2019 年 83 巻 12 号 p. 2434-2442

2019 年 83 巻 12 号 p. 2434-2442

Background: Guideline-adherent antithrombotic treatment (ATT) reduces the risk of stroke and death in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). However, the effect of ATT adherence among different ethnicities remains uncertain. We compared the prognosis of AF patients in Japan and the UK according to guideline adherence status.

Methods and Results: We compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes of AF patients from the Fushimi AF registry (Japan; n=4,239) and the Darlington AF registry (UK; n=2,259). ATT adherence was assessed against the Japanese Circulation Society Guidelines and UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines. The rates of guideline-adherent ATT were 58.6% and 50.8% in the Fushimi and Darlington registries, respectively. There was no significant difference in 1-year stroke rates between Fushimi and Darlington (2.6% vs. 3.0%, P=0.342). On multivariate logistic regression analysis, non-guideline adherent-ATT was significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke (odds ratio [OR]: 1.69, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21–2.34, P=0.002 for undertreatment, OR: 2.13, 95% CI: 1.19–3.80, P=0.010 for overtreatment). No significant interaction for ATT and the 2 populations was found in the incidence of stroke, all-cause death, and the composite outcome.

Conclusions: Approximately half of the AF patients received optimal ATT according to guideline recommendations, which was associated with a lower risk of stroke. Furthermore, there was no interaction for the 2 populations and the influence of ATT adherence.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is associated with an increased risk of stroke and death.1 In particular, AF-related stroke is more likely to be fatal or severely disabling.2 Risk factors for stroke in patients with AF have been widely described, and current guidelines recommend that AF patients with moderate to high risk of stroke should be anticoagulated.3,4 Indeed, oral anticoagulation (OAC) is well established as effective stroke prevention and also reduces the risk of stroke and death.5

Editorial p 2413

Despite advances in the management of AF patients, a recent global registry demonstrated that 20% of AF patients at risk for stroke were not prescribed OAC or were treated with antiplatelet therapy alone, while approximately 50% of patients with no risk factors were unnecessarily prescribed OAC.6 Optimal antithrombotic treatment (ATT) for stroke prevention in AF is based on thromboembolic risk assessment, but OAC prescription sometimes depends on physician discretion and the definition of guideline adherence may also vary according to currently applied stroke risk stratification schemes and guidelines, which vary slightly by country or region.7

Guideline recommendations advocated in each country or region have been established on the basis of data from large clinical trials and international AF registries, as well as data from each national AF registry. Although the CHA2DS2-VASc score is most widely used for stroke risk stratification, the CHADS2 and CHADS-65 scores are still recommended for decision making of OAC prescription.8,9 There are clear regional differences in the incidence of AF and AF-related stroke, especially between Asian and non-Asian populations.10 Indeed, the CHADS2 score is currently recommended for risk stratification in the Japanese AF guideline, whereas the CHA2DS2-VASc score is recommended in UK AF guideline. Previous studies have reported that guideline-adherent ATT reduces the risk of stroke and death,11,12 but the effect of guideline-adherent ATT applied according to different risk stratification schemes and different ethnicities on clinical outcomes remains uncertain.

Our objectives of the present study were first to compare the clinical characteristics, guideline adherence in ATT and clinical outcomes between 2 individual patient-level cohorts from Japanese and UK AF registries, and second to assess the effect of guideline-adherent ATT on clinical outcomes in these populations according to each risk stratification.

The designs of the Fushimi AF registry and the Darlington AF registry have been previously described.13,14 In brief, the Fushimi AF registry (UMIN Clinical Trials Registry: UMIN000005834) is a prospective, observational, community-based survey of patients with AF in Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, Japan. Fushimi-ku is an urban administrative district in the southern area of the city of Kyoto, with a total population of 284,000 (Japanese were >99%) in 2011, and 80 institutions (all members of Fushimi-Ishikai (Fushimi Medical Association)) participated in this registry. Follow-up data were collected annually through review of inpatient and outpatient medical records, and contact with patients, relatives and/or referring physicians by mail or telephone. The study protocol was approved by the ethical committees of the National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center and Ijinkai Takeda General Hospital.

The study population of the Darlington AF registry was derived from all 105,000 patients who were registered at 11 general practices serving the town of Darlington, UK, which is a market town with a resident population of 106,000 in 2011. The Guidance on Risk Assessment and Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (GRASP-AF) tool was used to collect data. All general practices were equipped with this electronic record interrogation software, which was designed to support primary care physicians in population-based screening for stroke risk factors and to facilitate decision making for OAC prescription.14,15 According to the last census data in the Darlington cohort, >96% of population were Caucasian.

In the Fushimi AF registry, the participating institutions attempted to recruit all consecutive patients who were diagnosed with AF documented on 12-lead ECG or Holter ECG monitoring under regular outpatient care or under hospital admission. The enrollment of patients started in March 2011 and a total of 4,239 patients were enrolled by July 2017. In the Darlington AF registry, the participating general practices enrolled all patients with evidence of AF or atrial flutter, whose vital status in March 2013 was known, and a total of 2,259 patients with AF were enrolled.

Differences in the method of data collection between registries were seen. The Darlington AF registry was a completed study that dealt with a closed cohort and had 100% follow-up data. In contrast, the Fushimi AF registry was an ongoing cohort at the time of the present analyses. Therefore, to ensure an equivalent period for both registries, we analyzed the follow-up data at 12 months.

Clinical OutcomesClinical outcomes assessed in the present study were stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic), and all-cause death. Stroke was defined as the sudden onset of a focal neurologic deficit in a location consistent with the territory of a major cerebral artery, and the diagnosis of stroke was confirmed by the clinical picture of cerebrovascular accident, physical examination, and cerebral imaging (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging).

Guideline Adherence in ATTGuideline adherence in ATT was assessed at the time of enrollment in the registry, and referred to either the 2013 Japanese Circulation Society (JCS) Guidelines for the Fushimi AF registry or the 2014 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the Darlington AF registry.8,16 We categorized ATT use into 3 categories (Table 1): guideline adherent, overtreatment (OAC overuse) and undertreatment (OAC underuse). The JCS guideline recommended the CHADS2 score for stroke risk stratification scheme, and the NICE guideline recommended the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Furthermore, the NICE guideline referred to combination therapy of OAC and antiplatelet drugs for AF patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and no ATT for patients with contraindications to OAC/antiplatelet drugs or therapy decline.

| Guideline adherence | Undertreatment | Overtreatment |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 JCS guideline* | ||

| - OAC in moderate- or high-risk patients - No OAC in low-risk patients |

- No OAC in moderate- or high-risk patients | - OAC in low-risk patients |

| 2014 NICE guideline** | ||

| - OAC in moderate- or high-risk patients - OAC+APT in patients with recent AMI - No OAC in low-risk patients or in patients with contraindications to OAC or therapy decline |

- No OAC in moderate- or high-risk patients - No OAC+APT in patients with recent AMI |

- OAC in low-risk patients or in patients with contraindications to OAC - OAC+APT in patients without recent AMI - APT in patients with contraindications to OAC and APT |

*Moderate or high risk as CHADS2 score ≥1, low risk as CHADS2 score 0. **Moderate or high risk as CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 in males and ≥2 in females, low risk as CHA2DS2-VASc score 0 in males and 1 in females. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; APT, antiplatelet therapy; ATT, antithrombotic treatment; JCS, Japanese Circulation Society; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; OAC, oral anticoagulant.

In the Fushimi AF registry, guideline adherence was defined as OAC in patients with moderate or high risk of stroke (CHADS2 score ≥1), or no OAC in patients with low risk of stroke (CHADS2 score 0). Undertreatment was defined as no OAC or antiplatelet therapy alone in patients with moderate or high risk. Overtreatment was defined as OAC in patients with low risk. In the JCS guideline, ATT for patients with low risk and ≥1 of age 65–74 years, vascular disease, or cardiomyopathy, is supposed to be neither guideline adherence nor non-adherence as these risk factors have not been sufficiently validated in the Japanese AF population. Thus, we excluded a total of 254 patients with low risk who had ≥1 of those factors from the present study irrespective of OAC prescription.

In the Darlington AF registry, guideline adherence was defined as OAC in patients with moderate or high risk of stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 in males, ≥2 in females); combination therapy (OAC+antiplatelet drugs) in patients with acute vascular disease (i.e., recent AMI); and no OAC in patients with low risk of stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 in males, 1 in females) or in patients with reported contraindications to OAC or therapy decline. Undertreatment was defined as: no OAC or antiplatelet therapy alone in patients with moderate or high risk; no OAC in patients without reported contraindications to OAC or therapy decline; and no combination therapy (OAC+antiplatelet drugs) in patients with recent AMI. Overtreatment was defined as OAC in patients with low risk; combination therapy (OAC+antiplatelet drugs) in patients with no evidence of acute vascular disease; OAC in patients with reported contraindications to anticoagulation therapy; and antiplatelet therapy in patients with reported contraindications to both OAC and antiplatelet therapy.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. Censoring was done for the first event recorded. We compared categorical variables using the chi-square test and continuous variables using an independent samples t-test for normally distributed data or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal distribution. Baseline characteristics, stroke risk profiles, and ATT, as well as outcome events, were tabulated in relation to the 3 categories (undertreatment, guideline adherence, and overtreatment).

To determine independent risk factors for stroke and all-cause death, we performed multivariate logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vascular disease and ATT (undertreatment, guideline adherence [as reference], and overtreatment) at baseline as co-variates. The analyses were performed using JMP version 13.2.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set as a two-sided P-value <0.05.

Overall, the AF patients in the Fushimi registry were significantly younger, with fewer females, more likely to have hypertension and heart failure, and less likely to have vascular disease, compared with those in the Darlington registry (Table 2). Mean CHADS2 score was significantly higher in the Fushimi registry patients, but the mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was similar in the 2 registries. Overall, OAC were prescribed more often in the Fushimi cohort than in the Darlington cohort (55.7% vs. 47.8%; P<0.001); prescription of vitamin K antagonists (VKAs, predominantly warfarin) was significantly higher in the Darlington registry (46.4% vs. 43.1%; P=0.012), whereas prescription of non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOAC) was significantly higher in the Fushimi registry (12.6% vs. 1.4%; P<0.001). On the other hand, use of antiplatelet drugs was significantly higher in the Darlington registry (40.8% vs. 28.1%; P<0.001), whereas combination use of OAC and antiplatelet drugs was significantly more frequent in the Fushimi registry (13.0% vs. 4.8%; P<0.001).

| Fushimi AF registry (Japan) (n=3,985) |

Darlington AF registry (UK) (n=2,259) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics (n [%]) | |||

| Mean age (SD), years | 73.9 (11.1) | 75.6 (12.2) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1,621 (40.7) | 1,041 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| Medical history (n [%]) | |||

| Hypertension | 2,655 (66.6) | 1,404 (62.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 996 (25.0) | 490 (21.7) | 0.003 |

| Heart failure | 1,151 (28.9) | 514 (22.8) | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke | 829 (20.8) | 428 (19.0) | 0.079 |

| Vascular disease | 395 (9.9) | 389 (17.2) | <0.001 |

| Thromboembolic risk | |||

| Mean CHADS2 score (SD) | 2.16 (1.27) | 2.04 (1.38) | <0.001 |

| Mean CHA2DS2-VASc score (SD) | 3.48 (1.65) | 3.51 (1.80) | 0.539 |

| Antithrombotic medication (n [%]) | |||

| OAC | 2,221 (55.7) | 1,080 (47.8) | <0.001 |

| VKA | 1,718 (43.1) | 1,048 (46.4) | 0.012 |

| NOAC | 503 (12.6) | 32 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet | 1,121 (28.1) | 921 (40.8) | <0.001 |

| OACs+antiplatelet | 517 (13.0) | 109 (4.8) | <0.001 |

| Antithrombotic treatment (n [%]) | |||

| Guideline adherence | 2,334 (58.6) | 1,147 (50.8) | <0.001 |

| Undertreatment | 1,595 (40.0) | 816 (36.1) | 0.002 |

| Overtreatment | 56 (1.4) | 296 (13.1) | <0.001 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; NOAC, non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants; OAC, oral anticoagulant; VKA, vitamin K antagonist.

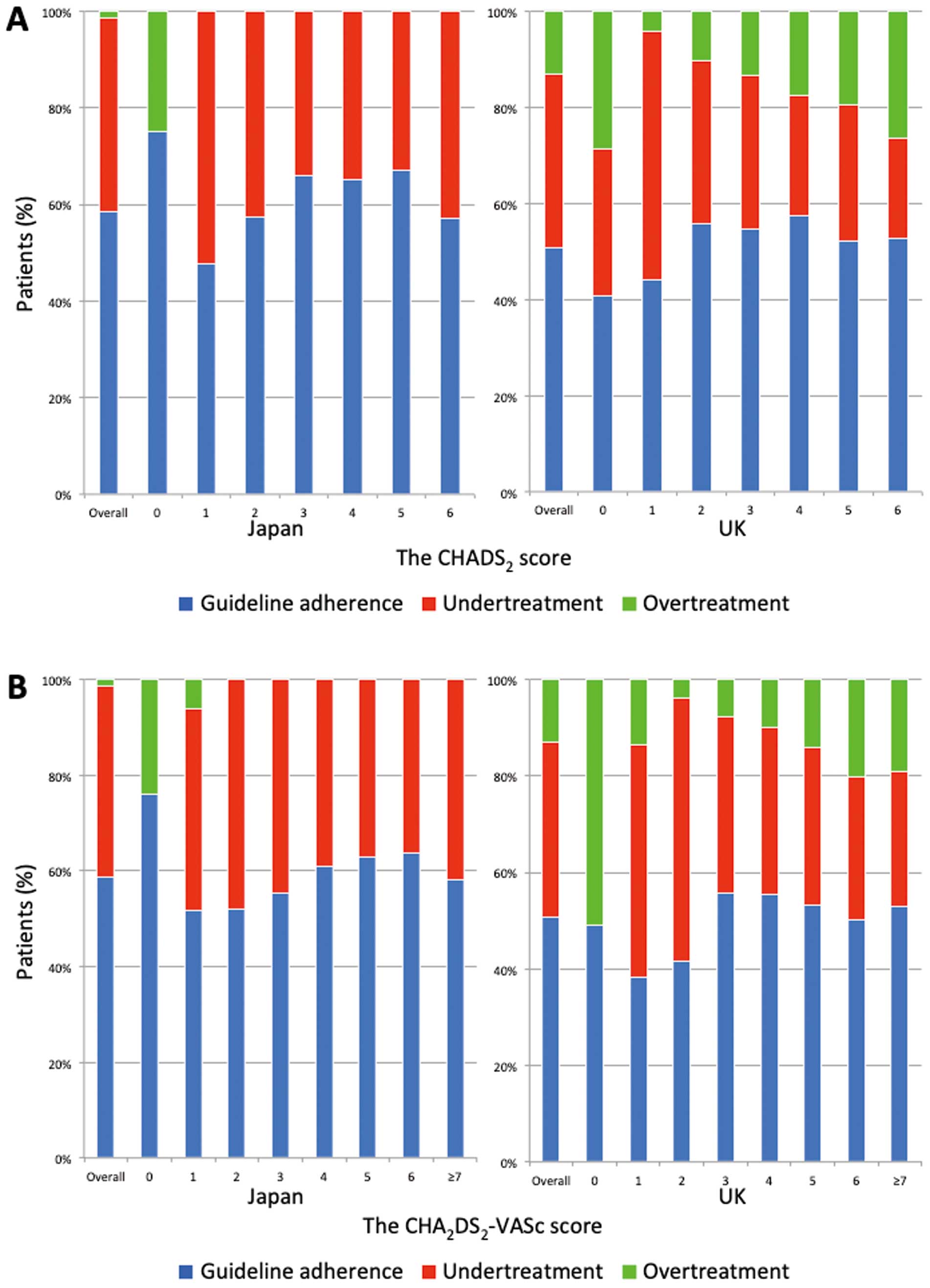

Approximately half of patients were treated with guideline-adherent ATT (58.6% in the Fushimi registry and 50.8% in the Darlington registry, P<0.001), with undertreatment of 40.0% and 36.1% (P=0.002), and overtreatment of 1.4% and 13.1% (P<0.001), respectively. In patients with moderate or high risk of stroke (i.e., CHADS2 score ≥1 in the Fushimi registry and CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥1 in males ≥2 in females in the Darlington registry), OACs were prescribed more often in the Fushimi registry compared with the Darlington registry (P<0.001). In patients with low risk (i.e., CHADS2 score 0 in the Fushimi registry and CHA2DS2-VASc score 0 in males, 1 in females in the Darlington registry), OAC prescription was similar in both registries (P=0.626) (Supplementary Figure). The proportions of AF patients receiving each ATT in relation to thromboembolic risk scores are shown in Figure 1A (CHADS2) and Figure 1B (CHA2DS2-VASc). The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients in the Fushimi and Darlington registries according to each guideline-adherent ATT are shown in the Supplementary Table.

Proportion of AF patients receiving each ATT according to guideline recommendation based on the score in each stroke risk scheme: (A) CHADS2 score, (B) CHA2DS2-VASc score. AF, atrial fibrillation; ATT; antithrombotic treatment.

During the 1-year follow-up, the observed rates of stroke and all-cause death were 2.7% (n=169) and 8.5% (n=528) in the 2 registries, respectively (Table 3). There was no significant difference in the stroke rate between registries (102 [2.6%] vs. 67 [3.0%], P=0.342), even in the guideline-adherent subgroups of each registry. On the other hand, all-cause death occurred more often in the Fushimi registry compared with the Darlington registry (314 [7.9%] vs. 214 [9.5%], P=0.03), but was not observed in each guideline-adherent subgroup.

| Stroke | OR (95% CI) |

P value |

All-cause death | OR (95% CI) |

P value |

Stroke+ all-cause death |

OR (95% CI) |

P value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fushimi AF registry (n=3,985) |

Darlington AF registry (n=2,259) |

Fushimi AF registry (n=3,985) |

Darlington AF registry (n=2,259) |

Fushimi AF registry (n=3,985) |

Darlington AF registry (n=2,259) |

|||||||

| All patients (n [%]) |

102 (2.6) |

67 (3.0) |

0.86 (0.63– 1.17) |

0.342 | 314 (7.9) |

214 (9.5) |

0.82 (0.68– 0.98) |

0.030 | 395 (9.9) |

256 (11.3) |

0.86 (0.73– 1.02) |

0.078 |

| Antithrombotic treatment (n [%]) | ||||||||||||

| Guideline adherence |

55 (2.4) |

20 (1.7) |

1.36 (0.81– 2.28) |

0.242 | 128 (5.5) |

81 (7.1) |

0.76 (0.57– 1.02) |

0.066 | 173 (7.4) |

197 (8.5) |

0.87 (0.67– 1.12) |

0.279 |

| Undertreatment | 47 (3.0) |

32 (3.9) |

0.74 (0.47– 1.18) |

0.203 | 185 (11.6) |

115 (14.1) |

0.80 (0.62– 1.03) |

0.079 | 221 (13.9) |

126 (15.4) |

0.88 (0.69– 1.12) |

0.294 |

| Overtreatment | 0 (0.0) |

15 (5.1) |

0 | 0.085 | 1 (1.8) |

18 (6.1) |

0.28 (0.04– 2.15) |

0.192 | 1 (1.8) |

323 (11.2) |

0.14 (0.02– 1.08) |

0.030 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

On multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 4), non-guideline-adherent ATT was significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke (odds ratio [OR]: 1.69, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21–2.34, P=0.002 for undertreatment; OR: 3.13, 95% CI: 1.19–3.80, P=0.010 for overtreatment). Undertreatment with ATT was also associated with a higher risk of all-cause death (OR: 2.39, 95% CI: 1.97–2.90, P<0.001), but overtreatment with ATT was not associated (OR: 1.00, 95% CI: 0.61–1.65, P=0.997).

| Stroke | All-cause morality | Stroke+all-cause morality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age <65 years | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Age 65–74 years | 1.46 (0.76–2.81) | 0.262 | 2.14 (1.31–3.51) | 0.003 | 1.91 (1.26–2.87) | 0.002 |

| Age ≥75 years | 2.32 (1.28–4.21) | 0.006 | 5.13 (3.27–8.07) | <0.001 | 4.32 (2.98–6.27) | <0.001 |

| Female sex | 1.14 (0.83–1.57) | 0.428 | 1.20 (0.99–1.45) | 0.058 | 1.11 (0.93–1.32) | 0.255 |

| Hypertension | 1.09 (0.78–1.52) | 0.626 | 0.91 (0.74–1.10) | 0.326 | 0.93 (0.78–1.11) | 0.431 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.46 (1.04–2.05) | 0.027 | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 0.647 | 1.11 (0.91–1.35) | 0.290 |

| Heart failure | 1.10 (0.78–1.55) | 0.594 | 2.23 (1.84–2.70) | <0.001 | 1.95 (1.63–2.33) | <0.001 |

| Previous stroke | 2.93 (2.12–4.03) | <0.001 | 1.69 (1.37–2.09) | <0.001 | 2.04 (1.69–2.46) | <0.001 |

| Vascular disease | 1.24 (0.82–1.87) | 0.309 | 1.97 (1.57–2.47) | <0.001 | 1.77 (1.43–2.19) | <0.001 |

| Antithrombotic treatment | ||||||

| Guideline adherence | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||

| Undertreatment* | 1.69 (1.21–2.34) | 0.002 | 2.39 (1.97–2.90) | <0.001 | 2.19 (1.83–2.61) | <0.001 |

| Overtreatment* | 2.13 (1.19–3.80) | 0.010 | 1.00 (0.61–1.65) | 0.997 | 1.44 (0.97–2.14) | 0.068 |

Adjusted for components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score, antithrombotic treatment, and ethnicity. *Guideline adherence as a reference. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

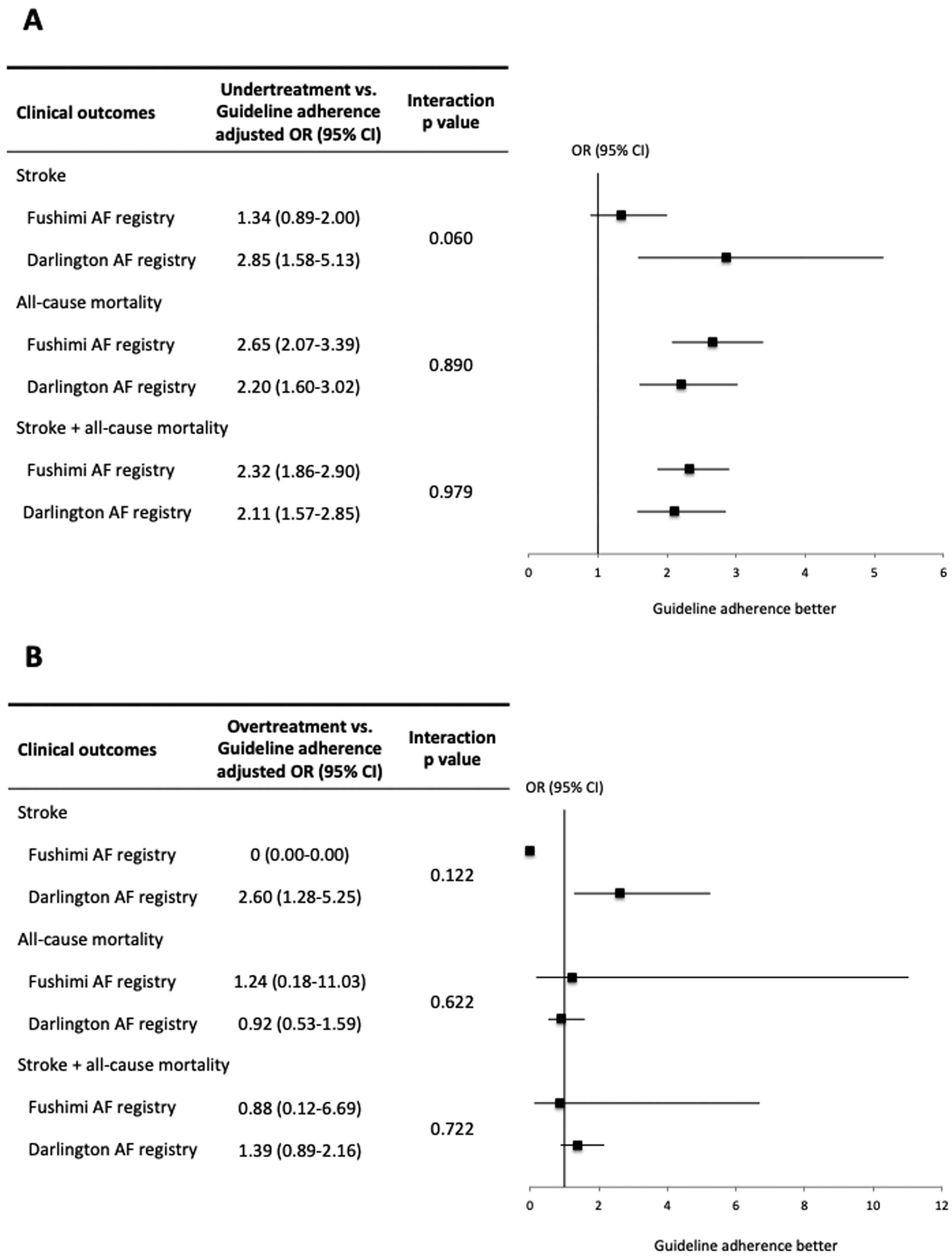

The adjusted ORs of clinical outcomes for undertreatment with ATT compared with guideline-adherent ATT are shown in Figure 2A. The risks of stroke, all-cause death, and the composite outcome were comparable in the Fushimi and Darlington subgroups, and there were no significant interactions for ATT and the 2 populations in all of the outcomes (P=0.060, P=0.890, P=0.979 for the interaction, respectively). Similarly, comparing overtreatment vs. guideline-adherent ATT, no significant interactions for ATT and the 2 populations were found for the outcomes of stroke or all-cause death or the composite outcome (P=0.122, P=0.622, P=0.722 for the interaction, respectively) (Figure 2B).

Adjusted odds ratio (OR) for stroke, all-cause death and composite outcome comparing (A) guideline adherence vs. undertreatment and (B) guideline adherence vs. overtreatment, according to each registry subgroup. Forest plots show OR with error bars indicating 95% CI. AF, atrial fibrillation; CI, confidence interval.

The main finding of the present study was that only half of the AF patients received optimal ATT for stroke prevention in line with each country’s current guideline recommendations. Second, guideline-adherent ATT was significantly associated with a lower risk of stroke and all-cause death, and there was no significant interaction for the 2 populations and the influence of ATT adherence according to each guideline recommendation on clinical outcomes. This is a unique individual patient-level comparison from Japan and the UK of clinical characteristics and outcomes, in relation to guideline-adherent ATT management. To the best of our knowledge, no previous “real world” study has investigated and compared guideline adherence in ATT between different ethnicities, using individual patient-level data.

Current Use of ATTIn recent years, the reported prevalence of AF has been increasing because of ageing populations, increasing risk factors, and advances in diagnostic methods.17 Because of the epidemic of AF, thromboprophylaxis based on risk stratification (e.g., CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores) is recommended in current guidelines. However, in practice, many AF patients are managed with suboptimal ATT.6

In the present community-based studies, OAC therapy was underused (<60%) and antiplatelet therapy alone was prescribed in 30–40% of patients in both the Japanese and UK AF populations, which is in accordance with other AF cohorts previously published in both Japan and UK.15,18 OACs were prescribed slightly more frequently in the Fushimi registry, whereas antiplatelet drugs were more often prescribed in the Darlington registry.

In contemporary trials and registries, approximately 15% of AF patients have a history of vascular disease such as MI.19–21 There were fewer patients with vascular disease in the Fushimi registry, but the concomitant use of OAC and antiplatelet drugs was conversely lower in the Darlington registry. Use of combination therapy has been associated with an increased risk of major bleeding, but with no reduction in the risk of stroke.21,22 Thus, the current NICE and ESC guidelines recommend OAC monotherapy in AF patients with stable coronary artery disease (i.e., without an acute coronary syndrome and/or coronary intervention in the previous 12 months).3,16 However, the optimal combination therapy and duration of treatment in such patients are still debated.

Guideline Adherence for ATT and EthnicitySeveral stroke risk stratification schemes have been developed and validated in various populations. The CHA2DS2-VASc score is commonly advocated in most guidelines, but other scores (e.g., CHADS2 and CHADS-65) are still used for stroke risk stratification in some countries.4 Irrespective of any guideline recommendations, use of guideline-adherent ATT significantly reduces the incidence of stroke and improves survival; non-adherent ATT is associated with worse outcomes.11,12 In the present study, although the definitions of ATT were separately assessed by each national guideline, approximately half of the AF patients in both registries were treated with non-guideline-adherent ATT, which was significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke even after adjustment for potential confounders (i.e., the components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score). Furthermore, undertreatment with ATT was also an independent factor associated with increased risks of all-cause death and the composite outcome, suggesting that optimal anticoagulation therapy following the evidence in current guidelines may reduce stroke-related sequelae such as death, disability and cognitive impairment, and thus, healthcare costs. On the other hand, overtreatment with ATT was not associated with increased risks of all-cause death and the composite outcome. Previous studies have also reported overtreatment as not being associated with major bleeding or cardiovascular death.12 The possible explanation for this result is that aggressive or excessive ATT may lead to a slightly low level of anticoagulation control or use of NOAC with reduced doses for fear of bleeding complications. Furthermore, as shown in the Supplementary Table, the mean CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores in patients with overtreatment were relatively similar or rather lower compared with those on guideline-adherent ATT. Indeed, approximately 30% of patients with overtreatment were low risk (CHA2DS2-VASc score of 0 in males and ≤1 in women), which may affect the non-superior outcomes of guideline-adherent ATT compared with overtreatment.

Clinical characteristics and ATT adherence were clearly different in the 2 populations, but the present study showed that there was no interaction for the 2 populations and the influence of ATT adherence according to each guideline recommendation on clinical outcomes. There are clear regional differences in AF epidemiology.10 Indeed, the prevalence of AF in Western countries is higher than in Asian countries, and the risk factors for AF, such as hypertension, heart failure, and vascular disease, also differ across different ethnic groups. On the other hand, the rates of ischemic stroke and major bleeding in the Asian population have been reported as higher than in the non-Asian population.23–25 The exact mechanisms underlying the ethnic and regional variations in AF remain uncertain, but may partially be attributable to differences in genetics and environmental factors.26 Therefore, current guidelines are established according to the evidence for each region or country, suggesting that ATT adherence according to the particular regional/national guideline recommendations may be crucial for the management of individual patients in each region or country.

Study LimitationsFirst, the present study was a combined dataset from different cohorts of AF patients in Japan and the UK. Some differences between the 2 registries in the study period and the definitions of guideline-adherent ATT were evident. Moreover, comparative data between registries were not available for stroke risk assessment according to each guideline recommendation. Indeed, there was a relatively small number of patients with overtreatment in the Fushimi registry because contraindications to OAC, therapy refusal and OAC monotherapy in AF patients without recent AMI are currently not taken into account in the JCS guideline. In addition, for the same reason, we could not assess whether patients were differently treated according to the other guideline recommendation. These factors may potentially be linked to the incidence of stroke or worse prognosis. Second, we assessed neither the quality of anticoagulation control in VKA-treated patients (e.g., time in therapeutic range [TTR]) nor the optimal dose of NOACs in accordance with recommendations. In prior studies, there was a significant association between TTR and the risk of thromboembolic events.27 Similarly, inappropriate NOAC dosing has been reported to be associated with worse safety with no benefit in effectiveness.28 Third, there was a lack of data pertaining to bleeding risk assessment and outcomes because the Darlington registry did not collect data on bleeding risk profiles and events. Decision making of ATT recommended in the current guidelines is based on positive net clinical benefit when balancing the risk of stroke against the risk of bleeding complications.29 However, patients may be more likely to endure major bleeding events in order to prevent thromboembolic events,30 leading to some cases of ATT overtreatment based on our definition. Fourth, results from the present study were based on antithrombotic medication at the time of enrollment into the registries. As expected, discontinuation of OAC during follow-up would affect clinical outcomes, and we had limited information on this.31

Approximately half of the AF patients were prescribed optimal ATT in accordance with each country’s current guideline recommendations. Guideline-adherent ATT was significantly associated with a lower risk of stroke and all-cause death. Furthermore, there was no significant interaction for the 2 populations and the influence of ATT adherence according to each guideline recommendation on clinical outcomes.

None directly related to this manuscript.

The Fushimi AF registry is supported by research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novartis Pharma, MSD, Sanofi-Aventis and Takeda Pharmaceutical. This research was partially supported by the Practical Research Project for Life-Style related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED (18ek0210082 h0002, 18ek0210056 h0003).

Dr. Lane has received investigator-initiated educational grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim; and has been a speaker and consultant for Boehringer Ingelheim, and Bristol-Myers Squibb/Pfizer. Dr. Wolff has been a clinical advisor to and has received educational grants and investigator payments from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi-Aventis, and Daiichi-Sankyo; and has served as speaker for Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, and Pfizer. Dr. Akao has received lecture fees from Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer Healthcare and Daiichi-Sankyo. Dr. Lip is Consultant for Bayer/Janssen, BMS/Pfizer, Biotronik, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Verseon and Daiichi-Sankyo. Speaker for Bayer, BMS/Pfizer, Medtronic, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi-Sankyo. No fees are directly received personally. Drs. Miyazawa, Ogawa, Mazurek and Shantsila report no competing interests.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0546