論文ID: CJ-21-0572

論文ID: CJ-21-0572

Background: Danon disease is typically associated with cardiomyopathy and ventricular pre-excitation. The study aimed to characterize the clinical profile of Danon disease, analyze electrocardiographic (ECG) and electrophysiologic features, and investigate their association with Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome and fasciculoventricular pathways (FVPs).

Methods and Results: Clinical course, family history, ECG and electrophysiological data were collected from 16 patients with Danon disease. Over 0.4–8 years of follow up, 1 female patient died suddenly, and 5 male patients died of progressive heart failure by age 13–20 years. Family history analysis revealed that 3 mothers experienced hospitalization or death for heart failure at age 28–41 years. There was 100% penetrance for ECG abnormalities in 13 patients with original ECGs. Short PR intervals and delta waves were present in 9 and 8 patients, respectively. There were significant age-associated increases in the QRS complex width (r=0.556, P=0.048) and the number of leads with notched QRS (r=0.575, P=0.04). Four patients who underwent electrophysiological studies all had FVPs, and 2 of them still had left-side atrioventricular pathways.

Conclusions: Danon disease causes a malignant clinical course characterized by early death caused by heart failure in both genders and progressive ECG changes as patients age. The pre-excited ECG pattern is related to FVPs and WPW, which is suggestive of extensive cardiac involvement.

Danon disease, caused by mutations in the gene of lysosome-associated membrane protein 2 (LAMP2),1,2 is an X-linked dominant multisystem disorder predominantly affecting the heart.3–5 Cardiac involvement in Danon disease typically manifests as cardiomyopathy. Male patients demonstrate a high prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy (88%), whereas female patients show an approximately equal risk for either dilated (28%) or hypertrophic (33%) phenotypes.6 The rarity of this disease has limited understanding of the clinical phenotypes. Ventricular pre-excitation is the most frequently observed electrocardiographic (ECG) abnormality in Danon disease, occurring in 68.2% of men and 26.7% of women,6 and therefore plays an essential role in distinguishing a hypertrophic cardiac phenotype associated with LAMP2 mutations from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to genetic defects of sarcomeric proteins.7 In the past, the high frequency of a pre-excited ECG pattern in Danon disease was always attributed to Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome caused by antegrade atrioventricular (AV) accessory connections. However, recent reports of limited case series suggested that this usual manifestation on ECG was associated with fasciculoventricular pathways (FVPs).8,9 Although the ECG and electrophysiologic features of both WPW and FVPs have been well characterized in patients with a normal structural heart, they have not been clearly described in those patients with Danon disease. The purpose of this study was to characterize the clinical profile of patients with Danon disease, analyze ECG and electrophysiologic features, and investigate their association with WPW and FVPs.

Patients with a diagnosis of Danon disease, confirmed by the identification of a pathogenic LAMP2 mutation on genetic testing, were included in this study from 3 different centers. Based on this criteria, we identified 16 patients with Danon disease, including 13 previously identified cases.10–12 Diagnosis of Danon disease was based on genetic confirmation of LAMP2 deficiency. Demographic and clinical data were collected. The current clinical status of these cases and their family members was reexamined by 3 authors (Y.L., L.F. and J.H.). ECG analysis was performed if original ECG data were available. Invasive electrophysiological studies were performed according to standard protocols. See Supplementary File for details of echocardiographic images, ECG analysis, electrophysiological studies and statistics. The investigation was approved by the ethics committees of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed and written consent was obtained from all study subjects.

Continuous variables were reported as mean±standard deviation or median and minimum and maximum values. Categorical variables were summarized as counts. Pearson correlation and linear regression was used to investigate ECG variables over age. Significance was defined as a P<0.05.

Clinical, demographic and outcome data were compiled for the 16 patients and summarized in Table 1. The 6 female and 10 male patients were aged between 0.25 and 43 years (median 16.5 years) at diagnosis. Clinical recognition in 9 patients occurred by virtue of symptoms (chest pain, dyspnea, muscle weakness or aborted cardiac arrest), in 3 because of heart murmur or mental retardation, and in 4 due to family screening. All patients presented with left ventricular hypertrophy on echocardiography. Maximum septal wall thickness was 9–36 mm (21±8mm). Five patients had reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (22–46%) at admission and 4 of them had a dilated left ventricular end-diastolic cavity (53–65 mm). Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction was present at rest in 4 patients (gradient, 11–50 mmHg). Elevated serum enzymes including creatine kinase, liver transaminase and/or lactate dehydrogenase were noted in all patients except 3 asymptomatic women. One patient had clinically documented supraventricular tachycardia. One patient had an aborted cardiac arrest due to spontaneous ventricular fibrillation recorded by ambulatory ECG monitoring. Intermittent AV block was noted in a patient during Holter monitoring. Eight frameshift mutations, 7 non-sense mutations and 1 splicing mutation of the LAMP2 gene were present in these patients.

| Age (years) / Gender |

Presentation | Maximal IVS/LVPW thicknesses, LV size (mm), and LVEF (%) |

LVOT gradient (mmHg) |

Arrhythmias | Serum enzymes elevated |

FH | FU (years) |

Death / age (years) |

Mutation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19/M | Dyspnea | 19/24/41/61 | 0 | AVB | + | + | 6 | − | p. L325PfsX24 |

| 2 | 23/M | Chest pain | 33/31/32/62 | 11 | SVT | + | − | 4 | − | IVS 1-2A > G |

| 3 | 17/M | Aborted CA; muscle weakness |

29/23/42/45 | 0 | VF | + | − | 2 | +/19 | p. V15RfsX19 |

| 4 | 16/M | Dyspnea | 16/16/53/46 | 0 | AVB, VT | + | − | 2 | − | p. R293X |

| 5 | 15/M | Chest pain | 36/25/60/44 | 0 | − | + | + | 1 | +/16 | p. Q353X |

| 6 | 10/F | Dyspnea | 18/29/37/78 | 50 | − | + | − | 4 | +/14 | p. S250X |

| 7 | 2/F | Heart murmur | 18/22/26/90 | 42 | AF | + | − | 6 | − | p. G22X |

| 8 | 5/M | Mental retardation | 9/14/31/77 | 0 | − | + | + | 1 | − | p. V114KfsX40 |

| 9 | 18/M | Chest pain; dyspnea |

28/30/30/80 | 50 | − | + | + | 2 | +/20 | p. T63TfsX10 |

| 10 | 20/F | None | Mild LVH | 0 | − | − | + | NA | NA | p. T63TfsX10 |

| 11 | 43/F | None | Mild LVH | 0 | − | − | + | NA | NA | p. T63TfsX10 |

| 12 | 18/M | Chest pain; muscle weakness |

19/13/65/27 | 0 | − | + | + | 0.4 | +/18 | p. A342DfsX3 |

| 13 | 42/F | None | Mild LVH | 0 | − | − | + | 8 | − | p. A342DfsX3 |

| 14 | 13/M | Dyspnea; muscle weakness |

19/17/57/22 | 0 | − | + | + | 0.5 | +/13 | p. Q240X |

| 15 | 2/F | None | 10/7/28/67 | 0 | − | + | + | 5 | − | p. Q240X |

| 16 | 0.25/M | Heart murmur | 16/16/19/80 | 0 | − | + | − | 6 | − | p. L156X |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AVB, atrioventricular block; CA, cardiac arrest; F, female; FH, family history; FU, follow up; IVS, intraventricular septum; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LVPW, left ventricular posterior wall; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; M, male; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia; +, positive; −, negative.

Over the subsequent 0.4–8 years, 1 female patient (No. 6 in Table 1) died suddenly from unknown causes 4 years after her initial presentation and 5 male patients (No. 3, 5, 9, 12 and 14 in Table 1) died of progressive heart failure 0.4–2 years after initial diagnosis, by age 13–20 years (Table 1). Echocardiographic assessment in patient 5 before his death demonstrated progressive left ventricular cavity enlargement and relative wall thinning with an end-diastolic dimension of 70 mm, diffusely hypokinetic left ventricular wall motion with an ejection fraction of 25% and right ventricular involvement with a superior-inferior dimension of 89 mm and spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in the right ventricular apex (Supplementary Figure 1). Patient 1 was recently admitted to a local hospital because of progressive clinical deterioration with cardiac function of New York Heart Association functional class IV. Patient 4 developed Wenckebach block 2 years after successful ablation of left-side accessory pathways (Figure 1), and implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation (ICD) was performed for primary prevention of sudden cardiac death. After ICD implantation, serial device interrogations found transient ventricular tachycardia with no need of appropriate ICD therapies. Patients 10 and 11 were lost to follow up. Patient 13 complained of chest pain and shortness of breath at the age of 50 years. The remaining 5 patients were still clinically stable and no progressive cardiac conduction system diseases were observed. Recent echocardiographic assessment in patients 2, 7, 8, and 16 did not find any systolic dysfunction, left ventricular cavity enlargement and relative wall thinning; however, patient 7 developed atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response at the age of 8 years.

Surface 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) of patient 4. (A) An ECG of patient 4 at initial presentation shows sinus rhythm, short PR intervals, obvious delta waves, right bundle branch block QRS morphologies, notched QRS complex and deep negative T waves (25 mm/s, 5 mm/mV). (B) Surface ECG of patient 4 demonstrates Wenckebach block 2 years after successful ablation of left-side accessory pathways (25 mm/s, 10 mm/mV).

The 16 patients were from 12 unrelated families. Two mothers of patients 1 and 5 probably carried the LAMP2 mutation, given that they died from congestive heart failure at the age of 41 years and 35 years, respectively. Patient 8 and his mother were found to have the same LAMP2 mutation. The woman experienced severe heart failure at age 28 years. The mother of patients 14 and 15 was asymptomatic and genetically affected. She had no ECG and echocardiographic abnormality at initial presentation. Both mothers of patients 2 and 3 had no cardiac symptoms and did not undergo genetic testing. The genetic defects in patients 4, 6, 7 and 16 were considered to be spontaneous because genetic screening was negative in their healthy parents. The symptomatic penetrance in 4 mothers with proven or likely diagnosis of Danon disease and 6 female patients was approximately 50% (5/10).

ECG During Sinus RhythmOriginal 12-lead ECG during sinus rhythm was available in 13 patients and ECG findings are summarized in Table 2. Of the 13 patients, 2 showed sinus bradycardia with a resting heart rate <60 bpm. A short PR interval (<120 ms) was present in 9 patients. Ventricular pre-excitation, including the presence of a delta wave, was identified in 8 patients. The QRS morphology of lead V1 was a R pattern in 1 patient, RS in 2 and rS in the remaining patients. Depolarization abnormalities with notched QRS configuration were observed in 12 patients and the number of ECG leads with notched QRS ranged from 1 to 12 in these patients (Figure 2A). Mean QRS complex width was 140±45 ms (range 60–222 ms) and 7 had QRS duration of >140 ms; mean left ventricular voltage was 9.5±3.5 mV (range 5.4–16.3 ms); corrected QT intervals averaged 47±57 ms (range 391–569 ms); and ECG criteria for left ventricular hypertrophy and QT interval prolongation (>440 ms) were present in 13 and 9 patients, respectively. There were significant age-associated increases in the QRS complex width (r=0.556, P=0.048) and the number of ECG leads with notched QRS (r=0.575, P=0.04) (Figure 2B). There was 100% penetrance for ECG abnormalities (short PR intervals, delta waves, high voltage, and/or abnormal QRS). After a bypass tract was ablated, patient 4 demonstrated normal PR intervals, slight delta waves and an RSR pattern in lead V1 (Figure 1).

| HR (beats/ min) |

PR (ms) |

VP | V1 | nQRS (N) |

QRS width (ms) |

SV1 + RV5 (mV) |

QT/QTc (ms) |

AH (ms) |

HV (ms) |

FVP-V (ms) |

AVNERP (ms) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50 | 192 | + | rS | + (9) | 160 | 7.4 | 460/419 | ||||

| 2 | 62 | 90 | + | rS | + (8) | 150 | 16.3 | 472/479 | 54 | 30 | 10 | 260 |

| 3 | 68 | 94 | + | rS | + (10) | 180 | 7.0 | 536/569 | 40 | 22 | 8 | 210 |

| 4 | 79 | 80 | + | R | + (4) | 176 | 5.4 | 470/538 | ||||

| 89 | 162 | + | rS | + (1) | 144 | 3.7 | 418/510 | 116 | 45 | 14 | 440 | |

| 5 | 58 | 110 | + | rS | + (10) | 222 | 14.0 | 561/552 | 102 | 14 | 0 | 310 |

| 6 | 85 | 122 | − | rS | + (2) | 122 | 7.6 | 398/473 | ||||

| 7 | 85 | 94 | + | rS | − | 136 | 12.1 | 434/516 | ||||

| 8 | 69 | 96 | − | rS | + (1) | 92 | 7.8 | 366/392 | ||||

| 9 | 63 | 100 | + | rS | + (4) | 150 | 14.0 | 400/420 | ||||

| 10 | 73 | 105 | − | rS | + (1) | 95 | 5.9 | 400/441 | ||||

| 14 | 75 | 100 | + | RS | + (12) | 190 | 10.6 | 420/470 | ||||

| 15 | 75 | 120 | − | RS | + (1) | 60 | 5.8 | 350/391 | ||||

| 16 | 89 | 138 | − | rS | + (2) | 88 | 9 | 382/464 |

These values of patient 4 were measured before and after ablation of the left-side accessory pathway. AVNERP, atrioventricular node effective refractory period; HR, heart rate; N, number of leads with notched QRS; nQRS, notched QRS; VP, ventricular pre-excitation.

(A) Electrocardiograms (ECGs; 25 mm/s, 2.5 mm/mV) of patient 5. An ECG of patient 5 shows sinus rhythm, short PR intervals, slight delta waves, a rS pattern in lead V1, almost global notched QRS complex (arrows) and deep negative T waves. 25 mm/s, 5 mm/mV. (B) Trend of ECG indexes according to age. LV, left ventricle; nQRS, notched QRS.

Invasive electrophysiological studies were performed in 4 patients with ventricular pre-excitation on surface ECG for diagnosis and possible ablation of accessory pathways. The patient with a predominantly positive R wave in lead V1 had a broad accessory pathway with multiple ventricular and atrial insertions (Figure 3). After successful ablation of the accessory pathway located on the posterior mitral anulus (Supplementary Figure 2), delta waves were still present in this patient (Figure 4C). Further testing revealed that the delta waves were due to the presence of an FVP (Figure 4D,E).

Intracardiac tracings obtained from an electrophysiological study in patient 4. (A) CS proximal pacing results in a change of QRS morphology. Note that the atrial and ventricular signals are fused in the CS during both CS pacing and sinus rhythm. These findings suggest that this patient has multiple antegrade AV pathways or a broad pathway with multiple ventricular insertions. (B) Ventricular pacing demonstrates VA conduction with variable atrial activation sequence. The earliest retrograde atrial signal is initially seen on the His bundle electrogram, and subsequently occurs in the middle, proximal and distal CS, respectively (long-dotted lines used as references). AV, antegrade atrioventricular; CS, coronary sinus; H, His bundle; VA, ventriculoatrial; RV, right ventricular.

Intracardiac tracings and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) after ablation of the large pathway showing the evidence of a fasciculoventricular pathway (FVP) in patient 4. (A) Ventricular pacing demonstrates decremental and concentric ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction. (B) Atrial pacing demonstrates decremental antegrade atrioventricular (AV) conduction without changing QRS morphologies and HV intervals. (C) The surface ECG shows sinus rhythm, normal PR intervals, initial QRS complex slurring (arrows) and right bundle branch block morphology. (D) The tracing shows normal AH and HV intervals during sinus rhythm. Note that the local ventricular activation recorded from the His bundle region is earlier than that from the right ventricular apex and precedes the onset of surface QRS complex. (E) Intravenous adenosine prolongs PR and AH intervals without change in the degree of ventricular pre-excitation on surface ECG and HV intervals. Arrows point to the FVP depolarization. A, atrial potentials; H, His bundle.

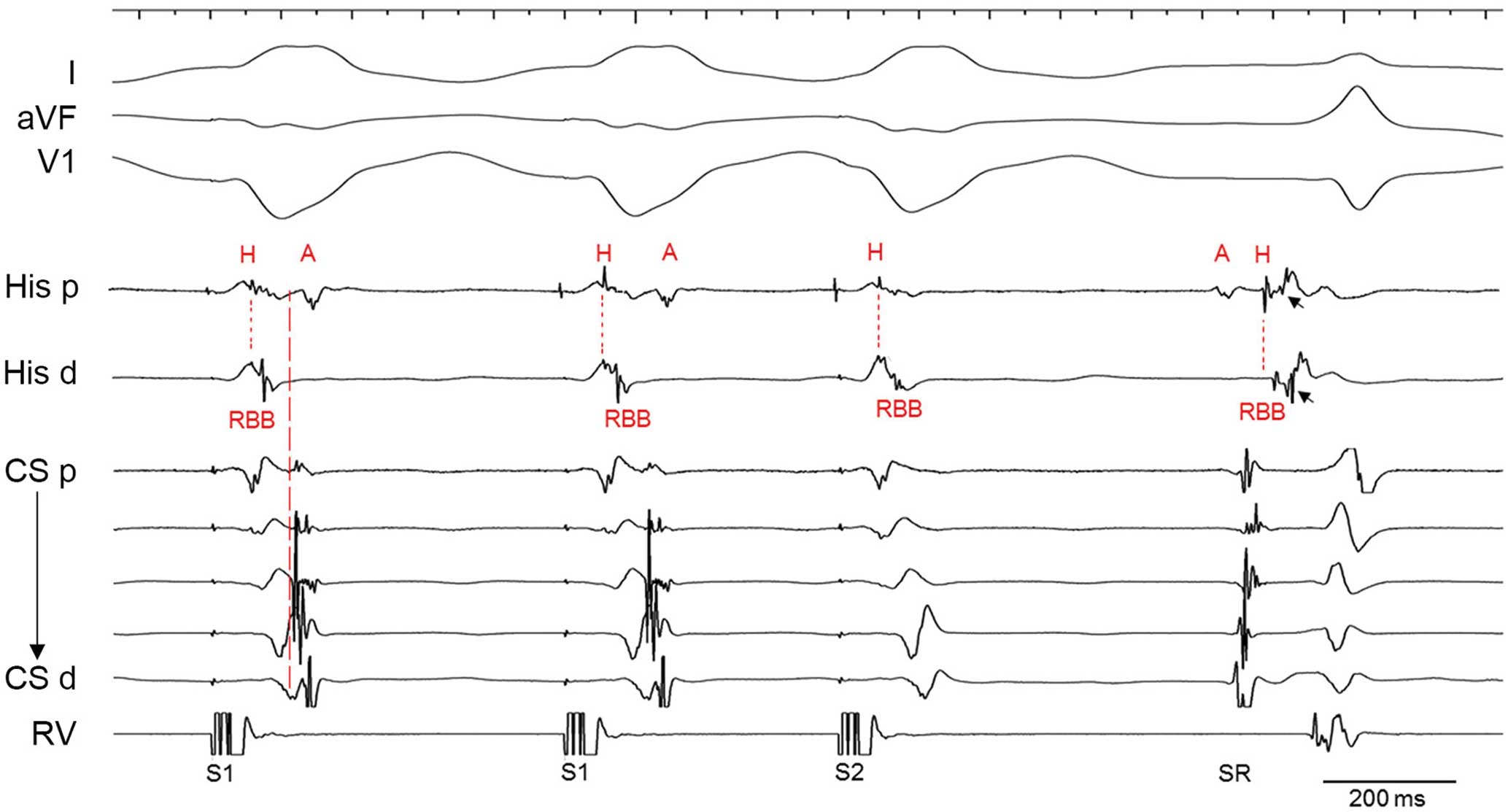

The remaining 3 patients all had FVPs and one of them who had documented supraventricular tachycardia presented with intermittent eccentric ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction during ventricular pacing, suggestive of a retrograde AV pathway (Figure 5). The pathway was located at the left-side free wall according to the earliest retrograde atrial depolarization. The retrograde conduction property of the FVP in this case was also determined according to a similar activation sequence of His bundle to right bundle during ventricular pacing, even at the beat of VA block and sinus rhythm.

Intracardiac tracing showing the evidence of a retrograde antegrade atrioventricular (AV) pathway and a fasciculoventricular pathway (FVP) in patient 2. Ventricular pacing demonstrates intermittent eccentric ventriculoatrial (VA) conduction with the earliest atrial activation in the middle coronary sinus (CS) electrogram, suggestive of the presence of a left-side AV pathway. Note that the activation sequence of the His bundle and right bundle during ventricular pacing, even at the beat of VA block is similar to sinus activation in this case, suggesting the presence of an FVP with a property of retrograde conduction. FVs take off from the His bundle (a schematic diagram of FVPs is provided in the Supplementary Figure 3). In the presence of an FVP, ventricular activation proceeds through the FVP to the His bundle, as well as through the distal RBB to the proximity during ventricular pacing. A H-RBB activation sequence may occur if ventricular pacing at the basal portion of the right ventricle or closer to the His bundle area than the distal RBB. Arrows point to the FVP depolarization. A, atrial potentials; H, His bundle; RBB, right bundle branch.

A discrete FVP depolarization spike was recorded at the His bundle area in all 4 patients (Figures 4E,5 and 6), with a local FVP potential to delta waves interval of 0–14 ms (mean 8±6 ms). Local ventricular activation recorded from the His bundle region was taken earlier than that from the right ventricular apex and preceded the onset of surface delta waves (Figure 4D). The AH intervals ranged between 40 and 116 ms (mean 78±37 ms). The HV (H-delta) intervals ranged from 14 to 45 ms (mean 28±13 ms). Details of these parameters were described in Table 2.

Recordings of fasciculoventricular pathway (FVP) potentials in patient 5. The FVP depolarization (arrows) occurs after the His bundle depolarization. H, His bundle.

The present study provides insights into the clinical course, as well as ECG and electrophysiological characteristics of Danon disease. As previously demonstrated, Danon disease causes rapid progression to cardiac death after initial diagnosis in male patients.4 In our study, 5 male patients died of heart failure in their second decade of life, only 0.4–2 years after initial diagnosis, suggestive of the importance of early identification for this entity. Of note, echocardiographic assessment in 1 patient before his death demonstrated right ventricular involvement with ventricular cavity enlargement and spontaneous echocardiographic contrast in the right ventricular apex. These findings indicate that Danon disease affects both the left and right ventricles and patients may have an elevated risk of thromboembolic events. Oral anticoagulation treatment should be considered in such patients with severely impaired ventricular function.

Because of the X-linked nature of inheritance, male patients with Danon disease present with nearly 100% of penetrance, whereas female patients often show incomplete penetrance with variable expressivity from asymptomatic to severe presentation. Typically, female patients with Danon disease are affected later and less severely than male patients. A systematic review of Danon disease revealed that symptom onset was 15 years later for female patients.3 Our data suggested that Danon disease could also lead to an early sudden death during adolescence in female patients. The potential mechanism for phenotypic difference in females is thought to be associated with skewed X-chromosome inactivation.13 Additionally, mutation types might be also be related to clinical severity of Danon disease. The systematic review of Danon disease found that protein-truncating mutations (non-sense, frameshift, and large deletion/duplication mutations) caused early symptom onset for both male and female patients, whereas missense mutations produced a relatively muted phenotype.3 In our case series, most mutations were non-sense or frameshift mutations, therefore likely resulting in severe and early onset classical phenotypes in these patients.

Theoretically, the X-linked LAMP2 mutations in male patients should be maternally transmitted. Family history analysis in our study revealed affected mothers who experienced hospitalization or death because of heart failure did so during adulthood. These observations underscore a significant mortality risk in both male and female patients with Danon disease. Because of the rapidly progressive nature and an especially poor prognosis of Danon disease, regular echocardiographic evaluations of cardiac structure and function are critical in these patients. Heart transplantation, the only life-saving therapy for Danon disease to date, should be considered once heart failure occurs.

Malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias were a possible cause of sudden death in patients with Danon disease. In a study by Jhaveri et al, 6 of 10 patients with Danon disease had non-sustained ventricular tachycardia.8 Another study by Konrad et al found that asymptomatic non-sustained ventricular tachycardia was present in 6 of 7 patients.14 In both cohorts, no appropriate ICD therapies were observed during the follow-up period for patients with ICD implantation for primary prevention. It is therefore important to consider ICD implantation in patients with symptomatic arrhythmias. Conversely, however, in a study by Miani et al, 4 of 6 women with Danon disease died suddenly (1 aborted) at age 37–54 years;15 in another series by Maron et al, 2 of 7 patients experienced sudden unexpected ventricular fibrillation or rapid ventricular tachycardia,4 suggestive of a severe arrhythmogenic phenotype. In our study, 1 male patient suffered an aborted cardiac arrest for ventricular fibrillation and another female patient died suddenly at the age of 14 years. The difference in arrhythmogenic manifestations of Danon disease highlights the need for disease-specific risk stratification for sudden cardiac death and ICD implantation. It is noteworthy that lethal ventricular tachyarrhythmias may be unresponsive to defibrillation in patients with Danon disease.4

Our study provided details of electrophysiological characteristics in association with ventricular pre-excitation. Although FVPs are usually considered as rare variants in patients with manifested ventricular pre-excitation, cases have been frequently reported for 1.2–77% of selected populations.16,17 Our study found that the FVPs were present in all of our patients upon electrophysiological studies, suggesting that genetic defects in LAMP2 may disrupt the cardiac conduction system (Supplementary Figure 3). These FVPs in our patients were characterized by short or normal HV intervals, early local ventricular activation and discrete accessory pathway potentials at the His bundle region, and bidirectional conduction. Thus, a normal HV interval cannot exclude the possibility of an FVP in patients with Danon disease. In these patients, 2 had relatively short AH intervals, which is suggestive of accelerated AV node conduction, which could partially contribute to short PR intervals but not explain the presence of delta waves.

Additionally, our study also provided the first definite evidence for an association of WPW and Danon disease. The LAMP2 mutations not only disrupted the His-Purkinje system to result in formation of FVPs, but also affected the development of the annulus fibrosus to cause true antegrade (WPW), retrograde AV accessory pathways or both (Supplementary Figure 3). Unlike accessory pathways present in patients with a normal heart, extensive disruptions of the annulus fibrosus may occur in patients with Danon disease with resultant incredibly broad accessory pathways. The underlying mechanism for the formation of FVPs and AV accessory pathways in patients with Danon disease is not clear, but it is possibly similar to that for PRKAG2-dependent pre-excitation. Cardiac histopathology revealed that the annulus fibrosis was disrupted by glycogen-filled myocytes in transgenic mice overexpressing mutant PRKAG2.18

To the best of our knowledge, FVPs have not yet been shown to mediate arrhythmias so far, and therefore invasive electrophysiological studies for ventricular pre-excitation are unnecessary in the majority of patients with Danon disease. FVPs can be differentiated from WPW syndrome through a non-invasive maneuver. AV nodal blocking agents (calcium channel blockers, β-blockers and digoxin) could be safely used even during pre-excited atrial fibrillation in patients with Danon disease because FVPs are completely an infranodal structure. Of note, however, as presented in our series, FVPs may coexist as bystanders in association with true AV accessory pathways responsible for supraventricular tachycardia. In this scenario, AV nodal blocking agents should be avoided because accelerated AV conduction over accessory pathways could cause deterioration of atrial fibrillation into ventricular fibrillation. Catheter ablation of these AV accessory pathways may be challenging due to the extensive involvement of annulus fibrosis in Danon disease.

Previous reports about ECG features of Danon disease concentrated on conduction abnormalities, but our study further extended the phenotypic spectrum. The peculiar ECG profile in Danon disease also included wide and notched QRS complex, left ventricular high voltage, and QT interval prolongation. The high voltage is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy. A wide QRS complex cannot be completely explained by the presence of FVPs because FVPs usually create a minimal ventricular pre-excitation with normal or borderline QRS width. Manifested AV accessory pathways may cause more obvious delta waves, but occur significantly less frequently than FVPs in Danon disease. Intraventricular conduction delay might be present in these patients. The notched wide QRS has been regarded as a marker of inhomogeneous activation of the ventricles, which is related to the myocardial scar.19 The age-associated differences in the number of ECG leads with notched QRS and QRS width reveal the progressive nature of Danon disease, and therefore may have potential predictive values in identifying individuals at increased risk for cardiac death. We previously reported myofibrillar disruption in the endomyocardial tissue of patients with Danon disease,10 and speculated this ultra-structural alteration may account for abnormalities in ventricular electrical activation, including depolarization and repolarization.

Like Danon disease, mutations in PRKAG2 result in glycogen-storage cardiomyopathy, with similar pre-excitation patterns on ECG. Clinically, progressive conduction diseases that require pacemaker implantation (complete AV block or symptomatic sinus bradycardia) occur in 38% of patients with PRKAG2 cardiomyopathy at a mean age of 38 years.20 These significant ECG changes over time were also observed in patients with Danon disease. In a cohort of 27 patients with Danon disease from 10 Spanish hospitals, 50% of male patients and 29% of female patients experienced complete AV block.21 In our series, 2 patients developed AV conduction block and another had decreased AV node conduction with an effective refractory period of 440 ms. It is likely that there is a common mechanism in Danon disease and PRKAG2 cardiomyopathy responsible for the high incidence of cardiac conduction disorders.

Study LimitationsThe electrophysiological study was not performed for all subjects. The predictive value of notched QRS for myocardial scar was not defined by nuclear imaging, and the association of ECG indexes and clinical outcomes needs to be further studied. Systematic evaluation of 3 or more generations of family members was not conducted in the present study. Clinical, echocardiographic, and electrophysiological phenotypes of Danon disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy were not compared in the present study, but our previous study elucidated this issue in detail.10

The present study demonstrates a malignant clinical course characterized by rapid deterioration and early death in both male and female patients with Danon disease. Early identification and regular cardiology evaluations are critical because of the progressive nature of this disease. This study expands the phenotypic manifestations of ECG and electrophysiological abnormalities related to Danon disease and shows extensive involvement of this entity in the cardiac conduction system and annulus fibrosis. These observations indicate the pre-excited ECG pattern in Danon disease is related to FVPs with or without WPW syndrome. Further studies will be warranted to elucidate the cause and clinical effect of FVPs in patients with Danon disease.

The authors wish to thank Mr. Zhijiang Liang from Guangdong Women and Children’s Hospital for statistical consultation.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81970288 and 81770380) and the Science and Technology Programs of Guangdong Province (grant number 2019B020230004).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The Research Ethics Committee of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Reference number: No. GDREC2016339H) approved this study.

Please find supplementary file(s);

http://dx.doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-21-0572