Abstract

Background:

Infective endocarditis remains associated with substantial mortality and morbidity rates, and the presence of acute heart failure (AHF) compromises clinical results after valve surgery; however, little is known in cardiogenic shock (CGS) patients. This study evaluated the clinical results and risk of mortality in CGS patients after valve surgery.

Methods and Results:

This study enrolled 585 patients who underwent valve surgery for active endocarditis at 14 institutions between 2009 and 2017. Of these patients, 69 (12%) were in CGS, which was defined as systolic blood pressure <80 mmHg and severe pulmonary congestion, requiring mechanical ventilation and/or mechanical circulatory support, preoperatively. The predictors of CGS were analyzed, and clinical results of patients with non-CGS AHF (n=215) were evaluated and compared.

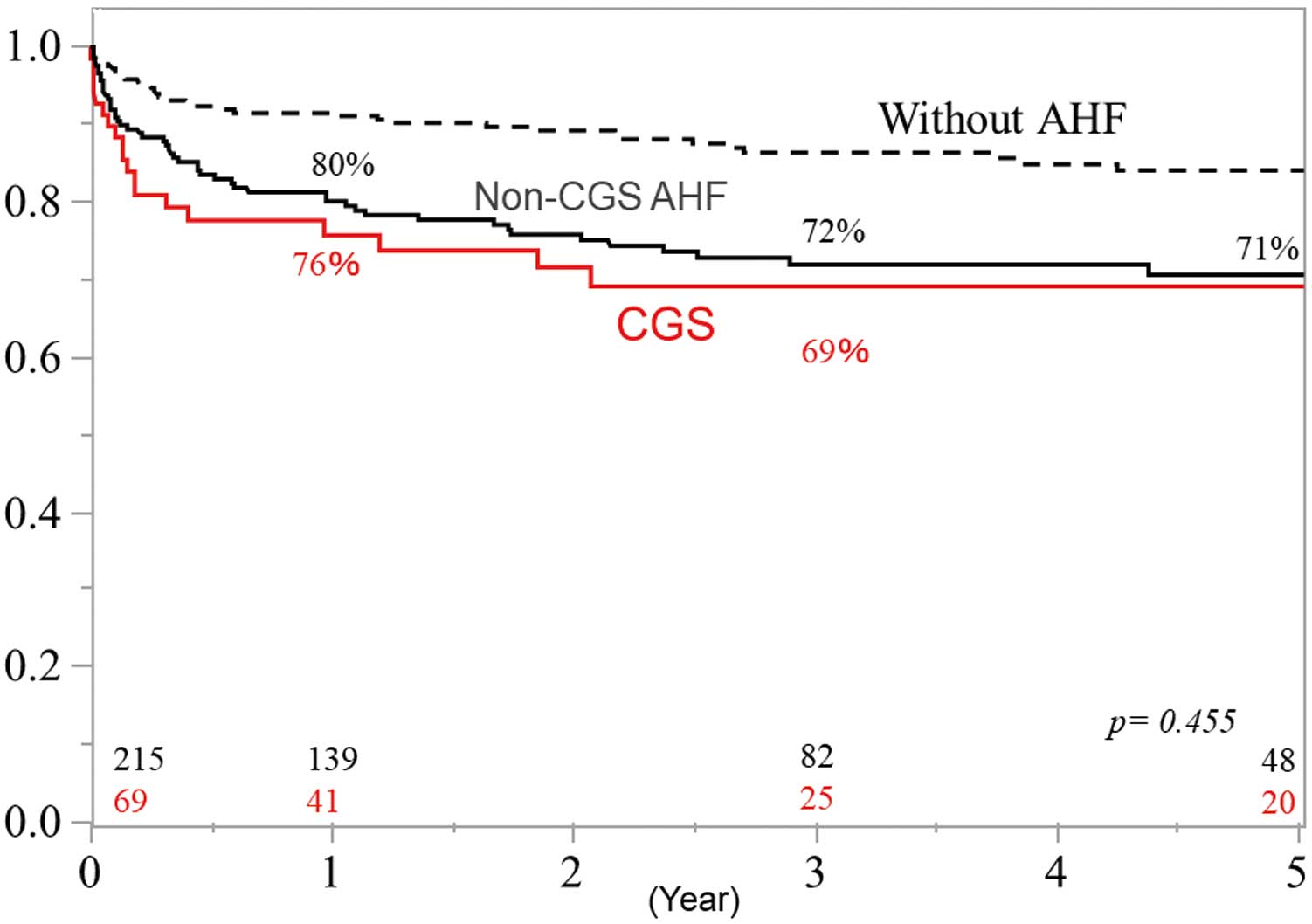

Staphylococcus aureus

infection (odds ratio [OR] 2.19; P=0.044), double valve involvement (OR 3.37; P=0.003), and larger vegetation (OR 1.05; P=0.036) were risk factors for CGS. Hospital mortality occurred in 27 (13%) non-CGS AHF patients and in 15 (22%) CGS patients (P=0.079). Overall survival at 1 and 5 years in CGS patients was 76% and 69%, respectively, and there were no significant differences in overall survival compared with non-CGS AHF patients (P=1.000).

Conclusions:

Clinical results after valve surgery in CGS patients remain challenging; however, mid-term results were equivalent to those of non-CGS AHF patients.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is associated with substantial mortality and morbidity rates. Among the various complications of IE, acute heart failure (AHF) reportedly occurs in 40% of cases.1,2

Current guidelines recommend early surgical intervention for patients with AHF,3–5

especially cardiogenic shock (CGS) patients undergoing emergency surgery. Although several previous reports stated that the presence of AHF compromised clinical results after valve surgery,1,6,7

little is known about such results in CGS patients. Therefore, in the present multicenter study we evaluated the risk factors for CGS in IE patients as well as the clinical results and risk of mortality after valve surgery in CGS IE patients.

Methods

Patients

The present retrospective multicenter study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Osaka University Hospital, and the use of the Osaka Cardiovascular Research (OSCAR) Group database was approved by each affiliated hospital.

Detailed records were obtained for patients who underwent valve surgery for active left-sided IE between 2009 and 2017 in 14 affiliated hospitals. Left-sided active IE was defined as IE that involved the aortic or mitral valve and required antibiotic therapy until surgery. Patients with healed IE or IE that involved only the right side valve were excluded from the study. Between 2009 and 2017, 585 patients underwent valve surgery for left-sided active IE. Of these patients, 69 (12%) were in refractory CGS before valve surgery. We analyzed predictors of CGS in all 585 patients. In addition, the baseline characteristics of and compared with CGS patients with non-CGS AHF (n=215) were obtained and compared with CGS patients.

Because the use of the OSCAR group database had been approved, the need for informed consent was waived by each participating hospital’s ethics committee.

Surgery and Postoperative Treatment for Active Endocarditis

The day of IE diagnosis was defined as the day on which the presence of vegetation was first confirmed using transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiography. In patients without obvious vegetation, the day of diagnosis was defined as the day on which the patient first met modified Duke’s criteria for definitive endocarditis.8

The indications for and details of valve surgery have been described elsewhere.9

Approximately 80% of patients underwent a preoperative systemic computed tomography scan, unless such scans were contraindicated (77% in the non-CGS AHF group, 87% in the CGS group; P=0.889).

Definitions of CGS, Heart Failure, and Other Comorbidities and Complications

In the present study, the presence of CGS was defined as follows: systolic blood pressure <80 mmHg with increasing filling pressure of the left ventricle that required mechanical ventilation and/or mechanical circulatory support (i.e., intra-aortic balloon pump [IABP],10

extracorporeal membranous oxygenation [ECMO]) due to severe acute pulmonary congestion following a collapse of the hemodynamic circulation before the valve surgery. Patients who required mechanical ventilation for neurological disorders and sepsis without an episode of dyspnea, pulmonary congestion, or inotropic support were not included in the CGS group. In addition, patients who required mechanical ventilation for any reason but were extubated after effective medical therapy before the valve surgery were also not considered CGS patients. Meanwhile, non-CGS AHF patients were defined as those with symptomatic heart failure at rest (New York Heart Association Class IV) and/or those who required inotropic support before surgery. Patients requiring only oral or intravenous diuretics without any symptoms of heart failure were not considered to have AHF.

The definitions of other preoperative complications (e.g., heart failure, stroke, and embolism) and postoperative complications (e.g., neurological deterioration and complete atrioventricular [AV] block) have been described elsewhere.9

Mid-term follow-up data were also collected in this study. Mid-term mortality and the definition of each cause have also been described elsewhere.9

Laboratory and Echocardiographic Values

The causative organism was defined as one that was detected in a blood culture or resected valve culture. Vegetation size was determined on the basis of its maximum length. Preoperative laboratory valuables were obtained from the medical records at the time of the endocarditis diagnosis and just before valve surgery. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the following equation:

eGFR=186×(serum creatinine/88.4)−1.154×(age in years)−0.203×0.742 (if female)

Data Collection

Patients eligible for the study were identified using the OSCAR database, and their details were collected by a review of medical records. The operative records of all patients were also reviewed and details of their surgical procedures were collected. Follow-up investigations were performed using the information obtained from patient medical records or telephone contact by a physician in each hospital. In the present study, the median follow-up period was 2.2 (interquartile range [IQR] 0.4–4.9) years.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 12.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, CA, USA). Categorical variables are presented as percentages, whereas continuous data are given as the mean±SD or as the median with IQR after testing for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk W test. Comparisons between 2 groups were performed using the Chi-squared test for categorical variables and Welch’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous variables as appropriate. Comparisons among 3 groups were performed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. All P-values are 2-tailed, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Overall survival and freedom from recurrence of endocarditis rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared between 2 groups using the log-rank test.

Results

The baseline characteristics and preoperative parameters of the 69 CGS patients were analyzed and compared to those of the 215 patients with non-CGS AHF (Table 1,

Supplementary Table 1) and among the 3 groups (Supplementary Table 2). Of the CGS patients, 25 (36%) had

Staphylococcus aureus

infections, and

S. aureus

infection was more prevalent in CGS patients. There was no significant difference in methicillin-resistant

S. aureus

(MSRA) infection between the CGS and non-CGS AHF groups (7 [10%] vs. 18 [8%], respectively; P=0.631). Aortic and/or mitral annular abscess were present in 55 patients (26%) in the non-CGS AHF group and in 23 patients (33%) in the CGS group (P=0.209). There was also no significant difference in prosthetic valve endocarditis between the non-CGS AHF and CGS groups (39 [18%] vs. 13 [19%], respectively; P=0.86). Fifteen patients (22%) were on chronic hemodialysis preoperatively. Although the mean ejection fraction and systolic blood pressure were similar between the 2 groups, the median left ventricular dimension was significantly smaller and the mean heart rate was higher in CGS patients. Five (7%) patients had an abnormal intracardiac shunt (aorta-right ventricle, 2; aorta-right atrium, 2; aorta-left ventricle, 1); the prevalence of abnormal intracardiac shunt was significantly higher in CGS patients than in non-CGS AHF patients and patients without AHF. Preoperatively, 6 (9%) patients required an IABP and 2 (3%) required ECMO.

Table 1.

Baseline and Preoperative Characteristics in Patients With CGS and Those With Non-CGS AHF

| |

Non-CGS AHF

(n=215) |

CGS

(n=69) |

P-value |

| Baseline characteristics |

| Age (years) |

66 [57–71] |

67 [54–75] |

0.942 |

| Male |

139 (65) |

36 (51) |

0.047 |

| Body surface area (m2) |

1.61±0.21 |

1.54±0.19 |

0.164 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) |

22.3 [18.7–25.6] |

21.1 [18.4–23.0] |

0.320 |

| Bacterial species |

| Positive blood culture |

158 (73) |

52 (75) |

0.875 |

| Staphylococcus sp. |

77 (36) |

32 (46) |

0.121 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

48 (22) |

25 (36) |

0.027 |

| MRSA |

18 (8) |

7 (10) |

0.631 |

| Streptococcus sp. |

63 (29) |

21 (30) |

0.880 |

| Comorbidities |

| Atrial fibrillation |

34 (16) |

13 (19) |

0.578 |

| Hemodialysis |

22 (10) |

15 (22) |

0.022 |

| Hypertension |

67 (31) |

15 (22) |

0.169 |

| Diabetes |

45 (21) |

12 (17) |

0.606 |

| Antiplatelet therapy |

38 (18) |

14 (20) |

0.597 |

| Anticoagulation therapy |

32 (15) |

11 (16) |

0.848 |

| Affected valves |

| Aortic valve |

117 (54) |

35 (51) |

0.678 |

| Mitral valve involvement |

135 (63) |

51 (72) |

0.110 |

| Double valve |

37 (17) |

17 (25) |

0.216 |

| Prosthetic valve endocarditis |

39 (18) |

13 (19) |

0.86 |

| Annular abscess |

55 (26) |

23 (33) |

0.209 |

| Echocardiographic parameters |

| LVDd (mm) |

54 [50–61] |

52 [47–58] |

0.009 |

| LVDs (mm) |

35 [31–41] |

32 [25–37] |

0.018 |

| EF (%) |

64 [55–70] |

67 [55–76] |

0.237 |

| Systolic tricuspid pressure gradient (mmHg) |

39 [28–49] |

40 [26–56] |

0.570 |

| Abnormal intra-cardiac shunt |

6 (3) |

5 (7) |

0.143 |

| Maximum length of vegetation (mm) |

12 [9–19] |

15 [10–20] |

0.124 |

| Hemodynamic parameters just before surgery |

| IABP |

– |

6 (9) |

|

| ECMO |

– |

2 (3) |

|

| Heart rate (beats/min) |

86 [75–96] |

100 [85–109] |

0.018 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) |

113 [99–127] |

117 [95–138] |

0.356 |

| Embolism |

| Extremities |

11 (5) |

3 (4) |

>0.999 |

| Spleen |

21 (10) |

13 (19) |

0.055 |

| Kidney |

9 (4) |

5 (7) |

0.339 |

| Brain |

74 (34) |

21 (30) |

0.562 |

| Intracranial hemorrhagic lesion |

23 (11) |

12 (17) |

0.146 |

| Duration between diagnosis and surgery |

6 [2–19] |

2 [0–10] |

0.431 |

| EuroSCORE II at the time of diagnosis |

4.9 [2.9–11.9] |

20.2 [13.7–31.0] |

<0.001 |

Data are given as the mean±SD, n (%), or median [interquartile range]. AHF, acute heart failure; CGS, cardiogenic shock; ECMO, extracorporeal membranous oxygenation; EF, ejection fraction; IABP, intra-aortic balloon pump; LVDd, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVDs, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; MRSA, methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

The risk factors for CGS were analyzed in 585 patients (Table 2). Univariate analysis revealed that female sex,

S. aureus

infection, hemodialysis, double valve involvement (both mitral and aortic), and large vegetation were risk factors for CGS. Multivariate analysis showed that

S. aureus

infection (odds ratio [OR] 2.19; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.02–4.54; P=0.044), double valve involvement (OR 3.37; 95% CI 1.55–7.10; P=0.003), and large vegetation (OR 1.05; 95% CI 1.00–1.10; P=0.036) were independent risk factors for CGS.

Table 2.

Predictors of Cardiogenic Shock in 585 Endocarditis Patients

| |

Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

| OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Baseline characteristics |

| Age |

1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

0.183 |

|

|

| Male sex |

0.51 (0.31–0.86) |

0.011 |

0.65 (0.32–1.32) |

0.234 |

| Bacterial species |

| Positive blood culture |

0.96 (0.54–1.76) |

0.884 |

|

|

| Staphylococcus sp. |

2.19 (1.31–3.65) |

0.003 |

|

|

| Staphylococcus aureus |

2.62 (1.51–4.47) |

0.001 |

2.19 (1.02–4.54) |

0.044 |

| MRSA |

1.77 (0.69–3.97) |

0.196 |

|

|

| Streptococcus sp. |

0.71 (0.41–1.21) |

0.224 |

|

|

| Comorbidities |

| Atrial fibrillation |

1.61 (0.81–3.03) |

0.155 |

|

|

| Hemodialysis |

2.91 (1.48–5.47) |

0.001 |

2.04 (0.86–4.53) |

0.102 |

| Hypertension |

0.64 (0.34–1.14) |

0.148 |

|

|

| Diabetes |

0.80 (0.39–1.49) |

0.934 |

|

|

| Affected valves |

| Aortic valve |

1.25 (0.76–2.07) |

0.384 |

|

|

| Mitral valve involvement |

1.35 (0.78–2.41) |

0.284 |

|

|

| Double valve involvement |

2.58 (1.37–4.69) |

0.004 |

3.37 (1.55–7.10) |

0.003 |

| Prosthetic valve endocarditis |

1.00 (0.51–1.85) |

0.993 |

|

|

| Annular abscess |

1.45 (0.81–2.62) |

0.209 |

|

|

| Echocardiographic parameters |

| LVDd |

0.97 (0.94–1.00) |

0.078 |

0.98 (0.93–1.02) |

0.308 |

| EF |

1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

0.627 |

|

|

| Maximum length of vegetation |

1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

0.012 |

1.05 (1.00–1.10) |

0.036 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

The surgical results of 69 CGS patients are detailed and compared with those of 215 non-CGS AHF patients in

Table 3. The comparison among 3 groups is given in

Supplementary Table 3. The EuroSCORE II and JapanSCORE just before surgery were 21.9% (range 13.6–31.1%) and 24.6% (range 19.4–29.8%), respectively, in CGS patients. Of the CGS group, 35 aortic valve and 51 mitral valve surgeries were performed. Aortic annular patch repair was performed in 36 (31%) and 12 (34%) patients in the non-CGS AHF and CGS groups, respectively (P=0.717). For the mitral valve, replacement rather than repair was preferred in CGS patients compared with non-CGS AHF patients. Similarly, CGS patients required annular patch repair more frequently than non-CGS AHF patients. There were no operations using homografts in the present study. Furthermore, operative time was significantly longer in CGS patients and they required more platelet products.

Table 3.

Operative Results in Patients With CGS and Those With Non-CGS AHF

| |

Non-CGS AHF

(n=215) |

CGS

(n=69) |

P-value |

| EuroSCORE II just before surgery |

4.8 [2.9–11.2] |

21.9 [13.6–31.1] |

<0.001 |

| Japan SCORE just before surgery |

17.7 [14.1–21.8] |

24.6 [19.4–29.8] |

0.037 |

| Aortic valve (n=268) |

n=117 |

n=35 |

|

| Vegetectomy |

1 (1) |

0 (0) |

>0.999 |

| Valve replacement |

116 (99) |

35 (100) |

|

| Bioprosthetic valve |

86 (74) |

30 (86) |

0.178 |

| Mechanical valve |

30 (26) |

5 (14) |

|

| Aortic root surgery |

9 (8) |

8 (23) |

0.028 |

| Annular patch repair |

36 (31) |

12 (34) |

0.717 |

| Mitral valve (n=397) |

n=135 |

n=51 |

|

| Valve repair |

43 (32) |

9 (18) |

0.068 |

| Valve replacement |

92 (68) |

42 (82) |

|

| Bioprosthetic valve |

66 (72) |

33 (79) |

0.526 |

| Mechanical valve |

26 (28) |

9 (21) |

|

| Annular patch repair |

6 (4) |

9 (18) |

0.032 |

| Required CABG |

12 (6) |

6 (9) |

0.395 |

| Required double valve surgery |

37 (17) |

17 (25) |

0.216 |

| Required annular reconstruction |

41 (19) |

21 (30) |

0.064 |

| Operative time and transfusion |

| Operative time (min) |

319 [287–520] |

391 [287–520] |

0.039 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (min) |

173 [134–252] |

195 [152–285] |

0.067 |

| Aortic clamp time (min) |

128 [90–186] |

145 [106–206] |

0.122 |

| Platelet transfusion (units) |

0 [0–20] |

20 [18–40] |

<0.001 |

| Complications |

| Required ECMO |

5 (2) |

5 (7) |

0.067 |

| Required IABP |

8 (4) |

10 (14) |

0.003 |

| Neurological deterioration |

10 (5) |

8 (12) |

0.049 |

| Mediastinitis |

5 (2) |

2 (3) |

0.679 |

| Required CVVHD |

35 (16) |

24 (35) |

0.002 |

| Complete AV block |

7 (3) |

5 (7) |

0.172 |

| Intubation duration (days) |

1 (1–3) |

5 (3–9) |

0.007 |

| Duration of i.v. antibiotics (days) |

28 [21–40] |

35 [25–45] |

0.064 |

| Hospital stay (days) |

39 [26–61] |

48 [32–74] |

0.252 |

| Hospital mortality |

27 (13) |

15 (22) |

0.079 |

| Reason for in-hospital death |

| Heart failure |

5 (2) |

5 (7) |

0.067 |

| Organ failure |

14 (7) |

10 (14) |

0.047 |

| Refractory infection |

8 (4) |

4 (6) |

0.494 |

| Cerebrovascular accident |

5 (2) |

0 (0) |

0.340 |

Unless indicated otherwise, data are given as n (%) or median [interquartile range]. AV, atrioventricular; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CVVHD, continuous venovenous hemodialysis. Other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Postoperatively, 3 (4%) patients required both ECMO and IABP support for postcardiotomy shock, 2 (3%) required ECMO only, and 7 (10%) required IABP only. Neurological deterioration was seen in 8 (12%) patients. Of these patients, 3 (4%) developed postoperative cerebral hemorrhage, 2 (3%) developed a subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 2 (3%) developed cerebral infarction. However, there were no cerebrovascular accident-related deaths among these patients. The requirement for continuous venovenous hemodialysis (CVVHD) was more prevalent in patients with CGS than non-CGS AHF (16% vs. 35%, respectively; P=0.0002). Five of 69 (12%) CGS patients had a postoperative permanent complete AV block, whereas 3 of 27 (11%) patients who underwent aortic valve replacement and 2 of 8 (25%) who underwent the Bentall procedure developed a complete AV block. The duration of mechanical ventilation and intravenous antibiotics treatment were significantly longer in patients with CGS. Hospital mortality was recorded for 27 (13%) non-CGS AHF patients and 15 (22%) CGS patients (P=0.079). The details of these cases are given in

Table 3. Multiorgan failure and heart failure-related deaths were prevalent in CGS compared with non-CGS AHF patients.

Of the 69 CGS patients, 15 (22%) died during hospitalization after valve surgery. We compared the pre- and perioperative characteristics of the 54 patients who survived and the 15 who died, and analyzed ORs for hospital mortality for each parameter (Table 4). Patients who died were significantly older, had a higher prevalence of chronic CVVHD, and had lower preoperative hemoglobin, platelet, and serum total bilirubin levels. There were no significant differences in affected valve, operative time, or surgical procedure between CGS patients who survived and died.

Table 4.

Comparison of Patients Who Survived and Those Who Died

| |

Survived (n=54) |

Deceased (n=15) |

OR (95% CI) |

P-value |

| Baseline characteristics |

| Age (years) |

65 [50–70] |

69 [63–75] |

1.06 (1.01–1.14) |

0.022 |

| Male |

30 (56) |

5 (33) |

0.40 (0.11–1.28) |

0.125 |

| Bacterial species |

| Positive blood culture |

41 (76) |

11 (73) |

0.87 (0.25–3.56) |

0.838 |

| Staphylococcus sp. |

25 (46) |

7 (47) |

1.02 (0.31–3.22) |

0.980 |

| Staphylococcus aureus |

18 (33) |

7 (47) |

1.75 (0.54–5.65) |

0.345 |

| MRSA |

4 (7) |

3 (20) |

3.13 (0.56–16.1) |

0.169 |

| Streptococcus sp. |

18 (33) |

3 (20) |

0.50 (0.10–1.82) |

0.307 |

| Comorbidities |

| Atrial fibrillation |

9 (17) |

4 (27) |

1.82 (0.40–6.79) |

0.396 |

| Hemodialysis |

8 (15) |

7 (47) |

5.03 (1.42–18.3) |

0.013 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

9 (17) |

3 (20) |

1.25 (0.25–4.99) |

0.766 |

| Affected valves |

| Aortic valve involvement |

28 (52) |

7 (47) |

0.81 (0.25–2.57) |

0.723 |

| Mitral valve involvement |

38 (70) |

12 (80) |

2.74 (0.65–18.8) |

0.217 |

| Double valve |

12 (22) |

5 (33) |

1.75 (0.47–6.00) |

0.388 |

| Prosthetic valve endocarditis |

9 (17) |

4 (27) |

1.82 (0.43–6.79) |

0.385 |

| Echocardiographic parameters |

| LVDd (mm) |

52 [48–57] |

50 [43–62] |

0.98 (0.91–1.06) |

0.606 |

| LVDs (mm) |

34 [27–38] |

28 [23–49] |

1.02 (0.95–1.08) |

0.573 |

| EF (%) |

65 [57–74] |

73 [49–78] |

0.99 (0.95–1.04) |

0.746 |

| Systolic tricuspid pressure gradient (mmHg) |

40 [23–55] |

42 [27–60] |

1.00 (0.97–1.04) |

0.822 |

| Maximum length of vegetation (mm) |

15 [10–20] |

11 [9–21] |

0.99 (0.90–1.07) |

0.836 |

| Acute cerebral infarction |

15 (28) |

6 (40) |

1.73 (0.51–5.69) |

0.371 |

| Intracranial hemorrhagic lesion |

9 (17) |

3 (20) |

1.25 (0.25–4.97) |

0.766 |

| Laboratory valuables at diagnosis |

| White blood cell count (×104/μL) |

13.4 [9.6–19.3] |

12.8 [7.5–15.6] |

0.92 (0.81–1.01) |

0.085 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) |

9.0 [5.8–16.7] |

9.1 [4.1–18.9] |

1.00 (0.93–1.07) |

0.912 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.0 [8.5–12.4] |

7.9 [7.5–10.4] |

0.66 (0.43–0.93) |

0.033 |

| Platelet counts (×104/μL) |

117 [47–206] |

75 [36–105] |

0.89 (0.79–0.98) |

0.034 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) |

32 [17–59] |

29 [23–63] |

1.01 (0.98–1.03) |

0.530 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

1.21 [0.91–1.75] |

1.06 [0.75–2.29] |

1.11 (0.79–1.48) |

0.496 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

62 [35–95] |

71 [28–82] |

1.00 (0.99–1.02) |

0.739 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) |

0.9 [0.7–1.5] |

1.4 [0.8–2.2] |

1.11 (0.59–1.85) |

0.709 |

| Total protein (mg/dL) |

6.0 [5.3–6.6] |

5.4 [4.7–6.3] |

0.58 (0.28–1.14) |

0.125 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) |

2.6 [2.3–2.9] |

2.5 [2.1–2.7] |

0.80 (0.22–2.56) |

0.723 |

| Duration between diagnosis and surgery (days) |

2 [0–9] |

2 [1–11] |

1.01 (0.98–1.05) |

0.443 |

| Laboratory valuables just before surgery |

| White blood cell counts (×104/μL) |

14.4 [10.0–18.8] |

9.6 [6.5–15.4] |

0.88 (0.77–0.98) |

0.022 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) |

7.4 [4.5–11.9] |

8.7 [3.3–11.5] |

1.00 (0.91–1.09) |

0.976 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

9.5 [8.4–11.4] |

9.3 [8.1–11.0] |

0.89 (0.63–1.23) |

0.505 |

| Platelet counts (×104/μL) |

12.8 [7.0–18.1] |

6.1 [3.0–9.1] |

0.86 (0.74–0.96) |

0.018 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) |

37 [19–61] |

38 [26–47] |

0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

0.563 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) |

1.53 [0.86–2.08] |

1.31 [1.07–1.86] |

0.85 (0.45–1.22) |

0.501 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) |

42 [29–96] |

45 [42–77] |

1.00 (0.81–1.01) |

0.833 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) |

0.9 [0.6–1.4] |

2.0 [0.8–2.4] |

1.55 (1.05–2.55) |

0.038 |

| Aortic valve |

| Valve replacement |

28 (52) |

7 (46) |

0.82 (0.26–2.56) |

0.722 |

| Bioprosthetic valve |

23 (43) |

7 (46) |

– |

0.227 |

| Mechanical valve |

5 (9) |

0 (0) |

– |

0.227 |

| Aortic root surgery |

6 (11) |

2 (13) |

1.23 (0.22–6.83) |

0.812 |

| Annular patch repair |

8 (15) |

4 (27) |

2.09 (0.53–8.22) |

0.284 |

| Mitral valve |

| Valve repair |

6 (11) |

3 (20) |

1.6 (0.34–7.59) |

0.552 |

| Valve replacement |

32 (59) |

10 (19) |

1.38 (0.41–4.58) |

0.603 |

| Bioprosthetic valve |

24 (44) |

9 (60) |

1.31 (0.34–5.06) |

0.693 |

| Mechanical valve |

8 (15) |

1 (7) |

0.31 (0.04–2.78) |

0.275 |

| Annular patch repair |

7 (13) |

2 (13) |

1.01 (0.19–5.47) |

0.990 |

| Required CABG |

6 (11) |

0 (0) |

– |

0.177 |

| Required double valve surgery |

12 (22) |

5 (33) |

1.75 (0.50–6.11) |

0.377 |

| Required annular reconstruction |

16 (29) |

4 (27) |

1.04 (0.25–4.28) |

0.955 |

| Operative time and transfusion |

| Operative time (h) |

6.63 [4.82–8.77] |

5.83 [4.17–8.63] |

1.06 (0.89–1.26) |

0.473 |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass time (h) |

3.25 [2.55–4.78] |

3.25 [2.30–4.37] |

1.13 (0.84–1.51) |

0.397 |

| Aortic clamp time (h) |

2.42 [1.82–3.53] |

2.45 [1.40–3.65] |

1.14 (0.74–1.71) |

0.545 |

| Platelet transfusion (units) |

20 [2.5–40] |

33 [20–53] |

1.04 (1.00–1.09) |

0.050 |

Data are given as n (%) or median [interquartile range]. eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. Other abbreviations as in Tables 1–3.

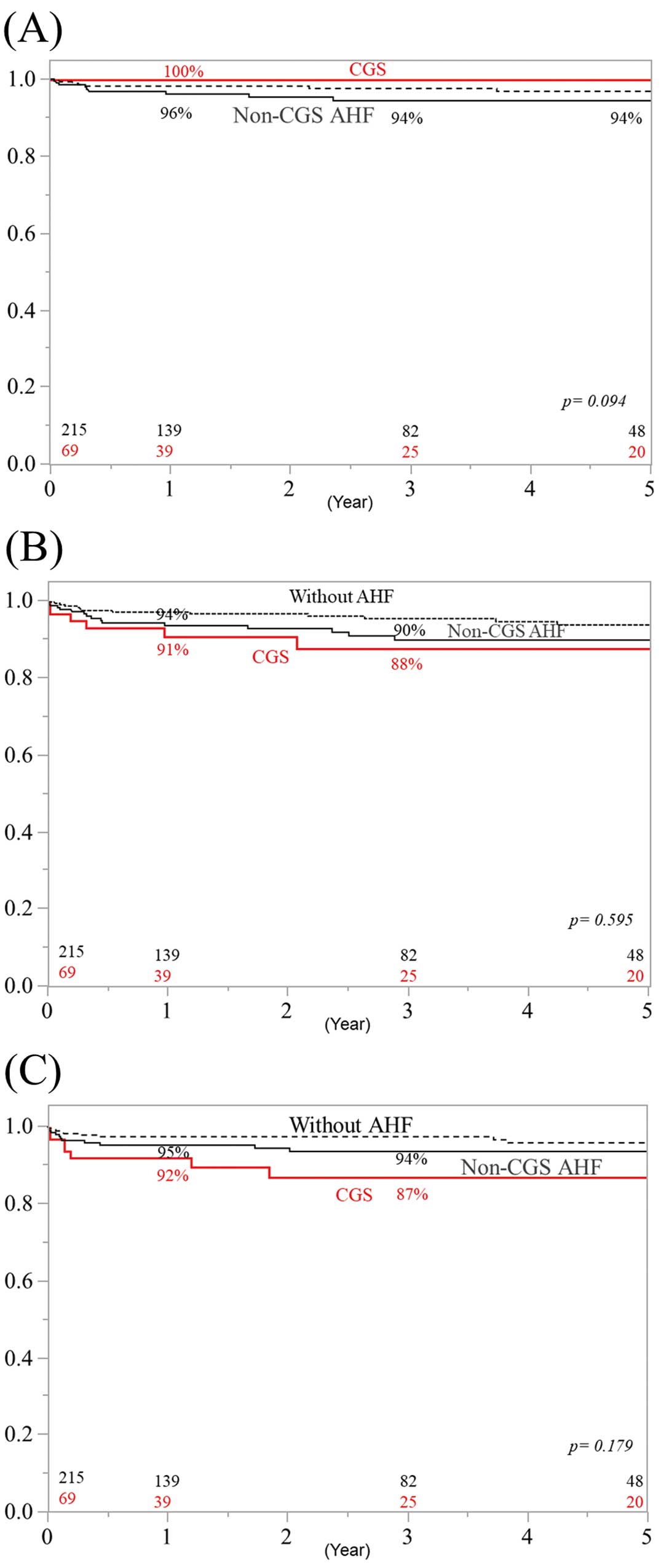

Overall survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years for the 69 CGS patients were 76%, 69%, and 69%, respectively (Figure 1). These rates did not differ significantly from those for non-CGS AHF patients (P=0.455). In addition, there were no significant differences between CGS and non-CGS AHF patients in cerebrovascular-related deaths (Figure 2A), cardiovascular-related deaths (Figure 2B), and infection-related deaths (Figure 2C). Freedom from IE recurrence rates at 1, 3, and 5 years in CGS patients were 97%, 87%, and 83%, respectively (Figure 3). These rates did not differ significantly from those for non-CGS AHF patients.

Discussion

The primary findings of the present study are that: (1)

S. aureus

infection, double valve involvement, and vegetation size were risk factors for CGS; (2) although there was a trend for higher in-hospital mortality rates in CGS patients, overall mid-term mortality was equivalent to that of non-CGS AHF patients; and (3) organ failure-related death was the leading cause of death after valve surgery in CGS patients.

AHF is one of the most prevalent complications of active IE. Previous studies reported that the prevalence of AHF in left-sided IE was 19–44%.1,11–14

Several factors, such as older age, diabetes, and aortic valve involvement, have been reported as risk factors for heart failure.1,14

Unfortunately, some patients with heart failure develop CGS, although the prevalence and risk factors for CGS have not been analyzed until now. The analysis of risk factors of CGS is important because it is critical to determine immediately whether heart failure is responsive to medical treatment or whether it is refractory and may deteriorate into CGS. In the present study,

S. aureus

infection, double valve involvement, and maximum vegetation length were risk factors for the development of CGS. It is important that the ejection fraction and systolic blood pressure were similar in CGS patients and both non-AHF and non-CGS AHF patients; however, heart rate was significantly greater in the CGS group. This is probably because heart failure in IE patients is due to the acute onset of valve destruction with severe valve regurgitation, and patients in CGS usually have a normal myocardium.

S. aureus

infection has been reported14

as a risk factor for worse outcome in IE patients, probably through large vegetation and invasion of another valve, which can cause complicated severe valve regurgitation and/or intracardiac abnormal fistula. In the present study double valve involvement was a risk factor for CGS, whereas aortic valve involvement has been reported as a risk factor for heart failure.14

Therefore, in patients with these factors, it is critically important not to wait for a response to medical therapy; instead, early valve surgery should be performed to avoid deterioration into CGS.

In the present study 38 (55%) CGS patients underwent valve surgery within 2 days of diagnosis. To date, the presence of heart failure has been reported as a risk factor after valve surgery,1,6

and in-hospital mortality after valve surgery in patients with heart failure is approximately 20%.1

Of these heart failure cases,1

although CGS has been indicated as a definitive indication for valve surgery,4

little is known about the clinical results after valve surgery. In the present study, there was a trend for higher postoperative in-hospital mortality for CGS patients compared with non-CGS AHF patients (22% vs. 13%, respectively; P=0.079). These mortality rates for CGS and non-CGS AHF patients are higher than their calculated EuroSCORE II values. Previous reports revealed that

S. aureus

infection, acute renal failure, septic shock, CGS, and thrombocytopenia are risk factors for worse outcomes in IE patients.15,16

However, the EuroSCORE II does not consider these factors precisely to calculate operative risk. This may be why the mortality rate for CGS and non-CGS AHF patients is higher than the EuroSCORE II. Conversely, the mortality rate of CGS and non-CGS AHF patients is similar to their calculated JapanSCORE. Furthermore, Gelsomino et al reported that the early mortality rate in CGS mitral valve IE patients was 19.5%,17

which is similar to the findings in the present study. In addition, Gelsomino et al reported that CGS was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality in mitral IE patients.17

Although there are some differences, the findings regarding mid-term overall survival rates in the present study are concordant with those of a previous report of mid-term results,17

namely that survival is similar for CGS and non-CGS AHF patients. This is probably because cardiac contraction was preserved even in the CGS patients, and if patients recover from a critical condition, their prognosis will be favorable. Therefore, prompt surgery should be performed in patients with CGS.

Of interest, the predictors of in-hospital mortality were different from the predictors of CGS. In the present study, organ failure, but not heart failure-related death, was the leading cause of in-hospital mortality. Nadji et al reported that multiple organ failure was the leading cause of death in heart failure patients but not CGS patients after valve surgery.14

The findings of the present study are partially concordant with the findings of Nadji et al because 10 of the 15 patients who died (66%) died of organ failure. In terms of renal function, Legrand et al reported that 59% of IE patients had acute kidney injury (AKI), whereas 9.9% of patients required renal replacement therapy.18

Although risk factors for AKI following cardiac surgery have been studied previously,19,20

patients with IE are likely to differ because of the ongoing inflammatory and infectious processes. The accumulation of injuries such as infection, systemic inflammation related to cardiopulmonary bypass, or the use of nephrotoxic antibiotics may further increase the risk of renal failure after surgery in IE patients. Regarding liver function, patients who died had a higher serum total bilirubin levels preoperatively, although there was no significant difference in total bilirubin levels at the time of IE diagnosis. This means that patients who died more likely had elevated serum total bilirubin levels at the time of IE diagnosis and valve surgery. Although a detailed strategy for CGS patients needs to be evaluated further, early surgery before the occurrence of organ function deterioration may improve clinical results.

Study Limitations

The present study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective multicenter study with relatively small numbers of patients in each hospital. Requirements for mechanical ventilation and/or mechanical circulatory support for CGS patients could differ between institutions and attending surgeons. Although the overall cohort included a sufficient number of patients, the number of patients with CGS was limited. Second, patients in whom surgical intervention was withheld due to poor status could not be evaluated, and the decision to proceed with surgical intervention or not was left up to each surgeon in each hospital. Therefore, a uniform definition of a “severe” condition may be lacking. Third, although all the CGS patients required mechanical ventilation for congestive heart failure and/or severe dyspnea, we could not completely distinguish CGS from septic shock because CGS and septic shock sometimes coexist. Finally, the positive blood culture rate was relatively low in the present study (around 75%). This may be due to the fact that this study was a multicenter analysis and the timing of blood cultures depends on each center.

Conclusions

In conclusion, clinical results after valve surgery in CGS patients remain severe; however, the mid-term results for CGS patients in the present study were equivalent to those for non-CGS AHF patients. Because end organ function was important for overall survival, early surgical intervention should be performed before end organ function deteriorates.

Sources of Funding

This study did not receive any specific funding.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0583

References

- 1.

Kiefer T, Park L, Tribouilloy C, Cortes C, Casillo R, Chu V, et al. Association between valvular surgery and mortality among patients with infective endocarditis complicated by heart failure. JAMA 2011; 306: 2239–2247.

- 2.

Park LP, Chu VH, Peterson G, Skoutelis A, Lejko-Zupa T, Bouza E, et al. Validated risk score for predicting 6-month mortality in infective endocarditis. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e003016.

- 3.

Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler VG Jr, Tleyjeh IM, Rybak MJ, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: Diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015; 132: 1435–1486.

- 4.

Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36: 3075–3128.

- 5.

Pettersson GB, Coselli JS, Hussain ST, Griffin B, Blackstone EH, Gordon SM, et al. 2016 The American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) consensus guidelines: Surgical treatment of infective endocarditis: Executive summary. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017; 153: 1241–1258.e29.

- 6.

Gaca JG, Sheng S, Daneshmand MA, O’Brien S, Rankin JS, Brennan JM, et al. Outcomes for endocarditis surgery in North America: A simplified risk scoring system. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 141: 98–106.e1–e2.

- 7.

Yoshioka D, Toda K, Yokoyama JY, Matsuura R, Miyagawa S, Kainuma S, et al. Diabetes mellitus adversely affects mortality and recurrence after valve surgery for infective endocarditis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018; 155: 1021–1029.e5.

- 8.

Li JS, Sexton DJ, Mick N, Nettles R, Fowler VG Jr, Ryan T, et al. Proposed modifications to the Duke criteria for the diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 30: 633–638.

- 9.

Yoshioka D, Toda K, Yokoyama JY, Matsuura R, Miyagawa S, Shirakawa Y, et al. Recent surgical results for active endocarditis complicated with perivalvular abscess. Circ J 2017; 81: 1721–1729.

- 10.

Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini FM, Focardi M, Lunghetti S, Bernazzali S, et al. Speckle tracking echocardiography as a new technique to evaluate right ventricular function in patients with left ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 32: 424–430.

- 11.

Hasbun R, Vikram HR, Barakat LA, Buenconsejo J, Quagliarello VJ. Complicated left-sided native valve endocarditis in adults: Risk classification for mortality. JAMA 2003; 289: 1933–1940.

- 12.

Chu VH, Cabell CH, Benjamin DK Jr, Kuniholm EF, Fowler VG Jr, Engemann J, et al. Early predictors of in-hospital death in infective endocarditis. Circulation 2004; 109: 1745–1749.

- 13.

Aksoy O, Sexton DJ, Wang A, Pappas PA, Kourany W, Chu V, et al. Early surgery in patients with infective endocarditis: A propensity score analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 364–372.

- 14.

Nadji G, Rusinaru D, Remadi JP, Jeu A, Sorel C, Tribouilloy C. Heart failure in left-sided native valve infective endocarditis: Characteristics, prognosis, and results of surgical treatment. Eur J Heart Fail 2009; 11: 668–675.

- 15.

Cameli M, Lisi M, Righini FM, Focardi M, Lunghetti S, Bernazzali S, et al. Speckle tracking echocardiography as a new technique to evaluate right ventricular function in patients with left ventricular assist device therapy. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013; 32: 424–430.

- 16.

Olmos C, Vilacosta I, Habib G, Maroto L, Fernández C, López J, et al. Risk score for cardiac surgery in active left-sided infective endocarditis. Heart 2017; 103: 1435–1442.

- 17.

Gelsomino S, Maessen JG, van der Veen F, Livi U, Renzulli A, Luca F, et al. Emergency surgery for native mitral valve endocarditis: The impact of septic and cardiogenic shock. Ann Thorac Surg 2012; 93: 1469–1476.

- 18.

Legrand M, Pirracchio R, Rosa A, Petersen ML, Van der Laan M, Fabiani JN, et al. Incidence, risk factors and prediction of post-operative acute kidney injury following cardiac surgery for active infective endocarditis: An observational study. Crit Care 2013; 17: R220.

- 19.

Palomba H, de Castro I, Neto AL, Lage S, Yu L. Acute kidney injury prediction following elective cardiac surgery: AKICS score. Kidney Int 2007; 72: 624–631.

- 20.

Dasta JF, Kane-Gill SL, Durtschi AJ, Pathak DS, Kellum JA. Costs and outcomes of acute kidney injury (AKI) following cardiac surgery. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 1970–1974.