論文ID: CJ-16-0856

論文ID: CJ-16-0856

Background: The impact of endovascular revascularization of the lower extremity arteries with atherectomy (AT) compared with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) is still unclear. Therefore, the aim of the study was to compare long-term outcomes after percutaneous PTA and AT in patients requiring endovascular revascularization.

Methods and Results: This was a single-center, retrospective registry of obstructive and symptomatic PAD patients who underwent endovascular revascularization. PTA was performed in 215 patients, and AT in 204 (Silver Hawk, EV3, n=125; CSI 360°, n=66; Pathway Medical Technologies, n=13). There were no significant between-group differences in baseline characteristics except for increased CAD, dialysis and CLI prevalence in the PTA group. Following propensity score analysis 131 well-matched pairs were included in analysis. Bail-out stenting was more frequent in the reference group (PTA, 6.1% vs. AT, 0%; P=0.004). At 6- and 12-month follow-up there were no differences in TLR between the groups (PTA, 8.3% vs. AT, 5.3%; P=0.47; and PTA, 16.7% vs. AT, 13.7%; P=0.73, respectively). The difference was in favor of AT at 24-month follow-up (PTA, 29.0% vs. AT, 16.7%; P=0.05). No difference was observed in amputation rate (PTA, 0.7% vs AT, 1.5%; P=0.62). On Kaplan-Meier analysis there were no significant differences between groups in time to TLR, amputation or death.

Conclusions: AT was associated with lower risk of TLR, and this should be confirmed in randomized controlled trials.

According to recent clinical practice and evidence, endovascular revascularization of the lower limb arteries has superseded surgical procedures.1,2 Regardless of advancement in endovascular technology, restenosis and the need for repeat revascularization are still challenging. Moreover, the mortality in peripheral artery disease (PAD), especially in critical limb ischemia (CLI), is high, fluctuating at around 20% at 6-month follow-up, and exceeding 50% within 5 years from diagnosis.3,4 These numbers increase in patients with coexisting symptomatic coronary artery disease (CAD). Additionally, CLI is associated with poor quality of life5 and high treatment costs.6 Nowadays, multiple therapies for PAD have emerged, including pharmacological regimens, endovascular and open surgery, drug-coated balloons (DCB), and stem cell therapy.7 On top of that, stenting has become popular, due to the reassuring early outcome. In contrast, in the femoropopliteal artery mechanical stress is high, thus implanted stents are exposed to the risk of stent fracture and malformation, increasing the rate of restenosis.8,9 In the below-the-knee (BTK) region, use of metal, balloon-expandable drug-eluting stents is more common than the self-expandable nitinol ones, because those stents are even more susceptible to fracture. Moreover, due to the characteristics of BTK lesions, in most cases multiple stents are needed.10 Therefore, atherectomy (AT), which removes the atherosclerotic plaque from the arterial wall, appears to be promising. This expectancy is linked to the fact that these devices cut out the plaque from the artery wall, thus significantly increasing lumen diameter and removing potential sources of inflammation, thus facilitating satisfactory outcome.11

Thus far, the long-term outcomes after endovascular revascularization of lower extremity arteries using AT compared with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) have been unclear, therefore the aim of this study was to compare the results of endovascular revascularization using AT with those for PTA.

This study is based on a retrospective registry of 425 consecutive patients with symptomatic PAD who underwent endovascular revascularization with AT or PTA between 2008 and 2012 at San Antonio Endovascular and Heart Institute. Two hundred and four patients were treated with AT and 215 underwent PTA.

Adult patients (>18 years old) with both intermittent claudication (Rutherford 3) and CLI (Rutherford 4–6) were included if they had at least 1 lesion with >70% diameter stenosis confirmed on live quantitative vessel angiography in a lower extremity artery. Patients with in-stent restenosis were excluded.

Procedural Characteristics and Pharmacological RegimenPercutaneous intervention was performed using standard techniques with a femoral ante- and retrograde approach. All patients received dual antiplatelet therapy with 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg or 600 mg clopidogrel before intervention unless they had previously received these medications. Bivalirudin or heparin (50–90 UI/kg) was used as the anticoagulant during the procedure. PTA was performed with plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) balloon diameters 80–90% of vessel reference diameter with low pressure and an inflation time of 60s. If required additional inflations were performed. Directional (Silver HawkTM, EV3), orbital (Diamondback 360°, CSI 360°) and directional with suction (JetstreamTM, Pathway, Bayer) AT devices were utilized in this study. Type of AT was left to the operator’s discretion, nonetheless directional AT was performed in soft and mixed plaques; orbital AT was utilized when the lesion appeared to be calcified; and directional with suction AT was performed when thrombus was suspected. Orbital AT was always followed by low-pressure balloon post-dilatation; and after directional AT, PTA was performed if residual stenosis was >30%. Distal protection system was not used for any patients. Angiographic success was defined as post-procedural TIMI 3 flow, no dissection and residual stenosis <30%. If angiographic success was not achieved bail-out stenting was performed. Aspirin (81 mg/day) was continued indefinitely whereas clopidogrel (75 mg/day) was advised to be continued for 12 months after the procedure, and atorvastatin, at the maximum tolerable dose, usually 40 mg daily.

AT DevicesA description of AT devices currently available is given by Akkus et al.12 The Silver Hawk plaque excision system (ev3, Plymouth, MN, USA) is a forward cutting directional AT device. The device consists of a rotating blade inside a tubular housing with a collection space in the nose cone. The device is enable to perform AT in vessels with a diameter of 1.5–7 mm.

Diamondback 360° (CSI360°) is an orbital AT system tipped with an eccentric, diamond-coated crown. The crown rotation speed can vary from 60,000 to 200,000 rpm. The crown may be advanced forward and backward when it is intra-arterial. The needed diameter is achieved by increasing speed rotation. Faster speeds result in increased centrifugal force, yielding a larger orbit, and this device is recommended for calcified lesions. Usually, orbital AT is performed before stenting/balloon angioplasty.

The Pathway Jetstream PV Atherectomy System (Pathway Medical Technologies, Redmond, WA, USA) is a rotational AT device with a front-cutting tip that spins at 60–70,000 rpm. Jetstream® expandable catheters have a catheter tip that remains at a diameter of 2.1–2.4 mm when rotating clockwise and 2.4–3.4 mm when rotating counterclockwise. For BTK interventions this device is available in a fixed size: 1.6 mm and 1.85 mm. This is the only AT device on the market with active aspiration. The derbies as well as thrombus are collected in the bag located on the console device, outside the body.

Study Endpoints and DefinitionsBecause of the observational nature of this study, no preliminary hypothesis was generated. Target lesion revascularization (TLR) was considered a primary endpoint and was defined as any symptom-driven revascularization within a previously treated segment. Unplanned amputation related to a previously treated vessel and bail-out stenting were regarded as secondary endpoints. Moreover, incidents of vessel perforation, dissection and distal embolization were collected.

Safety and EthicsThis retrospective study was conducted in accordance with standard ethics guidelines. Endovascular procedures were carried out by experienced interventional cardiovascular teams in a high-volume center with vascular surgery back up within 30 min of transportation.

Data Collection and Follow-upClinical and procedural data were collected on case report forms generated by the hospital electronic system, containing all patient hospitalization and discharge information. This system is audited for institutional quality assurance by private insurance companies and the state health fund.

The long-term follow-up data were collected during ambulatory check-up or by telephone. It was usually scheduled each 3–5 months. All outcomes of interest were confirmed using hospital discharge files. Three patients met exclusion criteria for in-stent restenosis and 3 were lost to follow-up.

Statistical AnalysisContinuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median (IQR). Data were compared using the t-test for parametric or Mann-Whitney U-test for non-parametric continuous variables. Categorical variables are reported as frequencies (percentages) and were compared using the chi-squared or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Survival curves were constructed using Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared using the log-rank test. Because of the non-randomized nature of the study, propensity score analysis was utilized to adjust for differences in patient baseline characteristics. The logistic regression model predicting PTA and AT assignment contained all covariate data categories. The resulting propensity scores were matched using the nearest available Mahalanobis metric matching within calipers (0.25×propensity score mean). The resulting standardized difference was calculated for all baseline covariates. All reported P-values are 2-tailed, and P<0.05 was considered significant. GraphPad 6 Prism was used for statistical analysis.

Patient baseline demographic and angiographic characteristics before propensity score matching are listed in Table 1A,1B, respectively. The prevalence of CAD, end-stage renal disease and CLI was more common in the PTA cohort. Therefore, the propensity score was adjusted.

| A | PTA | AT | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 215 | 204 | |

| Male | 134 (62.3) | 123 (60.2) | 0.688 |

| Age (years) | 69±11.8 | 70±12.1 | 0.675 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.6±5.4 | 28.6±4.9 | 0.91 |

| Smokers | 35 (16.2) | 34 (16.6) | 0.99 |

| Hypertension | 212 (98.6) | 203 (99.5) | 0.624 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 212 (98.6) | 197 (96.5) | 0.132 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 159 (73.9) | 132 (64.7) | 0.07 |

| CAD | 188 (87.4) | 163 (79.9) | 0.046 |

| CABG | 81 (37.6) | 55 (26.9) | 0.022 |

| PCI | 109 (50.6) | 108 (52.9) | 0.78 |

| Dialysis reliant | 74 (34.4) | 44 (21.5) | 0.046 |

| CLI | 56 (26.0) | 35 (17.1) | 0.032 |

| Rutherford symptoms | 3 (3–6) | 3 (3–6) | 1.00 |

| B | PTA | AT | P-value |

| Iliac | 8 (2.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0.85 |

| Common femoral artery | 7 (1.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0.78 |

| SFA | 71 (19.9) | 79 (25.2) | 0.06 |

| Profunda femoral artery | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 0.95 |

| Popliteal artery | 28 (7.8) | 32 (10) | 0.61 |

| Anterior tibial artery | 82 (22.9) | 80 (25.5) | 0.47 |

| Trunk | 57 (15.9) | 18 (5.7) | 0.65 |

| Posterior tibial artery | 57 (15.9) | 47 (15.0) | 0.08 |

| Peroneal artery | 41 (11.4) | 28 (8.9) | 0.85 |

| Dorsalis pedis artery | 12 (3.3) | 8 (2.5) | 0.41 |

| Calcaneal artery | 21 (5.8) | 8 (2.5) | 0.32 |

| Plantar artery | 5 (1.4) | 0 | NS |

| ATK | 119 (33.3) | 124 (39.7) | 0.11 |

| BTK | 238 (66.6) | 189 (60.3) | 0.46 |

| Bypass | 4 (1.1) | 9 (2.8) | 0.05 |

| CTO | 58 (16.2) | 76 (24.2) | 0.01 |

| TASC A femoropopliteal | 43 (36.1) | 40 (32.2) | 0.58 |

| TASC B femoropopliteal | 35 (29.4) | 43 (34.6) | 0.41 |

| TASC C femoropopliteal | 25 (21.4) | 28 (22.5) | 0.87 |

| TASC D femoropopliteal | 16 (13.4) | 13 (10.4) | 0.55 |

(A) Data given as mean±SD, n (%) or median (IQR). (B) Data given as n (%). AT, atherectomy; ATK, above the knee; BMI, body mass index; BTK, below the knee; CABG, coronary aortic bypass graft; CAD, coronary artery disease; CLI, critical limb ischemia; CTO, chronic total occlusion; PCI, percutaneous intervention; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; SFA, superficial femoral artery; TASC, the Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus Document on Management of Peripheral Arterial Disease.

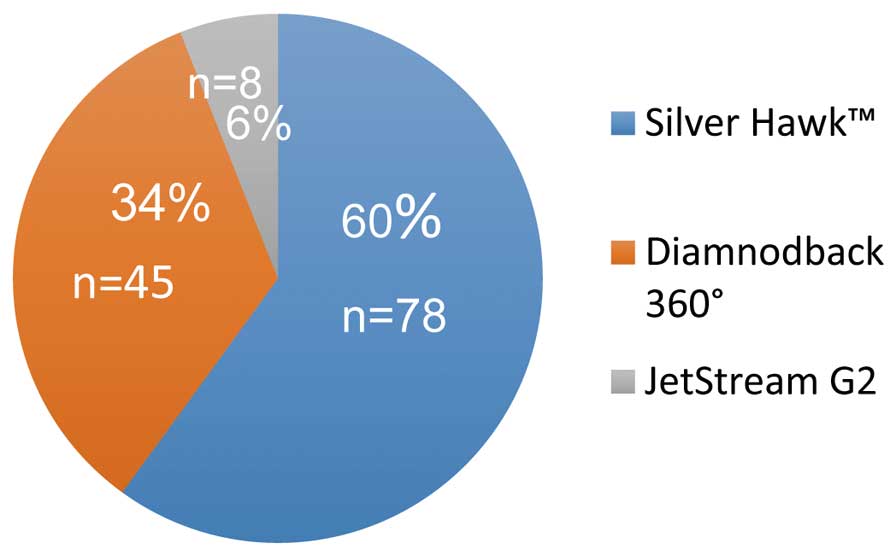

Following propensity score analysis and matching, 131 pairs were selected. There were no differences in demographic or procedural characteristics between cohorts after adjustment (Tables 2,3, respectively). The proportion of AT usage is shown in Figure 1. Results of unadjusted analysis are presented in Figure S1. In the peri-procedural period there were no differences in the occurrence of adverse events, but ail-out stenting due to flow-limiting dissection was required more often in the PTA group (PTA, 6.1% vs. AT, 0.0%, P=0.001; Table 4). At follow-up there were no differences between the groups in TLR at 6-month (PTA, 8.3% vs. AT, 5.3%, P=0.47) or 12-month follow-up (PTA, 16.7% vs. AT, 13.7%, P=0.73). At 24-month follow-up TLR was more frequent in the reference group (PTA, 29.0% vs. AT, 16.7%, P=0.05; Figures 2,S2). The amputation rate was similar between groups (PTA, 0.7% vs. AT, 1.5%, P=0.62; Figures 3,S3). On Kaplan-Meier analysis there were no differences in TLR-free survival, amputation-free survival, or survival rate (OR, 1.13; 95% CI: 0.68–1.87, P=0.63; OR, 0.23; 95% CI: 0.01–0.45, P=0.19; and OR, 2.09; 95% CI: 0.62–7.06, P=0.23, respectively; Figures 4,S4).

| PTA | AT | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 131 | 131 | |

| Male | 85 (64.8) | 81 (61.8) | 0.70 |

| Age (years) | 69±12.36 | 69.2±12.0 | 0.87 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.8±5.7 | 28.6±4.6 | 0.89 |

| Smokers | 15 (11.4) | 15 (11.4) | 1.0 |

| Hypertension | 131 (100) | 131 (100) | 1.0 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 129 (98.4) | 129 (98.4) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 99 (75.5) | 105 (82.4) | 0.46 |

| CAD | 111 (84.7) | 112 (85.4) | 1.0 |

| CABG | 46 (35.1) | 48 (36.6) | 0.89 |

| PCI | 78 (59.5) | 73 (55.7) | 0.61 |

| Dialysis reliant | 38 (29.0) | 39 (29.7) | 1.0 |

| CLI | 25 (19.0) | 27 (20.6) | 0.87 |

| Rutherford symptoms | 3 (3–6) | 3 (3–6) | 0.65 |

Data given as mean±SD, n (%) or median (IQR). Abbreviations as in Table 1.

| PTA | AT | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iliac artery | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Common femoral artery | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 1.0 |

| SFA | 49 (23.0) | 48 (22.5) | 1.0 |

| Profunda femoral artery | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1.0 |

| Popliteal artery | 18 (8.4) | 19 (8.9) | 1.0 |

| Anterior tibial artery | 52 (24.4) | 54 (25.3) | 0.91 |

| Trunk | 10 (4.6) | 13 (6.1) | 0.66 |

| Posterior tibial artery | 33 (15.4) | 34 (15.9) | 1.0 |

| Peroneal artery | 22 (10.3) | 23 (10.7) | 1.0 |

| Dorsalis pedis artery | 6 (2.8) | 6 (2.8) | 1.0 |

| Calcaneal artery | 12 (5.6) | 6 (2.8) | 0.22 |

| Plantar artery | 4 (1.8) | 0 | 0.12 |

| All | 213 | 213 | |

| ATK | 70 (32.8) | 70 (32.8) | 1.0 |

| BTK | 143 (67.2) | 143 (67.2) | 1.0 |

| Bypass | 4 (1.8) | 7 (3.2) | 0.54 |

| CTO | 29 (13.6) | 32 (15.0) | 0.78 |

| TASC A femoropopliteal | 23 (32.8) | 21 (30.0) | 0.85 |

| TASC B femoropopliteal | 20 (28.5) | 23 (32.8) | 0.71 |

| TASC C femoropopliteal | 17 (24.2) | 19 (27.1) | 0.84 |

| TASC D femoropopliteal | 10 (14.2) | 7 (10.0) | 0.60 |

Data given as n (%). Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Distribution of atherectomy device type after propensity score matching.

| PTA | AT | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Artery perforation | 1 (0.7) | 1 (0.7) | 1.0 |

| Distal embolization | 0 | 1 (0.7) | 1.0 |

| Flow-limiting dissection | 8 (6.1) | 0 | <0.001 |

| Bail-out stenting | 8 (6.1) | 0 | <0.001 |

Data given as n (%). Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Target lesion revascularization at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years after propensity score matching. AT, atherectomy; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

Amputation at 2-year follow-up and bail-out stenting after propensity score matching. AT, atherectomy; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of (A) target lesion revascularization (TLR)-free survival; (B) amputation-free survival; and (C) overall survival after propensity score matching. AT, atherectomy; PTA, percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

The current study reports a direct observational comparison of PTA with different types of AT devices. To the best of our knowledge, the present study describes, for the first time, direct comparison of the long-term outcomes of PTA vs. AT in a large cohort. In this propensity score-matched registry, despite some discrepancies in patient baseline characteristics in favor of the AT group, the PTA group had lower requirement for procedural bail-out stenting. At long-term follow-up, there were no differences in amputation rate, but the AT group had a significantly smaller rate of TLR at 24-month follow-up. After adjustment, there were no differences between groups at baseline or in procedural characteristics, and the results were sustained. It must be noted that this registry includes a relatively large number of patients with diabetes, end-stage renal disease, CLI and chronic total occlusions, thus representing a high-risk cohort for adverse events. These comorbidities may have a strong effect on prognosis, especially with regard to cardiovascular complications, and accelerate the process of restenosis. Despite this, the complication rate was low in both groups, nevertheless more frequent stenting due to flow-limiting dissection was necessary in the PTA group.

In the TALON registry, in which Silver Hawk was used exclusively for above-the-knee (ATK) as well as BTK lesions, at 6-month and at 1-year follow-up the TLR rate was 10% and 20%, respectively.13 Similar results were noted in the DEFINITIVE LE prospective registry 1-year follow-up, in which 800 patients with claudication as well as with CLI were included.14 The rate of TLR was 17% and 22% for the superficial artery and BTK, respectively. Limb salvage rate was 95%. Moreover, Zeller et al described the mid-term results after BTK revascularization with Silver Hawk. At 6-month follow-up, 94.1% of patients were free from TLR.15 Another study with Silver Hawk published by McKinsey et al in which patients with ATK and BTK lesions were enrolled, noted rates of TLR between 25.3% (claudicants) and 30.1% (CLI).16 The safety and efficiency of orbital AT were proven in 2 prospective registries and in 1 randomized trial. In the CONFIRM registry the safety and high rate of acute angiographic outcomes were proven.17 In the OASIS trial orbital AT had satisfactory results in infrapopliteal lesions, nevertheless adjunctive balloon angioplasty was performed after plaque modification only in 42.6%.18 In the CALCIUM 360 trial, the infra-popliteal arteries in 50 patients with CLI were qualified to plaque modification with subsequent balloon angioplasty vs. balloon angioplasty alone.19 In that study the AT group had a lower rate of target vessel revascularization and all-cause mortality in comparison with balloon angioplasty alone. Moreover, procedure success was achieved more frequently in the AT group than for balloon angioplasty alone. The results of that study are also similar to the present mid-term results. The rarely utilized AT device used in the present registry was the Pathway Jetstream. Zeller et al carried out revascularization using the Pathway Jetstream AT system in 210 lesions.20 AT 6-month and 12-month follow-up, TLR was required in 15% and 26% of patients, respectively. Another study compared 1-year outcomes after revascularization with the Pathway Jetstream in diabetic vs. non-diabetic patients, in whom 20% and 28% had target lesion failure, respectively.21 In the TRUE study, the TLR rate was 11%, nevertheless the aim of the study was to assess the effectiveness of plaque removal with the Pathway Jetstream, confirmed on intravascular imaging.22 Only 18 patients were enrolled. A recent study noted the successful outcome after revascularization of severe calcified superficial femoral artery with the Pathway Jetstream, assessed on intravascular ultrasound.23 Following this, Todd et al described endovascular revascularization of CLI of the tibial artery with 3 types of AT: laser, orbital, and directional, compared with PTA alone.24 They concluded that there were no differences between the groups, with patency in the AT and PTA groups at 24 month follow-up of 51% and 62%, respectively.

In comparison with the Silver Hawk studies, the present study noted similar results, nevertheless in the TALON study as well as in the DEFINITIVE LE, the rate of CLI, diabetes and dialysis reliance was lower. Moreover, severe calcified lesions were excluded. A higher rate of TLR was observed in the registries mentioned above, in contrast to trials in which orbital AT was evaluated. Nevertheless, orbital AT was used exclusively regardless of whether the lesions were calcified, and adjunctive PTA was not always performed. In trials in which Pathway was utilized, the results were poorer than in the present study. This AT device, however, was associated with the lowest number of enrolled patients, in comparison with Silver Hawk and orbital AT. On direct comparison of revascularization of the tibial artery with 3 types of AT to PTA in patients with CLI, there were no differences between the groups. Moreover, the outcomes were less promising than in the present study, although the CLI patients comprised the minority of the present subjects.

An interesting technology that may be combined with AT as an adjunct therapy is DCB after plaque modification. So far the outcomes of DCB in the femoropopliteal region are promising,25,26 but in the BTK region the results are still suboptimal.27,28 Nevertheless, early reports on the combination of plaque modification with AT and subsequent DCB look promising.29,30 Novel technologies, including local drug delivery nano-technology, may soon be able to be utilized after plaque modification by AT.31

All patients in this registry were also treated pharmacologically in order to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular adverse events. Despite encouraging data on the addition of cilostazol to treatment after stenting of the femoropopliteal region,32 almost all of the present patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) consisting of clopidogrel (75 mg) and acetylsalicylic acid (81 mg) once per day. DAPT was prescribed due to the fact that after AT the intima-media could be exposed to blood flow, significantly increasing the risk of acute or subacute thrombosis.33

To summarize, the preferential outcome of AT in the long term, when compared with POBA alone in the present study, is multifactorial. As shown in previously cited studies as well as the present study, plaque modification and removal with AT provide a more predictable and stable outcome, as reflected by the by lower rate of bail-out stenting. Additionally, vessel injury after AT might be lower compared with overstretch with POBA, resulting in improved vascular response and lower neointimal hyperplasia, therefore translating into lower TLR at follow-up.

Study LimitationsThe retrospective nature of this study was the major limitation, along with the differences in baseline patient characteristics. Nevertheless, after propensity score matching the differences were eliminated. The exact data on very long BTK CTO are unavailable. This study is hypothesis generating only.

In this hypothesis-generating registry of patients with lower extremity PAD, AT was associated with lower long-term risk of procedural bail-out stenting and lower rate of repeated TLR compared with POBA. Nevertheless, this should be confirmed in randomized controlled trials.

None.

Supplementary File 1

Figure S1. Distribution of atherectomy device type before propensity score matching.

Figure S2. Target lesion revascularization at 6 months, 1 year and 2 years before propensity score matching.

Figure S3. Amputation at 2-year follow-up and bail-out stenting before propensity score matching.

Figure S4. Kaplan-Meier analysis of (A) target lesion revascularization (TLR)-free survival; (B) amputation-free survival; and (C) overall survival before propensity score matching.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-16-0856