2019 年 83 巻 3 号 p. 637-646

2019 年 83 巻 3 号 p. 637-646

Background: A unique dose of prasugrel has been approved exclusively for Japanese patients, but real-world data for prasugrel at that dose in patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD) are limited. Therefore, large-scale, real-world data are needed.

Methods and Results: A 2-year observational study of Japanese patients with IHD undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention and being treated with prasugrel to evaluate safety and effectiveness. This report is an interim analysis of data from case report forms (CRFs) after 3 months. CRFs were collected from 4,270 patients, 4,157 of whom were eligible for the safety and effectiveness analysis sets (mean age, 68.3 years; male, 76.5%). The median treatment period was 112 days, and 92.3% of patients continued treatment with prasugrel. The incidence of non-coronary artery bypass grafting-related bleeding adverse events (AEs) was 3.1%, of which Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) major and minor bleeding accounted for 0.5% and 0.6%, respectively. The most common bleeding AEs were gastrointestinal disorders, which accounted for 43.2% of the sum of “TIMI major and minor bleeding AEs”. The incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was 1.0%, and the cumulative incidence of MACE was 1.4%. The incidence of stent thrombosis was 0.2%.

Conclusions: Interim study results indicated that prasugrel was safe and effective during the early phase of treatment in Japanese patients with IHD in real-world clinical settings.

Heart disease is the second leading cause of death in Japan, accounting for 15.1% of all deaths.1 The estimated number of patients with ischemic heart disease (IHD) in Japan was 779,000 in 2014.2 In 2016, the mortality rates of patients with acute myocardial infarction (MI) and other IHDs were reported to be 28.7 and 27.6 per 100,000 population, respectively.1

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is a major therapeutic intervention for IHD. To prevent recurrent ischemic cardiovascular events after PCI, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with aspirin and a thienopyridine adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-receptor antagonist is recommended.3,4 However, the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel, a 2nd-generation thienopyridine, shows individual variations influenced by the presence of CYP2C19 polymorphisms. The limitations of the antiplatelet effect of clopidogrel,5,6 plus the time to onset of effect prompted the development of a more efficacious and rapid-acting antiplatelet agent. Prasugrel, a new-generation thienopyridine antiplatelet agent developed in Japan, provides a consistent platelet inhibiting effect, irrespective of the CYP2C19 polymorphism.7 The Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TRITON-TIMI) 38, a multinational phase III trial, reported that prasugrel (initial loading dose [LD]/maintenance dose [MD], 60/10 mg) reduced the incidence of ischemic cardiovascular events but increased the risk of major bleeding events compared with clopidogrel (300/75 mg) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).8

Because the risk of bleeding might be higher in Japanese patients, who are often older and have a lower body weight than Western patients, the approved doses of prasugrel in Japan (LD/MD, 20/3.75 mg) were set lower than those in Western countries in consideration of the risks and benefits. The 2 phase III clinical trials conducted in Japan (PRASugrel compared with clopidogrel For Japanese patIenTs with ACS undergoing PCI, PRASFIT-ACS; PRASugrel For Japanese PatIenTs with Coronary Artery Diseases Undergoing Elective PCI, PRASFIT-Elective) confirmed the safety and efficacy of prasugrel at the approved doses in Japan and that the risk of bleeding was acceptable.9,10 In addition, PRASFIT-Practice I was conducted as an observational study in real-world clinical settings including patients who had been excluded from previous phase III clinical trials in Japan such as those with severe cardiac disease or on dialysis, and the results confirmed the safety and effectiveness of short-term prasugrel use in patients with ACS.11 In some other Asian countries, prasugrel is planned to be used at the same doses as in Japan; therefore, the collection and analysis of real-world data of patients with IHD receiving prasugrel may be especially beneficial for clinical practice in those countries.

PRASFIT-Practice II is a 2-year postmarketing observational study aiming to evaluate the long-term safety and effectiveness of prasugrel in patients with IHD in real-world clinical settings. The subjects included high-risk patients with bleeding who had been excluded from clinical trials and for whom safety information is lacking. This is an interim analysis of data from case report forms (CRFs) after 3 months, aiming to evaluate and report the safety and effectiveness of prasugrel in the early phase of treatment in Japanese patients with IHD.

This was a prospective postmarketing observational study of patients with IHD receiving prasugrel (clinical trial registration No.: UMIN000018003). The study was conducted in accordance with Good Postmarketing Study Practice (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Ordinance No. 171, December 20, 2004). The study period was between June 1, 2015 and May 31, 2018. The observation period was scheduled to be at least 2 years after the start of prasugrel treatment, regardless of treatment completion or discontinuation.

The CRFs of patients who met the inclusion criteria were collected from each participating institution by a continuous prospective surveillance method after obtaining written informed consent from all participants. Inclusion criteria were (1) patients with IHD (ACS [unstable angina pectoris (UAP); non-ST-segment elevation MI, NSTEMI; ST-segment elevation MI, STEMI], stable angina pectoris, and old MI) who had not received prasugrel previously and who required PCI; (2) patients scheduled to undergo PCI within 30 days after starting prasugrel; (3) patients who started prasugrel during the contract period and before May 31, 2016; and (4) patients scheduled to receive long-term treatment with prasugrel. Among the patients for whom CRFs were collected, those who met the following exclusion criteria were excluded from the safety analysis: breach of contract, unavailability of assessment (patients who had not received prasugrel or those who had not undergone safety evaluation), protocol deviations, and withdrawal of consent (no data available).

CRFs were principally collected at 3, 12, and 24 months after the start of prasugrel treatment using an electronic data capture system.

Study TreatmentPrasugrel was administered at the attending physicians’ discretion according to the dosage and administration recommended for adults in the Japanese package insert: oral administration once at a LD of 20 mg on the first day of treatment, and then orally once daily at a MD of 3.75 mg.12 Aspirin (81–100 mg/day, with an initial LD ≤324 mg) should be concurrently administered. Patients receiving prasugrel 3.75 mg for approximately 5 days prior to PCI do not require an initial LD.

Study VariablesData obtained from the CRFs after 3 months included: patient background, clinical characteristics, administration status of prasugrel and concomitant drugs, initial coronary angiography findings, initial PCI requiring treatment with prasugrel, elective PCI after the start of prasugrel treatment, adverse events (AEs) including bleeding, and cardiovascular events.

Cardiovascular events and bleeding were classified according to the criteria described by Nakamura et al.11 Cardiovascular events were classified as death (cardiovascular death/noncardiovascular death), nonfatal MI, readmission due to angina pectoris cerebral stroke (ischemic stroke excluding transient ischemic attack [TIA], and nonischemic stroke), revascularization, and stent thrombosis (ST: defined as definite or probable according to the Academic Research Consortium). Non-coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)-related bleeding was classified as major bleeding (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] major bleeding), minor bleeding (TIMI minor bleeding), clinically relevant bleeding, and other bleeding (excluding bleeding usually observed during invasive procedures including PCI). AEs and adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were classified and counted by System Organ Class (SOC) and Preferred Term (PT) as defined by MedDRA/J version 20.1.

Safety and EffectivenessThe safety outcomes assessed were the incidences of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs and all AEs in the CRFs after 3 months. For non-CABG-related bleeding AEs, cumulative incidences of “all bleeding”, “TIMI major or minor bleeding”, and “TIMI major bleeding” were analyzed. The outcomes assessed for effectiveness were the incidence of cardiovascular events in the CRFs after 3 months. In addition, the cumulative incidences of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE: cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, nonfatal ischemic stroke, and ST) and ST during prasugrel treatment were analyzed. The observation period was set to 250 days as the maximum period to obtain a sufficient number of cases for the calculation of cumulative incidence.

Statistical AnalysisData collected from the CRFs were categorized into 3 groups: total, ACS (STEMI, NSTEMI, and UAP), and non-ACS. Continuous variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD). Incidences were calculated for the parameters used to evaluate safety and effectiveness. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify the risk factors for non-CABG-related bleeding AEs and cardiovascular events, which were selected from baseline factors that were thought to be clinically important using an exploratory stepwise regression procedure. The statistical significance level was set at P<0.05. The cumulative incidences of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs and cardiovascular events and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS® System Release 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

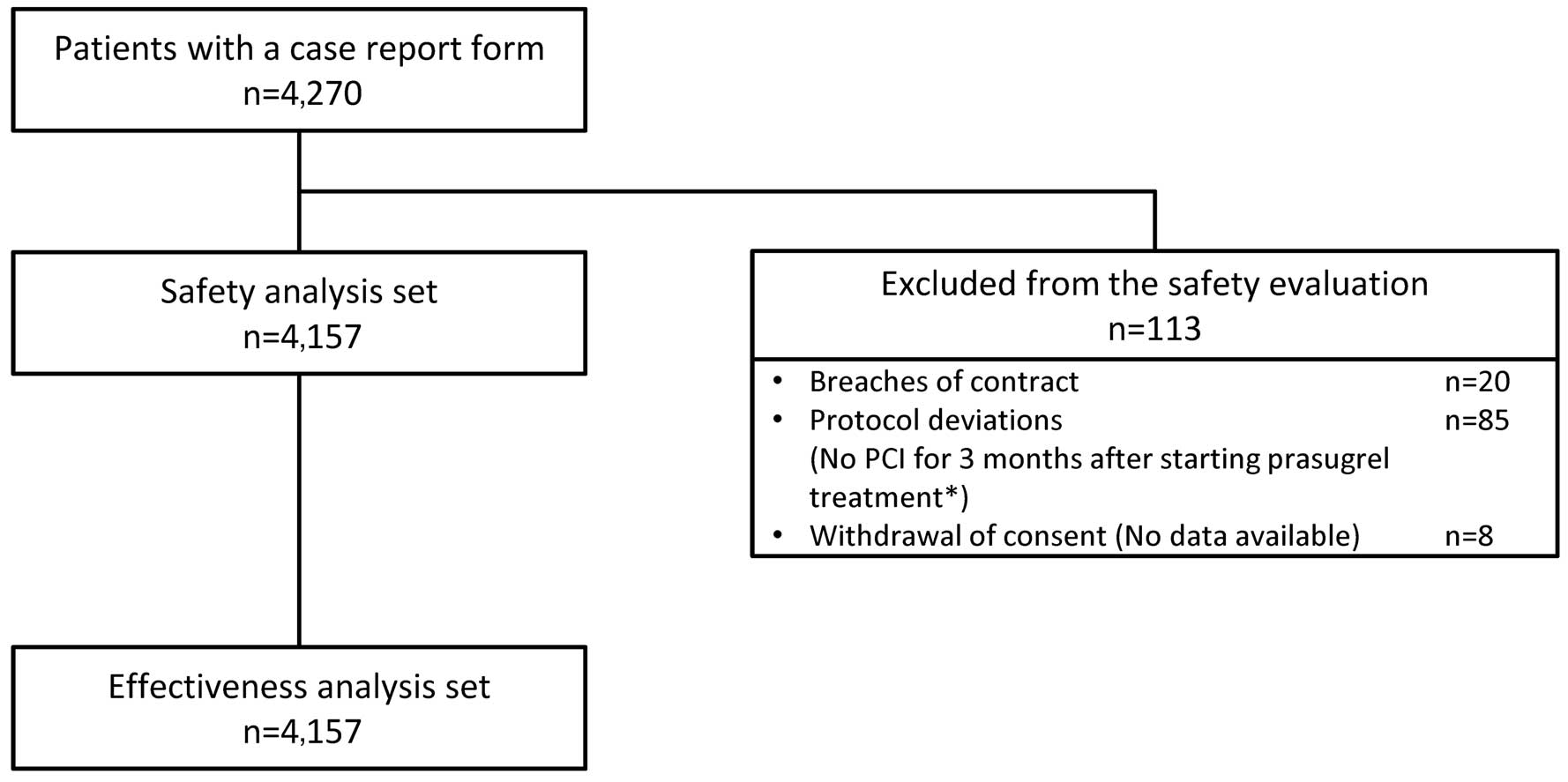

CRFs after 3 months were collected from 4,270 patients at 333 institutions and locked (Figure 1). Of the 4,270 patients, 113 were excluded because of breaches of contract (n=20), protocol deviations (n=85), and withdrawal of consent (n=8); thus, 4,157 patients were included in the safety analysis set and the effectiveness analysis set.

Patient disposition in PRASFIT-Practice II. *Patients who did not undergo scheduled PCI within 30 days after initiation of prasugrel were included in the analysis when they underwent PCI within 3 months after the start of study treatment. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

The baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients in the safety analysis set (n=4,157) are shown in Table 1. Among all patients, the proportions of those aged ≥75 years, those with low body weight (≤50 kg), and those aged ≥85 years were 31.1%, 13.5%, and 5.6%, respectively. Past history included angina pectoris (18.9%), MI (8.8%), ischemic stroke (5.2%), TIA (1.0%), and cerebral hemorrhage (1.1%). Concomitant diseases included hypertension (71.3%), dyslipidemia (67.2%), and diabetes mellitus (38.7%). Regarding the proportion of patients who met the exclusion criteria of PRASFIT-ACS10 or PRASFIT-Elective,9 2.4% of patients were on dialysis, and 3.5% of ACS patients were classified as Killip Class IV.

| Total, n (%) (N=4,157) |

ACS, n (%) (N=2,376) |

Non-ACS, n (%) (N=1,781) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3,180 (76.5) | 1,857 (78.2) | 1,323 (74.3) |

| Age (years) | |||

| ≥75 | 1,293 (31.1) | 674 (28.4) | 619 (34.8) |

| Mean±SD | 68.3±11.2 | 66.8±12.0 | 70.1±9.7 |

| Body weight (kg) | |||

| ≤50 | 561 (13.5) | 322 (13.6) | 239 (13.4) |

| Mean±SD | 63.9±13.0 | 64.2±13.3 | 63.5±12.6 |

| Medical history and complications | |||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 366 (8.8) | 170 (7.2) | 196 (11.0) |

| Prior ischemic stroke | 215 (5.2) | 103 (4.3) | 112 (6.3) |

| Prior cerebral hemorrhage | 46 (1.1) | 24 (1.0) | 22 (1.2) |

| Prior PCI | 596 (14.3) | 237 (10.0) | 359 (20.2) |

| Prior CABG | 73 (1.8) | 25 (1.1) | 48 (2.7) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 263 (6.3) | 100 (4.2) | 163 (9.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 250 (6.0) | 110 (4.6) | 140 (7.9) |

| On dialysis | 98 (2.4) | 28 (1.2) | 70 (3.9) |

| Peptic ulcer | 134 (3.2) | 72 (3.0) | 62 (3.5) |

| Risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 2,965 (71.3) | 1,641 (69.1) | 1,324 (74.3) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2,795 (67.2) | 1,603 (67.5) | 1,192 (66.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,610 (38.7) | 848 (35.7) | 762 (42.8) |

| Current smoker | 1,105 (26.6) | 783 (33.0) | 322 (18.1) |

| Diagnosis | |||

| STEMI | 1,334 (32.1) | 1,334 (56.1) | – |

| NSTEMI | 312 (7.5) | 312 (13.1) | – |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 730 (17.6) | 730 (30.7) | – |

| Stable angina pectoris | 1,530 (36.8) | – | 1,530 (85.9) |

| Old myocardial infarction | 159 (3.8) | – | 159 (8.9) |

| Other | 92 (2.2) | – | 92 (5.2) |

| Antithrombotic agent* | |||

| Prasugrel+aspirin | 3,872 (93.1) | 2,253 (94.8) | 1,619 (90.9) |

| Prasugrel+aspirin+VKA | 74 (1.8) | 23 (1.0) | 51 (2.9) |

| Prasugrel+aspirin+DOAC | 95 (2.3) | 31 (1.3) | 64 (3.6) |

| Prasugrel+NSAIDs (without aspirin) | 71 (1.7) | 30 (1.3) | 41 (2.3) |

| Concomitant drugs | |||

| PPI | 2,016 (48.5) | 1,077 (45.3) | 939 (52.7) |

| Type of stent | |||

| DES | 3,872 (93.1) | 2,197 (92.5) | 1,675 (94.0) |

| Puncture site | |||

| Radial artery | 2,810 (67.6) | 1,458 (61.4) | 1,352 (75.9) |

| Killip classification | |||

| Class I | – | 1,860 (78.3) | – |

| Class II | – | 327 (13.8) | – |

| Class III | – | 61 (2.6) | – |

| Class IV | – | 83 (3.5) | – |

*Only major regimens are shown. There are also cases of combinations of drugs other than those described here and cases of combined therapy not being administered. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; DES, drug-eluting stent; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; IHD, ischemic heart disease; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; VKA, warfarin.

Regarding concomitant drugs at the time of starting the treatment, 93.1% of all patients were on DAPT with prasugrel and aspirin, and 4.1% of all patients were on triple therapy with DAPT and anticoagulants (warfarin potassium [VKA] or direct-acting oral anticoagulants [DOAC]).

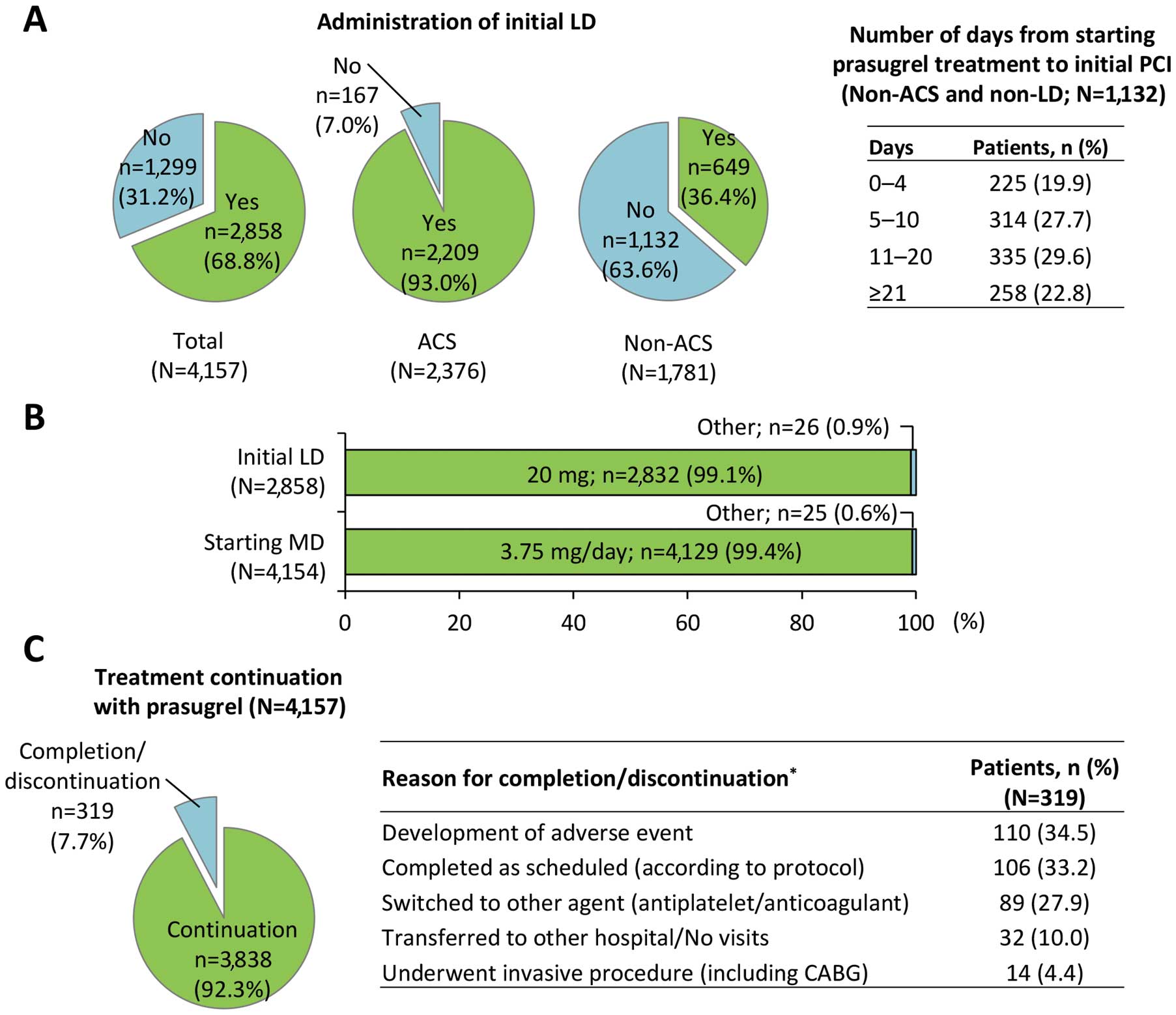

Treatment Status and DiscontinuationsTreatment status of prasugrel and discontinuations are shown in Figure 2. An initial LD was administered to 68.8% of all patients (93.0% for ACS; 36.4% for non-ACS) (Figure 2A). Of the patients with non-ACS, 63.6% were not given the initial LD, and the proportion of patients for whom maintenance therapy was started at least 5 days prior to the initial PCI was 80.1%. The initial LD was 20 mg in 99.1% of patients (Figure 2B), and the initial LD was given before the PCI in 80.4% of patients. In 99.4% of patients, the starting MD was 3.75 mg/day. A total of 319 patients completed or discontinued the treatment, and 92.3% (93.1% for ACS; 91.4% for non-ACS) of patients continued their use of prasugrel (Figure 2C). The most common reasons for completion/discontinuation were AEs (34.5%), followed by scheduled completion (33.2%). The median (range) treatment period was 112 (1–741) days.

Treatment status of prasugrel. (A) Administration of initial LD in all patients, ACS patients, and non-ACS patients, and the number of days from starting prasugrel treatment to initial PCI in non-ACS patients (non-LD). (B) Initial LD and starting MD. (C) Treatment continuation and reasons for discontinuation or completion (*multiple answers allowed). ACS, acute coronary syndrome; LD, loading dose; MD, maintenance dose; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

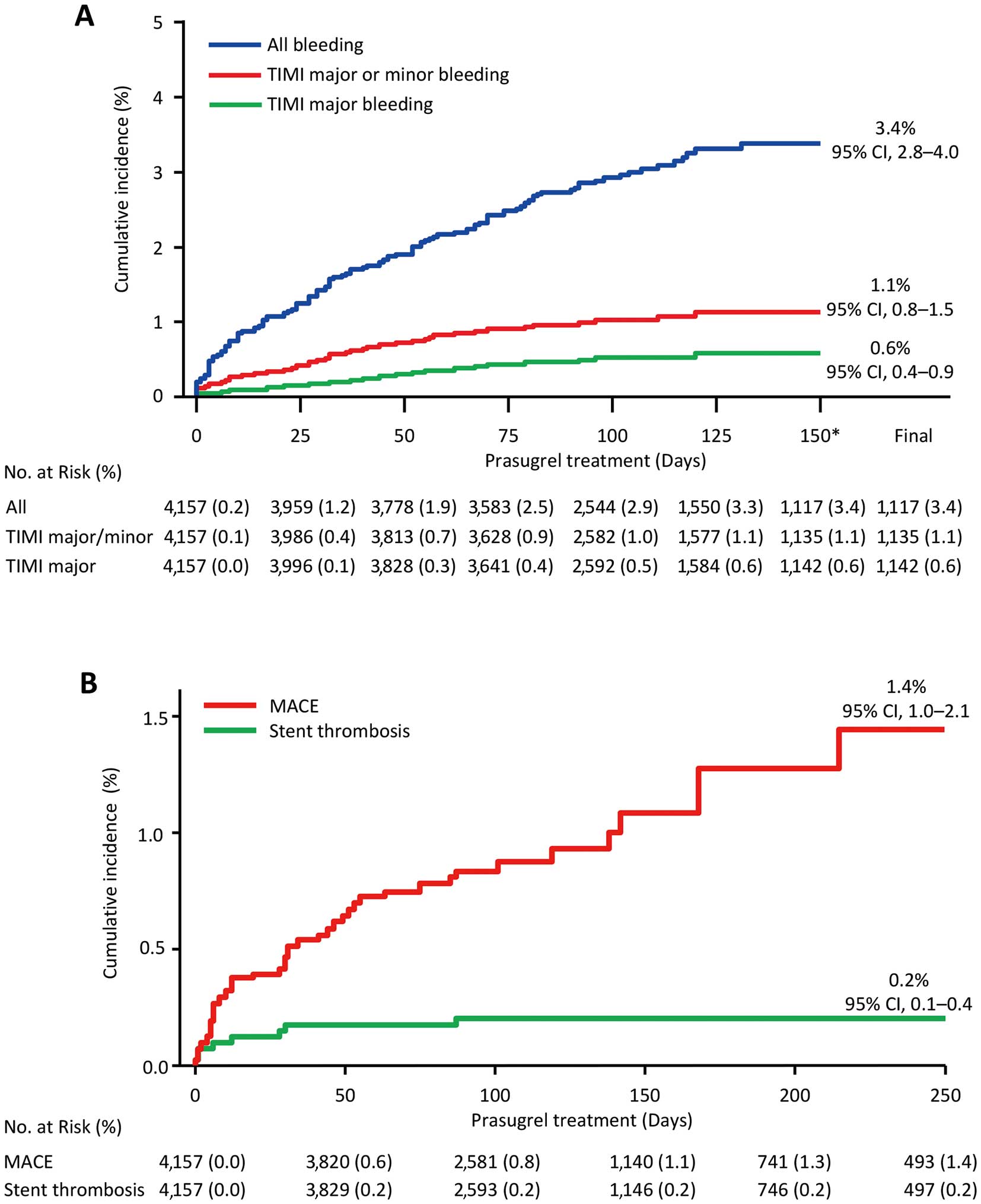

Safety The incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs during the treatment period in all patients was 3.1% (129/4,157), with a similar incidence between the ACS and non-ACS groups (3.1% for both). Bleeding was classified according to the TIMI criteria: major and minor bleeding was observed in 0.5% (n=21) and 0.6% (n=23) of all patients, respectively (Table 2). In the 21 patients with “TIMI major bleeding”, the most common AE was gastrointestinal disorders (33.3%, n=7; Figure 3). In the 44 patients with “TIMI major or minor bleeding”, the most common AE was gastrointestinal disorders (43.2%, n=19), which was the major bleeding AE. In addition, the cumulative incidences of “all bleeding”, “TIMI major or minor bleeding”, and “TIMI major bleeding” during the treatment with prasugrel (150 days) were 3.4% (95% CI, 2.8–4.0), 1.1% (95% CI, 0.8–1.5), and 0.6% (95% CI, 0.4–0.9), respectively (Figure 4A).

| Bleeding classification | Patients, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=4,157) |

ACS (N=2,376) |

Non-ACS (N=1,781) |

|

| All bleeding | 129 (3.1) | 73 (3.1) | 56 (3.1) |

| TIMI major or minor bleeding | 44 (1.1) | 26 (1.1) | 18 (1.0) |

| TIMI major bleeding | 21 (0.5) | 12 (0.5) | 9 (0.5) |

| TIMI minor bleeding | 23 (0.6) | 14 (0.6) | 9 (0.5) |

| Clinically relevant bleeding | 38 (0.9) | 19 (0.8) | 19 (1.1) |

| Other bleeding | 48 (1.2) | 28 (1.2) | 20 (1.1) |

TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Incidence of leading bleeding adverse events during prasugrel treatment. TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Cumulative incidences of bleeding adverse events (AEs), MACE, and stent thrombosis during prasugrel treatment. Cumulative incidences of (A) non-CABG-related bleeding AEs (“all bleeding”, “TIMI major or minor bleeding”, and “TIMI major bleeding”) and (B) MACE, and stent thrombosis estimated by Kaplan-Meier method. The definition of MACE included cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal nonischemic stroke, and stent thrombosis. *Maximum value on the horizontal axis set at 150 days, because the cumulative incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs reached a plateau within 150 days after starting prasugrel treatment. CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Serious non-CABG-related bleeding AEs were observed in 1.0% of all patients (42/4,157). The most common serious bleeding events were subarachnoid hemorrhage (5 events, including 2 traumatic bleeding events), followed by cerebral hemorrhage (4 events, including 1 traumatic bleeding event), cardiac tamponade (3 events), diverticulum intestinal hemorrhagic (3 events), and puncture-site hemorrhage (3 events) (Supplementary Table 1). The common bleeding AEs classified as “clinically relevant bleeding” or “other bleeding” were skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders (22 events), gastrointestinal disorders (16 events), and respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders (12 events) (Supplementary Table 1). The incidences of serious AEs, ADRs, and serious ADRs were 5.2% (218/4,157), 4.3% (179/4,157), and 1.1% (47/4,157), respectively (Supplementary Table 2).

Multivariate analyses were performed to identify factors associated with all non-CABG-related bleeding AEs. The 5 factors significantly associated with non-CABG-related bleeding AEs in the CRFs after 3 months were: female sex, complication of cerebrovascular disorder, complication of anemia, triple therapy with DAPT and anticoagulants (VKA or DOAC) at baseline, and concomitant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) at baseline (Table 3A).

| Factor | P value | HR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Factors associated with “all bleeding” | |||

| Female sex | 0.0117 | 1.615 | 1.112–2.345 |

| Cerebrovascular disorders* | 0.0197 | 1.916 | 1.109–3.310 |

| Anemia | <0.0001 | 3.183 | 1.819–5.570 |

| Concomitant medications (aspirin+VKA or DOAC) | 0.0006 | 2.694 | 1.534–4.730 |

| Concomitant medications (NSAIDs) | 0.0456 | 2.329 | 1.017–5.335 |

| B. Factors associated with cardiovascular events | |||

| Cerebrovascular disorders | 0.0070 | 2.418 | 1.273–4.593 |

| Concomitant medication (PPI) | 0.0151 | 1.761 | 1.116–2.778 |

Multivariate analysis. *Breakdown of cerebrovascular disorders (n=239, 249 events): ischemic stroke, 74.3%; carotid artery disease, 11.6%; cerebral arterial aneurism, 3.6%; transient ischemic attack, 3.2%; intracranial hemorrhage, 2.4%. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Effectiveness The incidences of cardiovascular events during prasugrel treatment are shown in Table 4. In the effectiveness analysis set, the incidence of all-cause death was 0.7% (28/4,157) and that of MACE was 1.0% (n=40). The most commonly observed MACE was cardiovascular death (n=16). The cumulative incidence of MACE during the treatment with prasugrel (250 days) was 1.4% (95% CI, 1.0–2.1) (Figure 4B). The cumulative incidence of ST was 0.2% (95% CI, 0.1–0.4), and most events were observed within less than 50 days after the start of prasugrel treatment. Multivariate analyses were performed to identify factors associated with cardiovascular events. Cerebrovascular disorders and concomitant use of proton pump inhibitors (PPI) were identified as factors associated with cardiovascular events (Table 3B).

| Cardiovascular event | Total, n (%) (N=4,157) |

ACS, n (%) (N=2,376) |

Non-ACS, n (%) (N=1,781) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All deaths | 28 (0.7) | 15 (0.6) | 13 (0.7) |

| Cardiovascular deaths, (a) | 16 (0.4) | 9 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) |

| Noncardiovascular deaths | 12 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) |

| Nonfatal myocardial infarction, (b) | 10 (0.2)* | 6 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) |

| Nonfatal stroke | 17 (0.4) | 10 (0.4) | 7 (0.4) |

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke, (c) | 11 (0.3) | 6 (0.3) | 5 (0.3) |

| Nonfatal nonischemic stroke | 6 (0.1) | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) |

| Readmission due to angina pectoris | 21 (0.5)* | 17 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) |

| Revascularization | 33 (0.8)* | 24 (1.0) | 9 (0.5) |

| Stent thrombosis, (d) | 8 (0.2)* | 8 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| MACE, (a)+(b)+(c)+(d) | 40 (1.0) |

*Includes patients who developed events during prasugrel cessation (nonfatal myocardial infarction, n=2; readmission due to angina pectoris, n=1; revascularization, n=2; stent thrombosis, n=1). IHD, ischemic heart disease; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular event.

This report if of an interim analysis of a postmarketing observational study of prasugrel in Japanese patients with IHD based on data collected from CRFs after 3 months to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of prasugrel in real-world clinical settings. This study included a relatively large patient population (n=4,157) that reflected real-world clinical practice, including a patient population at high risk for bleeding (patients on dialysis and those with severe ACS [Killip Class IV], history of cerebral infarction or TIA, and concomitant use of anticoagulants) that has been excluded in previous clinical trials (PRASFIT-ACS, PRASFIT-Elective).9,10 In the interim analysis of the early phase of treatment, prasugrel did not increase the risk of safety concerns, including non-CABG-related bleeding AEs and cardiovascular events, compared with previous reports, and there were no new risks identified.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients in this study were similar to those in PRASFIT-Practice I, a short-term postmarketing study of patients with ACS.11 The proportions of older patients (aged ≥75 years) and patients with low body weight (≤50 kg) were higher in this study (31.1% and 13.5%, respectively) than in the 2 approved clinical trials of PRASFIT-ACS (24.1% and 12.4%, respectively) and PRASFIT-Elective (23.2% and 9.2%, respectively),9,10 and thus this study included more patients with a higher bleeding risk than in the clinical trials. Similar to the patients in PRASFIT-Practice I, 99% or more of patients in this study received a LD/MD of 20/3.75 mg. Most patients received an initial LD prior to PCI. Of the non-ACS patients who did not receive the initial LD, 80.1% received the MD for at least 5 days prior to the initial PCI, which was considered attributable to the following instructions in the package insert of prasugrel in Japan: “An initial LD is not required when 3.75 mg of prasugrel has been administered for approximately 5 days prior to PCI.” The treatment continuation rate was 92.3%, and the rates were similar between the ACS (93.1%) and non-ACS (91.4%) groups. In PRASFIT-Practice I, nearly 70% of prasugrel treatment completion or discontinuation occurred, because of a restriction of the treatment duration during the first year after its launch (part of the observation period of the study).11 This study first confirmed the high tolerability of prasugrel (LD/MD, 20/3.75 mg) in real-world clinical settings.

The incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs was similar between ACS and non-ACS patients. Although the risk of bleeding is generally higher in patients with ACS, those with relatively low severity were eligible for inclusion in the study (patients who were scheduled to receive long-term treatment and those who provided written informed consent). Because this report is an interim analysis, we will continue to carefully observe the difference in bleeding rates between ACS and non-ACS patients until the final evaluation (at 2 years). The incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs was lower than that in PRASFIT-Practice I (6.4%), PRASFIT-ACS (49.8%), and PRASFIT-Elective (38.1%), although direct comparison is impossible because of the differences in patient backgrounds and observation periods.9–11 One possible reason for the lower incidence of non-CABG-related bleeding AEs in the present study compared with the clinical trials is that bleeding events usually observed during invasive procedures, including PCI, were excluded in this study but included in the clinical trials. TRITON-TIMI 38 reported that the incidence of non-CABG-related “TIMI major bleeding” was significantly higher with prasugrel (2.4%) than with clopidogrel (1.8%). However, the incidence of “TIMI major bleeding” in this study (0.5%), in PRASFIT-Practice I (1.6%), in PRASFIT-ACS (1.9%), and in PRASFIT-Elective (0%) was similar to or lower than that for clopidogrel in TRITON-TIMI 38.8–11 Despite the risk of bleeding being reportedly higher in Japanese patients than in Western patients, this study showed that the incidence of “TIMI major bleeding” was similar or lower than that in Western patients. One possible reason for the low incidence of “TIMI major and minor bleeding AEs” was a decrease in bleeding as a complication of PCI because of recent advances in medical treatment, particularly advances in PCI treatment.

The results reconfirmed that the approved dose was safe for Japanese patients in real-world clinical settings. The most common “TIMI major or minor bleeding AEs” in this study were gastrointestinal disorders, which was similar to the bleeding events observed in PRASFIT-Practice I. The categories of “clinically relevant bleeding” and “other bleeding” observed in this study were similar to the events noted in PRASFIT-Practice I, and there were no new AEs that could be considered clinically important. With reference to the report that analyzed periprocedural bleeding at the puncture site,13 this study also incorporated analysis of puncture-site bleeding, thereby defining periprocedural bleeding as a bleeding event occurring within 3 days after the initial PCI.

An analysis based on that previous report13 revealed 10 (0.24%) puncture-site bleeding AEs in 4,157 patients, including “TIMI minor bleeding” in 2 cases and “other bleeding” in 8 cases in the present study. In both cases of “TIMI minor bleeding” the patient had the puncture site in the femoral artery at the time of the initial PCI. One possible reason for the lower incidence of puncture-site bleeding in this study compared with the clinical trials is that bleeding events usually observed during PCI were less likely to be reported as an AE in the clinical setting. Because the incidence of puncture-site bleeding in the categories of “TIMI major bleeding” or “TIMI minor bleeding” was 0.05%, the number of cases of puncture-site bleeding after the initial PCI among the prasugrel-treated patients was considered to be very small, suggesting that safety problems with PCI were rarely observed.

These findings suggested that prasugrel administered as LD/MD 20/3.75 mg did not increase the risk of bleeding in Japanese patients with IHD, and that the results were acceptable in real-world clinical practice in Japan. This study included many older patients with high bleeding risk (mean age, 68.3 years), so the obtained information is beneficial to practical physicians in Japan, which is becoming an aging society. In South Korea, prasugrel is currently used at the same dosage as in Western countries. The Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry-National Institutes of Health (KAMIR-NIH) study, a cohort study of patients with acute MI and responsive to PCI, reported that the incidence of “TIMI major or minor bleeding” during hospitalization was significantly higher in patients using prasugrel than in those taking clopidogrel.14 These differences in study results between Japan and South Korea suggest that East Asians have a higher risk of bleeding complications compared with Westerners and therefore require a specific dosage adjustment of prasugrel, known as the “East Asian Paradox.”15

Non-CABG-related bleeding AEs were found to be associated with some factors, namely, female sex, complication of cerebrovascular disorder or anemia, triple therapy with DAPT and anticoagulants (VKA or DOAC) at baseline, or concomitant use of NSAIDs. However, these results are from an interim analysis of CRFs after 3 months, and a complete analysis at the end of the 2-year observation period is forthcoming. The bleeding risk factors identified in this study were similar to those in previous reports.16,17 Although the PREdicting bleeding Complications In patients undergoing Stent implantation and subsEquent Dual Anti-Platelet Therapy (PRECISE-DAPT) score18 and the Patterns of Non-Adherence to Anti-Platelet Regimen in Stented Patients (PARIS) registry risk score19 are known as risk assessment tools for bleeding, the factors identified in this study might have to be also assessed in Japanese patients. This study showed that the incidence of bleeding events was generally low in the early phase of treatment with prasugrel at the LD/MD of 20/3.75 mg. However, further treatment strategies, such as dose reduction or monotherapy of prasugrel, could be explored to reduce the risk of bleeding in Japanese patients with complex bleeding risk factors, such as those identified in this study.

The incidence of all cardiovascular events in this study was similar to or less than in PRASFIT-Practice I, and a similar trend was seen in comparison with the previous clinical trials (PRASFIT-ACS and PRASFIT-Elective), although direct comparison was impossible because of differences in patients’ backgrounds and the observation period.8–11 The incidence of MACE in this study was 0.9% (0.9% each for ACS and non-ACS), which was lower than in PRASFIT-ACS (9.4%), PRASFIT-Elective (4.1%), and PRASFIT-Practice I (3.1%) when the same definition of MACE (cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, and nonfatal ischemic stroke) was used. ST occurred mainly in the early phase of treatment after PCI (prasugrel treatment period <50 days), and the cumulative incidence during the 250 days of treatment remained low (0.2%). The pivotal study PRASFIT-ACS did not show statistically significant differences in efficacy, because of the limitation in the number of subjects, although prasugrel showed a trend towards similar efficacy in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial despite the dose being one-third of that administered in Western contries.10 The present study reflected real-world clinical practice and included more severe patients than did PRASFIT-ACS; however, the incidence of cardiovascular events in this study was not higher than in PRASFIT-ACS. Our results support the effectiveness of prasugrel at the approved dose in Japan. In this study, cerebrovascular disorders, which are a common risk factor for cardiovascular events, and the concomitant use of PPI were identified as risk factors for cardiovascular events. A possible reason for PPI being a factor associated with cardiovascular events is that patients taking a PPI tend to be in poor general condition; however, because this result was derived from interim analysis data, final analysis data are required to make a definite conclusion.

Study LimitationsThis was an observational study without control groups, and the observation period was short because it is an interim analysis of CRFs after 3 months. Direct comparisons of safety and effectiveness between this study and previous clinical trials were difficult because of differences in the observation period and patients’ backgrounds related to differences in study design and exclusion criteria. Because the bleeding classification and definitions of AEs in the clinical trials were adjusted in this study to reflect those used in real-world clinical settings, some AEs in the clinical trials, such as periprocedural MI caused by creatine kinase-MB increase, were not categorized as AEs in this study. The frequency of bleeding in this study was lower than in the clinical trials because the bleeding AEs classification in the present study excluded bleeding occurring during invasive procedures such as PCI.

This study included aged patients (mean age of nearly 70 years) with high bleeding risk, such as those with ischemic stroke, those on triple therapy with DAPT and anticoagulants (VKA or DOAC), and dialysis patients, all of whom were excluded in previous clinical trials. The results from this study showed that the incidences of “TIMI major bleeding” and “TIMI major or minor bleeding” in the CRFs after 3 months were 0.5% and 1.1%, respectively, and that the incidences of ST (0.2%) and MACE (1.0%) were low. Our results confirmed the safety and effectiveness of prasugrel at the LD/MD of 20/3.75 mg/day in the early phase of treatment in Japanese patients with IHD.

The authors thank all the investigators, staff, and patients who contributed to this postmarketing observational study. The authors also thank Go Kuratomi, PhD, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for providing medical writing assistance, which was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Company, Limited (Tokyo, Japan).

This study was funded by Daiichi Sankyo Company, Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). MN has received remuneration (e.g., lecture fees) from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., and Terumo Corporation; and research funds from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd. and Sanofi K.K. KK has received remuneration (e.g., lecture fees) from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., and Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd.; and scholarship funds from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Pfizer Japan Inc., and Astellas Pharma Inc.TK has received remuneration (e.g., lecture fees) from Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd.; and scholarship funds from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited., Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Astellas Pharma Inc., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd., MSD K.K., Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, EA Pharma Co., Ltd., Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, Eisai Co., Ltd., Sanofi K.K., Pfizer Japan Inc., Torii Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Asahi Kasei Medical Co., Ltd. TI, TS, KS, IU, and SK are employees of Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd.

None.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-18-0956