論文ID: CJ-23-0131

論文ID: CJ-23-0131

Background: Patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) show various physical findings, but their clinical significance has not been systematically evaluated.

Methods and Results: This study evaluated 105 consecutive patients with HCM who had undergone phonocardiography and external pulse recording. Physical examinations included a visible jugular a-wave (Jug-a), audible 4th sound (S4), and double or sustained apex beat. The primary outcome was a composite of all-cause death and hospitalization for cardiovascular disease. A total of 104 non-HCM subjects served as controls. The prevalence of visible Jug-a in the seated or supine position, audible S4, and a sustained or double apex beat in patients with HCM were 10%, 71%, 70%, 42%, and 27%, respectively, all of which were significantly higher than in the controls (0%, 20%, 11%, 17%, and 2%; P<0.001 for all comparisons). The combination of visible Jug-a in the supine position and audible S4 yielded a specificity of 94% and sensitivity of 57%. During a follow-up period of 6.6 years, 6 patients died and 10 were hospitalized. The absence of audible S4 was a predictor of cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 3.91; 95% confidence interval, 1.41 to 10.8; P=0.005).

Conclusions: Detection of these findings has clinical importance in the diagnosis and risk stratification of HCM prior to the use of advanced imaging techniques.

The physical examination (i.e., inspection, auscultation, palpation, and percussion) is fundamental to all medical fields, playing an essential and important role in the diagnosis and management of heart disease for centuries. Over the past decades, however, advances in imaging technologies have resulted in the physical examination becoming a “lost art”.1 It is worth noting again that clinical practice without a physical examination may result not only in the lack of a rapport with the patient, but also in incorrect or delayed diagnoses and a considerable waste of limited medical resources, because of the significance of physical findings to the care of patients.2,3

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) patients commonly show a variety of physical findings, such as a prominent jugular venous a-wave (Jug-a), audible 4th sound (S4), and abnormal apex beat.4,5 Although these physical features appear to be highly characteristic of HCM, their prevalence and diagnostic value have not been systematically evaluated. Because the prevalence of HCM is estimated to be relatively high in the general population (i.e., 1 : 200 to 1 : 500),6,7 a stronger emphasis on the importance of diagnostic information obtained at the bedside is needed, even in the modern era of advanced imaging techniques. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to examine the clinical significance of the physical findings in patients with HCM.

This retrospective study enrolled 105 consecutive patients with HCM (82 men; mean age, 64 years) who had undergone assessments including phonocardiography and external pulse recording at Matsushita Memorial Hospital. The diagnosis of HCM was based on conventional echocardiographic demonstration of left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic thickness ≥15 mm in the absence of any cardiac or systemic disorder that may cause hypertrophy, such as severe hypertension defined as blood pressure ≥160/100 mmHg or aortic stenosis defined as an aortic valve area <1.5 cm2. Exclusion criteria were a history of atrial fibrillation, atrioventricular block, catheter ablation, permanent mechanical device implantation, or heart transplantation. Age- and sex-matched control subjects were 104 patients (74 men; mean age, 63 years) who visited the Department of Cardiology at Matsushita Memorial Hospital for various reasons and were later diagnosed with cardiac or non-cardiac diseases other than HCM (ischemic heart disease in 31 patients, valvular heart disease in 13, heart failure in 12, arrhythmias in 11). The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Matsushita Memorial Hospital and informed consent was given by all patients.

Physical FindingsThe jugular venous pulse was examined at rest with normal breathing while seated and supine. Jug-a was considered to be visible when a positive wave (i.e., rise and fall) was recognized during late diastole and just before the 1st heart sound8 (Supplementary Movie 1). S4 on auscultation was assessed in the seated, supine, and half left lateral decubitus positions. S4 was considered to be present when a low frequency sound during late diastole and before the onset of the 1st heart sound was heard best at the apex.9 The visual and palpable assessment of apex beats was performed in the supine and half left lateral decubitus positions. The apex beat was considered to be sustained if it was associated with an outward impulse lasting up to or longer than the 2nd heart sound (Supplementary Movie 2), and considered to be double if it was felt in early systole and again in late diastole10 (Supplementary Movie 3). These physical findings (i.e., visible Jug-a, audible S4, and a double or sustained apex beat) are rarely detected in healthy subjects.8,9,11,12 Other physical findings (e.g., bisferiens (spike and dome) carotid pulse or increases in murmur with appropriate provocation) were not examined in the present study because they may simply reflect the presence of a LV outflow tract obstruction.13 All examinations were assessed by a single cardiologist who was well trained in cardiac physical examinations. Data on physical examinations were available for 90 patients with HCM and all control subjects for the assessment of Jug-a in the seated position, 84 patients with HCM and all control subjects for Jug-a in the supine position, 85 patients with HCM and all control subjects for a sustained apex beat, and 83 patients with HCM and all control subjects for the double apex beat.

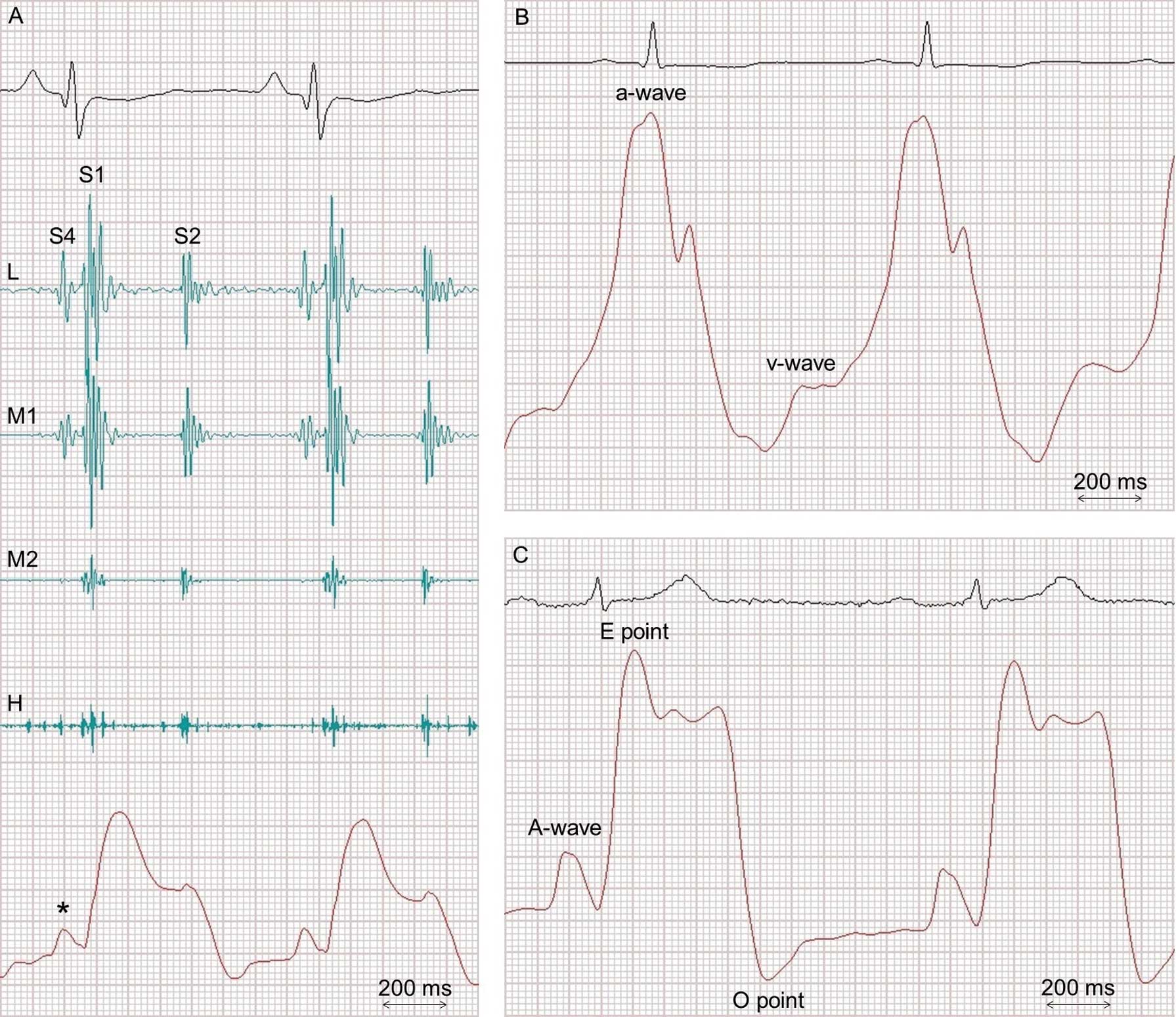

Phonocardiography and External Pulse RecordingAll patients with HCM underwent phonocardiography, jugular pulse tracing, and apexcardiography, as shown in Figure 1. A phonocardiogram was obtained at the apex as well as at the right and left sternal borders in the half left lateral decubitus position or supine position using a commercially available device (MES-1000, Fukuda-Denshi Co., Tokyo, Japan) as described previously.14,15 Measurements included 4 frequencies: low, lower-middle, higher-middle, and high. The cut-off, attenuation, nyquist, and differential sensitivity were 50 Hz, −6 dB/Oct, 1, and −32 dB, respectively, for the low frequency; 50 Hz, −18 dB/Oct, 3, and −32 dB for the lower-middle frequency; 160 Hz, −24 dB/Oct, 4, and −16 dB for the higher-middle frequency; and 315 Hz, −24 dB/Oct, 4, and 0 dB for the high frequency. When an apexcardiogram was recorded, a simultaneous apical phonocardiogram was obtained near the apex because the microphone of the apexcardiogram was placed exactly at the apex. S4 was considered to be present when a low frequency sound after the onset of the P wave on ECG and before the onset of the QRS complex was recorded best at the apex, coinciding with an A-wave on the apexcardiogram if available. S4 needed an amplitude ≥1.0 mm on the phonocardiogram with the aforementioned settings. A large Jug-a on pulse tracing was considered to be present when Jug-a was the tallest deflection exceeding the jugular v-wave by >50% of the total jugular deflection.11 A large A-wave on the apexcardiogram was considered to be present when the ratio of the apical A-wave to the total deflection (i.e., the vertical distance between the E and O points) was ≥15%.12 The presence of a high systolic plateau following the beginning of the LV ejection (i.e., the E point) was defined as the systolic plateau.12

Representative cases. Case 1: A 37-year-old woman with HCM (A). Phonocardiogram obtained near the apex shows an additional sound before the first sound (S1) at both a low frequency (L) and lower-middle frequency (M1), but not at a higher-middle frequency (M2) or high frequency (H), coinciding with an A-wave on the apexcardiogram (*), findings consistent with the 4th sound (S4). Case 2: A 48-year old man with HCM (B) showing a large a-wave, defined as the tallest deflection exceeding the v-wave by >50% of the total jugular deflection. Case 3: A 77-year-old man with HCM (C). The apexcardiogram shows a large A-wave with a ratio of the A-wave to the vertical distance between the E point and O point >15% and accompanied by a high systolic plateau following the E point (i.e., a sustained apex beat). S2, 2nd sound.

The LV end-diastolic diameter, LV ejection fraction, maximum LV wall thickness, left atrial end-systolic diameter, mitral valve E and A-wave peak velocity, and septal mitral annular early peak velocity (E’) were measured with echocardiography equipment (Vivid E9; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) using a standard method.16 An LV outflow tract obstruction was considered to be present when the peak flow velocity was >2.5 m/s by the Doppler method under resting conditions or with the Valsalva maneuver. Apical HCM was defined as ventricular hypertrophy predominantly confined to the LV apex below the papillary muscle level with a maximum wall thickness ≥13 mm in the absence of significant hypertrophy at the basal level.17 Echocardiographic data were available in all patients with HCM.

Follow-up and EndpointAll patients were followed up after the physical examination. Patient information was obtained from available medical records and interviews with the patients and/or their physicians in charge. The primary outcome was a composite of all-cause death and hospitalization for cardiovascular diseases.

Statistical AnalysisCategorical variables were compared by the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean±standard deviation and were compared using Student’s t-test. Event rates for the primary outcome were estimated with Kaplan-Meier curves and compared with a log-rank test. Cox proportional-hazards models stratified according to S4 were used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). A two-sided P<0.05 was considered significant. Cohen's kappa coefficient was used to assess interobserver agreement for the presence or absence of physical examination findings on the same day between 2 observers blinded to the results.

The prevalence of visible Jug-a in the seated or supine position, audible S4, and a sustained or double apex beat in patients with HCM were 10%, 71%, 70%, 42%, and 27%, respectively. No significant differences were observed in age, sex, family history of HCM, or premature death between patients with and without a visible Jug-a in the seated or supine position, audible S4, and a sustained or double apex beat (Table 1). The prevalence of S4 on phonocardiography was significantly higher in patients with than in those without a sustained or double apex beat, whereas no significant differences were noted in a large Jug-a on pulse tracing between the 2 groups. HCM patients with a sustained or double apex beat showed a large A-wave or systolic plateau on apexcardiography significantly more frequently than those without a sustained or double apex beat. Other physical findings (i.e., visible Jug-a in the seated or supine position and audible S4) were not associated with mechanocardiographic measurements (i.e., S4 on phonocardiography, large Jug-a, large apical A-wave, and systolic plateau). No consistent relationships were noted between physical and echocardiographic findings; however, for example, patients with a visible Jug-a while seated had a significantly smaller LV end-diastolic diameter (Table 1).

| Visible Jug-a | Audible S4 | Apex beat | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seated | Supine | Sustained | Double | |||||||

| Absent (n=81) |

Present (n=9) |

Absent (n=24) |

Present (n=60) |

Absent (n=31) |

Present (n=74) |

Absent (n=48) |

Present (n=35) |

Absent (n=61) |

Present (n=22) |

|

| Age, years | 64±12 | 67±9 | 62±12 | 65±11 | 67±12 | 64±12 | 66±12 | 62±12 | 65±12 | 62±12 |

| Male | 81% | 67% | 75% | 83% | 61% | 85% | 73% | 89% | 75% | 91% |

| Family history | ||||||||||

| HCM | 36% | 44% | 29% | 29% | 39% | 35% | 35% | 37% | 36% | 36% |

| Premature death§ | 15% | 22% | 21% | 11% | 10% | 18% | 21% | 11% | 20% | 9% |

| Mechanocardiography | ||||||||||

| S4 on phonocardiography |

80% | 56% | 75% | 80% | 68% | 84% | 69% | 91%† | 74% | 95%‡ |

| Large Jug-a | 60% | 71% | 59% | 63% | 48% | 67% | 60% | 68% | 63% | 63% |

| Large apical A-wave | 49% | 25% | 54% | 47% | 40% | 51% | 36% | 63%† | 40% | 68%‡ |

| Systolic plateau | 65% | 50% | 63% | 64% | 57% | 66% | 51% | 80%†† | 55% | 86%‡‡ |

| Echocardiography | ||||||||||

| LV end-diastolic diameter, mm |

43±5 | 39±3** | 44±5 | 43±4 | 43±6 | 44±5 | 43±5 | 44±4 | 43±5 | 43±4 |

| LV ejection fraction, % |

66±6 | 67±9 | 65±7 | 67±5 | 66±6 | 66±6 | 66±5 | 66±7 | 66±6 | 66±7 |

| Maximum LV wall thickness, mm |

19±5 | 18±5 | 20±5 | 19±5 | 19±6 | 20±6 | 20±6 | 19±5 | 20±6 | 18±5 |

| Left atrial dimension, mm |

37±6 | 35±6 | 38±5 | 36±5# | 37±5 | 37±6 | 37±5 | 37±5 | 37±5 | 36±5 |

| E, cm/s | 65±16 | 76±18 | 64±14 | 66±16 | 68±19 | 65±18 | 66±15 | 67±19 | 67±15 | 65±20 |

| A, cm/s | 70±23 | 68±28 | 68±25 | 69±22 | 81±24 | 67±21¶ | 72±23 | 66±22 | 72±24 | 60±16‡ |

| Mitral annular E’, cm/s |

5.2±1.6 | 4.4±0.9 | 5.5±1.9 | 4.9±1.4 | 4.7±1.3 | 5.0±1.7 | 5.2±1.6 | 4.9±1.5 | 5.0±1.5 | 5.1±1.7 |

| E/E’ | 13.2±4.3 | 17.8±5.3* | 12.7±4.4 | 14.0±4.8 | 15.3±5.7 | 13.8±4.9 | 13.4±4.4 | 14.5±5.1 | 13.8±4.3 | 13.9±5.8 |

| LV outflow tract obstruction |

15% | 22% | 14% | 15% | 23% | 16% | 15% | 17% | 11% | 27% |

| Apical type | 24% | 0% | 13% | 28% | 16% | 24% | 19% | 15% | 18% | 36% |

Data are mean±standard deviation or %. §Death in 1st- or 2nd-degree relative. **P<0.01, *P<0.05 vs. patients without visible Jug-a in the seated position; #P<0.05 vs. patients without visible Jug-a in the supine position; ¶P<0.01 vs. patients without audible S4; ††P<0.01, †P<0.05 vs. patients without a sustained apex beat; ‡‡P<0.01, ‡P<0.05 vs. patients without a double apex beat. HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; Jug-a, jugular a-wave; LV, left ventricular; S4, 4th heart sound.

Among the 104 control subjects without HCM, the prevalence of a visible Jug-a in the seated or supine position, audible S4, and a sustained or double apex beat were 0%, 20%, 11%, 17%, and 2%, respectively, all of which were significantly lower than in patients with HCM (P<0.001 for all comparisons). The value of physical findings for the diagnosis of HCM is summarized in Table 2. Single physical findings with a diagnostic accuracy >75% were visible Jug-a in the supine position and audible S4. The specificity and positive predictive value of visible Jug-a in the seated position were both 100%, although sensitivity was only 10%. Similarly, the presence of a double apex beat had a specificity of 98% and positive predictive value of 92% for the diagnosis of HCM, but sensitivity was still low at 27%. The coexistence of a visible Jug-a in the supine position and audible S4, which was the only combination with a diagnostic accuracy >75%, yielded higher specificity and a positive predictive value (94% and 89%, respectively), with a sensitivity of 57%.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Accuracy | PPV | NPV | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single finding | |||||||||

| Visible Jug-a seated | 10% | 100% | 58% | 100% | 56% | ||||

| Visible Jug-a supine | 71% | 80% | 76% | 74% | 78% | ||||

| Audible S4 | 70% | 89% | 80% | 87% | 75% | ||||

| Sustained apex beat | 42% | 83% | 65% | 66% | 64% | ||||

| Double apex beat | 27% | 98% | 66% | 92% | 63% | ||||

| Combination of 2 findings | |||||||||

| Visible Jug-a seated | + supine | 10% | 100% | 60% | 100% | 58% | |||

| + S4 | 6% | 100% | 56% | 100% | 55% | ||||

| + sustained | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | ||||

| + double | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | ||||

| Visible Jug-a supine | + S4 | 57% | 94% | 77% | 89% | 73% | |||

| + sustained | 31% | 95% | 67% | 83% | 64% | ||||

| + double | 19% | 99% | 64% | 94% | 61% | ||||

| Audible S4 | + sustained | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | |||

| + double | 25% | 98% | 66% | 91% | 62% | ||||

| Sustained apex beat | + double | 27% | 98% | 66% | 92% | 63% | |||

| Combination of 3 findings | |||||||||

| Visible Jug-a seated | + supine | + S4 | 10% | 100% | 70% | 100% | 69% | ||

| + supine | + sustained | 3% | 100% | 58% | 100% | 57% | |||

| + supine | + double | 3% | 100% | 58% | 100% | 57% | |||

| + S4 | + sustained | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | |||

| + S4 | + double | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | |||

| + sustained | + double | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | |||

| Visible Jug-a supine | + S4 | + sustained | 29% | 98% | 68% | 92% | 64% | ||

| + S4 | + double | 19% | 99% | 64% | 94% | 61% | |||

| + sustained | + double | 25% | 98% | 66% | 91% | 62% | |||

| Audible S4 | + sustained | + double | 25% | 98% | 66% | 91% | 62% | ||

| Combination of 4 findings | |||||||||

| Visible Jug-a seated | + supine | + S4 | + sustained | 3% | 100% | 58% | 100% | 57% | |

| + supine | + S4 | + double | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | ||

| + S4 | + sustained | + double | 3% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | ||

| Visible Jug-a supine | + S4 | + sustained | + double | 2% | 100% | 57% | 100% | 57% | |

| Combination of 5 findings | |||||||||

| Visible Jug-a seated | + supine | + S4 | + sustained | + double | 18% | 99% | 63% | 94% | 61% |

Jug-a, jugular a-wave; NPV negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

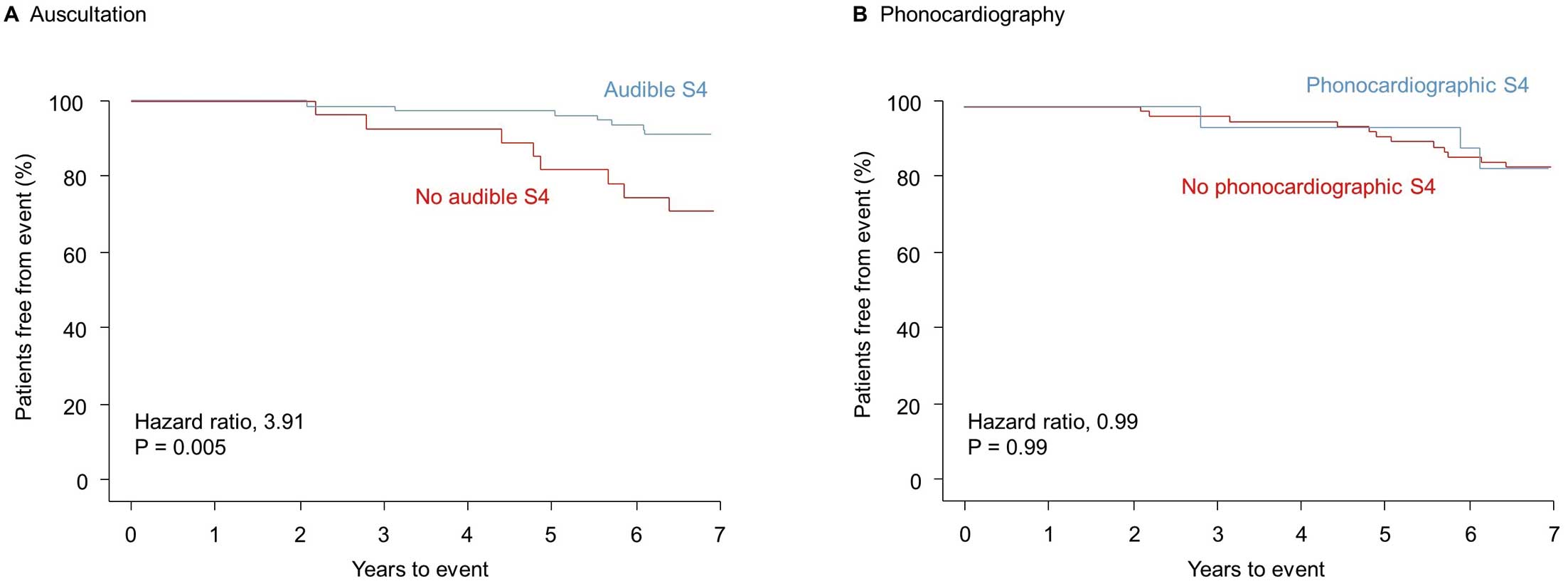

Follow-up data on outcomes in relation to the physical examination were available in 87 patients with HCM. During a follow-up period of 6.6 years (2.1–7.0), 6 patients died and 10 were hospitalized. The primary outcome was associated with an audible S4 (P<0.01) but not with a visible Jug-a in the supine position (P=0.46), visible Jug-a in the seated (P=0.59), sustained apex beat (P=0.90), or double apex beat (P=0.49) in patients with HCM. The absence of an audible S4 was a predictor of poor outcome (HR, 3.91; 95% CI, 1.41–10.8; P=0.005), although there were no significant differences in the phonocardiographic S4 (P=0.99) between patients with and without cardiovascular events with no predictive value (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.28 to 3.52; P=0.99) (Figure 2).

Kaplan-Meier curves are shown for the primary outcome according to the presence or absence of the 4th sound (S4) as assessed by auscultation (A) and phonocardiography (B). The primary outcome was a composite of all-cause death and hospitalization for cardiovascular diseases.

The reproducibility of physical examination findings was evaluated in a total of 12 patients with HCM and 8 controls. Interobserver agreement was obtained for 10 positive and 8 negative findings; disagreement was observed in 2 HCM patients each for the presence or absence of a visible Jug-a in the supine position and an audible S4. The Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated to be 0.80 (excellent agreement). The diagnostic values of the 2 observers for HCM based on the coexistence of a visible Jug-a in the supine position and an audible S4 were specificity of 100% and 89%, sensitivity of 58% and 63%, and accuracy of 75% and 75%, respectively.

The present study was conducted to examine the prevalence of various physical findings in patients with HCM and control subjects, and assess the contribution of these physical findings to the diagnosis. The results obtained showed that a visible Jug-a, audible S4, and a sustained or double apex beat were characteristic of HCM. The presence of a visible Jug-a in the supine position or an audible S4 was sensitive for the diagnosis of HCM, whereas specificity was excellent for a visible Jug-a in the seated position, followed by a double apex beat. The combination of a visible Jug-a in the supine position and an audible S4 balanced well with good specificity and acceptable sensitivity. The absence of an audible S4 was associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events.

The main result of the present study was the diagnostic usefulness of a physical examination of patients with HCM, including visible Jug-a, audible S4, and a double apex beat. S4 is commonly heard in HCM patients with a sinus rhythm.15,18 A double apex beat has also been recognized for more than half a century as a physical sign in patients with HCM,19 in addition to a prominent Jug-a.20 The underlying mechanisms have not yet been elucidated in detail; however, one physiological condition in patients with HCM may play a primary role in these 3 phenomena: a forceful left atrial contraction into a non-compliant LV. An echocardiographic examination using tissue Doppler imaging and a 2D strain study showed that left atrial longitudinal strain was less in HCM patients than in non-HCM patients with LV hypertrophy or healthy subjects.21 Hemodynamic stress to the atrium may explain why patients with HCM more frequently develop atrial fibrillation than the general population, and also why the presence of atrial fibrillation is closely associated with an impaired quality of life and poor prognosis in this clinical setting.22

It is reasonable to assume that the LV is the main source of an audible S4 or a double apex beat, with some exceptions. However, based on the connection between the jugular vein and right atrium, the role of right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy in a visible Jug-a may need to be considered. The presence or absence of RV hypertrophy was not reliably assessed in the present study (e.g., based on cardiac magnetic resonance); however, a large cohort of >2,000 patients with HCM showed that the prevalence of RV hypertrophy was only 1.3% when it was defined as a maximum RV wall thickness ≥10 mm.23 It is also important to note that LV hypertrophy may influence RV properties through the interventricular septum, known as the “Bernheim effect”.24 This ventricular interdependence was previously reported to be notable during diastole in a pressure-volume analysis of animal models.25

Discordance between the physical findings and mechanocardiographic measurements was noted in the present study. For example, a large apical A-wave on the apexcardiogram was not observed in approximately one-third of the patients with HCM who showed a double apex beat. However, this was not unexpected, because a large A-wave on an apexcardiogram may be impalpable in some patients due in part to the geometry of the body as well as the LV. In 200 consecutive subjects who underwent multislice cardiac computed tomography, the presence of a palpable apical impulse correlated with the LV mass index, the distance from the heart to the chest wall, and male sex.26 These factors may explain the present result of the presence of a phonocardiographic S4 in approximately two-thirds of HCM patients without an audible S4. S4 can be difficult to clearly separate from the 1st heart sound by auscultation, but not by phonocardiography.27

The mechanism between the absence of an audible S4 and adverse events remains to be elucidated. A gradual decline in atrial function may contribute to the loss of the ability to produce S4, even in HCM patients in sinus rhythm. It is not surprising that HCM patients with impaired atrial function are more likely to develop cardiovascular events, even while still in sinus rhythm on ECG. In our previous report on patients with HCM in sinus rhythm, the absence of S4 on phonocardiography was significantly associated with exercise intolerance, as assessed by a cardiopulmonary exercise test, as well as newly developed atrial fibrillation.28 On the other hand, in the present study, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of S4 as assessed by phonocardiography between patients with and without cardiovascular events. Methodological uncertainties remain, but phonocardiography may be oversensitive in detecting S4, leading to underestimation in the assessment of atrial dysfunction. Further research is warranted to confirm details of the underlying physiology.

Study LimitationsThe present study was conducted at a single center with selected patients, implying that the results obtained cannot be extrapolated to the general HCM population. Furthermore, a physical examination may have inherent inaccuracies and findings may wax and wane, because hemodynamics dynamically change in patients with HCM. In addition, the prevalence and diagnostic value of 3 physical findings (i.e., Jug-a, S4, and apex beat) were examined in the present study, but other findings may be informative for the diagnosis of HCM, such as a more shallow y-descent of the jugular venous pulse, although this shows considerable overlap with normal subjects.29 Another limitation is the variations in the etiologies of the diseases of the control subjects, aside from not being diagnosed with HCM. This diversity may have biased the results; however, most patients who are referred to cardiology departments have various conditions.

In conclusion, patients with HCM have distinct and characteristic physical findings, such as a visible Jug-a, audible S4, and a double apex beat, and more effort should be made to detect these before the use of advanced imaging techniques.

The authors thank Drs. Hiroki Sugihara and Haruhiko Adachi for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Design of the work: T.K. Data acquisition: T.K. Data analysis and interpretation: T.K. Drafting the work: T.K. Constructive and critical review: H.S., S.M. Final approval: all.

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Matsushita Memorial Hospital (No. 19037).

Supplementary Movie 1. Jugular venous pulsation. Note the positive wave (i.e., rise) or prominent jugular a-wave in the supine position.

Supplementary Movie 2. Apex beat. Note the outward impulse or sustained apex beat in the half left lateral decubitus position.

Supplementary Movie 3. Apex beat. Note the double apex beat, as shown by the movement of the yellow sticky note attached to the apex in the half left lateral decubitus position.

Please find supplementary file(s);

https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-23-0131