Abstract

Background:

The purpose of this study was to clarify the current status and issues of community collaboration in heart failure (HF) using a nationwide questionnaire survey.

Methods and Results:

We conducted a survey among hospital cardiologists and general practitioners (GPs) using a web-based questionnaire developed with the Delphi method, to assess the quality of community collaboration in HF. We received responses from 46 of the 47 prefectures in Japan, including from 281 hospital cardiologists and 145 GPs. The survey included the following characteristics and issues regarding community collaboration. (1) Hospital cardiologists prioritized medical intervention for preventing HF hospitalization and death whereas GPs prioritized supporting the daily living of patients and their families. (2) Hospital cardiologists have not provided information that meets the needs of GPs, and few regions have a community-based system that allows for the sharing of information about patients with HF. (3) In the transition to home care, there are few opportunities for direct communication between hospitals and community staff, and consultation systems are not well developed.

Conclusions:

The current study clarified the real-world status and issues of community collaboration for HF in Japan, especially the differences in priorities for HF management between hospital cardiologists and GPs. Our data will contribute to the future direction and promotion of community collaboration in HF management.

In Japan’s super-aging society, the number of patients with heart failure (HF) increases by 10,000 per year and has come to be considered an “HF pandemic”.1,2

The population of frail elderly patients with HF is also increasing. A recent HF registry study revealed that the average age of Japanese patients with HF is 80 years old, 21% lived alone and 42% lived with a partner, suggesting that many older people are each other’s caregiver.3

Additionally, 48% of patients were judged to require support or care under the long-term care insurance.3

Thus, multidisciplinary support and care of elderly patients with HF are urgent and critical issues in Japan.

To provide appropriate care and to support the lives of elderly patients with HF, it is essential to establish a collaborative system of medical and nursing care in the community.4

In particular, collaboration between hospital cardiologists and general practitioners (GPs) in the community is important.

In Japan, the Basic Act on Measures to Cope with Cardiovascular Diseases was enacted in 2019, which calls for the establishment of community collaboration for HF and specific measures and systems. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the current status of community collaboration in HF and to standardize it. However, the actual status of community collaboration for HF in Japan is unclear. Thus, the purpose of this study was to clarify the current status and problems in community collaboration for HF using a questionnaire survey, to provide helpful information to establish a community collaboration system for patients with HF in Japan.

Methods

We administered a nationwide questionnaire survey among hospital cardiologists and GPs. The web-based questionnaire was conducted from December 2–25, 2020 (https://plaza.umin.ac.jp/isobegroup/). We also requested members of the Japan Heart Failure Society, Japan Primary Care Association, Japan Association of Home Health Care, and Japan Medical Association (Itabashi-ku, Tokyo) to complete the questionnaire via e-mail. The definition of cardiologist was based on the respondent’s assessment, and GPs were defined as general practitioners who work in clinics.

The questionnaire was developed using the following steps and the Delphi method, as previously described.5

(1) A working group within the research team developed quality indicators for HF care based on existing HF guidelines, statements, and quality indicators in various countries.4,6–23

(2) A group of 64 experts in various fields from the research team (hospital physicians, GPs, dentists, nurses, pharmacists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, dietitians, and care support specialists, among others) conducted 2 evaluation rounds of the web-based questionnaire and rated the appropriateness of each indicator on a scale of 1–9, as follows: 1 (very inappropriate), 5 (undecided), and 9 (very appropriate). Appropriateness was defined as the quality of HF care that is standard and desirable to achieve in all regions. After the first questionnaire was completed, the working group discussed and revised the indicators based on the comments from raters and added new indicators suggested by the raters. After providing feedback on the scoring results and sharing comments among the raters, the second evaluation was conducted. We defined an indicator as appropriate if >80% of raters scored it between 7 and 9.5

(3) A 2-pattern questionnaire was developed (Supplementary Tables 1,2) to query hospital physicians and GPs regarding achievement of quality in their usual HF care based on the developed quality indicators. Each questionnaire had 5 domains: (1) goals of community collaboration in HF; (2) quality of community collaboration in HF; (3) quality of community information sharing in HF; (4) quality of medical care in HF; and (5) quality of multidisciplinary care in HF.

The quality of care was subjectively rated “Yes” or “No” or by a 5-point scale, depending on the question. The 5-point scale was as follows: 1 (not done), 2 (not done in most patients), 3 (done in approximately 50% of patients), 4 (done in most patients), 5 (done in all patients). We assessed quality of care by comparing the percentage of respondents who answered “Yes” or the percentage of respondents who answered “4–5 points”. Quality of care in which ≥80% of respondents selected “Yes” or “4–5 points” for achievement was defined as high quality, 50–79% was defined as moderate quality, and <50% was defined as low quality. Differences in the achievement of care quality for each question were compared among the following 3 groups: (1) hospital cardiologists, (2) GPs who were cardiologists, and (3) GPs who were not cardiologists.

Ethical Considerations

All respondents provided informed consent for study participation. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sakakibara Heart Institute (No. 20-047) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors take complete responsibility for the integrity of questionnaire creation, data collection, the study design, and accuracy of the data analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median and interquartile range, and categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Comparisons of categorical variables among the 3 groups were analyzed using the chi-squared test, and differences between pairs were assessed using the Bonferroni test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R version 2.13.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

The background information of the survey respondents is shown in

Tables 1,2. We received responses from 46 of the 47 prefectures in Japan, including from 281 hospital cardiologists and 145 GPs. Among hospital cardiologists, 89% of respondents were men, with the largest proportion aged 40–49 years (34%), followed by those aged 50–59 years (32%). The most common cardiology specialization was HF (65%), followed by ischemic heart disease (43%). Among GPs, 91% of respondents were men, with the largest proportion aged 50–59 years (39%), followed by those aged 40–49 years (31%). The most common department in the clinics was internal medicine (84%), followed by cardiovascular medicine (57%) and pediatrics (17%).

Table 1.

Background of Hospital Cardiologist Questionnaire Respondents

| Age, n (%) |

20–29 years: 2 (0.7)

30–39 years: 44 (15.7)

40–49 years: 96 (34.2)

50–59 years: 90 (32.0)

60–69 years: 43 (15.3)

≥70 years: 6 (2.1) |

| Male sex, n (%) |

250 (89.0) |

| Expertise, n (%) |

Ischemic heart disease: 121 (43.1)

Heart failure: 183 (65.1)

Arrhythmia: 35 (12.5)

Hypertension: 40 (14.2)

Echocardiography: 40 (14.2)

Cardiac rehabilitation: 63 (22.4)

Intensive care: 11 (3.9) |

| Region, n (%) |

Hokkaido region: 15 (5.0)

Tohoku region: 22 (8.0)

Kanto region: 78 (28)

Chubu region: 44 (16)

Kinki region: 49 (17)

Chugoku region: 17 (6)

Shikoku region: 14 (5)

Kyushu-Okinawa region: 42 (15) |

| No. of beds, n (%) |

<100 beds: 18 (6.4)

100–499 beds: 144 (51.2)

500–799 beds: 75 (26.7)

≥800 beds: 44 (15.7) |

No. of full-time cardiologists,

n (%) |

1–5: 112 (39.9)

6–10: 62 (22.1)

11–20: 51 (18.1)

≥21: 56 (19.9) |

Annual no. of patients admitted

with HF, n (%) |

Approximately <100 patients: 42 (14.9)

Approximately 100–199 patients: 104 (37.0)

Approximately 200–299 patients: 75 (26.7)

Approximately ≥300 patients: 60 (21.4) |

No. of HF patients (with a history of

HF hospitalization) seen in the outpatient

department per month, n (%) |

Approximately <10 patients: 27 (9.6)

Approximately 10–49 patients: 156 (55.5)

Approximately 50–99 patients: 72 (25.6)

Approximately ≥100 patients: 26 (9.3) |

Table 2.

Background of GP Questionnaire Respondents

| Age, n (%) |

20–29 years: 0 (0)

30–39 years: 12 (8.3)

40–49 years: 45 (31.0)

50–59 years: 56 (38.6)

60–69 years: 28 (19.3)

≥70 years: 4 (2.8) |

| Male sex, n (%) |

132 (91.0) |

| Expertise, n (%) |

Internal medicine: 122 (84.1)

Surgery: 9 (6.2)

Cardiovascular medicine: 83 (57.2)

Respiratory medicine: 10 (6.9)

Gastroenterology: 10 (6.9)

Diabetes medicine: 6 (4.1)

Geriatric medicine: 4 (2.8)

General medicine: 9 (6.2)

Pediatrics: 24 (16.6)

Home medical care: 3 (2.1)

Palliative care: 6 (4.1) |

| Region, n (%) |

Hokkaido region: 1 (1.0)

Tohoku region: 7 (5.0)

Kanto region: 40 (27.0)

Chubu region: 14 (10.0)

Kinki region: 26 (18.0)

Chugoku region: 44 (30.0)

Shikoku region: 4 (3.0)

Kyushu-Okinawa region: 9 (6.0) |

No. of patients with HF (with a history of

HF hospitalization) seen in the outpatient

clinic per month, n (%) |

Approximately <10 patients: 23 (15.9)

Approximately 10–49 patients: 88 (60.7)

Approximately 50–99 patients: 22 (15.2)

Approximately ≥100 patients: 12 (8.3) |

No. of patients with HF (with previous

hospitalization for HF) seen in home visits

per month |

Approximately 2 (0–5) patients per month |

No. of patients with HF (with previous

hospitalization for HF) who received end-of-

life care at home during the past year |

Approximately 0 (0–5) patients per year |

GP, general practitioner; HF, heart failure.

Figure 1

shows the goals of community collaboration in HF between hospital cardiologists and GPs. The first-priority goal for both hospital cardiologists and cardiology GPs was reduced HF hospitalizations and improved mortality rates; non-cardiology GPs prioritized this goal lower than cardiologists (P<0.05). However, hospital cardiologists prioritized reducing the care burden on caregivers less than non-cardiology GPs (P<0.05). Hospital cardiologists prioritized reducing the burden on medical staff and improving job satisfaction higher than both cardiology and non-cardiology GPs (both P<0.05).

Quality of Community Collaboration in HF

Figure 2

shows the quality of community collaboration in HF care. If requesting an outpatient follow-up with a non-cardiology GP after discharge for patients hospitalized with HF, less than half of hospital cardiologists (42%) reported seeing most patients with HF together with a GP, to support patient treatment and management. For patients hospitalized with HF and newly introduced to home medical care or home nursing after discharge, only 34.5% of hospital cardiologists conducted predischarge conferences with both hospital and local healthcare staff for most of these patients with HF. If a predischarge conference was held, only 37.7% of hospital physicians participated in all or a large part of the conference. Participation by GPs was significantly less than participation by hospital cardiologists (P<0.05), and approximately 20% of both cardiology and non-cardiology GPs participated in all or a large part of these conferences. Local coordination and communication systems were not well developed, with only approximately 30% of facilities having a local community-based system that allowed for sharing of information on patients with HF and approximately 20% had consultation services with cardiovascular specialists.

Figure 3

shows the priority of information that hospital physicians provided in a medical information form when requesting an outpatient follow-up after discharge with a GP for patients hospitalized for HF; the Figure also shows the medical information that GPs require from hospital physicians. More than 80% of hospital cardiologists provided medical information such as the etiology of HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), and predischarge echocardiography; non-cardiology GPs prioritized such information less than hospital cardiologists (both P<0.05). However, compared with non-cardiology GPs, hospital cardiologists placed lower priority on information about nursing care and consultation criteria, such as patient and family education content, criteria for when a patient or GP should contact a medical institution, use of nursing care services and living conditions, and advance care planning (ACP) (all P<0.05). In particular, less than 20% of hospital cardiologists included ACP in the medical information form, even though it was desired by more than half of both cardiology and non-cardiology GPs. Additionally, more than 70% of both cardiology and non-cardiology GPs required a discharge summary, but less than half of hospital cardiologists provided a summary in their medical information form.

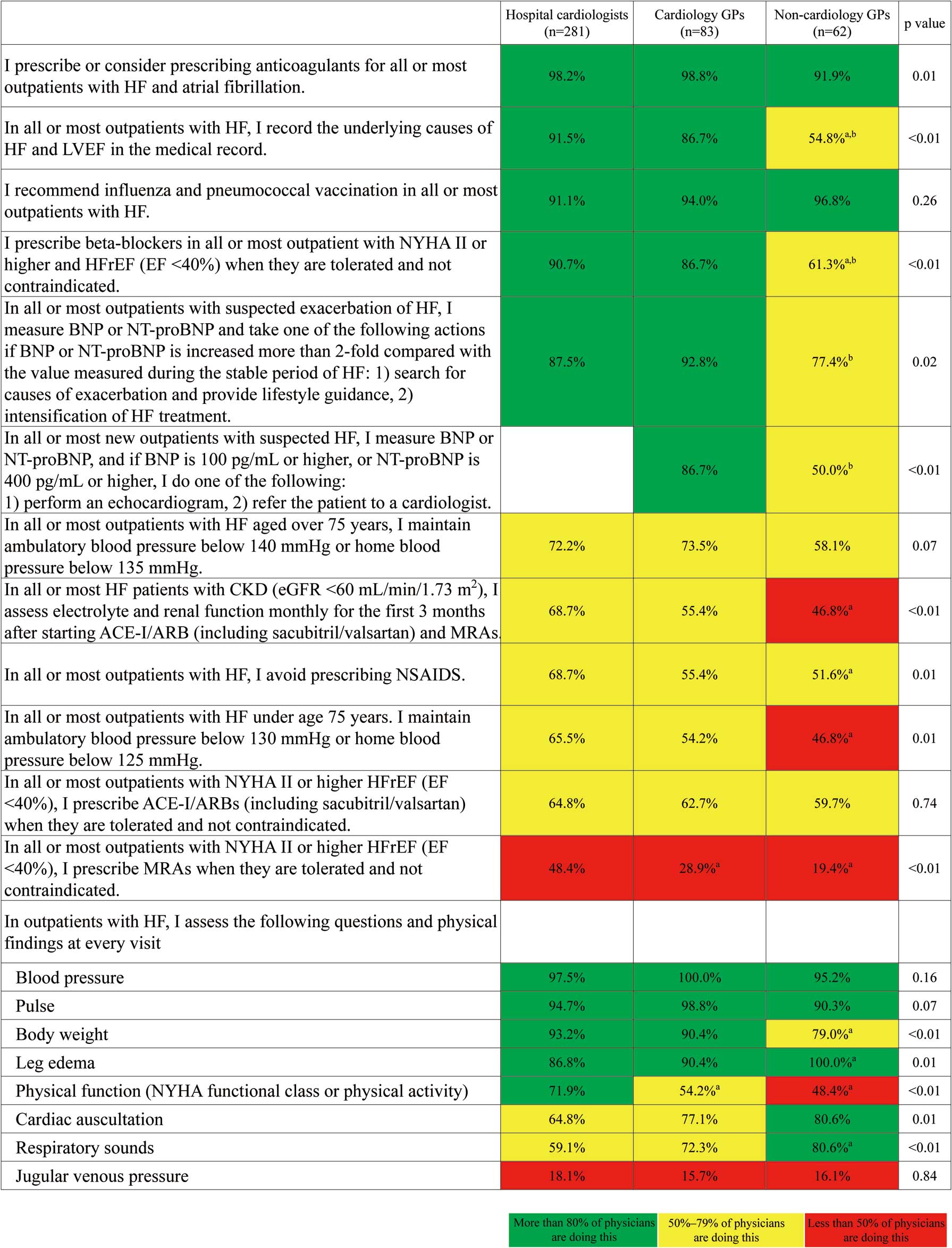

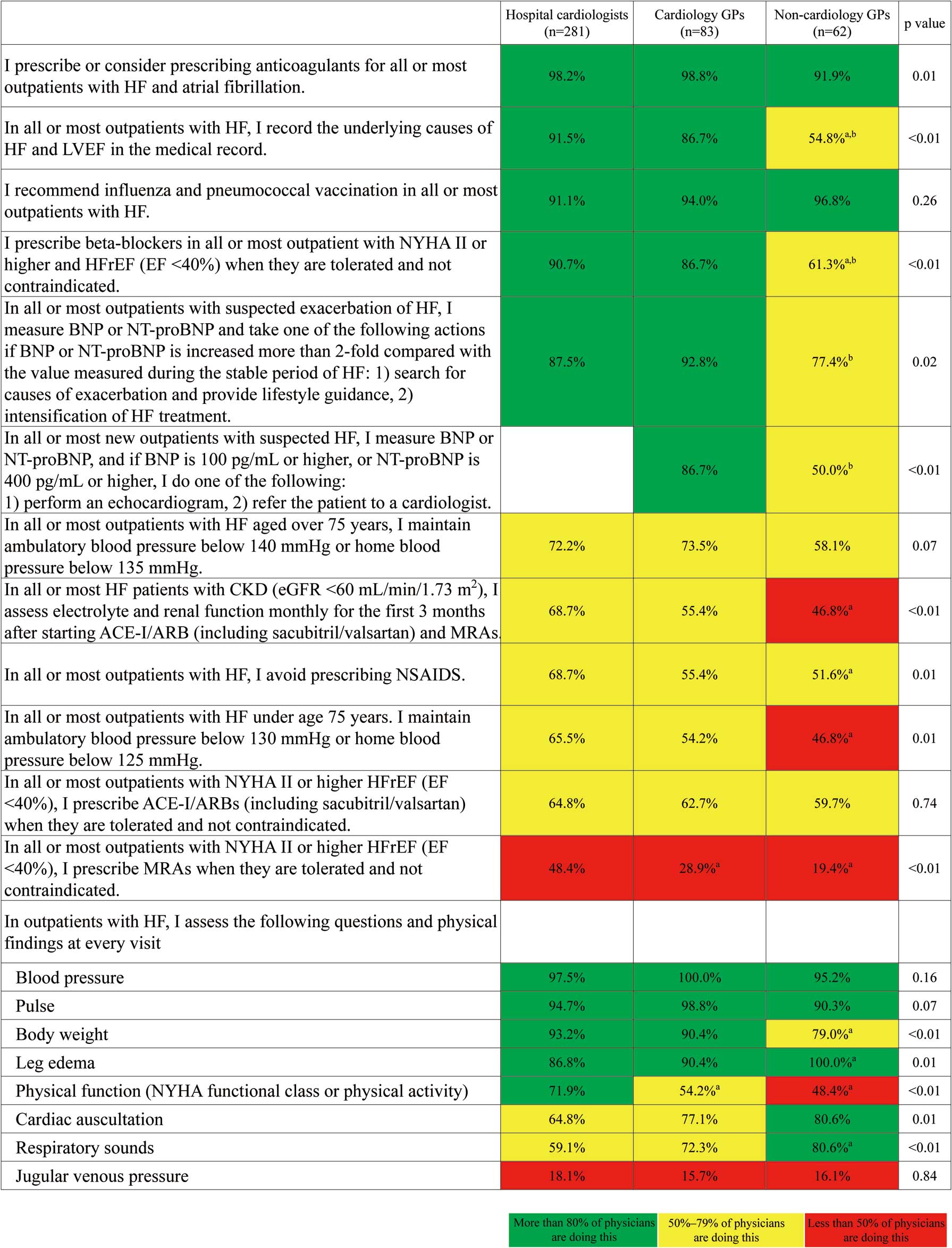

Differences in the quality of medical care for HF between hospital cardiologists and GPs are shown in

Figure 4. Non-cardiology GPs assessed LVEF and prescribed β-blockers and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) for HF with reduced EF (HFrEF) less often than hospital cardiologists. Non-cardiology GPs also achieved blood pressure management goals for patients with HF younger than 75 years and assessed electrolyte and renal function after prescribing renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors less frequently than hospital cardiologists (all P<0.05). Although non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) should be avoided as much as possible in patients with HF because they increase the risk of worsening HF due to fluid retention and worsening renal function,24

non-cardiology GPs avoided prescribing NSAIDS to patients with HF less frequently than hospital cardiologists (P<0.05). Additionally, non-cardiology GPs used B-type natriuretic peptide/N-terminal pro B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP/NT-pro BNP) in outpatient care less often than cardiology GPs (P<0.05). At routine outpatient visits, non-cardiology GPs assessed body weight and physical function less frequently than hospital cardiologists, measures that are necessary for assessing the presence of HF exacerbation (P<0.05). However, hospital cardiologists assessed physical findings such as leg edema and respiratory sounds less often than non-cardiology GPs (both P<0.05). Of note, jugular venous pressure was rarely evaluated, with less than 20% of both hospital cardiologists and GPs conducting this assessment.

Figure 5

shows differences in the quality of multidisciplinary care for HF between hospital cardiologists and GPs. Hospital cardiologists assessed caregivers’ burden of care and certain frailty items less often than non-cardiology GPs (both P<0.05). Less than 30% of hospital cardiologists introduced or considered comprehensive outpatient cardiac rehabilitation for all or most hospitalized patients with HF, and its implementation rate was the lowest among all multidisciplinary HF interventions.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated the following discrepancies in community collaboration for HF. (1) Hospital cardiologists and GPs had different priorities of care and different goals for community collaboration in HF. (2) We identified differences in the quality of medical and nursing care for HF between cardiologists and non-cardiologists. (3) Hospital cardiologists did not provide information that met the needs of GPs, and there were few regions with a community-based system that allowed sharing of information on patients with HF. (4) In the transition to home care, there were few opportunities for direct communication between hospitals and community healthcare staff, and consultation systems were not well developed.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the real-world status of community collaboration for HF in Japan. We used quality indicators developed with the Delphi method for this purpose. This study revealed that hospital cardiologists and cardiology GPs considered reducing HF hospitalization and improving mortality rates as the most important goal of community collaboration in HF; non-cardiology GPs prioritized preventing worsening of HF less, and prioritized supporting patients’ daily life and reducing the burden on their caregivers more, than hospital cardiologists (Figures 1,5). These differences in care goals may be due to hospital cardiologists prioritizing a medically centered treatment model whereas GPs prioritize a person-centered care model.25

As for the information to be included in the medical information form, hospital cardiologists prioritized medical information more than GPs, who considered that information about nursing care and daily living as more important (Figure 3). These differences in priorities affect the quality of HF care; hospital cardiologists are less likely than GPs to provide nursing care, such as utilization of social resources, assessment of frailty, and ACP (Figures 3,5). Additionally, hospital cardiologists are less interested in rehabilitation, as evidenced by the low rates of implementation or consideration of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation (Figure 5); this is consistent with our previous report.26

However, non-cardiology GPs placed a lower priority on standard medical care in HF (Figure 4). Thus, quality improvement in HF care is required among both hospital cardiologists and GPs. To eliminate gaps in the quality of HF care, it is necessary to develop educational programs and training systems that enable both hospital cardiologists and GPs to acquire basic knowledge of HF and nursing care and to standardize the quality of HF care.4,22

From this viewpoint, our research group has developed a guidebook that can be used by GPs and other medical and care staff, which may contribute to improving the quality of HF care in the community.27

Based on the results of this study, an ideal community collaboration would be one in which cardiologists supported treatment and GPs supported patients’ daily life concerns as functionally differentiated interventions that effectively utilize the strengths of each and compensate their weaknesses. It has been reported that clinical outcomes are improved when hospital cardiologists and GPs work together rather than each seeing patients with HF separately from the other.28

However, this survey also revealed that during the vulnerable period after hospital discharge,29

less than half of hospital cardiologists (42%) saw all or most patients with HF together with GPs to support patients’ treatment and management (Figure 2). Additionally, when introducing home medical care or home nursing after discharge, only 34.5% of hospital cardiologists conducted predischarge conferences with hospital and local healthcare staff for all or most patients with HF (Figure 2). Furthermore, physicians’ participation in such conferences was low, suggesting that there are few opportunities for direct communication with healthcare staff in the community. According to the comments of survey respondents, the barriers to collaboration between hospital physicians and GPs include the difficulty for patients to visit 2 locations (i.e., the hospital and a clinic) because most patients are old and frail or have no caregivers. Additionally, it is difficult to conduct conferences owing to difficulties in coordinating times among hospital and community-based staff because of a lack of staff. These problems are challenging to solve through efforts of both the medical and care staff. Therefore, it may be necessary to develop a model for collaboration and information sharing without the need for face-to face communication between medical professionals and patients/families, using clinical pathways and information and communication technology (ICT), as a possible solution.4,30

The electronic health record is one of the effective ICT tools and may contribute to the sharing of information between hospitals and clinics and to improved efficiency in HF management. In addition, a mobile personal health record linked with a wearable device could replace the paper-based HF handbook and allow patients, families, and healthcare providers to share information such as blood pressure, pulse rate, and body weight, which may contribute to early intervention when HF worsens.31

However, only approximately 30% of regions in Japan have introduced collaborative systems (Figure 2).

When direct communication is difficult, it is important to share information in writing using a medical information form.4,9

However, we found discrepancies in priority regarding this information between hospital cardiologists and GPs, and hospital cardiologists may not provide information that meets the needs of GPs (Figure 3). Additionally, there are only a few facilities that have a consultation system for professional staff (Figure 2). Therefore, it is necessary to standardize the provision of medical information9

and efficient collaboration and consultation systems; in particular, systems that include the use of clinical pathways and ICT need to be developed.4,22

The current study showed that GPs were more interested in ACP than hospital cardiologists (Figure 3). In community practice settings, GPs may be better able to listen to the actual wishes of patients and their families about medical treatment and care. If GPs take the initiative to promote ACP, they can provide better care for patients and their families.

Study Limitations

In a previous questionnaire survey conducted in Japan, 56% of GPs reported that they would prefer to avoid managing symptomatic HF patients in the clinic.32

However, GP respondents in this study seemed to be more cooperative about HF care. Because the questionnaire for this study was requested through the research group’s home page and various academic societies, the physicians who responded to the questionnaire survey were likely to be highly interested in HF treatment and regional cooperation. Therefore, sample bias must be taken into account when interpreting the results. In addition, regional characteristics of the respondents also need to be considered. Differences in healthcare systems in the regions may affect the quality of HF care. Furthermore, the age of doctors is also associated with the quality of HF care. Subgroup analysis according to the age of responders showed that, among hospital cardiologists, responders aged under 40 years old more often participated in predischarge conferences and prescribed MRAs than those aged over 60 years old (all P<0.05), but were less likely to implement cardiac rehabilitation than those in their 40 s and 50 s (all P<0.05) (data not shown). Thus, more detailed analysis of physician background, region, etc. is necessary to promote regional cooperation for HF. Finally, although this survey was limited to physicians, it is essential to collaborate with other professionals in promoting community collaboration. Differences in the quality of HF care provided by staff other than physicians should also be examined in the future.

In conclusion, this study clarified the actual status and problems in community collaboration for HF in Japan, especially differences in priorities for HF management between hospital cardiologists and GPs. Our data will contribute to the future direction and promotion of community collaboration and to improving the quality of medical and nursing care for patients with HF.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following collaborators for their cooperation in the survey: the Japan Heart Failure Society, the Japan Primary Care Association, the Japan Association of Home Health Care, the Japan Medical Association, the research team members in provision of HF care centered on GPs in the community (SupplementaryAppendix), and all respondents to the questionnaire. We thank Analisa Avila, ELS, of Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Data Availability

The deidentified participant data cannot be shared because the data contain information on a sensitive issue.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (KAKENHI; No. 20K08403) and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan (No. 18062589).

Disclosures

Y.K. received research grants from St. Jude Medical Japan Co., Ltd., Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Boston Scientific Co., Ltd., Johnson & Johnson, Biotronik Japan Inc., Japan Lifeline Co., Ltd., Astellas, Teijin Pharma Ltd., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Co., Ltd., Fukuda Denshi, Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Public Health Research Foundation, Nihon Kohden Co., Ltd., and Novartis Co., Ltd. K. Kadota received lecture fees from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd. K. Kamiya received research grants from Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd. S.K. received lecture fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb Co., Ltd., and received research grants from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd. E.N. received lecture fees from Boehringer Ingelheim Co., Ltd, and research grants from Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Nippon Shinyaku Co., Ltd., Amgen Inc Co., Ltd., Nihon Medi-Physics Co.,Ltd., and Bayer Co., Ltd. T.S. received lecture fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd. M.I. received lecture fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi-Sankyo Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Pfizer Japan Inc. Co., Ltd.

IRB Information

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sakakibara Heart Institute (No. 20-047).

Supplementary Files

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-21-0335

References

- 1.

Yasuda S, Miyamoto Y, Ogawa H. Current status of cardiovascular medicine in the aging society of Japan. Circulation 2018; 138: 965–967.

- 2.

Shimokawa H, Miura M, Nochioka K, Sakata Y. Heart failure as a general pandemic in Asia. Eur J Heart Fail 2015; 17: 884–892.

- 3.

Yaku H, Ozasa N, Morimoto T, Inuzuka Y, Tamaki Y, Yamamoto E, et al. Demographics, management, and in-hospital outcome of hospitalized acute heart failure syndrome patients in contemporary real clinical practice in Japan: Observations from the prospective, multicenter Kyoto Congestive Heart Failure (KCHF) Registry. Circ J 2018; 82: 2811–2819.

- 4.

Albert NM, Barnason S, Deswal A, Hernandez A, Kociol R, Lee E, et al; American Heart Association Complex Cardiovascular Patient and Family Care Committee of the Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Reasearch. Transitions of care in heart failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circ Heart Fail 2015; 8: 384–409.

- 5.

Paz-Pascual C, Artieta-Pinedo I, Grandes G, ema QG. Consensus on priorities in maternal education: Results of Delphi and nominal group technique approaches. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19: 264.

- 6.

Tsutsui H, Isobe M, Ito H, Ito H, Okumura K, Ono M, et al; Japanese Circulation Society and the Japanese Heart Failure Society Joint Working Group. JCS 2017/JHFS 2017 Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: Digest version. Circ J 2019; 83: 2084–2184.

- 7.

Ezekowitz JA, O’Meara E, McDonald MA, Abrams H, Chan M, Ducharme A, et al. 2017 Comprehensive update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of heart failure. Can J Cardiol 2017; 33: 1342–1433.

- 8.

Bradley EH, Curry L, Horwitz LI, Sipsma H, Wang Y, Walsh MN, et al. Hospital strategies associated with 30-day readmission rates for patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013; 6: 444–450.

- 9.

Al-Damluji MS, Dzara K, Hodshon B, Punnanithinont N, Krumholz HM, Chaudhry SI, et al. Hospital variation in quality of discharge summaries for patients hospitalized with heart failure exacerbation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015; 8: 77–86.

- 10.

Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, Miller DC, Potter J, Wears RL, et al; American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physician, Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med 2009; 24: 971–976.

- 11.

Yamamoto K, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Kinugasa Y, Iida Y, Kamiya K, Kihara Y, et al; Japanese Heart Failure Society Expert Consensus Writing Committee. Japanese Heart Failure Society 2018 Scientific Statement on nutritional assessment and management in heart failure patients. Circ J 2020; 84: 1408–1444.

- 12.

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, et al; Authors/Task Force Members and Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail 2016; 18: 891–975.

- 13.

Writing Committee Members, Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2013; 128: e240–e327.

- 14.

NICE guidance. Chronic heart failure in adults: Diagnosis and management (2018). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106 (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 15.

Healthcare improvement Scotland. Heart disease standard. http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/standards_and_guidelines/stnds/heart_disease_standards.aspx (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 16.

Wenger NS, Solomon D. Appendix to Application of ACOVE-3 Quality Indicators to Patients with Advanced Dementia and Poor Prognosis (Appendices 1 & 2 and Figures 1 & 2). https://www.rand.org/pubs/working_papers/WR515z2.html (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 17.

The Canadian Cardiovascular Society qualty indicators E-catalogue for heart failure: A CCS Consensus Document. https://ccs.ca/app/uploads/2020/12/HF_QIs_2019_update_final.pdf (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 18.

Mizuno A, Miyashita M, Hayashi A, Kawai F, Niwa K, Utsunomiya A, et al. Potential palliative care quality indicators in heart disease patients: A review of the literature. J Cardiol 2017; 70: 335–341.

- 19.

Kihon Checklist. http://jssf.umin.jp/pdf/Kihon%20Checklist.pdf (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 20.

Japanese Geriatrics Society. Guidelines for safe pharmacotherapy of the elderly (2015). https://www.jpn-geriat-soc.or.jp/info/topics/pdf/20170808_01.pdf (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 21.

Japanese Society of Heart Failure Prevention Committee. Notes on heart failure treatment using blood BNP and NT-proBNP levels. http://www.asas.or.jp/jhfs/topics/bnp201300403.html (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 22.

McDonagh TA, Blue L, Clark AL, Dahlstrom U, Ekman I, Lainscak M, et al; European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Committee on Patient Care. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure Association Standards for delivering heart failure care. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: 235–241.

- 23.

Izawa H, Yoshida T, Ikegame T, Izawa KP, Ito Y, Okamura H, et al; Japanese Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation Standard Cardiac Rehabilitation Program Planning Committee. Standard cardiac rehabilitation program for heart failure. Circ J 2019; 83: 2394–2398.

- 24.

Page RL 2nd, O’Bryant CL, Cheng D, Dow TJ, Ky B, Stein CM, et al; American Heart Association Clinical Pharmacology and Heart Failure and Transplantation Committees of the Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Drugs that may cause or exacerbate heart failure: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 134: e32–e69.

- 25.

Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, Taft C, Dudas K, Schaufelberger M, et al. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: The PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1112–1119.

- 26.

Kamiya K, Yamamoto T, Tsuchihashi-Makaya M, Ikegame T, Takahashi T, Sato Y, et al. Nationwide survey of multidisciplinary care and cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure in Japan: An analysis of the AMED-CHF Study. Circ J 2019; 83: 1546–1552.

- 27.

Guidebook on heart failure treatment for general practitioners and medical care staff. https://plaza.umin.ac.jp/isobegroup/ (accessed March 22, 2021).

- 28.

Lee DS, Stukel TA, Austin PC, Alter DA, Schull MJ, You JJ, et al. Improved outcomes with early collaborative care of ambulatory heart failure patients discharged from the emergency department. Circulation 2010; 122: 1806–1814.

- 29.

Desai AS. The three-phase terrain of heart failure readmissions. Circ Heart Fail 2012; 5: 398–400.

- 30.

Aronow WS, Shamliyan TA. Comparative effectiveness of disease management with information communication technology for preventing hospitalization and readmission in adults with chronic congestive heart failure. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2018; 19: 472–479.

- 31.

Kao DP, Trinkley KE, Lin CT. Heart failure management innovation enabled by electronic health records. JACC Heart Fail 2020; 8: 223–233.

- 32.

Tsukada YT, Kodani E, Asai K, Yasutake M, Seino Y, Shimizu W. Status of medical care and management requirements of elderly patients with heart failure in a comprehensive community health system: Survey of general practitioners’ views. Circ Rep 2021; 3: 77–85.