevalence and associated stroke risks in a nationwide cohort study. J Thromb Haemost 2019; 119: 285–293.

- 16.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Frequency of HIV testing and time from infection to diagnosis improve. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p1128-frequency-hiv-testing.html/ (accessed November 28, 2017).

- 17.

World Health Organization. WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children. WHO, Geneva, 2006. https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/HIVstaging150307.pdf?ua=1 (accessed May 17, 2019).

- 18.

Lee SS, Ae Kong K, Kim D, Lim YM, Yang PS, Yi JE, et al. Clinical implication of an impaired fasting glucose and prehypertension related to new onset atrial fibrillation in a healthy Asian population without underlying disease: A nationwide cohort study in Korea. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2599–2607.

- 19.

Grunfeld C, Delaney JA, Wanke C, Currier JS, Scherzer R, Biggs ML, et al. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: Carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS 2009; 23: 1841–1849.

- 20.

Ovbiagele B, Nath A. Increasing incidence of ischemic stroke in patients with HIV infection. Neurology 2011; 76: 444–450.

- 21.

Wang X, Chai H, Yao Q, Chen C. Molecular mechanisms of HIV protease inhibitor-induced endothelial dysfunction. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 44: 493–499.

- 22.

Worm SW, Sabin C, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with HIV infection exposed to specific individual antiretroviral drugs from the 3 major drug classes: The data collection on adverse events of anti-HIV drugs (D: A: D) study. J Infect Dis 2010; 201: 318–330.

- 23.

Yang PS, Ryu S, Kim D, Jang E, Yu HT, Kim TH, et al. Variations of prevalence and incidence of atrial fibrillation and oral anticoagulation rate according to different analysis approaches. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 6856.

- 24.

Hsieh FI, Lien LM, Chen ST, Bai CH, Sun MC, Tseng HP, et al. Get With the Guidelines-Stroke performance indicators: Surveillance of stroke care in the Taiwan Stroke Registry: Get With the Guidelines-Stroke in Taiwan. Circulation 2010; 122: 1116–1123.

- 25.

Borre ED, Goode A, Raitz G, Shah B, Lowenstern A, Chatterjee R, et al. Predicting thromboembolic and bleeding event risk in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation: A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2018; 118: 2171–2187.

- 26.

Morris L, Distenfeld A, Amorosi E, Karpatkin S. Autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura in homosexual men. Ann Intern Med 1982; 96: 714–717.

- 27.

Durand M, Sheehy O, Baril JG, LeLorier J, Tremblay CL. Risk of spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage in HIV-infected individuals: A population-based cohort study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2013; 22: e34–e41.

- 28.

Behrouz R, Topel CH, Seifi A, Birnbaum LA, Brey RL, Misra V, et al. Risk of intracerebral hemorrhage in HIV/AIDS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurovirol 2016; 22: 634–640.